Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cirugía

Print version ISSN 2250-639XOn-line version ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.114 no.3 Cap. Fed. Sept. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v114.n3.1602

Articles

Laparoscopic approach to abdominal trauma. Experience in a trauma hospital

1 Servicio de Cirugía General del Hospital de Emergencias Dr. Clemente Álvarez (HECA). Rosario, Santa Fe. Argentina.

Introduction

Trauma is a global health issue and the leading cause of death in young people. Historically, laparotomy has been the approach used for patients with abdominal trauma. Based on this criterion, many negative laparotomies (when there is absence of peritoneal injury) and non-therapeutic laparotomies (in cases of peritoneal injury and certain intra-abdominal injuries that do not require treatment) are performed1.

These laparotomies are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, which may be 5% and 20%, respectively, according to some published series2. The most common complications are surgical site infection, evisceration, postoperative ileus, aspiration pneumonia, hospital-acquired pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis and incisional hernia in the long-term follow-up3. Another aspect to consider is that a negative exploratory laparotomy entails longer hospital stay, resulting in longer time until the patients reintegrate into their communities and return to work. Different strategies have been proposed to evaluate penetrating wounds to improve morbidity and mortality rates, such as local wound exploration4,5, computed tomography (CT) scan6 and patient monitoring with serial examinations. Laparoscopy is another accepted approach for hemodynamically stable patients (systolic blood pressure > 90 mm Hg) and for those with open abdominal injuries7,8.

In general, laparoscopy has demonstrated many advantages over open surgery, as less postoperative pain, shorter length of hospital stay, less postoperative ileus, better cosmetic results, faster recovery and earlier return to work9.

The initial publications reported that one of the main disadvantages of laparoscopy in trauma surgery was the possibility of missed injuries10. The incidence of this complication has decreased over the past years due to improvements in the understanding of laparoscopy and its instruments. Generally, these missed injuries were found in the liver, posterior wall of the stomach, duodenum, small intestine, bladder, splenic flexure and mesenteric border of the colon. Laparoscopy has screening, diagnostic and therapeutic roles. Screening laparoscopy detects if the stab wound or gunshot injury penetrates into the peritoneum. Diagnostic laparoscopy identifies all the intra-abdominal injuries in addition to what has been previously described11. A systematic examination of the cavity should be performed including all the quadrants of the abdomen12,13. It has excellent sensitivity in determining the need for therapeutic laparotomy and can help us choose the site of such incision. The conversion rate described in the international bibliography ranges between 20 and 40%14-16.

Finally, in therapeutic laparoscopy the injuries are repaired without need for laparotomy17. The diaphragm is the organ most commonly repaired during therapeutic laparoscopies18, followed by the small bowel, generally with single injuries19,20.

Video-assisted laparoscopy is indicated in patients who are hemodynamically stable and when there are no indications for exploratory laparotomy (hemodynamic instability, diffuse peritonitis or evisceration)21. Intracranial injuries, high-grade chest trauma and pregnancy are limitations for laparoscopy. The possible complications of the method include physiologic changes due to pneumoperitoneum, access-related complications, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothroax, gas embolism, injuries to the diaphragm, blood vessels, omentum, bowel, and urinary bladder, and port site incisional hernias28. The rate of complications is decreasing due to constant improvement of materials and equipment and to the learning curve of the professionals. The aim of this study is to describe our experience in diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy in trauma for 4 years and evaluate its usefulness.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective review of the medical records and operative protocols of hemodynamically stable patients admitted with open abdominal trauma from January 2016 to January 2020 who underwent laparoscopic surgery. The following items were evaluated in these patients: Type of open trauma (gunshot injury or stab wound)

▪ Examination of the wound

▪ CT scan before surgery

▪ Diagnostic or therapeutic procedure

▪ Intraoperative findings

▪ Conversion rate

▪ Laparotomy size

▪ Operative time

▪ Postoperative complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification

▪ Length of hospital stay

Procedure

The procedures were performed under general anesthesia with the patient placed in the supine position. Shoulder pads were placed under the thighs fixed to the surgical table so that the patient could be mobilized and all the quadrants of the abdomen could be explored. In all the patients the camera was introduced at the umbilical level and at least two working trocars were inserted in both lumbar regions, as shown in Figure 1. Occasionally, the trocars were placed in other sites according to site of the primary injury. In some patients the stab wounds were used to insert the trocars.

The hemoperitoneum or intestinal fluid were aspirated. A systematic examination of the cavity was performed, starting in the right hypochondriac region and continuing in a clockwise direction. Two atraumatic graspers were used to examine the small bowel from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve. The lesser sac was systematically explored to rule out injuries of the duodenum, pancreas and posterior surface of the stomach. The colon was completely mobilized when it was in the projection of the injury. The surgical interventions continued according to the findings. The ports and wounds were closed in planes.

Results

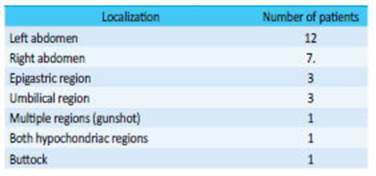

During a 4-year period (from January 2016 to January 2020), 540 patients were operated on in our department due to open abdominal trauma; 28 patients (5.2%) were approached by video-assisted laparoscopy. Twenty-seven (96%) patients were men; median age was 27 years (range: 15-66). Seventeen (60%) patients were admitted due to stab wound and 11 patients had gunshot injuries. The sites of injury are described in Table 1.

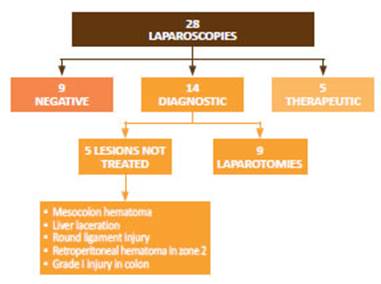

Two patients were admitted with evisceration of the small bowel through the stab wound. During physical examination, the stab wounds were examined under local anesthesia in 10 patients with injury to the aponeurosis. Nevertheless, on video-assisted laparoscopy only 7 of them presented penetrating abdominal wounds. If laparoscopy had not been performed, these patients would have undergone unnecessary exploratory laparotomies. A CT scan was ordered to 16 patients on admission. Eleven scans reported penetrating abdominal wounds. Of these 11 patients, penetrating abdominal wounds were confirmed in 9. Therefore, 2 unnecessary exploratory laparotomies were avoided. The procedures performed are shown in figure 2.

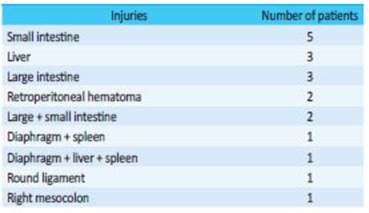

Of the 28 cases, laparoscopies were negative in 9 patients in whom the parietal peritoneum was intact. In the remaining patients, 14 were diagnostic laparotomies and 5 were therapeutic. In the diagnostic laparotomies, 5 demonstrated injuries that did not require treatment, as in the round ligament or right mesocolon without active bleeding. In the remaining cases, the characteristics of the injury diagnosed by laparoscopy required conversion to laparotomy to repair it. The conversion rate was 32% (9 patients), reducing the length of the laparotomy incision (between 4 and 8 cm) which was performed in a site of the abdomen according to the injuries found during laparoscopy. Only one patient required supraumbilical and infraumbilical laparotomy (inferior vena cava injury). Considering patients with negative laparoscopies (those with injuries that did not require treatment) and those with therapeutic laparoscopies, 68% of the patients (19) were completely approached through laparoscopy and avoided the traditional xyphopubic laparotomy used in trauma cases. The injuries found are detailed in Table 2.

During therapeutic laparoscopies the following procedures were performed:

▪ Suture of diaphragm

▪ Suture of gastric injury

▪ Hepatic hemostasis

▪ Double-barrel colostomy in injuries of the extraperitoneal rectum and anal canal.

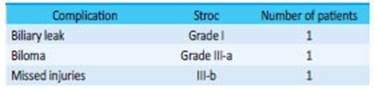

Two patients were admitted with evisceration of the small intestine that was explored through the wound, and the rest of the bowel was examined through video-assisted laparoscopy. One of them had only injury to the transverse colon that was sutured through the stab wound (thus avoiding laparotomy) and the other presented a retroperitoneal hematoma in zone 1 which required immediate laparotomy. Operative time ranged from 1 to 3 hours in the case that required laparotomy with suture of the vena cava and of multiple small intestine injuries. Among the postoperative complications (Table 3), there was one case of missed injury to the right colon in a patient admitted with a stab wound in the right lumbar region, which required reoperation (STROC grade III-b).

In addition, two patients with liver lacerations presented bile leak. In one case a drain was placed in the cavity for bile leak drainage which solved spontaneously without requiring endoscopic papillotomy or other treatment (STROC grade I). In the other patient a biloma developed requiring only percutaneous drainage (STROC grade III-a). There were no deaths in our series. Median length of hospital stay was 4 days (range 1-20 days).

Discussion

Laparoscopy provides rapid recovery with less postoperative pain and, therefore, shorter length of hospital stay. Other advantages that have also been reported include lower rate of surgical site infection, complications of the abdominal wall and postoperative ileus 9. This approach should only be used in hemodynamically stable patients. Organ evisceration in penetrating abdominal trauma is a sign of peritoneal injury and entails high risk of intra-abdominal injury (65-85%)22. Eviscerations are more common in stab wounds, and the organs involved are usually the small intestine and the omentum. Historically, these patients had indication for emergency laparotomy and laparoscopy was absolutely contraindicated. In recent years, there have been case reports of diagnostic laparoscopy, even with eviscerations through the traumatic wounds. In this way, it is possible to diagnose injuries, repair them and avoid non-therapeutic exploratory laparotomies in patients without intra-abdominal injuries23. This approach is performed when, despite negative results with CT scan or ultrasound during the secondary evaluation, injuries that may not be easily detected by these methods are suspected.

Diaphragmatic injuries are an example of this situation, as they can be obvious (as in the case of a chest X-ray showing herniation of abdominal contents in a hemithorax, mostly on the left) or subtle, difficult to be diagnosed by CT scan24. The late diagnosis of these injuries is associated with a higher risk of complications, herniation and strangulation of abdominal organs in the hemithorax. Therefore, in patients with suspected diaphragmatic injury (due to the mechanism of injury and the associated injuries) that is not documented by imaging tests, diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed. Abdominal injury may be caused by blunt trauma or penetrating trauma and should be suspected in wounds penetrating from the thorax to the abdomen or vice versa, and in case of thoracoabdominal wounds between thoracic vertebral bodies 4 and 1225,26. The most common associated injuries are in the liver, hemothorax or pneumothorax, spleen, rib fracture, small bowel, kidney, stomach, etc. If the injury is found, it can be repaired by laparoscopy or open surgery, depending on the patient’s condition, the associated injuries and the surgeon’s experience. Repair of diaphragmatic injuries should include placement of a chest tube in case of hemodynamic impairment due to a large pneumothorax. The remaining cases can be repaired and drained with a catheter27.

Another situation in which laparoscopy offers considerable benefit is when the CT scan shows free fluid without solid organ injury or pneumoperitoneum. This may be a mesentery or hollow viscera injury, both with indication for immediate surgical repair. Although blunt abdominal trauma can also be approached by laparoscopy, these patients usually have multiple traumas and associated injuries, and for this reason laparotomy is preferred. Moreover, these patients are often admitted with hemodynamic instability or traumatic brain injury, which rule out the possibility of laparoscopic approach29,30.

Several authors described a shorter length of hospital stay with exploratory laparoscopy. The ability to rule out peritoneal penetration is sufficient to discharge patients who would otherwise remain under observation31,32. Another benefit of diagnostic laparoscopy is that it reduces the size of the incision in cases where a laparotomy is mandatory to treat the lesions found33. In addition, hospital length of stay is shorter for patients who undergo therapeutic laparoscopy. This is consistent with non-trauma general surgery, where laparoscopic procedures result in fewer days of hospitalization, rapid return to work and less postoperative pain9.

Despite laparotomy is considered the preferred approach for patients with abdominal trauma worldwide, postoperative complications as wound infections, postoperative ileus and incisional hernias are greater when the size of the abdominal wall incision is large. This finding is consistent with that of other non-traumatic conditions, like appendectomies and cholecystectomies. Postoperative ileus is also more common with laparotomies, resulting in a longer hospital stay32. Examination of stab wounds as part of the physical examination and CT scans lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity. We have shown in our series that there are patients with positive explorations and CT scans who did not present penetrating abdominal injuries4,6. A concern that still exists among trauma surgeons is the operative time in the case of laparoscopy34 which depends on the injuries found and the skills of the treating surgeon. The decision of conversion should be made soon after the initial exploration. Major vascular injuries, large retroperitoneal hematomas, clinical impairment, or very large or multiple injuries that are not suitable for laparoscopic repair should force the surgeon to quickly convert to an open exploration. A systematic examination of the cavity is necessary to avoid missing any injury33, in addition to training programs focused on the laparoscopic approach to trauma, with the aim of training surgeons in advanced video-assisted laparoscopic techniques to diagnose any intra-abdominal injury and indicate the appropriate therapy35.

Single lesions can be repaired with intracorporeal suture. In case of multiple injuries, the organs are exteriorized via a 4-8 cm laparotomy incision. The incision can also be made over the primary wound, depending on its location. Finally, the entire work team (anesthesiologists, operating room staff, etc.) and the managers of the institution should understand that laparoscopy should be performed on trauma patients with the characteristics described above so that the appropriate equipment and instruments are available 24 hours a day. The retrospective and descriptive nature is one limitation of this study. Further prospective studies including the group of patients admitted for blunt trauma are needed36. The greatest benefits demonstrated were the lower number of laparotomies performed, the shorter size of the laparotomy incision in cases of conversion and, thus, the reduction in the rate of surgical site complications and shorter length of hospital stay37.

Acknowledgments:

Scientific advisor: Dr. Daniel Ludi, FACS - Associated Clinical Professor of Surgery, University of California Riverside. Assistant Professor of Surgery, Loma Linda University

REFERENCES

1. Renz BM, Feliciano DV. Unnecessary laparotomies for trauma: a prospective study of morbidity. J Trauma. 1995;38(3):350-6. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7897713. [ Links ]

2. O’Malley E, Boyle E, O’Callaghan A, Calvin Coffey J, Stewart R, Walsh SR. Role of Laparoscopy in Penetrating Abdominal Trauma: A Systematic Review. World J Surg. 2013;37:113-22. DOI 10.1007/s00268-012-1790-y. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23052797. [ Links ]

3. Weigelt JA, Kingman RG. Complications of negative laparotomy for trauma. Am J Surg. 1988;156:544-7. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3202270. [ Links ]

4. Cothren CC, Moore EE, Warren FA, Kashuk JL, Biffl WL, Johnson JL. Local wound exploration remains a valuable triage tool for the evaluation of anterior abdominal stab wounds. Am J Surg. 2009;198:223-6. Disponible en: https://www.americanjournalofsurgery.com/article/S0002-9610(08)00902-1/fulltext. [ Links ]

5. Leppaniemi A, Haapianiem R. Diagnostic laparoscopy in abdominal stab wounds: a prospective, randomized study. J Trauma. 2003;55:636-45. Disponoble en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14566116. [ Links ]

6. Morrison JJ, Clasper JC, Gibb I, Midwinter M. Management of penetrating abdominal trauma in the conflict environment: the role of computed tomography scanning. World J Surg. 2011;35(1):27-33. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0782-z. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20845038. [ Links ]

7. Sosa JL, Arrillaga A, Puente I, Sleeman D, Ginzberg E, Martin L. Laparoscopy in 121 consecutive patients with abdominal gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 1995;39(3):501-6. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7473915. [ Links ]

8. Lin HF, Wu JM, Tu CC, Chen HA, Shih HC. Value of diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for abdominal stab wounds. World J Surg. 2010;34:1653-62. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20165846. [ Links ]

9. Tiwari MM, Reynoso JF, High R, Tsang AW, Oleynikov D. Safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of common laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1127-35. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20927546. [ Links ]

10. Chelly MR, Major K, Spivak J, Hui T, Hiatt JR, Margulies DR. The value of laparoscopy in management of abdominal trauma. Am Surg. 2003; 69:957-60. Disponible en: http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/14627255. [ Links ]

11. Gazzaniga AB, Stanton WW, Bartlett RH. Laparoscopy in the diagnosis of blunt and penetrating injuries in the abdomen. Am J Surg. 1974;131:315Y31-8. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/130806. [ Links ]

12. Kawahara NT, Alster C, Fujimura I, Poggetti RS, Birolini D. Standard examination system for laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2009;67:589-95. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19741405. [ Links ]

13. Gorecki PR, Cottam D, Angus LDG, Shaftan GW. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for trauma: a technique for safe and systematic exploration. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2002;12(3):195-8. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12080264. [ Links ]

14. Chestovich PJ, Browder TD, Morrissey S L, Fraser DR, Ingalls NK, Fildes JJ. Minimally invasive is maximally effective: Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for penetrating abdominal injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015; 78 (6): 1076-85. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000655 Disponible en: https://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Abstract/2015/06000/ [ Links ]

15. Sumislawski JJ, Zarzaur BL, Paulus EM, Sharpe JP, Savage SA, Nawaf CB, et al. Diagnostic laparoscopy after anterior abdominal stab wounds: worth another look? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75: 1013-8. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24256675. [ Links ]

16. Khubutiya MSh, Yartsev PA, Guliaev AA, Levitsky VD, Tlibekova MA. Laparoscopy in blunt and penetrating abdominal injuries. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:507-12. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24300927. [ Links ]

17. Choi YB, Lim KS. Therapeutic laparoscopy for abdominal trauma. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:421-7. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12457215. [ Links ]

18. Simon RJ, Rabin J, Kuhls D. Impact of increased use of laparoscopy on negative laparotomy rates after penetrating trauma. J Trauma. 2002;53: 297-302. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12169937. [ Links ]

19. Zafar SN, Onwugbufor MT, Hughes K, Greene WR, Cornwell EE 3rd, Fullum TM, Tran DD. Laparoscopic surgery for trauma: the realm of therapeutic management. Am J Surg. 2015;209(4):627-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.12.011. Epub 2015 Jan 14. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25665928. [ Links ]

20. Barzana DC, Kotwall CA, Clancy TV, Hope WW. Use of laparoscopy in trauma at a level II trauma center. JSLS. 2011;15:179-81. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3148867/ [ Links ]

21. Zantut LF, Ivatury RR, Smith RS, Kawahara NT, Porter JM, Fry WR, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for penetrating abdominal trauma: a multicenter experience. J Trauma. 1997;42(5):825-31. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9191663. [ Links ]

22. Como JJ, Bokhari F, Chiu WC, Duane TM, Holevar MR, Tandoh MA, et al. Practice Management Guidelines for Selective Nonoperative Management of Penetrating Abdominal Trauma. J Trauma. 2010; 68(3). Disponible en: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/43a0/b1d5543310b81751ab8cb3370989773165f0.pdf [ Links ]

23. Matsevych OY, Koto M Z, Motilall SR, Kumar N. The role of laparoscopy in management of stable patients with penetrating abdominal trauma and organ evisceration. J Trauma. 2016; 81(Issue 2): 307-11 doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001064 Disponible en: https://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Abstract/2016/08000/ [ Links ]

24. Williams M, M Bulger EM, Collins KA. Recognition and management of diaphragmatic injury in adults. Upto Date May 12, 2017. Disponible en: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/recognition-and-management-of-diaphragmatic-injury-in-adults [ Links ]

25. Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Stahl WM. A critical evaluation of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1993;34(6):8228. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8315677. [ Links ]

26. Guth AA, corresponding author, Pachter HL. Laparoscopy for Penetrating Thoracoabdominal Trauma: Pitfalls and Promises. JSLS. 1998; 2(2):123-7. PMCID: PMC3015287. PMID: 9876725 Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3015287/ [ Links ]

27. Matthews BD, Bui H, Harold KL, Kercher KW, Adrales G, Park A, et al. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic injuries. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:254-8. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12399834. [ Links ]

28. Kindel T, Latchana N, Swaroop M, Chaudhry UI, Noria SF, Rachel L Choron RL, et al. Laparoscopy in trauma: An overview of complications and related topic. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2015; 5(3):196-205. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4613419/ [ Links ]

29. Justin V, Fingerhut A, Uranues S. Laparoscopy in blunt abdominal trauma: for whom? When? And Why? Curr Trauma Rep. 2017; 3:43-50. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5477632. [ Links ]

30. Heng-Fu Lin, Ying-Da Chen, Shyr-Chyr Chen. Value of diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy for patients with blunt abdominal trauma: A 10-year medical center experience. Disponible en: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193379. [ Links ]

31. Uranues S, Popa DE, Diaconescu B, Schrittwieser R. Laparoscopy in Penetrating Abdominal Trauma. World J Surg 2014;39(6):1381- 8. DOI 10.1007/s00268-014-2904-5. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25446491 [ Links ]

32. Yueli Li, Ying Xiang, Na Wu, Long Wu, Zubin Yu, Mengxuan Zhang, Minghao Wang, Jun Jiang, Yafei Li. A Comparison of Laparoscopy and Laparotomy for the Management of Abdominal Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2015;39:2862- 71. DOI 10.1007/s00268-015-3212-4. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26316111. [ Links ]

33. Koto MZ, Oleh Y, Matsevych OY, Aldous C. Laparoscopic-Assisted Approach for Penetrating Abdominal Trauma: An Underutilized Technique. J Laparoendosc Adv S. 2016; 00(00). Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27858523. [ Links ]

34. Kyoung Hoon Lim, Bong Soo Chung, Jong Yeol Kim, Sung Soo Kim. Laparoscopic surgery in abdominal trauma: a single center review of a 7-year experience. Lim et al. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:16. DOI 10.1186/s13017-015-0007-8. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26056529 [ Links ]

35. Livingston DH, Tortella BJ, Blackwood J, Machiedo GW, Rush BF. The role of laparoscopy in abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1992;33(3):471-5. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3516935/ [ Links ]

36. Fabian TC, Croce MA, Stewart RM, Pritchard FE, Minard G, Kudsk KA. A prospective analysis of diagnostic laparoscopy in trauma. Ann Surg. 1993;217(5):557-65. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1242845/pdf/annsurg00075-0163.pdf. [ Links ]

37. Miles EJ, Dunn E, Howard D, Mangram A. The role of laparoscopy in penetrating abdominal trauma. JSLS. 2004;8:304-9. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3016820/ [ Links ]

Received: March 26, 2022; Accepted: April 25, 2022

text in

text in