Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cirugía

Print version ISSN 2250-639XOn-line version ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.114 no.3 Cap. Fed. Sept. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v114.n3.1620

Articles

Stoma reversal after the Hartmann’s procedure

1 ARCO, Centro Integral de Coloproctología. Mendoza. Argentina.

Introduction

Stoma reversal after Hartman’s operation is usually a complex procedure and is associated high morbidity; therefore, many patients do not reach this stage. As the literature on this topic is not definitive on many of its aspects, we performed a retrospective review to analyze the rate of reversal of Hartmann’s operation and the postoperative results in our experience.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective review of our database between January 2004 and December 2020.

Inclusion criteria

We included patients undergoing stoma reversal after Hartman’s procedure. Variables analyzed: number of Hartmann’s operations performed in the same period and reasons for the Hartmann’s operation considering the type of disease (benign conditions or cancer) and the setting (emergency or elective procedure).

Other factors considered: percentage of patients eligible for reversal, time to reversal, and reasons not to proceed with reversal. Age, sex and preoperative risk of the ASA physical status classification.

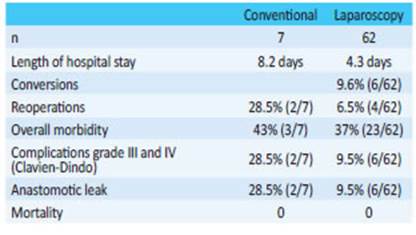

Overall morbidity and adjusted for complications grade III and IV of the Clavien-Dindo classification. Morbidity according to preoperative risk, baseline disease, setting in which the Hartmann’s operation was performed, time to reversal (before and after 1 year-per semester) and cumulative experience over time (considering only intraoperative and postoperative morbidity). Type of approach (conventional or laparoscopic), length of hospital stay, percentage of reoperations, percentage of anastomotic leak and overall mortality at 30 days following surgery. Use of diverting ostomies, categorized into 2 types: 1) protective stomas (corresponds to ostomies performed during reversal when there is high risk of anastomotic leakage) and 2) therapeutic stomas (corresponds to ostomies performed after reversal due to anastomotic leakage). Finally, the percentage of permanent ostomies was determined. Indication for reversal: special evaluation in very elderly patients or those high preoperative risk or with a history of radiation therapy. We explained to the patient the possibility of constructing a temporary ileostomy to prevent serious complications.

Timing for reversal: when the patient’s clinical and nutritional status were adequate. Preoperative assessment: preoperative risk, nutritional status, and colonoscopy. Imaging tests, if required. Preparation: we always indicate oral antibiotic prophylaxis for the colon and one enema. Mechanical bowel preparation was left to the discretion of the treating surgeon. Type of approach: we prefer the laparoscopic approach. We consider the conventional approach in patients with large midline incisional hernias requiring repair. Parostomal incisional hernias are not a contraindication for laparoscopy.

Surgical steps: 2 defined stages: 1) the stoma is mobilized and prepared for anastomosis, 2) the adhesions are freed, the pelvis is exposed, the rectal stump is identified, the splenic flexure is adequately mobilized, and the colon is lowered without tension. The treating surgeon decides whether to start with one stage or the other.

Use of diverting ostomies, categorized into 2 types: 1) protective stomas (we leave a loop ileostomy when there is high risk of anastomotic leakage) and 2) therapeutic stomas (we try to solve the anastomotic leakage with a derivative ileostomy instead of undoing the anastomosis and redoing the iliac colostomy).

Results

Over a 16-year period, we performed 92 Hartmann’s operations; 58% due to malignancies (n = 40), and 42% due to benign conditions (n = 29). Fiftytwo percent (n = 36) were elective procedures and 48% (n = 33) were urgent operations. Only 69 patients (75%) underwent reversal and mean time to reversal was 9 months (range 2 to 48).

Among the reasons why the remaining 23 patients did not undergo reversal, 18 patients had advanced cancer (7 of them died during the first postoperative year), 2 refused to proceed with reversal, 2 were elder patients, and 1 patient had psychiatric disorders. Mean age of patients undergoing reversal was 58 years (range 17 to 95); 52% were men and the distribution of preoperative risk was as follows: ASA grade 1, 36% (22); ASA grade 2, 59% (41); and ASA grade 3 9% (6). Overall morbidity was 38%. Twenty-eight complications were recorded in 26 patients: 7 surgical site infections, 6 hypertensive crises, 4 anastomotic leaks, 4 colocutaneous fistulas, 2 intraoperative bladder injuries, 2 anastomotic strictures, 1 enterocutaneous fistula, 1 bowel obstruction due to adhesions, and 1 cardiac arrhythmia.

After adjustment for complications grade III and IV of the Clavien-Dindo classification, morbidity decreased to 11.5%. These complications included 4 anastomotic leaks, 2 anastomotic strictures, 1 bowel obstruction and 1 enterocutaneous fistula. Surgical complications were managed as follows: Drainage under local anesthesia, wound care, and healing by secondary intention of the 7 surgical site infections. The 4 patients with anastomotic leak were reoperated and a therapeutic ileostomy was left. The 4 colocutaneous fistulas evidenced by discharge of fecal material through the drain with no other symptoms solved spontaneously. The 2 bladder injuries were sutured during surgery. Endoscopy-assisted balloon dilation was used to manage both anastomotic strictures. Bowel obstruction was managed by laparoscopic enterolysis. The enterocutaneous fistula, evidenced postoperatively by the drainage of enteric fluid, was managed with surgical repair.

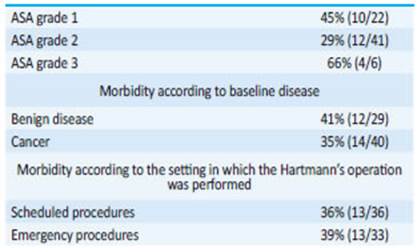

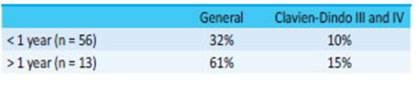

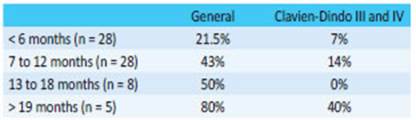

There were no significant differences in morbidity according to preoperative risk, baseline disease and setting in which the Hartmann’s operation was performed (Table 1). But when we analyzed the association between morbidity rate and time to reversal, we found lower rates when reversal was performed within the first year (Table 2) and even lower when it occurred within the first six months (Table 3).

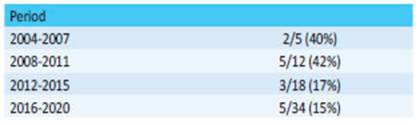

Finally, when we analyzed morbidity across the history of our department (Table 4), considering intraoperative morbidity, postoperative morbidity adjusted for complications grade III and IV of the Clavien-Dindo classification, and the 4 colocutaneous fistulas that solved spontaneously, we observed a progressive and sustained decrease over the years, which fell below 20% after 9 years of experience.

The rate of reoperations was 8.6% (6/69) and that of anastomotic leaks was 11.5% (8/69). None of the patients died. The approaches used for reversal were laparoscopy in 90% (n = 62) of the and conventional surgery in 10% (n = 7), with a mean length of hospital stay of 4.7 days (range 3 to 26 days). Table 5 shows the 2 groups and -although they are not comparable- some variables such as length of hospital stay, percentage of reoperations, overall morbidity and morbidity adjusted for complications grade III and IV (Clavien-Dindo) and anastomotic leak are lower in the laparoscopic approach. We found 19% (n = 13) of diverting protective ileostomies. These patients did not develop anastomotic leak and 11 of them underwent ileostomy closure within a mean time of 4 months. Four patients reoperated on for anastomotic leak received therapeutic ileostomy. Mean time to ileostomy closure was 15 months in all of them.

The rate of permanent stomas was 27% (n = 25) and is made up of the 23 patients who did not undergo reversal plus 2 patients with protective ileostomy that was not closed.

Discussion

The percentage of patients undergoing reversal after Hartmann’s procedure ranges between 19 to 74%1-3. Anastomotic leakage, advanced tumor category, use of neoadjuvant therapy and blood loss greater than 300 ml are associated with a risk of delay in stoma reversal2. Two prospective multicenter studies4,5 also pointed out other factors as comorbidities, impaired anorectal function, postoperative complications and secondary constructed stomas. In addition, about 18 to 30% of patients decline reversal3.

The percentage of patients reported as unsuitable for reversal due to advanced or recurrent malignancy is around 35%; 55% have high preoperative risk and the surgeon’s decision not to perform reversal reaches 10%3.

Our experience shows similar results in terms of the percentage of patients who reach the stage of reversal, while the causes that prevented reversal in the remaining patients were advanced cancer, surgeon’s decision not to reverse due to advanced age and mental illness. Two patients (9%) declined reversal. Despite some reports,6,7 there are no validated guidelines to help us select patients suitable for reversal according to the risk of complications. This means that we must still consider baseline disease, functional status, nutritional status, associated comorbidity and preoperative risk3. In addition to patient-related factors, timing to reversal and the experience of the surgeon and surgical team should also be considered6,8-15.

The time interval between the Hartmann operation and reversal is mentioned as an important variable in terms of technique and results, but this statement lacks solid evidence and remains a controversial issue1. Some studies report greater complications when time to reversal is longer. Nevertheless, bias selection should be considered as surgeons are usually not interested in early reversal. Conversely, several studies support delayed reversal arguing that the rate of complications is lower when clinical and nutritional status has improved. In our series, mean time to reversal was 9 months, which is slightly longer than 7.63 months (range 5.6 to 13.3) reported in the literature3. In an attempt to establish a cutoff point of time to reversal actually expressing conclusive different results, we have arbitrarily divided it into periods of time. In this way we observed that morbidity increases with time. Nevertheless, we consider that this is only an observation.

We agree with the reports6,8-15 indicating that surgeon’s dedication to colorectal diseases, the availability of databases for continuous or periodic review of the results, knowledge of surgical anatomy, refinement of the surgical technique, adequate surgical strategies and appropriate patient selection will inevitably lead to better clinical outcomes. The way our experience has evolved over the years supports this point of view. Reversal of the Hartmann’s operation is associated with high rate of complications, about 30% (range 5-55%)2,3. However, we prefer -and recommendadjustment for clinical and surgical complications. Surgical complications can seriously compromise life and quality of life. Wall infections or surgical site infections can potentially lead to severe sepsis and permanent stoma. For this reason, it is convenient to apply some categorization for an adequate comparison between the different publications. In this regard, we consider that the Clavien-Dindo classification is the most adequate for this purpose10.

Although this study is not intended to perform a multivariate analysis of the causes of morbidity, we may say that complications were more common in benign conditions undergoing emergency Hartmann’s operation, in reversal using the conventional approach, when time to reversal was > 1 year, and when a diverting protective ileostomy was not left. Anastomotic leak has three possible clinical manifestations: diffuse peritonitis when bowel content leaks free into the cavity, a colocutaneous fistula with discharge of fecal material through a drain and without major clinical consequences, and a pelvic collection with fever, pain and a torpid postoperative course. The therapeutic decisions taken at this time will be decisive in morbidity, mortality and likelihood of a permanent stoma. Peritonitis requires an urgent reoperation with lavage of the cavity and creation of an ostomy, either by redoing the terminal iliac colostomy or a diverting loop ostomy located in the transverse colon or distal ileum leaving the anastomosis in situ. In case of a colocutaneous fistula leaking through a drain and without a collection in the trajectory, watchful waiting can be considered until spontaneous closure occurs. In the presence of high output or if there is a collection in the trajectory, a diverting ostomy with percutaneous drainage of the collection can be performed. Pelvic collections may be managed by percutaneous drainage with or without diverting ostomy. When managing an anastomotic leak, we suggest not to undo the anastomosis and not to redo the terminal iliac colostomy whenever possible. This approach will surely result in a permanent stoma. In our experience, the percentage of anastomotic leak was 11.5%, similar to that reported in the literature2. There are almost no reports on the use of diverting ostomy for protection during reversal. Some authors only mention it without providing information17; others provide further details9-12. This strategy is based on the same concept of a diverting protective ostomy performed in scheduled or emergency colorectal resection with primary anastomosis.

We advocate for this strategy because we are convinced that it can reduce the risk of permanent ostomy. Let us remember that whenever an anastomotic leak occurs, we will most likely have to perform an ostomy, either by undoing the anastomosis and redoing the terminal iliac colostomy or by performing a loop ileostomy or a transverse loop colostomy. But at this point, the patient will certainly already be experiencing a life-threatening peritonitis. If this situation is overcome, both the patient and the surgeon will be reluctant to make another attempt later. We suggest such ostomy only in cases of difficult anastomosis and when there is a history of radiotherapy. The laparoscopic approach has been presented as a possible intervention since 199318. In Argentina, there are few publications using this approach19-22. This topic was presented at Academia Argentina de Cirugía by J. C. Albertengo in 199519 and N. Amato in 200220. Several publications show that the open approach has common complications in the abdominal wall, as hematoma, wound site infection and evisceration in the immediate postoperative period, and incisional hernias in the long-term follow-up. The laparoscopic approach produces less postoperative ileus, shorter length of hospital stay, rapid recovery and, above all, avoids laparotomy, which increases the risk of the aforementioned complications. However, some publications have not found any differences8,10,22-29. Our experience with the laparoscopic approach shows favorable results in terms of length of hospital stay, reoperations, morbidity adjusted for complications grade III and IV of the Clavien-Dindo classification and anastomotic leak. Furthermore, our conversion rate (9.5%) is lower than that reported in the literature, which is close to 20%25,26,22,28,29.

We consider that the laparoscopic approach is an extremely useful tool in this procedure, but its use requires training. In our experience, it is here to stay. Final considerations: the review of the literature confirms that there are still unanswered questions, as the best way to select patients, the choice of the appropriate timing and the most convenient approach; we advocate and advise the use of diverting protective ostomy in special situations. Finally, we conclude that the results obtained are similar to those published, and our experience motivates us to continue choosing the laparoscopic approach.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Ferrara F, Parini D, Bondurri A, Veltri M, Barbierato M, Pata F, et al. Multidisciplinary Italian Study group for STOmas (MISSTO). Italian guidelines for the surgical management of enteral stomas in adults. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23(11):1037-56. [ Links ]

2. Jørgensen JB, Erichsen R, Pedersen BG, Laurberg L, Iversen LH. Stoma reversal after intended restorative rectal cancer resection in Denmark: nationwide population-based study. BJS Open. 2020;4(6):1162-71. [ Links ]

3. Hallam S, Mothe BS, Tirumulaju RMR. Hartmann’s procedure, reversal and rate of stoma-free survival- Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100(4):301-7. [ Links ]

4. den Dulk M, Smit M, Peeters KC, Kranenbarg EM, Rutten HJ, Wiggers T, et al A multivariate analysis of limiting factors for stoma reversal in patients with rectal cancer entered into the total mesorectal excision (TME) trial: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:297-303. [ Links ]

5. Lindgren R, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Sjödahl R, Matthiessen P. What is the risk for a permanent stoma after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer? A six‐year follow‐up of a multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:41-7. [ Links ]

6. Jae Hyun Kang, Byung Mo Kang, Sang Nam Yoon, Jeong Yeon Kim, Jun Ho Park, Bo Young Oh, and Jong Wan Kim. Analysis of factors affecting reversal of Hartmann’s procedure and postreversal complications. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16820. [ Links ]

7. Riansuwan W, Hull TL, Millan MM, Hammel JP. Nonreversal of Hartmann’s procedure for diverticulitis: derivation of a scoring system to predict nonreversal. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(8):1400- 8. [ Links ]

8. Aydin NH, Remzi HF, Tekkis PP..: Hartmann’s reversal is associated with high postoperative adverse events. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2117-26. [ Links ]

9. Bilenca O, Rozier E, Griffero R, Ramirez E, Pastore R, Pardo D. Reconstrucción del tránsito colorectal. Relator: Santangelo Héctor. Rev Argent Cirug. 52:17:1987. [ Links ]

10. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205-13. [ Links ]

11. Gorey TF, O’Connell PR, Waldron D, Cronin K, Kerin M, Fitzpatrick JM. Laparoscopically assisted colostomy closure after Hartmann’s procedure. Br J Surg. 1993;80:109. [ Links ]

12. Kartal K, Citgez B, Koksal MH, Besler E, Akgun IE, Mihmanli M. Colostomy reversal after a Hartmann’s procedure. Effects of experience on mortality and morbidity. Ann Ital Chir. 2019;90:539-44. [ Links ]

13. Mirza KL, Wickham CJ, Noren ER, Hwang GS, Ault GT, Ortega AE, Cologne KG. Outcomes of colostomy takedown following Hartmann’s Procedure: Successful restoration of continuity comes with high risk of morbidity. Colorectal Dis. 2020. doi:10.1111/codi.15456. [ Links ]

14. Horesh N, Rudnicki Y, Dreznik Y, Zbar AP, Gutman M, Zmora O, Rosin D. Reversal of Hartmann’s procedure: still a complicated operation. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(2):81-7. [ Links ]

15. Horesh N, Lessing Y, Rudnicki Y, Kent I, Kammar H, Ben-Yaacov A, et al. Considerations for Hartmann’s reversal and Hartmann’s reversal outcomes-a multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(11):1577-82. [ Links ]

16. Keck JO, Collopy B T, Ryan P, Fink R, Mackay J, Woods RJ. Reversal of Hartmann’s procedure: effect of timing and technique on ease and safety. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(3):243-8. [ Links ]

17. Sherman KL, Wexner SD. Considerations in Stoma Reversal. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(3):172-7. [ Links ]

18. Anderson CA, Fowler DL, White S, et al. Laparoscopic colostomy closure. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3:69-72. [ Links ]

19. Albertengo JC, Zorraquin C, Villarejo N, Monges O. Relator: Casal, M. Reconstrucción colorrectal de la operación de Hartmann por videolaparoscopía asistida. Rev Argent Cirug. 1995;68: 158-62. [ Links ]

20. Amato N, Sternberg E, Pertierra P, Muhlemberg C, Clérici M. Reconstrucción de la continuidad intestinal por laparoscopía luego de operación de Hartmann. Relator: Iribarren, C. Rev Argent Cirug. 2002;83:166-75. [ Links ]

21. Barbarisi M, Sarra C, Pitaco J, Alfonso D, Gómez E, Minetti A. La vía laparoscópica para la reconstrucción del tránsito intestinal luego de la operación de Hartmann. Consideraciones técnicas y resultados. Rev Argent Cirug. 2012;102(1-3):28-36. [ Links ]

22. Barbarisi M, Sarra CA, Pitaco JI, Alfonso DA, Gómez E y Minetti AM. La vía laparoscópica para la restitución del tránsito intestinal luego de la operación de Hartmann. Consideraciones técnicas y resultados. Rev Argent Cirug. 2012;102(1-3):28-36. [ Links ]

23. Faure JP, Doucet C, Essique D, Badra Y, Carretier M, Richer JP, Scépi M. Comparison of conventional and laparoscopic Hartmann´s procedure reversal. Surg. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2007; 17:495- 99. [ Links ]

24. Guerra F, Coletta D, Del Basso C, Giuliani G, Patriti A. Conventional Versus Minimally Invasive Hartmann Takedown: A Meta-analysis of the Literature. World J Surg. 2019;43(7):1820-8. [ Links ]

25. Mazeh H, Greenstein AJ, Swedish K, Nguyen SQ, Lipskar A, Weber KJ, et al. Laparoscopic and open reversal of Hartmann’s procedure-a comparative retrospective analysis. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 496-502. [ Links ]

26. Masoni L, Mari FS, Nigri G, Favi F, Pindozzi F, Dall’Oglio A, Pancaldi A, Brescia A. Total laparoscopic reversal of Hartmann’s procedure. Am Surg. 2013;79(1):67-71. [ Links ]

27. Horesh N, Lessing Y, Rudnicki Y, Kent I, Kammar H, Ben-Yaacov A, et al. Comparison between laparoscopic and open Hartmann’s reversal: results of a decade-long multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2018; 32: 4780-4787. [ Links ]

28. Yang PF, Morgan MJ. Laparoscopic versus open reversal of Hartmann’s procedure: a retrospective review. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84(12): 965-9. [ Links ]

29. Celentano V, Giglio MC, Bucci L Laparoscopic versus open Hartmann’s reversal: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(12):1603-15. [ Links ]

Received: March 25, 2021; Accepted: May 24, 2021

text in

text in