Neuralgic amyotrophy (AN), also known as Parsonage- Turner syndrome, paralytic brachial neuritis, idiopathic brachial plexopathy, brachial plexus neuropathy, or acute brachial radiculitis, is an entity that affects the brachial plexus. In the UK it is estimated at around 1-3 / 100,000 inhabitants / year1. In addition, Borrelia burgdorferi infec tion (Lyme disease) is a rare but potentially treatable cause of AN2.

Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is considered rare in Lyme disease3,4. The long-term recovery profile of diaphragm function is uncertain; it has been described from a substantial improvement to the need to use long-term mechanical ventilation3,4. The gold standard for the diagnosis of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis is the determination of transdiaphragmatic pressure (Pdi)5,6, a study that has been reported on few occasions.

We present a case of AN associated with Borrelia infection and bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis that pro vides a detailed follow-up of the spirometric evolution, the maximum static pressures in the mouth and the trans diaphragmatic pressure from the onset of symptoms and in the long term. This case allows us to know one of the possible evolutionary profiles of diaphragmatic dysfunction in AN due to borreliosis.

Clinical case

A 63-year-old woman with arterial hypertension (medicated with enalapril 10 mg / day) and obesity (BMI 38.5 kg/m2). She consulted for neck pain, shoulder girdle and both upper limbs and functional impotence of 48 hours of evolution. The pain was of sudden onset, continuous, of intensity 10/10, without an antalgic position. She had no history of viral infection, recent vaccination, strenuous exercise, surgery, trauma, or a family history of hereditary AN. The pain partially improved with the administration of 5 mg subcutaneous morphine, but it evolved with orthopnea and O2 desaturation. On physical examination, she had 36.5 °C and blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg. Exami nation of muscle strength showed weakness (4+/5) in bilateral shoulder abduction and distal weakness in common extensor digits (4+/5); in left upper limb. She had pain and dysesthesia in the periscapular region and bilateral upper limbs without defined distribution and winged scapula. Deep sensitivity and tendon reflexes were preserved, the cranial nerves and taxia were normal. There were no fasciculations or atrophy.

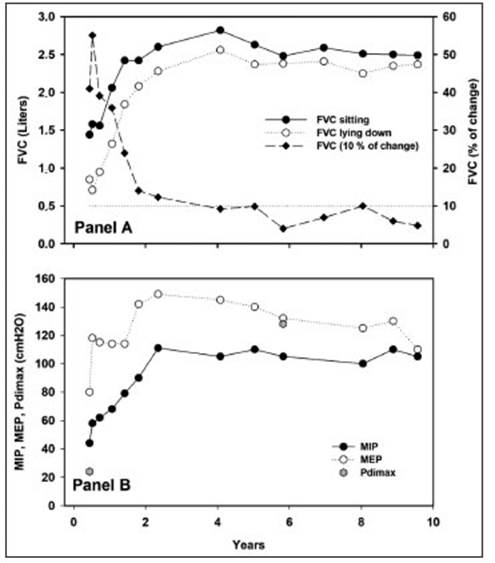

The respiratory examination showed the use of accessory neck muscles, a respiratory rate of 20 bpm, decreased air intake at both bases, orthopnea, and paradoxical breathing of the abdomen. The chest radiograph showed elevation of both hemidiaphragm. The fluoroscopy showed the absence of mobility of the right hemidiaphragm and a marked decrease in the excursion of the left hemidiaphragm. Seated arterial blood gas (FiO2 0.21) showed SaO2 96%, PaO2 75.3 mmHg, PaCO2 33.3 mmHg, pH 7.45, bicarbonate 22.6 mEq/l, (A/a) PO2 33.4 mmHg, lactate 1, 8 mmol/l. The rest of the routine laboratory tests were normal. Pulmonary function tests showed a seated forced vital capacity (FVC) of 1,440 ml (47% predicted7); the fall in supine position was 41%. The FEV1/FVC ratio was 93%. The maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressures (MIP and MEP) were 44 cmH2O (63% predicted) and 80 cmH2O (104% predicted), respectively8. Maximum transdiaphragmatic pres sure (Pdi) was 24 cmH2O (19% predicted). The maximum Pdi of the last control performed (Figure 1) was 128 cmH2O (105% predicted)9.

Fig. 1 Respiratory functional studies. A: Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) sitting (y-axis from the left) and the percentage of change between both measurements (y-axis from the right). The horizontal dotted line corresponds to the normal upper limit of the FVC drop. B: maximum inspiratory (MIP) and expiratory (MEP) pressures. The two determinations of maximum transdiaphragmatic pressure (Pdimax) are observed at baseline and six years

Neurophysiological studies showed prolonged distal mo tor latencies and reduced compound muscle action potential amplitude in both median nerves. In the left median nerve, the sensory latency was prolonged, and the amplitude of the sen sory nerve action potential was reduced. Spontaneous activity was observed in the electromyography in the supraspinatus, triceps, biceps, common extensor of the left fingers and ser ratus anterior. Stimulation of the phrenic nerves in the neck evoked no compound muscle action potential or discernible mechanical response (bilateral inexcitability).

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) presented lymphocytic pleo cytosis in two lumbar punctures. IgM-IgG anti-Borrelia burg dorferi seroconversion was determined. Initially weak positive IgM and positive IgG with a titer of 1/160, while at 30; 45 and 90 days’ serum IgM titers were negative, while those of IgG were 1/640; 1/1460 and 1/1280.

Initial treatment with non-steroidal analgesics and opiates produced mild pain relief, while there was a significant de crease with meprednisone 80 mg/day and doxycycline 100 mg BID. Due to the presence of orthopnea and desaturation, non-invasive ventilation (IPAP/EPAP 18/4 cmH2O respectively) was indicated, with clear improvement in ventilatory mechanics and orthopnea. The respiratory functional evolution of the maxi mum mouth pressures and the Pdi is observed in Figure 1.

The patient evolved favorably, with improvement in pain and functional impotence within a week and was discharged with indications for early and individualized rehabilitation that she did not comply with. After six months, she presented mild persistence of pain in the cervico-dorsal region and reduced BiPAP requirements from 12 hours to 6 hours a day at night. At eight months the muscle strength in the upper limbs was 5/5. At 16 months, after the event, she stopped requiring BiPAP; she did not report orthopnea, although functional recovery was not complete (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This case of AN associated with Borrelia infection and bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis allows us to know one of the possible evolutionary profiles of diaphragmatic dysfunction in this condition.

The abrupt onset with severe pain followed by irregular weakness in the distribution of the brachial plexus and the presence of denervation on EMG were consistent with AN10. The diagnosis of Borreliosis was made based on CSF findings and seroconversion. Antibody tests against B. burgdorferi should be considered an adjunct to clinical diagnosis since they cannot establish or exclude the di agnosis of Lyme disease by themselves. In our case, the finding of seroconversion and the clinical picture support the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Our patient resided in Buenos Aires, and her last trip outside the city (Misiones province) was 18 months ago. In Argentina, Stanchi et al. identified antibodies against B. burgdorferi in a group of agricultural workers with arthritis, while Cicuttin et al. reported Borrelia spp. in ticks and birds of a protected urban area in the city of Buenos Aires11,12.

The orthopnea, a fall of more than 30% in FVC in the supine position, was compatible with bilateral diaphrag matic paralysis11. Low MIP and the need for BiPAP are in line with that diagnosis. The maximum Pdi less than 30 cmH2O confirmed the presumption of diaphragmatic paralysis5,13. The maximum Pdi is an invasive study and careful attention to the details of the technique is required to obtain reliable measurements. The measurement of the Pdimax remains the gold standard of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis6,14. Unlike other neurophysiological and imaging techniques, Pdimax provides an objective measure of the pressure developed by the diaphragm; its value is pro portional to the force generated by it5,11,14, while it is not possible to predict Pdi response values from the recording of the compound action potential of the diaphragm, or the ultrasound of the diaphragm6.

A recent study modeled the course of recovery from NA diaphragm dysfunction not associated with borreliosis15. Only 31% of their 16 subjects studied achieved normal FVC, and even those with apparent full recovery had re sidual diaphragm deterioration on more detailed testing. The recovery course was prolonged, with a time to mid-point of recovery of almost two years. The authors did not report other identifiable etiologies15. With the diagnosis of borreliosis, there are a few cases of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. In such cases, the magnitude and recovery time of the diaphragm were not reported3,4,16.

In our case, it was possible to carry out clinical follow-up and various respiratory variables from the onset of symptoms and over ten years (Fig. 1). At four years after the onset of the disease, recovery was complete. Although it is speculative, it is possible to observe that both the recovery of the FVC, the difference between the FVC sitting and lying down and the maximum static pressures evolved with a substantial improvement in the first phase of follow-up and in a non-linear way. Unfortunately, we do not yet have other similar data to establish trends or evolutionary patterns. The patient used nocturnal NIV and, with the respiratory functional improvement, orthop nea ceased and was able to dispense with the nocturnal ventilatory support.

This clinical case of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis due to AN due to borreliosis reaffirms the importance of studying the causes that can produce AN and provide a detailed follow-up of the recovery of the diaphragm in the long term that allows establishing one of the possible evolutionary patterns of said recovery.