Introduction

Our understanding of angiosperm phylogeny has undergone a revolution over the past three decades, largely due to two spectacular advances in the science of systematic botany (Judd et al., 2015). With the advent of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology (Saiki et al., 1988), direct comparison of the nucleotide sequences of organismal DNA became possible. Secondly, phylogenetic analysis has become the standard methodology for testing hypotheses of phylogeny among organisms in systematic biology (Wiley, 1981; Felsenstein, 2004) based upon principles formally enumerated by Hennig (1966). To the parsimony method (Kitching et al., 1998) has been added both maximum likelihood (Huelsenbeck & Crandall, 1995) and Bayesian analysis (Beaumont, 2010), which have proven valuable in dealing with large DNA sequence datasets.

The precise relationship of Amaryllidaceae J.St.-Hil. to other Asparagales remained elusive until Fay & Chase (1996) used the plastid gene rubisco (rbcL) to argue that Agapanthus L’Hér., Alliaceae Borkh., and Amaryllidaceae form a monophyletic group (also evident in Chase et al., 1995a, b), and that together they are related most closely to Hyacinthaceae Batsch ex Borkh. s.s. and the resurrected family Themidaceae Salisb. (the former tribe Brodiaeeae of Alliaceae), both now classified as subfamilies within a broad circumscription of Asparagaceae Juss. (APG, 2009). They recircumscribed Amaryllidaceae to include Agapanthus, previously included in Alliaceae, as subfamily Agapanthoideae Endl. Subsequent analyses of multiple DNA sequences from both the chloroplast and nuclear genomes have shown quite strongly that Agapanthus, Amaryllidaceae, and Alliaceae represent a distinct lineage within the monocot order Asparagales Link (Meerow et al., 1999; Fay et al., 2000), but the exact relationships among the three groups have been difficult to resolve with finality (Graham et al., 2006); APG II (APG, 2003) recommended treating all three as a single family, Alliaceae (which had nomenclatural priority at that time), and more emphatically in APG III (APG, 2009), but as Amaryllidaceae, reflecting the successful proposal for superconservation of the name (Meerow et al., 2007). Current consensus has Allioideae Herb. and Amaryllidoideae Burnett as sister groups, and Agapanthoideae sister to both (Baker et al., 2022).

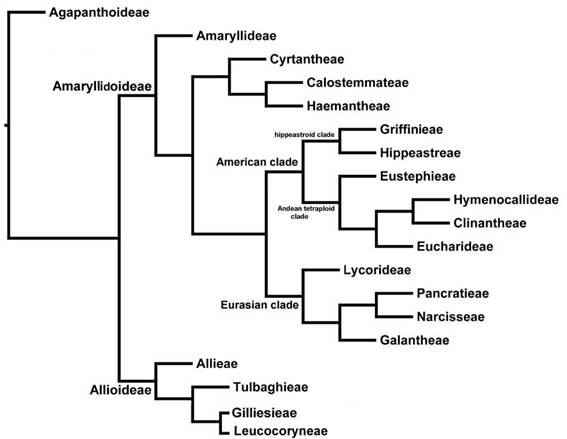

Based on the cladistic relationships of chloroplast DNA sequences (Ito et al., 1999; Meerow et al, 1999) all three subfamilies originated in Africa (Gondwanaland) and infrafamilial relationships are resolved along biogeographic lines (Fig. 1). Subfamily Amaryllidoideae, the largest in number of genera, has colonized all continents except Antarctica. Janssen & Bremer (2004) estimated the age of the family at 87 million years before present (MYBP). The only fossil for the family is from early Eocene western North America and was diagnosed as allied to Allioideae (Pigg et al., 2018); contested by Friesen (2022). A leaf fossil from Colombia assigned by Wing et al. (2018) to Amaryllidaceae is at best ambiguous.

Agapanthoideae

The genus Agapanthus (subfamily Agapanthoideae) is restricted to South Africa and consists of six to 10 species of rhizomatous, evergreen or deciduous perennials, most with blue flowers (Snoeijer, 2004). The flowers have superior ovaries, and the genus contains saponins. To date, no molecular studies have been conducted to estimate the species phylogeny of this relatively small genus.

Allioideae

Allioideae is represented in Africa by the South African endemic genus Tulbaghia L., and a single species of Allium L., but is most diverse generically in southern South America (Chile and Argentina). Three tribes were recognized by some (Chase et al., 2009; Escobar et al., 2020): Allieae Dumort., Gilliesieae Baker and Tulbaghieae Endl. ex Meisn. Leucocoryneae Ravenna is now accepted as a fourth distinct tribe (Sassone et al., 2018), of which the first and third consist of only a single genus, Allium and Tulbaghia (the monotypic genus Prototulbaghia Vosa appears nested within Tulbaghia (Stafford et al., 2016)).

The subfamily is characterized by solid styles, superior ovaries and the unique allyl sulfide chemistry that gives many members their characteristic garlic odor. Monotypic Allieae is the largest tribe, entirely due to the speciose genus Allium (Friesen, 2022; Li et al., 2010).

Tulbaghieae

The South African endemic genus Tulbaghia consists of 20-30 species and is badly in need of a thorough taxonomic revision. Vosa (2007) recognized a monotypic segregate genus Prototulbaghia that in a recent molecular study resolved as sister to one subclade of Tulbaghia spp. (Stafford et al., 2016). Vosa (2009) presented a synoptic classification for the genus, distinguishing species groups (sections) primarily on the basis of the morphology of the staminal corona, recognizing 23 species, but Stafford et al. (2016) suggest that there may be as many as 30. Tulbaghieae is endemic to South Africa and is sister to the South American tribes Gilliesieae (Costa et al., 2020; Escobar et al., 2020) and Leucocoryneae (ca. six genera Sassone & Giussani, 2018).

Allieae

Allium contains over 900 species (Herden et al., 2016) and is one of the largest genera of monocots known. More than 50 species are used as edible, medicinal and ornamental crops. Variable morphologically as well as ecologically, it has spread across the Holarctic region, inhabiting dry subtropics to boreal vegetation. Only a single species of Allium occurs outside the Holartic zone, A. synnotia G.Don (syn. A. dregeanum Kunth), native to South Africa (de Wilde-Duyfjes, 1976; de Sarker et al., 1997), though Friesen (2022) suggests that it may have been introduced by early European colonists. An Old World center of diversity encompasses the Mediterranean Basin to Central and Eastern Asia, with a second smaller one in western North America. Friesen (2022), Friesen et al. (2006) and Li et al. (2010) review the infrageneric taxonomic history of this complex genus. Molecular studies have either addressed the phylogenetic relationships of the entire genus (Mes et al., 1997; Dubouzet & Shinoda, 1999; He et al., 2000; Fritsch & Friesen, 2002; Friesen et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010, 2016b; Xie et al., 2020) or specific subgenera and sections Amerallium Traub: Samoylov et al., 1995, 1999; Cyathophora (R.M.Fritsch) R.M.Fritsch: Li et al., 2016a Melanocrommyum (Webb & Berth.) Rouy: Dubouzet & Shinoda, 1998; Mes et al., 1999; Gurushidze et al., 2008, 2010; Fritsch et al., 2010, Rhizirideum (G. Don ex Koch) Wendelbo: Dubouzet et al., 1997, section Cepa (Mill.) Prokh: Gurushidze et al., 2007, origins of A. ampeloprasum L. horticultural races and section Allium: Hirschegger et al., 2010). Other molecular phylogenetic investigations have been concerned with the origins of economically important Allium crops (e.g. Friesen & Klaas, 1998; Friesen et al., 1999; Blattner & Friesen, 2006; Friesen, 2022). Nguyen et al. (2008) examined the phylogeny of the western North American species and their adaptation to serpentine soils.

Friesen et al.'s (2006) analysis of 195 species of Allium using the ITS region of nrDNA presented a new subgeneric classification consisting of 15 monophyletic subgenera, and this is still mostly accepted. Earlier, Friesen et al. (2000) showed that the anomalous Milula Prain with a spicate inflorescence was nested within the Himalayan species of Allium. Nectaroscordum Lindl. and Caloscordum Herb. are also retained within Allium. Li et al. (2010) used ITS sequences along with the intron of the plastid gene rps16 across over 300 Allium taxa and included a biogeographical analysis of the genus. Three major clades are consistently resolved (Fritsch, 2001; Fritsch & Friesen, 2002; Friesen et al., 2006; Li et al., 2010), which Xie et al.'s (2020) whole plastome phylogeny supports as well. Subgenera Amerallium, Anguinum G.Don ex W.D.J.Koch) N.Friesen, Vvedenskya (Kamelin) R.M.Fritsch, Porphyroprason (Ekberg) R.M.Fritsch and Melanocrommyum originated in eastern Asia. The putatively oldest lineage consists of only bulbous plants (subgenera Nectaroscordum, Microscordum (Maxim.) N.Friesen and Amerallium) that only rarely produce a rhizome (Fritsch & Friesen, 2002). The second clade includes subgenera Caloscordum, Anguinum, Vvedenskya, Porphyroprason and Melanocrommyum, and the third subgenera Butomissa (Salisb.) N. Friesen, Cyathophora, Rhizirideum, Allium, Cepa, Reticulatobulbosa (Kamelin) N. Friesen and Polyprason Radie. The latter two contain both rhizomatous and bulbous species. The third clade was the most poorly resolved in these analyses and includes a number of non-monophyletic subgenera (Li et al, 2010), but resolution and levels of support were greatly increased with analysis of whole plastomes (Xie et al., 2020). A scenario of rapid radiation was proposed for this clade. The first two clades contain both Old and New World species; almost all of the western North American species are classified in subgenus Amerallium (Nguyen et al., 2008), which has sparingly extended to central and eastern North America. The only other North American species are members of subg. Anguinum (Li et al, 2010; Xie et al., 2020).

Costa et al. (2020) estimated the age of Allioideae as ca. 63 million years and hypothesized that the Indian plate rafted Allieae to the northern hemisphere from which the genus Allium (ca. 52 MYBP) diversified via polyploidy and geographic spread throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Friesen (2022) supported this hypothesis.

Gilliesieae and Leucocoryneae

The tribes Gilliesieae and Leucocoryneae are entirely restricted to the American continents and are most diverse in southern South America, especially Argentina and Chile, and includes such established ornamental bulb crops as Ipheion Raf. and Leucocoryne Lindl. Only one species of Nothoscordum Kunth extends outside of that region, and may be adventive. The sister relationship of these tribes to Tulbaghieae (Fay & Chase, 1996; Fay et al, 2006) suggests an austral entry into South America, perhaps via Antarctica, as has been suggested for many groups showing a similar biogeographic scenario (Raven & Axelrod, 1974). Unfortunately, generic limits within the group remain problematic, with many species having been variously treated as members of diverse genera (Rahn, 1998; Zollner & Amagada, 1998; Rudall et al., 2002; Fay et al., 2006).

The two tribes are immediately separable by the symmetry of the flowers; all Gilliesieae are zygomorphic, and all Leucocoryneae are actinomorphic. The latter also alone possess septal nectaries (Rudall et al, 2002). Both tribes show greater variability in karyotype than either Allium or Tulbaghia (Costa et al., 2020). A combination of plastid and ribosomal DNA sequences robustly supports the two floral morphological clades (Fay et al, 2006; Pellicer et al., 2017; Sassone & Giussani, 2018). Interestingly, the zygomorphic flowers of Gilliesia Lindl. are hypothesized to be insect mimics with a pseudocopulatory pollination syndrome (Rudall et al., 2002).

Escobar et al. (2020) applied ITS and plastid rbcL and trnL-F sequences to explore generic limits in the Gilliesieae. Two major clades were well-supported: Clade I comprises the genera

Gilliesia, Gethyum Phil. and Solaria Phil., and Clade II, Miersia Lindl. and Speea Loes. However, Gilliesia, Gethyum and Miersia were all found to be paraphyletic, resulting in the recognition of the monotypic genus Ancrumia Harv. ex Baker. Schickendantziella Speg. and Trichlora Baker were not represented in the sampling. García et al. (2022a) resolved the same phylogenetic tree, and published two novel species of Miersia.

Sassone and colleagues have studied Leucocoryneae extensively (Sassone & Arroyo-Leuenberger, 2018; Sassone & Giussani, 2018; Sassone et al., 2013; Sassone et al, 2018), and the taxonomic history of the tribe is summarized in Sassone & Giussani (2018).

This tribe consists of six South American genera with ca. 100 species (Sassone et al., 2014a): Beauverdia Herter (four spp., Sassone et al., 2014b), Ipheion (three spp., Sassone et al., 2014a), Latace Phil. (two spp., Sassone et al., 2015), Leucocoryne (15 spp., Muñoz & Moreira, 2000), Nothoscordum (20-80 spp.), and Tristagma Poepp. (12 spp.; Arroyo-Leuenberger & Sassone, 2016). However, both Tristagma and Nothoscordum resolve as biphyletic (Pellicer et al, 2017; Sassone & Giussani, 2018), and Beauverdia, with both white and yellow uniflorous species, is nested within the latter. For this reason, Pellicer et al. (2017) argued that Beauverdia should be placed into synonomy with Nothoscordum. Most recently García et al. (2022b) described a new monotypic genus in the Leucocoryneae, Atacamallium Nic. García, which resolved as sister to the genus Leucocoryne.

Amaryllidoideae

The largest subfamily of Amaryllidaceae in number of genera is Amaryllidoideae (Fig. 1). This subfamily is also economically important, albeit for its large number of ornamental bulbs rather than any food value. It is characterized by an inferior ovary, a unique group of alkaloidal compounds, many with bioactive properties (Meerow & Snijman, 1998; He et al, 2015), and base chromosome number of x = 11 (Meerow & Snijman, 1998).

Tribe Amaryllideae, entirely southern African with the exception of pantropical Crinum L., is sister to the rest of Amaryllidaceae with very high bootstrap support in Meerow et al.'s (1999) analysis of plastid genes (Fig. 1). The remaining two African tribes of the family, Haemantheae Hutch. (including subtr. Gethyllidinae Dumort) and Cyrtantheae Traub (consisting of only Cyrtanthus Ait.), were well supported, but their position relative to the Australasian Calostemmateae D.Müll.-Doblies & U.Müll.Doblies and a large clade comprising the Eurasian and American genera, was not clear. Most surprising, the Eurasian and American elements of the family were each monophyletic sister clades. Ito et al. (1999) resolved a very similar topology for a more limited sampling of Amaryllidaceae and related asparagoids using plastid matK sequences. Plastid ndhF sequences (Meerow & Snijman, 2006) resolved Cyrtantheae as sister to a clade of Calostemmataeae and Haemantheae.

Amaryllideae

Almost all of the generic diversity of the tribe Amaryllideae is confined to South Africa (Snijman & Linder, 1996). Compared to other tribes in Amaryllidaceae, Amaryllideae is marked by a large number of synapomorphies (Snijman & Linder, 1996; Meerow & Snijman, 1998): extensible fibers in the bulb tunics, bisulculate pollen with spinulose exine, scapes with a sclerenchymatous sheath, unitegmic or ategmic ovules, and nondormant, water-rich, nonphytomelaninous seeds with chlorophyllous embryos. A few of the genera extend outside of South Africa proper, but only Crinum, with seeds well suited to oceanic dispersal (Koshimizu, 1930), ranges through Asia, Australia, and America. The tribe is the first branch within the subfamily (Ito et al., 1999; Meerow, 2010; Meerow et al., 2000; Meerow & Snijman, 2006). Snijman and Linder’s (1996) phylogenetic analysis of the tribe based on morphological, floral and seed anatomical, and cytological data resulted in recognition of two monophyletic subtribes: Crininae Baker (Boophone Herb., Crinum, Ammocharis Herb., and Cybistetes Milne-Redh. & Schweick., the latter now transferred to Ammocharis (Snijman & Williamson, 1994) and Amaryllidinae Walp. (Amaryllis L., Nerine Herb., Brunsvigia Heist., Crossyne Salisb., Hessea Herb., Strumaria Jacq., and Carpolyza Salisb. Carpolyza has been transferred to Strumaria (Meerow & Snijman, 2001). Meerow et al.’s (1999) incomplete sampling of this tribe for three plastid sequences resolved Amaryllis as sister to the rest of the tribe. Weichhardt-Kulessa et al. (2000) presented an analysis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences for a part of the tribe (subtribe

Strumariinae sensu D. & U. Müller-Doblies [1985, 1996]). Meerow & Snijman (2001) analyzed morphology and ITS sequences across the entire tribe. Amaryllis is sister to the remaining genera, followed by Boophone. All other genera were included in two clades conforming to Snijman & Linder’s (1996) subtribes Amaryllidinae (less Amaryllis, thus now Strumariinae) and Crininae (less Boophone), and Carpolyza was transferred into Strumaria (Meerow & Snijman, 2001).

Meerow et al. (2003) presented phylogenetic and biogeographical analyses of nrDNA ITS and plastid trnL-F sequences for all continental groups of the large, pantropical genus Crinum and related genera. Their results indicated that C. baumii Harms is more closely related to Ammocharis than to Crinum sensu stricto (s.s.). Three clades are resolved in Crinum s.s. The first one unites a monophyletic American group with tropical and North African species. Meerow et al. (2003) hypothesized that emergent aquatic tropical African species with actinomorphic perianths were likely the sister group to the American species, which was shown to be the case by Kwembeya et al. (2007). The second clade included all southern African species and the Australian endemic C. flaccidum Herb. The third includes monophyletic Madagascar, Australasian and Sino-Himalayan clades, with southern African species. The salverform, actinomorphic perianths of subg. Crinum appear to have evolved several times in the genus from ancestors with zygomorphic perianths (subg. Codonocrinum Willd. ex Schult.f.), thus neither subgenus is monophyletic. Biogeographical analyses place the origin of Crinum in southern Africa. The genus underwent three major waves of radiation corresponding to the three main clades resolved in the trees. Two entries into Australia of the genus were indicated, as were separate Sino-Himalayan and Australasian dispersal events. These results were confirmed by Kwembeya et al. (2007), including the origin of the endemic American species from tropical west African spp.

Calostemmateae, Cyrtantheae and Haemantheae

The three tribes Calostemmateae, Cyrtantheae and Haemantheae form a clade that is sister to the American and Eurasian tribes of the subfamily (Fig. 1; Meerow et al., 1999; Meerow & Snijman, 2006), though their exact relationships to each other remain ambiguous (Meerow & Snijman, 2006; Bay-Schmidt et al., 2010).

Calostemmateae consists of two Australasian genera (Proiphys Herb., pseudopetiolate forest understory herbs of Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and tropical Australia; and Calostemma R. Br., endemic to Australia). The indehiscent capsules of both genera are similar in appearance to the unripe berry-fruits of Scadoxus Raf. and Haemanthus L. (Haemantheae), but early in the development of the seed, the embryo germinates precociously, and a bulbil forms within the capsule and functions as the mature propagule (Rendle, 1901). A reasonable hypothesis is that the lineage represents an early entry into Australia directly from Africa.

Cyrtantheae consists of a single genus. Cyrtanthus is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, with well over 90% of its species concentrated in South Africa (Dyer, 1939; Reid & Dyer, 1984). With about 55 species it is the largest genus of southern Africa’s Amaryllidaceae (Snijman & Archer, 2003) and one of the largest in the family overall (Snijman & Meerow, 2010). The genus exhibits a high level of floral morphological diversity which is unparalleled in any other genus of the family. Conversely, the genus shows great consistency in chromosome number, with 2n = 16 characteristic of most, if not all, of the species (Wilsenach, 1963; Ising, 1970; Strydom et al., 2007). It is also the only African genus with the flattened, winged, phytomelaninous seed, so common in the American clade of the family (Meerow & Snijman, 1998). Snijman & Meerow (2010) explored the phylogeny of the genus in the context of floral and ecological adaptation using plastid ndhF and nuclear ribosomal DNA.

Haemantheae is the only group of Amaryllidaceae that have evolved a baccate fruit (Meerow et al., 1999; Meerow & Clayton, 2004). It is entirely African, and like Cyrtanthus, most of its diversity is in South Africa (Meerow & Snijman, 1998). Meerow & Clayton (2004) analyzed plastid trnL-F and nrDNA ITS sequences across the tribe. Two main clades are resolved, one comprising the monophyletic rhizomatous genera Clivia Lindl. and Cryptostephanus Welw. ex Baker, and a larger clade that unites Haemanthus and Scadoxus as sister to an Apodolirion Baker/Gethyllis L. subclade.

The Eurasian clade (Lycorideae, Galantheae, Narcisseae, and Pancratieae)

The Eurasian clade of the Amaryllidaceae (Fig. 1) contains the members of the family that have adapted to the highest latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, and also those with the greatest economic value as spring flowering temperate zone garden plants (Narcissus L., Galanthus L., Leucojum L.). The clade was only recently recognized as a monophyletic group, resolved as sister to the endemic American genera by plastid DNA sequences (Ito et al, 1999; Meerow et al., 1999). The Eurasian clade encompasses four tribes that were previously recognized (Meerow & Snijman, 1998): Galantheae Parl., Lycorideae Herb., Narcisseae Lam. & DC., and Pancratieae Dumort., the overall relationships of which were obscured by their diversity of chromosome number and morphology (Traub, 1963). Müller-Doblies & Müller-Doblies (1978a) earlier observed similarities between the internal bulb morphology of Ungernia Bunge (Lycorideae) and Sternbergia Waldst. & Kit. (Narcisseae). With the exception of the Central and East Asian Lycorideae, the clade is centered within the Mediterranean region (Meerow & Snijman, 1998; Lledó et al., 2004). There are 11 genera in the clade, comprising ca. 120 spp., with Lycoris Herb. (ca. 20 spp.) and Narcissus L. (40 spp.) the largest genera (Meerow & Snijman, 1998).

Lledó et al. (2004) presented a cladistic analysis of the clade that focused on the relationships of Leucojum and Galanthus using plastid matK, nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences, and morphology. Leucojum was revealed as paraphyletic, and the genus Acis Salisb. was resurrected to accommodate the linear-leaved Mediterranean Leucojum species with solid scapes. While their sampling within these three genera was extensive, only a single species each of the genera Pancratium L., Sternbergia, Narcissus, and Vagaria Herb., along with the monotypic Lapiedra Lag., were used as outgroups. Hannonia Braun-Blanq. & Maire was not included. Consequently, the phylogenetic relationships of the entire clade were not explicitly examined in their analyses. A similar case holds for Graham & Barrett’s (2004) study of floral evolution in Narcissus using plastid ndhF and trnL-F sequences, which included only Lapiedra and one species each of Galanthus, Leucojum, and Sternbergia as outgroups in their analyses.

Meerow et al. (2006) analyzed the clade using plastid ndhF and rDNA ITS sequences for 33 and 29 taxa, respectively; all genera were represented by at least one species. Both sequence matrices resolve the Central and East Asian tribe Lycorideae as sister to the Mediterranean-centered genera of the clade, and two large subclades were recognized within the greater Mediterranean region: Galantheae, consisting of Acis, Galanthus and Leucojum; and Narcisseae (sister genera Narcissus and Sternbergia, and Pancratium). However, there were areas of incongruence between the two markers, which disappeared when three predominantly monotypic genera, Hannonia, Lapiedra, and Vagaria, centered in North Africa, were removed from the alignments. The authors hypothesized that incomplete lineage sorting took place after the divergence of Galantheae and Narcisseae/ Pancratium from a common ancestor, with the three small or monotypic genera retaining a mosaic of the ancestral haplotypes. After the vicariant divergence of the Asian Lycorideae, North Africa and the Iberian Península are the most likely areas of origin for the rest of the clade (Meerow et al, 2006). A new genus, Shoubiaonia W.H.Qin, W.Q.Meng & Kun Liu, was recently described in Lycorideae and is sister to Lycoris and Ungernia (Qin et al., 2021).

Narcissus is the most important genus of temperate zone spring flowering bulbs in the Amaryllidaceae. The genus is taxonomically very complex (Fernandes, 1968a; Webb, 1980; Mathew, 2002), no doubt in part due to its propensity to hybridize in nature (Marques, 2010), and the many horticultural hybrids and selections (Mathew, 2002). Consequently, the number of species varies considerably in different studies. For example, Webb (1980) recognized 26 species; Fernandes (1968a) accepted 63. Blanchard (1990) favored Fernandes’ (1968a) treatment. The genus is most speciose in the Western Mediterranean area, particularly the Iberian Peninsula and NW Africa. This group is also fascinating biologically due to the occurrence of all four major classes of heterostyly, from stylar monomorphism, stigma-height dimorphism, distyly, to tristyly (reviewed in Barrett & Harder, 2005). It is the only heterostylous genus of Amaryllidaceae.

Fernandes (1968a) divided Narcissus into two subgenera, Hermione (Salisb. ex Haw.) Spach with base chromosome number x = 5, and Narcissus with x = 7. He recognized 10 sections (Apodanthae [as Apodanthi] A. Fernandes, Aurelia (J. Gay) Baker, Bulbocodii DC., Ganymedes (Haw.) Schult f., Jonquilla DC., Narcissus, Pseudonarcissus DC., Serotini Parl., Tapeinanthus (Herb.) Traub and Tazettae DC.) based on his decades of karyotypic studies in the genus (summarized in Fernandes, 1967, 1968a, b, 1975). Pérez-Barrales et al., (2003) used the short plastid intergenic spacer between trnL and trnF across a small sampling of Narcissus species and did not get much resolution beyond the two recognized subgenera. Graham & Barrett (2004) provided phylogenetic analyses of the plastid trnL-F and ndhF regions sequenced from 32 Narcissus species representing all 10 sections recognized by Fernandes (1975) and Blanchard (1990). This report strongly supported monophyletic subgenera Hermione and Narcissus, but not of all sections. Only section Apodanthae was clearly monophyletic, but several clades corresponded approximately to recognized sections (Graham & Barrett, 2004). The most robust study is that of Marques et al. (2017) who utilized plastid, mitochondrial and nrDNA (ITS) across a large sampling of species with multiple accessions. She uncovered striking incongruence between trees supported by the cytoplasmic versus the nuclear sequences, which she attributed to widescale hybridization throughout the evolutionary history of the genus. Tests for recombination in the ITS alignments supported this hypothesis. Again, only few of Fernandes’ (1968a) sections were found to be monophyletic. Konyves et al. (2019) concluded much the same in their study of Narcissus section Bulbocodii.

The sister genus to Narcissus is Sternbergia (Meerow et al., 2006), a small genus of ca. eight dwarf white or yellow cup-shaped flowered species, generally appearing in autumn. The scapes are uniflorous. It is distributed around the Mediterranean basin, with diversity and endemism highest from Greece to Israel. Two species flower in spring: S. vernalis (Mill.) Gorer & J.H.Harvey and S. candida B.Mathew. & T.Baytop, the latter the sole white-flowered species. S. lutea (L.) Ker Gawl. ex. Spreng. has been in cultivation for millennia and has naturalized in areas of northern Europe (Mathew, 1983).

Gage et al. (2011) published the most recent phylogeny of the genus and concluded that it forms two main clades: 1) S. colchiciflora Waldst. & Kit. sister to S. vernalis, S. candida and S. clusiana Boiss., and 2) S. lutea and its allies. The two spring flowering species are closely related. In the S. lutea complex, there was insufficient resolution, supporting arguments that S. sicula Tineo ex Guss. and S. greuteriana Kamari & R.Artelari are conspecific with S. lutea.

The relationship between Galanthus and Leucojum sensu lato (s.l.) has long been recognized, as has their relationship to Narcissus and Sternbergia (Müller-Doblies & Müller-Doblies, 1978b; Davis, 1999; 2001). Both genera share pendulous, predominantly white flowers, similar internal bulb morphology and poricidal anthers (Müller-Doblies & Müller-Doblies, 1978b). Unlike Narcissus, both lack a floral tube or a paraperigone (corona). Galanthus is marked by the striking length differences between the inner and outer tepal series, which are only subequal in Leucojum and Acis (Meerow & Snijman, 1998).

Galanthus consists of 18 species, mostly distributed in Europe, Asia Minor and the Near East (Davis, 1999, 2001). Stern (1956) recognized three series in Galanthus, erected primarily by leaf vernation: Nivales Beck (leaves flat), Plicati Beck (leaves plicate) and Latifolii Stern (leaves convolute). Davis (1999) combined series Nivales and Plicati into series Galanthus, and divided series Latifolii into two subseries: Glaucaefolii (Kem.-Nath.) A. P. Davis and Viridifolii (Kem.-Nath.) A.P.Davis. Molecular phylogenetic studies (Lledó et al., 2004; Larsen et al., 2010; Rensted et al., 2013) indicate that the two subseries are not monophyletic.

Leucojum s.l. originally contained 10 species (Stern, 1956), mostly occurring in the western Mediterranean area, from the Atlantic coast of Portugal and Morocco to the northern Balkans and Crimea, but today the genus comprises only two: L. vernum L. and L. aestivum L. (Lledó et al. , 2004; Meerow et al, 2006; Larsen et al., 2010), both broadly distributed in central and northern Europe, Turkey and the Caucasus. Leucojum is characterized by hollow scapes, broad leaves and clavate styles. Both species have a base chromosome number of x = 11. L. vernum, the type of the genus, is widespread in central and northern Europe. Its seeds have a pale outer testa and elaiosomes. L. aestivum is found throughout the Mediterranean and central Europe to Turkey and eastern Caucasus. It differs from L. vernum by its water-dispersed seed with a dark testa and lack of elaiosomes.

The remaining Leucojum species are now classified in the genus Acis, divided into subgenus Acis or Ruminia Parl. (Lledó et al, 2004; Meerow et al., 2006, Larsen et al., 2010), characterized by solid scapes, narrow leaves and filiform styles. The subgenera Acis and Ruminia are differentiated by the morphology of the epigynous staminal disc, six-lobed in A. subgenus Ruminia, and unlobed in A. subgenus Acis. Acis subg. Acis is the larger of the two subgenera with five species.

The American clade

In the American clade, the relationships of the endemic American genera (the entry of Crinum onto the continent is considered a separate event) were well resolved using the spacer regions of nuclear ribosomal DNA (Meerow et al, 2000a), and the major relationships have also been supported by plastid genes and introns (Meerow et al., 1999; 2000b; Meerow & Snijman, 2006; Meerow, 2010). The American genera of the family form two major subclades (Fig. 1). The first, or hippeastroid clade, are diploid (2n = 22), primarily the extra-Andean element of the family (though several of the genera do have Andean representatives), comprising the Brazilian endemic tribe Griffinieae Ravenna (Cearanthes Ravenna, Griffinia Ker Gawl. and Worsleya (Watson ex Traub) Traub) sister to genera treated as tribe Hippeastreae Herb. ex Sweet in most recent classifications (Dahlgren et al. 1985; Muller-Doblies & Muller-Doblies, 1996; Meerow & Snijman, 1998; García et al., 2019). ITS resolved monotypic Worsleya as the first branch in the tribe, and monotypic Cearanthes and Griffinia (16 species) as sister genera (Campos-Rocha et al., 2022b). A monograph of the tribe is underway (Campos-Rocha et al., 2018, 2019a, b).

Several genera within the hippeastroid clade resolved as polyphyletic (Rhodophiala C. Presl., Zephyranthes Herb.) and the possibility of reticulate evolution (i.e., early hybridization) in these lineages was hypothesized (Meerow et al., 2000; Meerow, 2010). This was confirmed with further analyses of plastome and multiple nuclear gene sequences (García et al., 2014, 2017). Hippeastreae constitutes two main clades, the subtribe Hippeastrinae Walp. and the mostly Chilean endemic subtribe Traubiinae D. Müll.-Doblies & U. Müll.-Doblies (García et al, 2014, 2017). In contrast to the Hippeastrinae, the Traubiinae exhibit a mostly tree-like pattern of evolution (García et al., 2017). García et al. (2019) presented a new classification scheme for Hippeastreae that reflects its reticulate phylogeny. Within Hippeastriinae, only two genera are recognized, Hippeastrum Herb. (two subgenera, H. subg. Hippeastrum and H. subg. Tocantinia (Ravenna) Nic.García) and Zephyranthes (five subgenera, Z. subg. Eithea (Ravenna) Nic.García, Z. subg. Habranthus (Herb.) Nic.García, Z. subg. Myostemma (Salisb.) Nic. García (= core Rhodophiala clade), Z. subg. Neorhodophiala Nic.García & Meerow subg. nov., and Z. subg. Zephyranthes). One species, Z. pedunculosa (Herb.) Nic.García & S.C.Arroyo, was designated as incertae sedis.

In the second subtribe, Traubiinae, García et al. (2019) and García & Meerow (2020) recognized four genera, the first two monotypic Traubia Moldenke and Paposoa Nic.García, Phycella Lindl. (including Placea Miers), 12 or more species all but one endemic to Chile, and the alpine Rhodolirium Phil. with two spp., both found in Chile and adjacent Argentina. There has been a great deal of cytogenetic work for the subtribe (Baeza & Macaya, 2020; Baeza et al., 2009a, 2009b, 2012, 2017).

The economically most important genus of American Amaryllidaceae subfam. Amaryllidoideae, Hippeastrum, is still not very well understood taxonomically. Hippeastrum consists of 70-100 entirely New World species, though one species, H. reginae Herb. appears to have been introduced to Africa. No modern revision of the genus has appeared since that of Traub & Moldenke (1949). The species are concentrated in two main areas of diversity, one in eastern Brazil, and the other in the central southern Andes of Peru, Bolivia, and Argentina, on the eastern slopes and adjacent foothills. A few species extend north to Mexico and the West Indies. Meerow et al. (2000a) included seven species in their molecular phylogenetic analysis of the American genera of subfam. Amaryllidoideae, representative of the biogeographic range of the genus. Their results suggested that the genus is robustly monophyletic and originated in Brazil. Campos-Rocha et al. (2022b), using 20 spp., further supported these results. García et al. (2014; 2017), using whole plastomes and multiple nuclear genes on a larger sampling of species, confirmed this. Hippeastrum reticulatum Herb., with unusual fruit and seed morphology was sister to all other species of subg. Hippeastrum, recently displaced by the morphologically unusual H. velloziflorum Campos-Rocha & Meerow (Campos-Rocha et al., 2022b). The low rates of base substitution in both plastid and nrDNA sequences, and the consistent interfertility of species -well-mined by bulb breeders (Meerow, 2009)- suggest that the genus underwent a relatively recent radiation (Oliveira, 2012). Many of the species seem to intergrade with one another. Traub & Moldenke (1949) attempted a formal subgeneric classification of the genus (as Amaryllis) based on floral morphology, but most of their infrageneric taxa do not appear to be monophyletic (Meerow & Snijman, 1998). The newly described H. velloziflorum resolves with ITS as sister to the rest of subgenus Hippeastrum. Lara et al. (2021) presented a revision of the Bolivian species, recognizing 34 native to that country, but there was no attempt to place the taxa into a phylogenetic context. Oliveira (2012) recognized 27 species (now 35) as occurring in Brazil and documented with sequence data and network analysis significant reticulation. New Brazilian species continue to be described (Oliveira et al., 2013, 2017; Campos-Rocha et al., 2022a, 2022b).

The second clade of the American Amaryllidoideae constitutes the tetraploid-derived (x = 23) Andean-centered tribes (Fig. 1). All, or at least some, members of each tribe have 2n = 46 chromosomes. The Andean clade is characterized by three consistent deletions, two in the ITS1 and one in the ITS2 regions (Meerow et al., 2000a), with the exception of Eustephieae Hutch. which lacks the indel in ITS2. The first branch of the clade is the tribe Eustephieae. The tribes Hymenocallideae Small and its sister tribe Clinantheae Meerow were recognized. A petiolate-leafed Andean subclade, containing elements of both Eucharideae Hutch. and Stenomesseae Traub (tribe Eucharideae) was also resolved. Interestingly, in both of the American subclades there is a small but diverse tribe that is sister to the rest of the group, the Eustephieae in the Andean clade, and the Griffinieae in the hippeastroid clade (Fig. 1). These two small tribes likely represent very isolated elements of their respective clades. Meerow (2010) concluded that the genus Pyrolirion Herb. was the first branch of the Eustephieae, rather than allied with Zephyranthes. Most recently, Meerow et al. (2020) performed a phylogenomic analysis of the clade and applied a curated suite of 524 nuclear genes and a partial plastome, which yielded well-supported, fully resolved trees, with much improved species resolution. All of Meerow et al. (2000)’s tribes were robustly supported as were most genera, and their generic composition is as follows: Clinantheae: Clinanthus Herb., Pamianthe Stapf, Paramongaia Velarde); Eucharideae: Eucrosia Ker Gawl., Phaedranassa Herb., Plagiolirion Baker, Rauhia Traub, Stenomesson Herb. and Urceolina Reichb. (including Eucharis Planch. & Lind., Caliphruria Herb. and Eucrosia dodsonii Meerow & Dehgan); Eustephieae: Chlidanthus Herb., Eustephia Cav., Hieronymiella Pax, Pyrolirion); and Hymenocallideae (Hymenocallis Salisb., Ismene Salisb., Leptochiton Sealy).

The Eustephieae, with a southerly bias in distribution, is always resolved as sister to the rest of the clade. The monotypic genus Androstephanos Fern.Casas, placed under synonomy of Hieronymiella argentina (Pax) Hunz. & S.C.Arroyo, appears more closely related to Eustephia with ITS sequences (unpubl. data). Clinantheae and Hymenocallideae are sister tribes, in turn sister to the Eucharideae (Fig. 1).

Unlike the Hippeastreae, the Andean clade does not appear to have experienced much reticulate evolution at the generic level (Meerow et al., 2020), but interspecific hybridization was evident within Hymenocallis especially, and within the rain forest understory subclade of the pseudo-petiolate leafed tribe Eucharideae. As a result, Traub’s (1971) transfer of Eucharis and Caliphruria into Urceolina was accepted (Meerow et al, 2020). Stenomesson is its sister genus. The Peruvian endemic Caliphruria korsakoffii was transferred into Stenomesson, and Eucrosia dodsonii to Urceolina (Meerow et al., 2023).

The Road Ahead

The past quarter century has resulted in the most resolute and accurate understanding of phylogenetic relationships in Amaiyllidaceae to date. However, despite such progress, there are still many questions that remain to be answered. Surprisingly, outside of García et al. (2017) and Meerow et al. (2020), there has been no other application of next generation DNA technology such as sequence capture using anchored hybrid enrichment, also known as Hyb-Seq (Cronn et al, 2012; Lemmon et al, 2012; Lemmon & Lemmon, 2013; Weitemier et al, 2014) applied to the family. Sassone et al. (2021) did apply genotyping by sequencing (GBS) to study the diversification of genus Ipheion in the Pampean region as well as to investigate the domestication history of Iphieon uniflorum (Graham) Raf. (Sassone et al., 2022). Hyb-Seq is clearly the future for developing more robust phylogenetic data sets at the species and generic levels.

There has been interest in whole plastome data recently (Cheng et al., 2022; Dennehy et al., 2021; Jimenez et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020). Whole plastome sequence data has been applied to recognize new species and estímate phylogeny in Lycoris (Lou et al, 2022; Zhang et al, 2021; Zhang et al., 2022) without any nuclear sequence data for tree comparison. There is frequently sizable cytonuclear discordance between phylogeny estimates from plastome versus nuclear data in the family (Marques et al., 2017; García et al., 2017; Meerow et al, 2020), which can at times signify reticulation. To that end, one must exercise some caution in formalizing taxonomic inferences from plastomes alone, without corresponding trees from the nuclear genome, especially in genera where hybridization has been documented.

Evolutionary development (evo-devo) compares the developmental processes of different organisms to infer how such evolved, using molecular data generally of candidate genes that are integral to developmental pathways (Goodman & Coughlin, 2000) or via transcriptome data (Roux et al., 2015). Very few evo-devo studies have been conducted in Amaryllidaceae (see Waters et al., 2013). Given the degree of canalized and convergent morphological characters in the family (Meerow, 2010), it is an approach that will hopefully see greater application in the future.

A final classification for the genera of tribes Gilliesiae and Leucocoryneae seems within reach, and just requires acceptance of only monophyletic genera, which will then require either taxonomic lumping or splitting.

The large genera Hippeastrum and Zephyranthes would benefit from a next generation sequencing approach combined with whole plastome sequences to unwind the obvious history of hybridization, aneuploidy and polyploidy. In the Andean clade, wider sampling within Eustephieae would be helpful. Among the Eurasian genera, the broadly distributed Pancratium is badly in need of a comprehensive revision as well as a well-sampled molecular phylogeny. New species have recently been described from India (Sasikala & Kumari, 2013; Sadasivaiah, 2018).

Many amaryllids are relatively rare in nature and may not flower every year. New exploration will undoubtedly continue to uncover new species. I look forward to seeing the next generation of systematists working on the family.

Fig. 1: Subfamilial and tribal level phylogeny of the Amaryllidaceae, based on García et al. 2014, 2017, 2019, 2022a), Meerow (2010), Meerow & Snijman (2006), Meerow et al. (1999, 2000a, b, 2006, 2020), and Sassone & Giussani (2018).

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork in South America was supported by USDA, and various National Science Foundation Deirdre Snijman at various times stimulated useful discussions on Amaryllidaceae. I am also grateful to the two reviewers of the manuscript, both of whom helped improve it.

Recibido: 27 Ene 2023

Aceptado: 7 Abr 2023

Publicado en línea: 30 Jul 2023

Publicado impreso: 30 Sep 2023

uBio

uBio