1. Introduction

This article aims to analyze the role of Russia’s foreign policy in an International Organization operating in Central Asia called the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Through the case study and a deductive methodology, as well as through the use of a descriptive quantitative tool, the main objective is to analyze whether Russia can project a strategic security leadership in Central Asia, through its participation in the SCO.

The strategic leadership addressed will be the concept used “as the ability to influence others to make, on a voluntary and routine basis, decisions that increase the long-term viability of the organization, while maintaining financial stability in the short term” (Rowe, 2002, p. 9-10). In addition, it can be characterized as: a) making decisions based on its own values; b) supervising short- and long-term activities; c) formulating strategies of immediate impact, as well as long-term goals; d) strategically controlling the financial scope; and e) using types of linear and non-linear thinking in the strategic decisions made (Rowe, 2002).

Therefore, the following question is posed: How does the Russian security agenda within the scope of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, between 2001 and 2018, reinforces a search for the country's strategic regional leadership in Central Asia?

The central hypothesis of the article suggests that the Russian Federation instrumentalizes the SCO's organizational apparatus for projecting power onto Central Asia, with the establishment of a political agenda on security in the region. As Russia acts as one of the leaders within the SCO and the organization's purpose is to maintain security for its members, there is a direct relationship between the Russian Federation, the promotion of security and its role in the organization at the international level.

As regards the bibliography analyzed in connection to the method and to address the proposed case study, we have used the approach proposed by Prodanov and Freitas (2013), Henriques, Leite and Teixeira Júnior (2015), Berg (2001) and Venesson (2008).

To study the case, we have carried out an analysis from the general to the specific, applying laws, principles or theories considered as truths to explain particular cases with a rational basis, in order to ascertain hypotheses. As rationality is one of the main objectives of this method, reason can lead to true knowledge as a science, that is, “Through a chain of reasoning in descending order, from analysis of the general to the particular, comes to a conclusion, ( ...) [and] uses the syllogism, the logical construction to, based on two premises, remove a third one (...), called the conclusion” (Prodanov & Freitas, 2013, p. 27).

It should be noted that the instrument used showed precision, as it conceived particular events in its methodological causal chain based on a more general principle, laws and theories. As it will be applied at the SCO, we looked at the causal chain that Russia applies to instrumentalize SCO as a regional projection in Central Asia. The following quote about this type of instrument summarizes its function well: “Case studies are essential to describe, categorize, generate typologies and hypotheses and, finally, explain manifestations of phenomena from the study of selected events, useful to launch [understanding] about a class of phenomena” (Henriques, Leite & Júnior, 2015, p. 13).

Case studies are used to evaluate theories, formulate hypotheses and explain particular events by causal constructions. The great challenge then would be to obtain, from the specific analysis, a generalizable knowledge that is related to other cases, since the phenomenon analyzed empirically would constitute a sample of major occurrences (Venesson, 2008; Berg, 2001).

For the proposed object, from the SCO, the aim was to verify –in practice– the use of the Organization by Russia as an instrument of power for regional projection in Central Asia. To do that, the paper is divided into two main sections: a) Shanghai Cooperation Organization: idea and conception in international security; and b) Russian geopolitics and Chinese trade: changing the balance of power in the SCO?

For the discussion of the balance of power, we will use Waltz’s concept. According to the author, balance of power “is a theory about the results produced by the uncoordinated actions of the states. Theory makes assumptions about the interests and motives of states, rather than explaining them. What it explains are the constraints that confine all states” (Waltz, 2002, p. 170).

Both the balance of power and the projection of strategic leadership are concepts that will complement one another in explaining the proposed object, since the interests of the Russian Federation (RF) will be observed as a constraint on the actions proposed by the State within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, in order to attain strategic leadership in the Central Asia region.

With this division, there is both a descriptive understanding of the SCO as well as an understanding of the geopolitical and economic dimension that the organization provides its members with, especially to the Russian Federation.

Among the main characteristics, what was taken into account since the conception of the SCO in 2001, with historical-descriptive detail, was the influence of neoeurasianism in Russian foreign policy inside the SCO, with the analysis expansion until 2018, to explain the delimited hypothesis and its causal relationship with the research object.

The time frame (2001-2018) was delimited because in 2001 the Shanghai Cooperation Organization was formally established and the organization's official data collection for the elaboration of the research extended until the year 2018.

2. Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Idea and Conception in International Security

With the dissolution of the former USSR, both Russia and the countries belonging to the former block had to adapt to the new international system that had taken shape after the United States defined a unipolar position in the system. Russia, now as a Federation and democratic regime, underwent domestic transformations that made it retreat politically from the international stage (Guimarães, 2016).

Aiming at a greater organization of its oriental international partners, as well as at maintaining their territory’s safety, still in 1996, Russia and China began to intensify a bilateral approach. This effort initially entailed a partnership that would promote a better definition of their borders and the promotion of mutual security (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007).

A year later, in 1997, together with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Russia and China advanced in the field of multilateral security and formed the group of the "Five of Shanghai", with the aim of entering into a series of bilateral agreements that promoted planning, trade and cooperation at the borders of the five countries involved. This stage became an action in relevant foreign policy which was set up in the next four years (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007).

It is noteworthy that this mutual interest between China and Russia, as well as the aforementioned Central Asian countries, led to the increasing engagement of the Sino-Russian bilateral relationship, which grew in parallel with the constitution of the Shanghai Five (Hashmi, 2019).

In their diplomatic history, since the end of the Cold War, Russia and China have signed more than 200 bilateral treaties, the most important of which was executed in 2001 and was called the Bilateral Treaty on Good Neighborhood and Friendly Cooperation, also known as the “Great Treaty” (Korolev, p. 5). This document stands out as being an important treaty of pact and non-aggression commitments by both parties, as it promotes defense between the two countries. This bilateral treaty served as a preparatory environment for the Sino-Russian relationship within the SCO shortly thereafter (Fels, 2018; Korolev, 2018; FMPRC, 2001).

Continuing the process of forming the SCO, in June 2001, with the addition of Uzbekistan, the creation of an International Organization was formally launched so as to promote the safety of the members involved and to seek lasting solutions to border issues, namely the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). With six members, the SCO arose out of a mutual need for cooperation between members, mainly Russia and China, even though they historically had divergent political thoughts (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007).

The SCO has a practical objective: the control of terrorism, separatism and extremism (mainly on religious grounds) in the geographic region of the member countries and they address these three issues as a priority on the organization's agenda, a fact that continues to the present day, as they can be seen in formal SCO documents released in 2018. Thus, the preservation of regional peace, security and stability is presented as the focal point of the organization (Ahmad, 2018; Hashmi, 2019).

Among the main objectives of the organization, there are also sub-themes that the SCO have paid attention to: the problem of illegal migration, drug trafficking, border problems between member countries and terrorism (Ahmad, 2018; Hashmi, 2019).

That said, in addition to security cooperation, the SCO aims at other areas, such as encouraging the collaboration of its members in the political, economic, commercial, scientific, cultural, technological, communication, educational and environmental spheres (Ahmad, 2018; Bailes, Dunay , Guang and Troitskiy, 2007). Nonetheless, despite the existence of diverse interests among SCO members, security remains the main focus of the organization's discussions. This is why this paper will highlight this particular aspect.

Regarding the economic sphere, on trade in energy products, the good Sino-Russian relations at SCO led to the development of SCO Inter Bank Association in 2005 and SCO Business Council in 2006, in order to “establish a comprehensive dialogue between SCO business circles on trade and investment issues” (RSPP, p. 1)

Regarding the promotion of security, the Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS) of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization was created in 2004. The formal creation of this center was relevant to develop a database within the SCO for the exchange of information and security services involving its members, for the promotion of peace in an analytical and scientific way (Ahmad, 2018; Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007).

In detail, the RATS promotes the “collection and analysis of information about terrorist organizations, information exchange (...), study of different forms of terrorism, monitoring of the counter-terrorist fight (...) and search for new approaches and campaign methods. anti-terrorism” (Ahmad, 2018, p. 123).

In terms of organization, the SCO has four levels, divided into the Council of Heads of State, Council of Heads of Government, Ministerial Meetings, and the Secretariat (this is divided into the General Secretariat and four other attached offices). In addition, the main agenda decisions at the SCO are made by consensus of member countries, which ends up bureaucratically clogging the organization. Below is an explanatory table with a more detailed description.

Source: Own elaboration based on Ahmad (2018), Yussupzhanovich and Tulkunovna (2019).

Figure 1 SCO Bureaucratic Structure

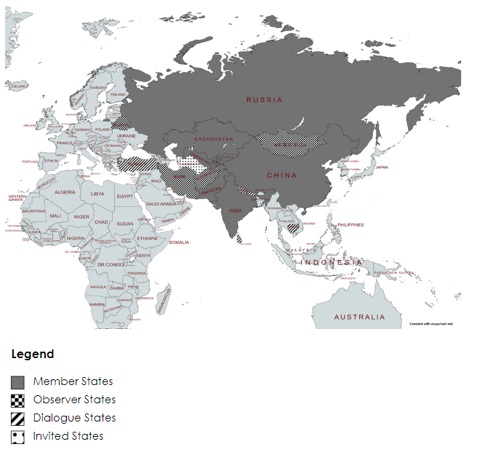

The initial stage of SCO, with only six main members, over the years posed some internal questions about which other States could become part of it. In fact, up until 2018 the SCO experiences some modifications in terms of observers, dialogue partners and guests (Fels, 2018).

The SCO has three states which, chronologically speaking, have become associated as observer members: Mongolia (2004), Iran (2005) and Afghanistan (2012). India and Pakistan have also been observers in the organization since 2005, but acquired the position of permanent members more recently in 2018 (Fels, 2018; Yussupzhanovich & Tulkunovna, 2019).

It should be noted that in 2005, in the same year that Iran, Pakistan and India gained entry to the SCO as observers, the United States was consensually denied their request. This measure to exclude the USA from the organization, not only in 2005, but also in later years, shows an anti-Western position within the SCO, shared by all members (Hashmi, 2019; Yussupzhanovich & Tulkunovna, 2019). This anti-Western sentiment will be further discussed in the last section, “Russian geopolitics and Chinese trade: a shift in the balance of power in the SCO?”

Regarding the dialogue between partners and guests, the first group has six countries: Cambodia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Turkey, while the guest is Turkmenistan, as formally convened in 2012.

A word needs to be added in connection with Turkmenistan. Shortly after the end of the USSR, this country obtained its independence, as did the other Central Asian countries. Since then and due to the turbulent history it experienced in its foreign policy during the Cold War, it was only in 1995 that the country declared to the United Nations a position of permanent neutrality vis-à-vis the international system. As such, the country has not aligned, since this declaration, with any regional block or military groupings, thus being it left out of several Asian organizations, such as the Collective Security Treaty or the SCO itself (Meshcheryakov, Shamgunov & Khruleva, 2019; Yapici , 2018).

Since then, China and Russia have attempted several bilateral attacks with Turkmenistan to gain their support in the area of security, as well as other political and economic areas (Yapici, 2018).

Comparatively, China had a greater success than Russia in approaching the government of Turkmenistan, mainly in three main moments: a) in 2004 with the creation of the Close Neighbor agreement for the promotion of security and greater bilateral approximation; b) in 2012 with the SCO's formal request that Turkmenistan be a 'guest' actor to participate in the meetings and; c) in 2013 with the Friendly Cooperation Agreement, already inserted in the bilateral commercial scope between China and Turkmenistan (Fels, 2018; (Meshcheryakov, Shamgunov & Khruleva, 2019; Yapici, 2018). Turkmenistan has taken its relationship with SCO in an inviting way, without much interest in becoming a full member so far.

The details of the geographic expansion of SCO with members, guests and observers are presented in map 1.

Source: Own elaboration, based on Bailes, Dunay, Guang e Troitskiy (2007), Yussupzhanovich e Tulkunovna (2019), by Mapchart settings.

Map 1 Geographical Extension SCO (2018)

Taking into consideration the SCO’s current span, it is understood that it extends from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok, as well as from the White Sea to the South China Sea. Furthermore, because of the size of the region, it is understood that the SCO collectively owns 17.5% of the world's proven oil reserves, as well as almost 50% of the natural gas reserves and about 45% of the world population, not including the Indian population, as this country only joined SCO in 2018 as a permanent member (Downs, 2018).

Turning our attention to the area of security, which remains a priority for SCO even after the addition of new members, it should be noted that several military exercises and peacekeeping missions by the organization have been organized and carried out since its creation. Among the most important are seven peacekeeping missions (2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2014, 2016 and 2018) and two military exercises of great impact, one in 2006 together with Tajikistan, due to the activities of terrorist groups in its territory, and one in 2016 involving Russia, Pakistan, Mongolia and India[1] (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007; Fels, 2018).

In view of this military situation, it is worth highlighting some main points involving the Sino-Russian relationship, the two countries with the greatest influence in SCO decision-making, as to security exercises and other areas of SCO cooperation.

Since the creation of the SCO in 2001, Russia and China have shared common mutual security interests, stemming from a reciprocal need for confidence in delimiting their borders and maintaining peace. However, it should be noted that outside this level of agenda with securitized themes, each country has other interests, which differ in comparison with each other's foreign policy (Ahmad, 2018).

Russia has a strong political interest in the SCO, mainly in the energy field, since Central Asia is a strategic region, because of its valuable natural resources and because it provides a favorable market to the Russians in the export of oil and its derivatives. In this case, the search for strategic leadership in the region is of paramount importance for its political purposes, with the western involvement in this process as an exclusionary position (Fels, 2018).

China, being a world economic and commercial power, is more interested in improving the infrastructure that Central Asia can provide for the SCO in its trade routes. With a gigantic project to define the new Silk Road[2] in the 21st century, called OBOR (One Belt, One Road), from 2014 to 2017 China obtained an investment of more than US $ 110 billion and aims to build roads that connect China to Europe, passing through Central Asia. In addition, it intends to have a direct link with Southeast Asia, North Africa and the Gulf countries (Fels, 2018; Yussupzhanovich & Tulkunovna, 2019).

As shown in the figure above, the OBOR project extends through both land and sea, going through Central and South Asia, Europe, the Middle East, as well as the Indian and Mediterranean seas, with a total of sixty-four countries involved (Kettunen, 2018).

The following may help to fully understand the grandeur of the Chinese project in its geographic expansion:

The OBOR initiative was launched in late 2013 to develop infrastructure for new trade routes. These include the “Silk Road Economic Belt”, connecting China by rail with Central Asia, Europe and the Middle East, and the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” to develop sea routes from coastal China to the Indian Ocean and to the Mediterranean (...). As part of China's global economic strategy, OBOR's geographic scope is ambitious, with 64 countries participating in the plan in Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia. (Kettunen, 2018, pp 121-122)

In view of the foregoing, to better understand the main characteristics of the SCO discussed, involving the associated countries, treaties carried out, Sino-Russian interests and military exercises / peacekeeping missions carried out, we have included a timeline with the events associated with the Organization.

Source: Own elaboration based on Ahmad (2018), Bailes, Dunay, Guang and Troitskiy (2007), Yussupzhanovich and Tulkunovna, (2019), Hashmi (2019), Downs (2018), Korolev (2018), Russian (2018).

Figure 3 SCO’s Timeline (1996-2018)

Upon analyzing the previous figure, we can see how much the SCO has developed as an institution since its birth in 2001. Military advances among member countries, basically in the last decade, have not exceeded the margin of two years. In addition, formal contacts and increased cooperation are constantly taking place in other areas of interest that the international organization provides, such as energy and commercial development.

The peace operations carried out by the SCO also present a regional balance of power, as there is a security constraint in demonstrating military strength at the borders and / or in the vicinity of its member countries. Thus, because Russia is present in most of the military apparatus used, there is a projection of security leadership by the Russians in the performance of the international organization.

Due to the new forms of cooperation that the SCO has been opening up, there is a question as to whether it is right to say that the organization has already overcome the barriers of military alliance / cooperation to develop other areas. Thus, it is worth arguing here about the institutional stages that the SCO provides in the military sphere, involving the moderate or advanced level.

Korolev (2018) points out eight main points to identify whether an institution is moderate or advanced in the military sphere. To be considered moderate, it must have five main elements, namely: a) Treaty or alliance agreement; b) Mechanism for regular consultations; c) Technical Military Cooperation and exchange of persons from the armed forces; d) Regular military exercises; and e) Confidence-building measures (Korolev, 2018).

At the level of advanced institutionalization, there are three more characteristics, namely: a) Integrated military command; b) Placement of joint troops and / or exchange of military bases; and c) Common defense policy (Korolev, 2018).

Applying the characteristics highlighted to the SCO, the following result is achieved.

Analyzing the previous table, it is identified that the SCO is currently in a moderate degree of military institutionalization, but moving towards an advanced position, since the characteristic "integrated military command" already exists.

It is noteworthy that this military integration of the SCO, the first step towards an advanced institutionalization, occurs because of the “increasing scope and regularity of military interactions [between] China-Russia, [with] an integrated military command (...). According to some evaluations, there is a modest degree of compatibility and interoperability between Chinese and Russian forces” (Koroloev, 2018, p. 14), directly influencing this relationship within the SCO (Korolev, 2018).

This security and, consequently, military development process has given rise to a series of common problems that the SCO member countries share with each other. More than the desire to expand cooperation within the SCO to other areas of interest, a common denominator remains on the organization's agenda, which are the new threats still associated with the security area (Ahmad, 2018).

More than the delimitation and pacification of the borders of the member countries, initial interest for the emergence of the SCO between Russia, China, the countries of Central Asia and now also India and Pakistan, terrorism, separatism, extremism, drug trafficking and illegal migration are examples that remain on the agenda in the SCO's formal dialogues and actions, that is, in the security sphere (Bailes, Dunay, Guang and Troitskiy, 2007; Russo, 2018).

In the next section, these security problems will be dealt with more comprehensively.

3. Russian Geopolitics and Chinese Trade: a Shift in the Balance of Power at SCO?

Since its creation the SCO has been used as a point of convergence of interests among its members and, due to its relevance in the International System, Russia and China share the power balance inside the organization.

Even though this convergence of interests exists, mainly in the area of security, Russia and China also have their own, both directed to Central Asia and the SCO, which leads to a different discussion involving other issues, such as the particular Sino-Russian agenda. For the Russian Federation, the focus is on a position with a more traditional security policy aspect, with military strengthening and regional stability in this area, gaining greater influence in the Central Asia region and excluding any Western participation. It is in this aspect that Russia invests in regional strategic leadership (Fels, 2018).

In addition, as the Russian role in the SCO has considerable political relevance and weight, the other members with lesser projection within the organization follow the Russian security directive, whether to guarantee their own security, to maintain regional stability or even state survival.

This can be seen in the need for border stability that SCO permanent members have, Russia’s historical role in regions that were previously influenced by the USSR, and the maintenance of energy trade routes which Russians have attendance, such as the Caucasus region, gas pipelines crossing Ukraine and parts of Central Asia that connect Sino-Russian trade relations (Adam, 2013; Haas, 2010).

According to the strategic leadership concept, “the ability to influence others to make, on a voluntary and routine basis, decisions that increase the long-term viability of the organization, while maintaining financial stability in the short term” (Glenn Rowe, 2002, p. 9-10), Central Asian countries end up following the Sino-Russian decisions in order to guarantee the characteristics that the strategic leadership concept presents to them (Glenn Rowe, 2002).

For China, on the other hand, the focus is on building a more robust infrastructure that facilitates its commercial exchanges and strategic partnerships, to further expand its economy. To this end, it also wants to limit Western influence as regards its commercial interests, which directly associates China with the Russian position in this regard, even though they are different areas of discussion (Russian security policy and Chinese commercial policy) (Yussupzhanovich & Tulkunovna, 2019).

From 2001 to 2018, much was discussed at the SCO, despite maintaining its focus on security, and the expansion to other areas of cooperation has been happening gradually, which has given more advantages to the Russian and Chinese interests so as to share and gain visibility on different issues, changing the power balance inside the organization (He & Feng, 2019).

It is not surprising that China seeks so much commercial expansion and gains an advantage in the International System, because this has been the country's stance since the end of the 20th century. The OBOR project, with the new silk route, mirrors this Chinese strategy (Yussupzhanovich & Tulkunovna, 2019).

In strategic observation of the Chinese trade agenda, Russia invested in a good relationship with the country to take advantage of the growth of the energy market and shape its policy towards Central Asia (Gabuev, 2018; Lo, 2020).

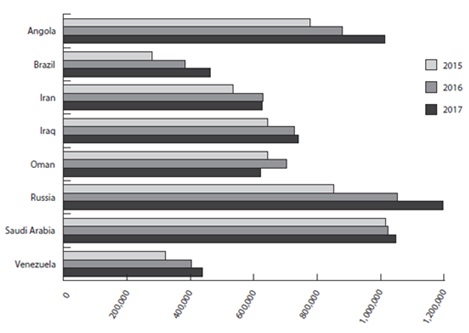

Based on the Putin administration, several Sino-Russian bilateral agreements and joint actions within the SCO, in relation to the trade in oil and its derivatives, resulted in a significant increase in commodity exports between 2008 and 2017. The Russian Federation increased its export to China from 234 thousand barrels of oil to 1.2 million in 2017, even surpassing Saudi Arabia in 2016 and 2017, as can be seen below (Downs, 2018).

When expanding the variable for fossil fuels and minerals in general, we can observe between 2015 and 2017 a significant increase in bilateral Sino-Russian energy trade, with a variation of 35.86% (World Trade Organization, 2019).

Source: Own elaboration, based on World Trade Organization (2019).

Graph 1 Chinese bilateral trade - Import of fossil fuel and mineral products (Bi US$)

In 2015, Saudi Arabia was gradually decreasing, at the same time as the good Sino-Russian relation was advancing. Comparing to the import variation, Saudi Arabia had an increase of only 1.01%, much lower than Russia’s 35.86% increase.

It is worth highlighting that the increase is well above average in relation to Australia. As a result of an FTA (Free Trade Agreement), China and Australia signed an agreement called ChAFTA (China-Australia Free Trade Agreement), conceived in 2014, but executed in 2015, which established free taxes around 93% of Australian products. Such bilateral easy had a powerful effect, resulting in a positive variation of 110.85% (Yan, 2019; Culas & Timsina, 2019).

In total exports, involving all Russian products to China, according to Fels (2018), from 1995 to 2015, there was an increase from US $ 4.2 billion to US $ 63.5 billion. In Chinese government figures, the variation over the same period was greater, from $ 5.5 billion to $ 68 billion (Fels, 2018).

Regardless of the commercial product analyzed, the good Sino-Russian relationship is visible and, as Russia is strong in the trade of energy products, it ends up investing better in this segment (Hashmi, 2019).

This mutual support between Russia and China ends up resulting in the execution of each individual's agenda, both in Russian security policies and in Chinese trade. A practical example of this was when Russia invaded Crimea in 2014 (Downs, 2018). As a consequence of this invasion, the West has implemented several economic sanctions against Russia, resulting in the country's uncontrolled domestic inflation. In this economically unfavorable scenario, China initially took a neutral stance in the face of this conflicting Russian stalemate, but soon afterwards saw an opportunity to diversify the market, focusing on Asia. There was an increase in Sino-Russian trade and it gave the Russian Federation an economic relief from the sanctions had brought that year (Downs, 2018; Yingyi, Mikhailovna, 2018)

The Sino-Russian partnership to replace Western capital created an opportunity to develop an economic lifeline for the Chinese and rekindled the Russian energy market, promoting multiple national interests in both countries (Yanéz, 2019). Besides the opportunity for commercial diversification in the East, Russia and China also saw in practice the importance of distancing Western influence (USA and European Union) from their subjects of interest. As a result, the presence of Neo-Eurasian theory in Russian policy has become increasingly present, guiding its foreign policy and influencing the SCO in security policies (Yanéz, 2019; Fels, 2018).

The anti-Atlanticism that neo-Eurasianism shows itself, at least in the expansionist geopolitical view and the alignment of the Sino-Russian agenda inside SCO, presents some important characteristics for discussion.

Russia wants to maintain its leadership in the energy market and in the definition of security policies in the SCO and Central Asia, while the Chinese are looking for another more ambitious aspect with the OBOR project. As the main objective of the SCO is to focus on security and not on trade, the change in Chinese focus within the organization is giving way to a more active Russian position in this area (He & Feng, 2019).

Even though they have different interests, there is a mutual and coherent alignment between the two countries. There is a certain type of tacit agreement between the Russian Federation and China, in which the Russians maintain their centralized strategic leadership in the political and security spheres in Central Asia, while China takes the lead in commercial and economic progress in the region (Gabuev, 2018; He & Feng, 2019).

In this aspect of dividing influences, it is possible that “a reduction in China's role of [being more] active in the SCO would encourage Russia to try to increase its influence within the SCO space and give it the character of a geopolitical organization, defending anti-Western positions” (Yussupzhanovich & Tulkunovna, p. 53, 2019).

With major Russian participation in the SCO, the power balance would bend in its favor, seeing that the Chinese interests are focused on the OBOR project and the expansion of its market. In this case the RF is centered on the regional policy, security and stability from Central Asia.

Specifically in this relationship between China and the OBOR project, after the 2008 crisis, the Chinese observed a huge deficit in the infrastructure of Asian trade routes, both on land, as well as in sea and aeronautics. In a projection between 2010 and 2020, a report released by the Asian Development Bank pointed out that the sum of US$ 8 trillion dollars was necessary for the readjustment of the OBOR project and its execution (Vadell, Secches & Burger, 2019).

In this context, it can be observed that the global economic hegemony operates in a multipolar way, in a contemporary globalization called “deglobalization”, since China, after the crisis of 2008, has increasingly taken away from the United States the position of global economic, as well as commercial and financial, leader. That said, the OBOR project is the great Chinese move in a contemporary neoliberal countermovement (Vadell, Secches & Burger, 2019).

Therefore, turning our attention to the Russian Federation, some characteristics of why Central Asia is a strategic region, in its geopolitics and in the maintenance of security, are worth highlighting below.

To the Russians, Central Asia is understood as a strategic extension of the homeland itself, since Russian is the second most spoken language in the region (approximately five million ethnic Russians) and there is a close cultural proximity. In addition, the region is the only remainder, in comparison to the time of the USSR, that Russia is able to operate without direct interference from the west, that is, without the control of the European Union or NATO (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007).

For this Russian presence to last, security stability in the region is necessary, as discussed so far, as well as the collaboration of the countries of Central Asia and China in maintaining it. Thus, there is a cooperative and non-provocative attitude among SCO members in their relationship with Russia, maintaining the Russian status quo and active presence in the region (Gabuev, 2018; Lo, 2020).

With this ease of Russian action, the Russian Federation was able to implement its security policy in the Central Asian region, having the freedom to use military facilities and play an active role in its foreign policy. In this way, with the greater space in this aspect that China offers to the Russians, the strengthening of the anti-Westernism/anti-Atlanticism of Neoeurasianism is increasingly present, both in Central Asia and in the SCO itself (Balls, Dunay, Guang and Troitskiy, 2007; Dugin, 2014, 2016; Lo, 2020).

It is important to emphasize that, in addition to the SCO, Russia has other international players that give strength to its activities in Central Asia, as is the case of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), reinforcing its neo-Eurasian position in security area (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007).

With this division of interests, we can see the development of two types of strategic leadership operating in Central Asia: Russia, which is focused on the political-security sphere, and China, which is linked to trade. This separation of strategic directions follows two types of decision makers, the decision maker and the decision taker (Shaxson, 2005; Pion-Berlin & Arcenaux, 2000).

The decision maker is the one who creates the political scenario and presents the possibilities of direction, offering possibilities for action. The decision taker, on the other hand, visualizes the possibilities offered by the decision maker, chooses what suits its interests and incorporates it into its policy (Shaxson, 2005; Pion-Berlin & Arcenaux, 2000).

Applying this understanding to the Sino-Russian relationship and SCO participation, China would be the decision maker, while Russia would be the decision taker. China, as a power in the International System, has a greater weight than Russia in the economic sphere, behind only the United States (Gabuev, 2018; Lo, 2020). Therefore, with the intention of intensifying the Asian market in its favor, Central Asia enters the process as a strategic region to achieve this end, as discussed by the OBOR project. Russia, which is also a powerhouse, but its weight lies in the International System on security and military aspects, ends up losing space in the trade race with the Chinese (Gabuev, 2018; Lo, 2020; Fels, 2018).

However, as it is important for the Chinese to have regional stability, in which security plays a significant role in reaching their commercial interest, it is a good trade-off with the Russians to cede this type of security leadership in Central Asia to the Russian Federation, with the SCO as an active formal organization. Consequently, the Chinese commercial advantage also brings benefits to Russia, with the export of military products and energy trade (Bailes, Dunay, Guang & Troitskiy, 2007; Hashmi, 2019).

Regarding the military market, specifically, we can see China's efforts to reduce its dependence on Russian products in this segment, as it has developed its national armaments industry, as can be seen in the graph below. However, even with this commercial retraction under the Russian eye, this is still a market of interest to Russia (Gabuev, 2018; Lo, 2020).

Source: Own elaboration, based on SIPRI (2019).

Graph 2 Major investors in military expenditures from SCO member countries

In the 2010s China turned to the national arms market, leaving Russia in the background. As a result, there was a sharp drop in Russian exports to the country in this commercial niche. As a consequence, Russia has given greater focus to its energy market with exports to China, overtaking Saudi Arabia and becoming the main Chinese partner in fossil fuel and mineral products (Downs, 2018)

In short, there is a parallel of strategic leaderships involving Russia and China, one from the commercial side and the other from security policy. Even though Russia is in a position of decision taker, it manages to project a strategic security leadership in Central Asia, instrumentalized via the SCO, as can be seen in the explanatory table below.

Source: Own elaboration, based on Gabuev (2018), Lo (2020), Ahmad (2018) and Fels (2018).

Figure 5 Russian and Chinese Strategic Leadership in Central AsiaRFP (Russian Foreign Policy); SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organization); OBOR (One Belt One Road).

As can be seen above, the Chinese decision maker position unleashes a series of elements associated with Russia that result in its decision taker position. Even hierarchically below the influence of China in the International System, Russia is able to project itself into a strategic leadership in security policies, and in parallel to the Chinese strategic leadership in the commercial sphere.

In order for Russia to keep its role in security policies, the good diplomacy with China and the trade partnerships established with it constitute important factors. The weapon and energy markets stand out. Being China’s main partner provides Russia with more investment in its security agenda and towards its foreign policy from a neoeurasian perspective (Lo, 2020; Ahmad, 2018; Fels, 2018).

Consequently, this entire process is instrumentalized via the SCO, since the main objective of the organization is in the security segment involving its members. As China is currently focused on expanding its trade with the new silk route through the OBOR project, it opens up a direct space for the Russian Federation to act on its strategic leadership projection in Central Asia, aligning its neo-Eurasian-influenced foreign policy agenda to the SCO.

In this way, the expansionist neo-Eurasianist current is explored in Russian foreign policy directly via the SCO, that is, as an expansion of Russian anti-Western thought in the Central Asian region and also as an influence on the other members of the organization. Despite being a decision taker, Russia manages to project itself into a strategic leadership role in the field of security, gaining more influence in this area of strategic geopolitical interest to the Russians.

Finally, the SCO's power balance in favor of the Russian Federation means that its own security policies are inserted by the organization. In the new International System, where there is a plurality of international actors, having a formal organization that contributes in an assisted way to Russia's foreign security policy actions is logical and in line with contemporary reasoning in the Central Asian regional political game, even though the RF is a decision taker.

4. Conclusions

The good bilateral relationship between Russians and Chinese has led to the development of international mutual cooperation projects, as discussed in the case of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and its creation in 2001. With a focus on security, the Sino-Russian relationship is predominant, even if there are different interests involving other business characteristics, outside the scope of security itself.

About the OBOR project, China intends to expand the old silk route with investments that already exceed US $ 100 billion. For its project to continue, it is of paramount importance to maintain security stability in Central Asia, a strategic region not only geographically for OBOR's infrastructure to work, but also because it is rich in energy products.

Both China and Russia are looking for regional strategic leadership, but at different levels. Through the OBOR project, it appears that the Chinese are increasingly interested in economic development, while the Russians in maintaining security policies.

In the International System, China has a greater weight, compared to the Russians, which makes it a decision maker, while the Russian Federation assumes the role of decision taker. However, even though this differentiation exists between the two actors, there is a projection of the leadership positions of both.

Analyzing this Sino-Russian stance in connection with the concept of strategic leadership, it has been shown that both countries have the capacity to influence political decisions that make their interests viable in the long term, whether in the economic or security spheres. Therefore, the projection of leadership takes place in a systematic and strategic way, respecting their zones of influence.

Specifically in Central Asia, China is able to exercise strategic leadership in the commercial sphere, while Russia exercises it in security policies. It is interesting to note that China projects its regional leadership in Central Asia due to the commercial strength it has worldwide, setting aside its influence on security, that is, its participation in the SCO is on a smaller scale.

However, the Russian Federation is investing more and more in security policies, as well as greater military action in Central Asia, instrumentalized by the SCO, leaving the country in greater evidence in the organization.

There is an interesting Sino-Russian exchange among leaders, between the decision maker and the decision taker. China giving the Russians more advantage to act inside SCO, RF consequently manages its own security agenda in the organization, thus achieving a greater projection of strategic leadership in security, as well as leaving the SCO power balance to its own favor.

Even though China is politically aware of this Russian engagement in the security sphere, it is a beneficial to the country to achieve this stability in Central Asia in order to develop its trade project.

Therefore, for the research question proposed in the present work, the Russian instrumentalization via the SCO and projection of its strategic leadership in Central Asia occurs in the scope of security, due to the good diplomatic and economic relationship they have with the Chinese, especially after 2001 with the Sino-Russian Friendship Treaty and the formation of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization itself. In other words, the good relationship between the decision maker and the decision taker means that the two powers are able to strategically project their leaderships, whether in the economy or in security.

In view of this regional scenario, it is clear that the Russian Federation took control again of its international decisions in the 21st century, dealing with a pragmatic foreign policy between economic investment, under a strong and centralizing state.

With the control of domestic privatizations and political decisions in the country, as well as less Western foreign dependence, Putin was able to act in the International System as a relevant actor in his topics of interest, influenced by Duginist neoeurasianism. In the case of Central Asia, Russia’s anti-Western position vis-à-vis the United States and the European Union, with the support of the SCO and its members, is incisive.

Finally, confirming the tendency of the power balance in its favor in the organization, due to reduced Chinese participation in the SCO, Russia advances in its expansionist geopolitical neo-Eurasianist, while defending multilateralism and anti-Atlanticism and guaranteeing its influence in the “Russia-Eurasian Big Space" in the counter-strategy movement of American unipolar globalization.

It is also important to note that the good relationship with the Chinese, as well as the addition of India and Pakistan to the SCO, results in the expansion of Russian influence in three more regions of Dugin's expansionist neoeurasianism (2014, 2016), which Dugin names as the “Great Islamic Continent Space", "Islamic Continent Space Grid" and "Great Chinese Space" (Dugin, 2014, 2016).

![Bilateralismo preponderante entre Estados Unidos y China durante 2019-2021 []](/img/pt/prev.gif)