Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina

Print version ISSN 0004-4822On-line version ISSN 1851-8249

Rev. Asoc. Geol. Argent. vol.60 no.1 Buenos Aires Jan./Mar. 2005

Dynamic paleogeography of the Jurassic Andean Basin: pattern of transgression and localisation of main straits through the magmatic arc

Vicente, J-C.

Laboratoire de Tectonique, Université P. & M. Curie-Paris 6. Case 129, F 75252 PARIS Cedex 05, France. E-mail: vicente@lgs.jussieu.fr

RESUMEN

Paleogeografía dinámica de la cuenca jurásica andina: diseño de la transgresión y localización de los principales estrechos a través del arco magmático. La evolución paleogeográfica de la cuenca de retroarco andina jurásica es examinada a escala global en los Andes Centrales. En este trabajo, se llama la atención sobre la continuidad y la persistencia del arco volcánico activo. Evidencias sedimentológicas, tanto directas como indirectas permiten localizar el borde occidental (insular) de la cuenca opuesto al borde oriental (cratónico). Un énfasis especial es puesto en los depósitos volcaniclásticos y estructuras sinsedimentarias asociadas con este borde insular. Se concluye que la actividad del arco magmático ha contribuido considerablemente en el suministro de sedimentos a la cuenca. La extensión y continuidad del arco permite ubicar los estrechos que conectaban con el Paleopacífico. Una verificación sistemática de la edad de las transgresiones acoplada con un análisis de facies secuencial provee una perspectiva dinámica del proceso transgresivo. Los sectores con una ingresión temprana permitieron distinguir dos golfos principales del pasaje a través del arco, en los cuales el mar avanzó longitudinalmente al mismo tiempo tanto hacia el norte como al sur, en un surco profundo de retroarco: el primero a la latitud de Taltal (25°S), y el segundo a la latitud de Curepto (35°S). Ambos se iniciaron en el Triásico y se extendieron durante el Hettangiano. La evolución como cuencas separadas (Tarapacá and Aconcagua-Neuquén) finalizó con la fusión en el Pliensbaquiano medio dando lugar a una cuenca continua y alongada desde el Chubut hasta el norte de Perú. La remarcable continuidad y lo angosto de la cuenca andina no deja dudas de su control tectónico. Esto configura su ambiente geotectónico como una típica cuenca de retroarco adyacente a un arco magmático muy activo y explica la extrema movilidad de su margen insular caracterizado por una enorme ola volcaniclástica con flujos de detritos y turbiditas asociadas.

Palabras clave: Cuenca andina. Jurásico. Arco volcánico. Paleogeografía. Margen insular. Retroarco.

ABSTRACT

The paleogeographic evolution of the Jurassic Andean retroarc basin is examined at a global scale for the Central Andes. In this paper, it is called for the striking continuity and lasting of the active volcanic arc. Both direct and indirect sedimentologic evidences allow to locate the western border (insular) of the basin and opposite it with the eastern border (cratonic). Emphasis is placed on the volcaniclastic deposits and synsedimentary structures associated with this insular border. It is concluded that the arc magmatic activity has contributed considerably in sediment supply to the basin. Extent and continuity of the arc implies to locate the straits connecting with the Paleopacific. Systematic check of the time of transgressions coupled with sequential facies analysis provides a dynamic outlook of the transgressive process. Sectors with early transgression allow to distinguish two main gulfs of passage through the arc from which waters have progressed lengthwise at the same time northward and southward in a narrow retroarc furrow : the first at latitude of Taltal (25°S), the second at latitude of Curepto (35°S). Both initiated in the upper Triassic and extended during the Hettangian. The evolution as separate basins (Tarapacá and Aconcagua-Neuquén) ended by fusion in middle Pliensbachian giving rise to a continuous elongated basin from Chubut to northern Peru. The remarkable continuity and narrowness of the Andean Basin leaves no doubt about its tectonic control. This stems to its geotectonic setting as a typical retroarc basin adjacent to a very active magmatic arc and explains the extreme mobility of its insular margin characterized by a huge volcanoclastic apron with associated debris flows and turbidites.

Key words: Andean basin. Jurassic. Volcanic arc. Paleogeography. Insular margin. Retroarc.

Introduction

Critical analyses of recent paleogeographic maps of the Neuquén Basin marine Jurassic (Riccardi 1983, Rosenfeld 1983, Gulisano 1992, Legarreta and Uliana 1996) show large differences between the known eastern (cratonic) and western (insular) margins. Whilst the eastern margin is rather well delineated through time, the western margin remains uncertain and variable according to different authors. Maps usually show a basin open to the west where communication with the Pacific Ocean is barely interrupted locally by the Jurassic volcanism of the Chilean Coastal Cordillera (see Riccardi 1983, fig. 12), But, following ideas anticipated by Chotin (1976) and laid out by Digregorio et al. (1984), the basin is given a retroarc position. The only map depicting a western border of the basin was published by Riccardi and Gulisano (1990, their fig. 2), based on the present-day distribution of marine Jurassic (Araucanian Synthem), it has no paleogeographic implications.

In our opinion, all these schemes diminish the importance of the volcanic arc that during the Jurassic limited the basin on the west. However, the concept of a Marianas-type arcbackarc system characterising the active western margin of the South American continent, has been widely accepted due to the studies of Coira et al. (1982), Davidson (1984), Mpodozis (1984), and Mpodozis and Ramos (1990). The first paleogeographic sketch map considering a well defined magmatic arc-retroarc basin pair is that of Hallam et al. (1986) but his was for the Tithonian. In fact, the only maps picturing genuine continuity of the volcanic arc along the entire Andean margin during the Jurassic are those of Zambrano (1987, his fig. 2), Urien et al. (1995, their fig. 5) and Pindell and Tabbut (1995, their fig. 1 and 2). At regional level must be mentioned the facies assemblage map presented by Prinz (1986, his fig. 2) for the Bajocian by latitude 21°-25°S of the chilean Norte Grande. There is also the indefinite representation by Legarreta and Uliana (1996, their fig. 9c) in their paleogeographic reconstruction for Pliensbachian-Lower Toarcian of pyroclastic and volcanics west of Neuquén Basin at the frontier with Chile by latitudes 38°-39°S.

This is due to three main reasons:

1) Accessibility: The succession showing the relationship between the Chilean volcanic and the Argentinean sedimentary series south of 33ºS, is located along the Principal Cordillera frontier, i.e., in the highest area with the most difficult access.

2) Tectonic: As a result of the detachment of the Andean series of the external fold and thrust belt at the level of the Oxfordian gypsum (Vicente 1972; Cristallini 1996), the pre- Oxfordian Jurassic is underrepresented towards the west. Exceptions are some Callovian-Oxfordian tectonic sheets found at the base of some gypsiferous diapirs (Gonzalez 1963, Thiele 1980,Vicente, 1972, Ramos 1985 a, b, Godoy 1993, Ramos et al., 1993, Alvarez 1996 a, b, c, Alvarez et al. 1996, Pangaro et al. 1996, Buhler et al. 1996) or related to some basement highs on which the Jurassic has been preserved (e.g. Cordillera del Viento, Portezuelo Ancho). Furthermore, within the Andean belt, the Argentine-Chilean boundary region is characterised by the Chilean volcanic succession overthrusting towards the east the Argentinean sedimentary succession. Due to this "Major Andean overthrusting" (Vicente 1970, 1972, 1993 and 1998) most of the western half of the retroarc Andean Basin is tectonically overprinted.

3) Stratigraphy: On the Cordilleran Chilean slope, the Andean successions are unconformably covered, towards the west and up to the coast, by the thick Upper Cretaceous (Viñita Formation), Tertiary (Abanico Formation) and Miocene (Farellones Formation) volcanogenic successions that form the so called "Andean synclinorium".

In spite of these limitations, the boundary region south of 33ºS seems to be a key area to solve problems of paleogeographic and tectonic relationships between the Chilean and Argentinean successions. Further north, the obliquity of the Jurassic paleogeography (NNW-SSE) with respect to the present day morphostructural directions (N-S), places the transitional zone within the Chilean slope, where, due to the basement folds, the Jurassic is exposed in several belts, offering additional solutions to those found in the southern region.

The aim of this paper is to analyse the facies at the boundary between Argentina and Chile, together with the longitudinal changes in age of transgressions and regressions. Recognition of the relative continuity of the Jurassic volcanic arc, location of some major straits through it and typification of the transgressive and regressive patterns will improve our knowledge of the Andean Basin dynamic.

The starting point of this study is our detailed unpublished analysis of the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza between latitudes 31°30' and 33°00'S (Fig. 1, 2 and 3a, b), where important east-west facies changes are evident (Fig. 4) within a relatively complex tectonics. This has made us aware of the limitations of the lithostratigraphic nomenclature of the Neuquén Basin and the preference of using instead ages and facies sequences (Vicente 1975). That is why in the following we will speak quite exclusively of facies and ages and will mention formations just for information. As I think, the complexity of regional stratigraphic nomenclature does not contribute to clarify the topic and often has a chronostratigraphic overtone that may be harmful for the characterization of diachronous events. So that, we refer those interested by more details on lithostratigraphy to the Riccardi and Damborenea (1993)'s Jurassic Stratigraphic Lexicon of Argentine and also the updated Legarreta and Uliana (1999)'s Chronostratigraphic Jurassic Charts for the Main Cordillera and Neuquén Basin.

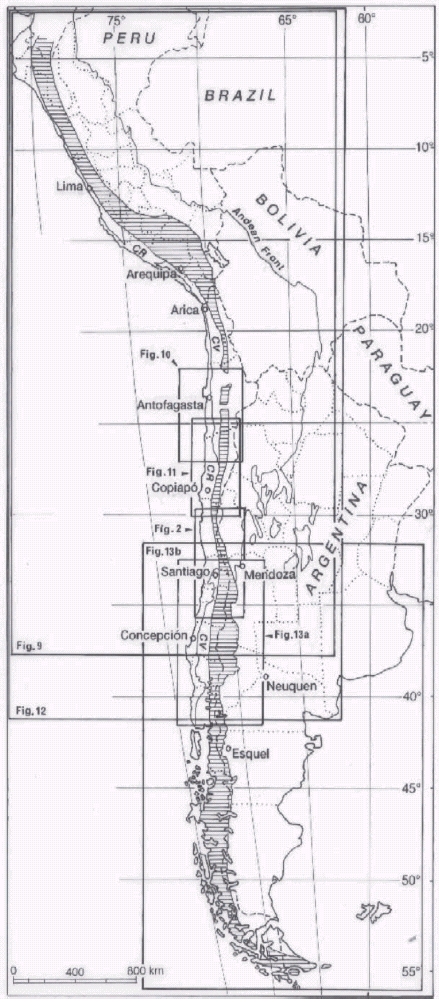

Figure 1: Locality map showing main Andean morphostructural units of interest and areas covered by paleogeographic maps included in this paper. Distinctive Main Cordillera (= Principal or Western Cordillera) is hachured; CR= Coast Range; CV= Central Valley; Limits of Provinces (=Departments or Regions) of Argentine, Chile and Peru are also indicated.

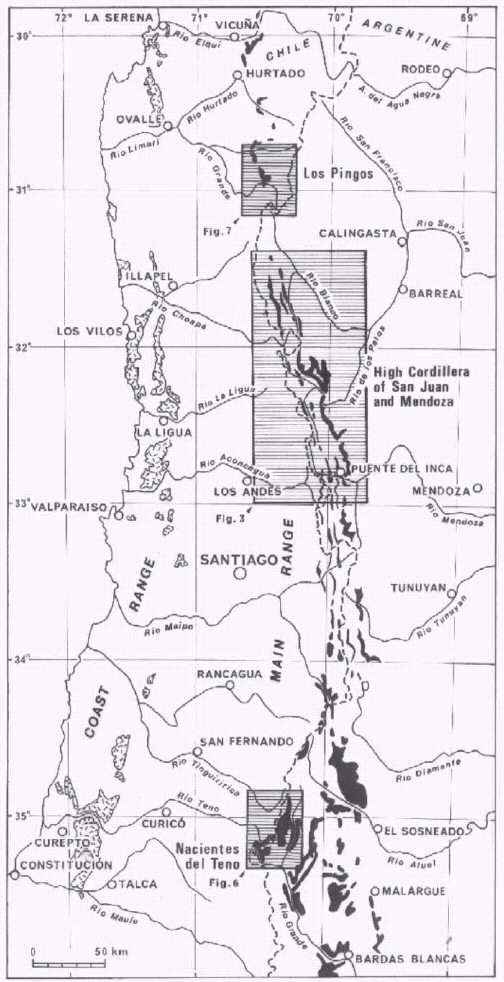

Figure 2: Distribution of marine Jurassic outcrops of the Andean Basin between latitudes 30° and 36°S and location of the study area of the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza as well as the complementatry areas of Los Pingos and Nacientes del Teno. A special pattern is used for the complementary volcanic and volcanogenic outcrops of the Coast Range which include moreover Upper Triassic series.

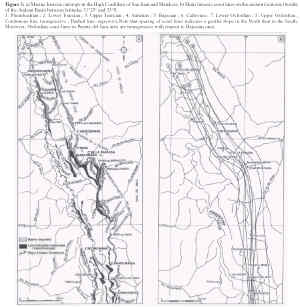

Figure 3: a) Marine Jurassic outcrops in the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza; b) Main Jurassic coast lines on the eastern (cratonic) border of the Andean Basin between latitudes 31°25' and 33°S. 1: Pliensbachian; 2: Lower Toarcian; 3: Upper Toarcian; 4: Aalenian; 5: Bajocian; 6: Callovian; 7: Lower Oxfordian; 8: Upper Oxfordian; Continuous line: transgressive; Dashed line: regressive. Note that spacing of coast lines indicates a gentler slope in the North than in the South. Moreover, Oxfordian coast lines in Puente del Inca area are transgressive with respect to Bajocian ones.

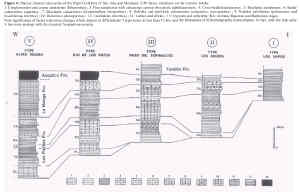

Figure 4: Marine Jurassic type-series of the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza: E-W facies variations on the cratonic border. 1: Conglomerates and coarse sandstones (litharenites); 3: Fine sandstones with calcareous cement (bioclastic sublitharenites); 4: Cross-bedded sandstones; 5: Bioclastic sandstones; 6: Sandy calcarenites (sparites); 7: Bioclastic calcarenites (biosparudites, biosparites); 8: Oolithic and pisolithic calcarenites (oosparites, oncosparites); 9: Nodular calcilutites (pelmicrites and fossiliferous micrites); 10: Dolomites (dolosparites); 11: Calcilutites (micrites); 12: Lutites and siltites; 13: Gypsum and anhydrite; BA: includes Bajocian and Bathonian stages. Note significance of facies transverse changes which impose to differentiate 5 type-series in less than 15 km, and the limitations of lithostratigraphic nomenclature. In fact, only the type-serie V has some analogy with the classical Neuquén succession.

In the process we will proceed systematically, starting from the studied area, which benefits from detailed microfacies analysis, and then extending progressively the discussion to adjacent areas. Information on these areas is not only from bibliography, but also from personal observations, especially with regard to sedimentological features.

Figure 1 depictes the main morphostructural units of the western part of the Cordillera and the areas covered by the various paleogeographic maps included in this paper. Limits of the geographic regions of Argentine, Chile and Peru are also drawn. It is worth mentioning that the main areas of the Principal Cordillera are usually named after a city or after one of their drainage systems.

Concerning the paleogeographic maps, they are in stratigraphic order despite the fact that reasoning and extrapolation from the study area lead often to mention them in a different order insofar as generalization proceeds from the well-known to the least-known. As for the various scales used in the maps, they reflect the different degrees of knowledge and generalization for the specified stages.

Permanence and continuity of the andean volcanic arc

Indirect evidence: the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza

In this region (31°30'-33°S), it is possible to separate (Fig. 4), eastern successions (Espinacito, Los Erizos, and Los Sapos types) that indicate the basin´s eastern border, from a western belt of outcrops (Alma Negra type) with deeper facies characterised by early transgression and late regression. This belt of deeper facies is tentatively considered as representative of the basin axis, in spite of uncertainties on the amplitude of overthrusting involved in the Major Andean Overthrust (Vicente 1993 and 1998) and on the overprinted proportion of the basin. Alvarez (1997) recorded also longitudinal facies changes for the Los Patillos Formation.

Figures 3a, b and 4 summarise the principal results on this area and the resulting paleogeographic problems. Besides the clear narrowing of the basin towards the north, the defined facies belts establish clearly the eastern border, but does not indicate the western margin. This leaves the important question of the relationships with the remote Jurassic volcanics of the Chilean coast (Thomas 1958, Vicente 1976) (Fig. 2).

However, some indirect evidence of the existence of an active volcanic arc immediately to the west of the area indicates the western border of the basin. Thus, the thick Kimmeridgian continental conglomerates (Río Damas Formation), which overlie the western marine series (Río de los Teatinos, Arroyo Cencerro, Arroyo de los Gemelos, etc.), attest to the erosion of a very important andesitic volcanic arc and topographic high located more to the west. Furthermore, this arc was located on a pre-Andean basement, as indicated by some typical late Late Paleozoic pink hololeucocratic granite clasts collected in the detritus (Mpodozis et al. 1976).

Direct evidences

On the contrary, direct evidences of an active Jurassic volcanic arc are present in the neighbourhood of Los Pingos (31ºS) and Nacientes del Teno (35ºS) i.e. on both sides of our study area (Fig. 2).

Nacientes del Teno area: At the latitude of the Cordillera de Curicó (35°S) there are two major facies belts (Davidson 1971, Davidson and Vicente 1973, Davidson 1988).

The eastern facies are developed on the Argentinean slope, where the Río Atuel area is the most representative (Groeber et al. 1952, Volkheimer 1970, Riccardi et al. 1988 and 1991). The classical succession has a lithology similar to our Alma Negra type. It shows a Late Triassic - Early Jurassic transgression, a lower detritic sequence (Cuyo Group = Lower-Middle Jurassic) and an upper carbonatic sequence (La Manga Formation = Oxfordian). The detritic material, mostly coarse at the base (conglomerates) and fining to the top (fine sandstones, siltstones and pelites), has its exclusive source in the erosion of the eastern foreland basement (Permo-Triassic volcanics and Devonian graywackes) (Volkheimer 1970).

The western facies are represented on the Chilean slope of the international boundary, where they crop out due to a basement high in the headwaters (Nacientes) of the Río Teno. The Nacientes del Teno Formation (Klohn 1960) is very different from the previous succession (Fig. 5). It is characterised below by an Aalenian late transgression (Davidson and Vicente 1973), and by facies which, in the Bajocian, consist of a volcanoclastic set of breccias, andesitic graywackes and greenish tuffaceous microconglomerates with pyroclastic turbidites, slumps and olithostrome levels with 50 cm large exotic blocks of andesites (Davidson 1971, his photograph 5). The volcanoclastic material of this western facies, as well as its granulometric gradient, decrease eastwards, indicating an important western volcanic activity. Direction of slumps also shows steep slope to the east, i. e., toward the basin axis (Davidson 1988). All this, together with late transgression, indicates that the Nacientes del Teno facies belong to the relatively unstable basinal western margin, and represent the transition to an emergent area - abundant plant remains - with active volcanism.

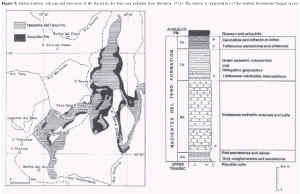

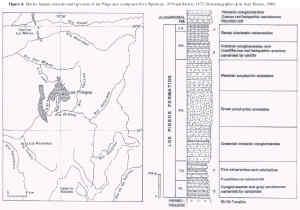

Figure 5: Marine Jurassic outcrops and type-serie of the Nacientes del Teno area (adapted from Davidson, 1971). The section is representative of the western Nacimiento-Vergara sector.

Los Pingos area: To the north (Fig. 2), at the latitude of Cordillera de Ovalle (31°S), the basin´s western margin was well defined during the Aalenian (Mpodozis et al. 1973, Mpodozis 1974, Rivano 1975 and 1980). At that time, the rather narrow basin (12-15 km) was almost completely filled by flows of porphyritic andesites, partly submarine (pillow lavas) and by a coarse volcaniclastic set of breccias, conglomerates and flows coming from the Northwest (Rivano 1975, Rivano and Mpodozis 1976) (Fig. 6). These deposits are clear different from those coming from the east, which consist, exclusively, of pre-Andean granitoids and rhyolites.

Figure 6: Marine Jurassic outcrops and type-serie of the Pingo area (composed from Mpodozis, 1974 and Rivano, 1975; lithostratigraphic units from Rivano, 1980).

Trace of the Jurassic Andesitic Volcanic Arc

The fact that on both sides of our study area the western margin of the Andean basin shows thick andesitic volcaniclastics coming from the west supports the existence of a Jurassic andesitic volcanic arc as western fringe of the Andean basin. The problem is to know the extent of such arc along the Central Andes (18°S - 43°S).

North

The first markers as indirect evidences occur at the latitude of Cordillera de Vallenar, where Hillebrandt (1973) and Hillebrandt and Westermann (1985) described Bajocian porphyrites, andesitic breccias and tuffs in the western succession (Quebrada La Totora or Chanchoquín, 28°45´S). Along the Río del Carmen, Nasi et al. (1990) described in Quebrada El Verraco (29°05'S) and Quebrada Guachacán (29°22'S) an andesitic volcanic sequence (Verraco Strata) intercalated by some fossiliferous limestones which yielded an Ammonoidea indet., what suggests a Liassic volcanic activity in the region. At the latitude of Precordillera of Copiapó, Toarcian-Bajocian andesitic conglomerates in the Quebrada Amolanas (28°S) (Jensen and Vicente 1976), as well as volcanic sandstones and sandy calcarenites with abundant volcanics in the Callovian of Quebrada Paipotito (27°S) (Cisterna and Vicente 1976), have been recorded. Immediately to the west are Bajocian flows of porphyric andesitic breccias in the sedimentary volcanics of Sierra de Fraga (Davidson et al. 1976).

It is in the coastal area of the "Norte Grande" where the most representative exposures are present. Conforming with the oblique alignment of the Jurassic paleogeography with respect to the present day morphostructural units, most of the Coastal Cordillera north of Taltal (25°24´S) is formed by a thick andesitic succession, attesting to the activity of this arc. This is the famous La Negra Formation (García 1967), very well developed in the Antofagasta region (23°45´S), where it is more than 10.000 m thick with alternating flows of andesites, mafic andesites, alkaline basalts and interbedded volcanic breccias, agglomerates and volcanic arenites. This impressive Lower-Late Jurassic formation shows intermediate volcanism, evolving from tholeiitic to calcalkaline and alkaline and attesting to an active subduction zone (Marinovic et al. 1995). This arc gives full support to the name La Negra Arc (Cisternas and Vicente 1976, Jensen et al. 1976). Furthermore, considering that at the latitude of Taltal the arc´s borders are well established: immediatly SW of Taltal, in Playa Los Bronces (70°32'W), the main volcanic sequence lies on volcanoclastic sediments which yielded Arnioceras sp. and Coroniceras sp. of Lower Sinemurian age (Covacevich 1985), while the eastern border is at the meridian of Sierra Candeleros (69º27´W), where Naranjo and Covacevich (1979) described flows of porphyric andesites with pillow structures in the Bajocian-Callovian, we conclude that the arc width is close to 100 km.

South

Important pyroclastic material, characterising the Early- Middle Jurassic, exists in the Chacay Melehue area (70°35´W, 37°15´S), south of Cordillera del Viento (Zollner and Amos 1973, Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980, Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995, Suárez and De La Cruz 1997). It consists of true pyroclastic turbidites with numerous slumps and levels with andesitic olistoliths (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980). A few measurements of slump folds indicate a slope to the south-east. In the Aalenian there are channelized bodies of massive sandstone and microconglomerates, besides dish structures and the orientation of the oblique bedding indicates a paleocurrent direction towards the south-east. All this, and the proximal facies confirm the proximity to the west of the active volcanic arc. Furthermore, immediately to the west (Arroyo Michicó and Chacay Melehue area) porphyritic volcanic flows are interbedded in the Lower Jurassic succession (Zollner and Amos 1973, Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995).

At the latitude of Río Agrio, near Loncopué (70°35´W, 38°S), there are important pyroclastic flows within the Callovian, including fluxoturbidites and olistostrome levels with imbrication of clasts indicating a western or northwestern origin (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980).

Chotin (1975) reported andesitic breccia flows with pillow structures, interbedded in Middle Jurassic strata, at the 39º S latitude, immediately to the east of Lago Aluminé, in the Cerro Mallin de los Caballos section (71°45´S), and further north in Lonquimay (38°30´S), levels of andesitic conglomerates and tuffs, attesting to proximate contemporaneous volcanic activity to the west. Suárez et al. (1988) reported for the Icalma region (38°48´S), the existence of a submarine volcanicsedimentary complex with pillow flows and pyroclastic breccias alternating with Pliensbachian-Toarcian fine bedded shales. Next is the Aluminé Formation (39°15´S), a typically volcanic-sedimentary set of rhyolites, andesites and dacitic tuffs with Early Jurassic fossiliferous marine intercalations (Cuerda et al. 1981). To the south, the formation is correlated with the Piltriquitrón Formation cropping out with similar features in the Bolsón region (42°S) of the northern Patagonian Cordillera (Lizuaín 1980 and 1999).

It is also important to stress the surprisingly close lithologic similarities between the Futaleufú Group, described by Thiele et al. (1979) at the 49ºS latitude of the Patagonian Cordillera, and the La Negra Formation of Northern Chile. The former is a 2000 m thick volcanic-sedimentary set, mainly of andesitic and dacitic flows, breccias and tuffs, with an important fossiliferous marine intercalation (Tres Monjas Formation), 250-300 m thick of Middle Jurassic shales, tuffs, volcanic arenites and a calcareous level with Ostrea. Furthermore, to the west, this level becomes volcanic, in some cases with pillow structures.

On that basis, there are evident similarities of this group with the andesitic volcanics of the Montes de Oca Formation described by González Díaz (1979) more to the north in the Lago Nahuel Huapi region (40°30´- 41ºS), previously described as Huemul Group by González Bonorino (1974, 1979) and the Cerro El Fuerte Formation of Greco (1975) in the Cerro Tronador geological map. These last two units, despite the fact that they are strongly metamorphosized by Upper Cretaceous and Miocene intrusives (González Díaz and Valvano 1979, Diez and Zubia 1981, González Díaz 1982), have usually two members, a lower one mainly volcanic with dacitic and andesitic flows, and an upper one mainly volcanosedimentary with black shales, volcanic arenites, conglomerates and tuffs, i.e. a succession quite similar to the Futaleufú Group.

Finally, immediately to the south at the latitude of lakes La Plata and Fontana (44°30´S), Ramos (1976) described the Lago La Plata Formation resting, to the east, on marine Early Jurassic (Malumián and Ploszkiewicz 1976) and overlain by the marine Tithonian of Arroyo Pedregoso (Tres Lagunas Formation) (Ramos and Blasco 1978). It is possible to conclude that this north Patagonian Jurassic volcanism represents the Middle and, in part, the Upper Jurassic, resulting in Haller´s et al. (1981) reference to a Middle to Upper Jurassic Volcanic Association.

These few examples indicate the extension and continuity to the south, at least up to 43°S latitude (Diez and Zubia 1981), of the andesitic volcanic arc bounding the Andean basin to the west. It should be mentioned that beginning at latitude 40°S there are dacitic components, which would indicate an axial evolution of this volcanism to more acidic types (Haller and Lapido 1980).

This volcanism largely surpasses the Cordillera region and characterizes large areas of extra-Andean Chubut from Sierras of Tecka and Tepuel (Haller et al. 1981) to Pampa de Agnia (Nullo 1983). In the last area, two major volcanic sets are usually recognized: a Lower Jurassic inferior one (Puntudo Alto and El Cordoba Formations) and a Middle Jurassic upper one (Lonco Trapial Formation), separated by Upper Lower Jurassic marine deposits (Osta Arena Formation). Especially worth mentioning are, in the eastern region, the numerous marine intercalations of volcanic arenites with bivalves in the upper part of El Cordoba Formation (Nullo 1983). They represent important lateral facies changes, attesting to the gradual drowning of an active andesitic arc with a relatively complex archipelago paleogeography. This explains the multiplicity of the local stratigraphic nomenclature.

These studies indicate a Patagonian Jurassic arc about 200 km wide, representing the prolongation to the south of the Andean arc and corroborates the obliquity of the Jurassic paleogeography with respect to the present day geography.

Volcanic zonation and the double-arc

Our study area and its paleogeographic organization during the Jurassic (33°S), show the importance of comparing the andesitic volcanism of the western basin border at this latitude with the rhyodacitic volcanism of the Chilean coast (Vicente 1976). Although contemporaneous, they are spatially separated. Thus we have proposed a long time ago (Vicente 1976) to distinguish two belts within the Middle Jurassic Andean Arc (Fig. 7):

1) A Western belt, characterized by a dominantly acid volcanism with keratophyres, defining a "rhyodacitic volcanic arc" of calc-alkaline type with tholeiitic tendency;

2) An Eastern belt, characterized by a mainly andesitic, typically intermediate volcanism, defining an "andesitic volcanic arc" of calc-alkaline type with alkaline tendency.

This differentiation of the magmatic backbone in a double arc, agrees with the classical observation of increasing alkalines towards the foreland, characterizing the insular arcs (Kuno 1959, Sugimura 1968, Hatherton and Dickinson 1969). This zonation of the volcanic arc completes the structural scheme of the Andean margin for the Lower and Middle Jurassic. We now appreciate the importance of the intermediate magmatic backbone separating the western successions, with features of subsiding and volcanized platform, transitional to the sedimentary succession of the open-Pacific domain (El Melón sector), as a forearc basin. It should be stressed that the structural scheme shown by the Aconcagua transect (32°40´S) is the most completely known. Due to the slight obliquity of the Jurassic paleogeography relative to the present day topography, the northern components of the western rhyodacites extend offshore, so that the andesitic arc remains only in the coastal chain, whilst southwards the Pliocene-Quaternary deposits of the Chilean longitudinal valley and the Cordilleran Upper Cenozoic volcanics cover most of its supposed extension. Nevertheless, the presence of acidic facies in the North Patagonian Cordillera south of 40°S may be interpreted as the continuation of the rhyodacitic western arc, whilst the andesitic arc mainly characterizes the Chubut Precordillera.

Figure 7: Diagrammatic paleogeographic section through the Andean continental-margin arc-trench system during Bajocian (from Vicente, 1974 and adapted to Dickinson and Seely's, 1979 terminology). 1: Pre-Bajocian cover and pre-Andean basement (continental crust); 2: Keratophyres and quartz-keratophyres lava flows; 3: Andesitic volcanism; 4: Volcarenites and lithic tuffs; 5: Lutites; 6: Calcarenites; 7: Red beds; TSB: Trench-slope basins.

General implications

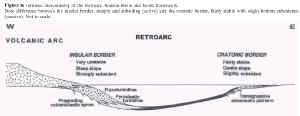

The Andean basin shows strong asymmetry between the western (insular) margin, unstable and with steep slope (slumps, olisthostromes, pyroclastic turbidites), and the eastern (cratonic) margin, relatively stable and with a weak slope (Fig. 8).

Existence of an active apparently continuous volcanic arc that acted as a barrier to the Pacific Ocean contradicts the requirement for oceanic connections of the Andean basin. We will therefore analyze global basin evolution along the Central Andes in order to spot the potential seaways through the arc.

Figure 8: Intrinsic dissymmetry of the Retroarc Andean Basin and facies framework. Note difference between the insular border, steeply and subsiding (active) and the cratonic border, fairly stable with slight bottom subsidence (passive). Not to scale.

Evolution of the andean basin during the lower jurassic: the transgressive process

Latitude of study area (31°30´ - 33°S)

In the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza the transgression starts very likely in the Early Pliensbachian (Fig. 4). The Alto Mondaca and Arroyo Ventisquero Mesa sections, belonging to the outcrops of the westernmost belt (Alma Negra type), yielded Arieticeras sp. (Margaritatus Zone). As the fossiliferous level is 80 m above the section base, the transgression may have begun in the earliest Pliensbachian. In the Río de Los Patos type section Volkeimer et al. (1977) mentioned Protogrammoceras ex gr. normanianum 48 m above the base documenting there again the Upper Pliensbachian. Therefore, Sinemurian levels appear to be missing at this latitude.

North

High Cordillera of Ovalle and Elqui region (31° - 29°30´S): The transgression is dated here as Pliensbachian and perhaps Late Sinemurian as attested by the following reference points:

- Los Pingos (30º54´S, 70º32´W), southeast of Ovalle. Mpodozis (1974) and Rivano (1975) recorded a poorly preserved ammonite which Hillebrandt (2002) dated as Late Sinemurian.

- Río Mostazal (30º45´S, 70º34´W), southeast of Ovalle. Mpodozis (1974; cf. Mpodozis and Cornejo, 1988) recorded Trigonia (Frenguelliela) tapiai Lambert, a species dated as mainly Pliensbachian by Pérez and Reyes (1977). According to Hillebrandt (2002) the transgression is dated in the whole area as Late Sinemurian.

- Quebradas Matahuaico and Tres Cruces (30°05´S, 70°36´W), east of Vicuña. Hillebrandt (2002) recorded Late Sinemurian-Pliensbachian ammonites.

- Portezuelo de la Punilla (29°41´S, 70°12´W) and Los Cuartitos (29°38´S, 70°11´W). The transgression in the whole area is dated as Late Sinemurian by Hillebrandt (2002).

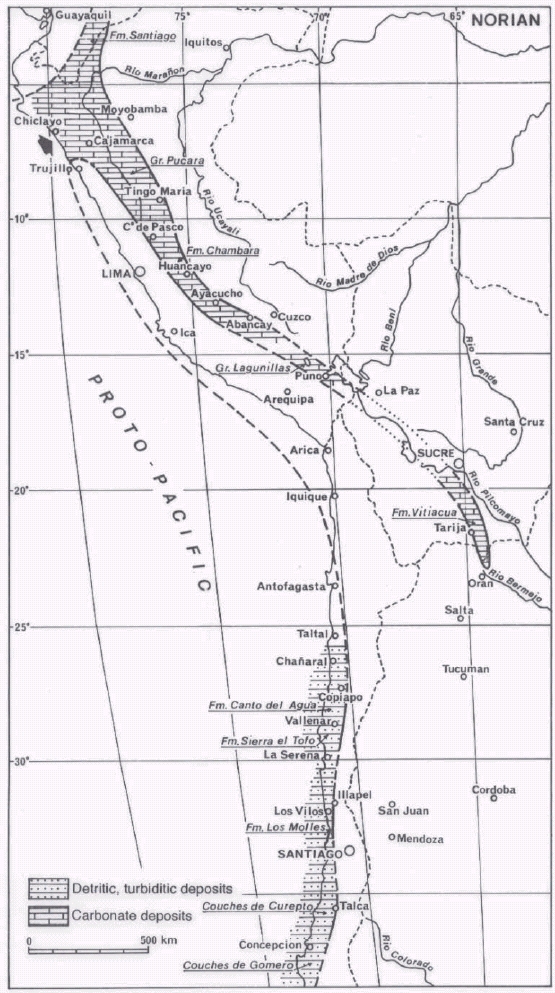

Figure 9: Distribution and paleogeography of marine Upper Triassic (Norian) deposits on the western margin of Gondwana between latitudes 3° and 37°S. Note the difference between terrigenous deposits of the Chilean Margin and carbonate deposits of the precursor Peruvian Trough fed by the Olmos Gulf. The proposed connection between Puno and the Bolivian subandean zone is based on the discovery of Monotis aff. subcircularis in the Vitiacua Formation (YPFB-GEOBOL, 1978). At Abancay the base of Pucara Group is not exposed (Marocco, 1975) but all evidence suggests that the Upper Triassic must be represented, just as in Puno where the lowermost Sinemurian levels of Lagunillas Group are inquestionably deep (Vicente, 1981).

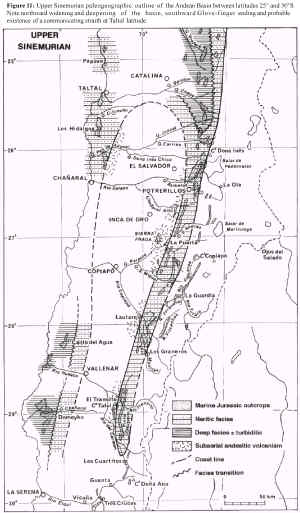

High Cordillera of Vallenar area (29º18´- 28º45´S): In the Río Transito region of the High Cordillera of Vallenar, the transgression is clearly Late Sinemurian (Hillebrandt 1971, 1972, 1973 and 2002)) (Raricostatum Zone) along the central belt of outcrops (70°18´W) from Quebrada La Papa to Quebrada Pinto (Fig. 11). Furthermore, the westernmost (Cerro Tatul, Quebrada Las Pircas, Vega Redonda and La Plata) and easternmost (Río Plata, Cerro Picudo) belts have Pliensbachian transgressions (Hillebrandt 1973). Thus, the belt characterised by a Late Sinemurian transgression is at most 15 km wide at this latitude (Jensen et al. 1976), which, taking into account the tectonic shortening of 40% assessed by Reutter (1974), indicates that the narrow "neo-Sinemurian channel" had at most a width of 25 km but narrowed rapidly to the south (Fig. 10). Although Sinemurian it is still present at 30º - 31ºS (Quebrada Matahuaico and Mina Los Pingos) (Hillebrandt 2002).

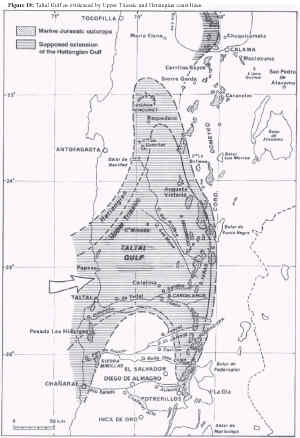

Figure 10: Taltal Gulf as evidenced by Upper Triassic and Hettangian coast lines.

Figure 11: Upper Sinemurian paleogeographic outline of the Andean Basin between latitudes 25° and 30°S. Note northward widening and deepening of the basin, southward Glove-finger ending and probable existence of a communicating straith at Taltal latitude.

Southern area of the Copiapó Precordillera (28°20´ - 27°50´S): This region still shows a Late Sinemurian transgression. Basically the Raricostatum Zone is represented by Paltechioceras cf. oosteri (Dumortier) (Hillebrandt 2002) in Hacienda Manflas, but Hillebrandt (1970) also indicated the presence of some fragments of Oxynoticeras sp. as representing the Oxynotum Zone. As these levels are about 100 m above the base of the succession (Jensen 1976), it is possible to assume that the lower sandstones and calcarenites without ammonites could be Lower Sinemurian (Jensen and Vicente 1976). More to the South, in the head of Río Manflas the Salto del Toro profile (28°20'S) yielded an Epideroceras of Late Sinemurian (Hillebrandt and Schmidt-Effing 1981).

Northern area of the Copiapó Precordillera (27°30´ - 26°20´S): The Sinemurian is represented here by an assemblage with Arnioceras cf. A. rejectum Fucini. and Asteroceras cf. C. confusum Spath (Sowerby), characterising the Obtusum Zone, found by Hillebrandt (1973 and 2002) in the Yerbas Buenas section (27°18´S - 69°37´W), south of Cerro La Ternera. Also present is the Raricostatum Zone, with Orthechioceras angustiumbilicatum Hillebrandt and O. cf. O. incaguasiense Hillebrandt (Hillebrandt 1973 and 2002). At this latitude the presence of Upper Sinemurian becomes permanent: thus the Oxynotum and Raricostatum Zones have been recorded in Vega Redonda (27°09´S, 69°39´ W) east of La Puerta (Cisternas and Vicente 1976), the Raricostatum Zone with Orthechioceras cf. O. incaguasiense Hillebrandt in Quebrada Paipote (Hillebrandt 2002) and in the middle part of Quebrada Asientos (Montandon area, 26°23´S, 69°25´W) at the Chañaral latitude (Pérez 1978 and 1982).

It is now possible to define the two margins of the late Sinemurian marine channel (Jensen et al. 1976). Three sections are specially important in this respect (Fig. 11):

- The Juntas del Río Copiapó area (28°S), where the western belts of Tranque Lautaro and Manflas with a Late Sinemurian transgression differ from the eastern belt of Iglesia Colorada with a Pliensbachian transgression (Jensen 1976; Jensen and Vicente 1976).

- The San Andrés-Quebrada Paipote area (27°S), where, compared with the San Andres-Vega Redonda-Quebrada Yerbas Buenas belt, the La Guardia-Río Figueroa-Vega La Junta eastern belt has a Pliensbachian transgression (Hillebrandt 1973; Jensen 1976; Davidson et al. 1978), as in the La Puerta- Quebrada Paipotito western belt (Cisternas and Vicente 1976), whilst farther west, Sierra de Fraga was reached by this transgression only in the upper part of the Lower Bajocian (Davidson et al. 1976, Sepúlveda and Naranjo, 1982, Hillebrandt 2000).

- The Quebrada Asiento area (26°23´S), where the Sinemurian Montandon belt (Pérez 1978) opposes the eastern Pedernales belt (Hillebrandt 1970) and the western Río La Sal (Hillebrandt 1973) – Chañaral Alto (Oviedo 1977) belt with a Pliensbachian transgression.

In summary, the Late Sinemurian belt of the Copiapó Precordillera was at most 20 km wide (Jensen et al. 1976) and even was less than 10 km in width at the Quebrada Asientos latitude, due to tectonic causes (García 1967). Thus, estimating a tectonic shortening in the order of 25% (Jensen 1976) the basin would have had an original width of about 25 km.

Cordillera Domeyko area (25°36´ - 24°30´S): Surveys carried out in Cordillera Domeyko show that at the Quebrada Incaguasi latitude (25°36´S, 69°15´W) (Hillebrandt 1970 and 2002), the transgression can be dated as Late Sinemurian (Raricostatum Zone) on the basis of Plesechioceras domeykoense and Orthechioceras incaguasiensis Hillebrandt spp. However, the presence of some Phylloceras sp. and Lytoceras sp. would indicate deeper depositional environments (Fig. 11) than those found in the Copiapó Precordillera, where "leiostracans" are absent, whilst bivalves, gastropods and brachiopods dominate.

This suggests that the transgression began there earlier. Thus, 30 km to the north, on the western flank of Sierra de Vaquillas Altas (25°20´S, 69°14´W), the Hettangian is represented (Naranjo and Covacevich 1979, Chong and Hillebrandt 1985, Hillebrandt 1990 and 2000a) by the presence of Psiloceratinae and Schlotheimiinae and the Lower Sinemurian by Arietitidae. Furthermore, 25 km to the north at 25°07´S latitude begins the Sierra de Varas region, the classic area of the Hettangian since the studies of Chong (1973, 1976 and 1977), Hillebrandt (1973 and 2000), Quinzio (1987) and Ardill et al. (1998). Localities such as Quebrada Punta del Viento (25°07'S, 69°15'W), Quebrada Las Mulas (25°07´S, 69°10´W), Aguada Vizcachas (25°02´S, 69°13´W) ), Quebrada Bonita (24°59'S, 69°12W), Aguada El Minero (24°53'S, 69°12'W)) and Aguada de Varas (24°49´S, 69°10´W) yielded ammonites of the Bayoensis, Reissi and Canadensis Andean Zones, representing according to Hillebrandt (2002), the Liasicus Zone and part of Angulata Zone.

At this latitude, the width of paleontologically dated Hettangian outcrops is more than 30 km, without considering tectonic shortening that in this part of the Precordillera is estimated to be 50% (Chong 1973 and 1976).

Thus, three major facies belts are recognised (Fig. 10): a western shaly one, centred in Sierra Argomedo (69°20´W); a central sandy one, at the western slope of Sierra de Varas (69°10´W); and an eastern one, at the eastern foot of Cordillera Domeyko (69°06´W) where conglomerates and sandstones in association with coral facies are dominant (Chong 1973; Hillebrandt 1973). This arrangement indicates a wesward increase in depth, whilst the coral facies marks the eastern basin margin.

The studies of Chong and Hillebrandt (1985), Gröschke and Hillebrandt (1985) and Hillebrandt (1990 and 2000) show clearly that in this area the transgression began in fact in the Late Triassic. They pointed to an outstanding series of Upper Triassic fossiliferous outcrops along the Cordillera Domeyko between 26° and 23°30´S, i. e., for a distance of about 300 km with a width of about 20 km at the latitude of Sierra Argomedo (24°45´S). The marine Triassic is mostly in carbonated facies, highly littoral, with abundant corals (Thecosmilia sp.), brachiopods (Zugmayerella sp., Clavigera sp. and "Spiriferina" sp., bivalves (Minetrigonia pascoensis (Steinmann), Myophorigonia paucicostata (Jaworski), Perugonia lissoni (Steinmann), Cassianella sp., Septocardia peruviana (Cox), Palaeocardita peruviana (Cox), Schfhaeutlia americana (Cox), Liostraea sp., Gryphaea sp.) and gastropods (Chartronella spp.). Deeper, finely laminated sandy facies, follow above transitionally to the Hettangian. Within this succession, Norian and Rhaetian levels were recognised by the presence, respectively, of Arcestes and Choristoceras. On the contrary, to the north-west, from Sierra Minillas in the south to Cerros de Cuevitas in the north, the marine Hettangian rests on continental Triassic.

Baquedano area (23°40´ - 23°S): The last known Hettangian belt lies 130 km to the NW, in the Baquedano area. The outcrops of Cerros de Cuevitas (28º38´S) south of Baquedano (Ferraris and Di Biase 1978, Di Biase 1985, Hillebrandt 2000a), with Psiloceras sp., Kammerkarites cf. diploptychoides Guex Discamphiceras cf. reissi and Laqueoceras sp. at the base, as well as those of Sierra de Rencoret (23º 20´ S) to the north (Tobar 1966, Hillebrandt 2000) with Psiloceras cf. minillaensis Hillebrandt, are clearly uppermost Lower to Middle Hettangian. These outcrops lie farther westly than those of Sierra de Varas. This location, together with the Late Sinemurian early transgression, 60 km to the east, in the Cerritos Bayos area (69º10´W) (Baeza 1976 and 1979, Hillebrandt 2002), implies a remarkable northwestern deflexion of the Hettangian coast and a retreat to the west of nearly 75 km (Fig. 10). However, is worth mentioning the presence of Hettangian with Psiloceras sp. in the Cerros de San Lorenzo (22°26'S, 69°02'W) west of Calama (Elger 1998, Hillebrandt 2002) and some outcrops along the western slope of Sierra Moreno as Quebrada Chug Chug (22°06'S, 69°07'W) and Quebrada Sama (21°23'S, 69°59'W) with Hettangian ammonites (Hillebrandt 2000), whilst west of Quillagua there are levels with Late Hettangian-Early Sinemurian ammonites (Maksaev and Marinovic 1981). These recent discoveries so corroborate the previous record by Niemeyer et al. (1985) of Psiloceras sp. at the base of Quebradas Cuchita-Cortaderas section (21°21´S), in the central-west area of their Cerro Yocas Geological map. That suggests the northward continuation of a narrow Hettangian furrow at least up to this latitude (Fig. 10).

Northernmost Chile and southern Peru (20°23 - 15°50'S): Further to the north, the few known outcrops indicate a transgression in the Sinemurian. Where the following fossils were recorded: Arietites sp. in the Longacho Formation (20°23´S, 69°21´W) north of Pica (Galli 1957, Galli and Dingman 1962) and Arietites and Arnioceras at the base of a correlative formation in Quebrada Aroma (19°32´S, 69°18´W) near Chismiza (García 1967).

Finally, in southern Peru, Arnioceras and Asteroceras are present at the base of the Pelado Formation in the Palca area (17°48´S, 69°54´W) northeast of Tacna (Wilson and García 1962, Salinas 1986), and Arnioceras sp., Vermiceras sp., Metophioceras ? sp. and Crucilobiceras ? sp. occur in the calcareous lower unit of the Lagunillas Group cropping out west of Puno (Portugal 1974, Vicente 1981). These deposits even have been recognized as far as Curahuasi (13°36'S, 72°38'W) at the NE of Abancay, and have yielded some Asteroceras sp. of the Upper Sinemurian (Ligarda et al. 1991).

Taltal Hettangian Gulf: Thus, it is evident that a Hettangian strait or an entrance gulf should be placed between 23° and 26°10´S latitude (Fig. 10). In this connection, the existence of marine Hettangian in the Coastal Cordillera, precisely between Paposo (25°01´S) and Chañaral (26°15´S) (Cecioni 1960, Ortiz et al. 1960, Zeil 1960, García 1967, Mercado 1980, Naranjo and Puig, 1984) is significant, i. e. the classic Pan de Azúcar Formation (Ortiz et al. 1960, Naranjo 1978a), well exposed in Sierra Minillas (26°10´S), Quebrada Pan de Azúcar, Quebrada Cachina, Posada de los Hidalgos and Quebrada Cifuncho (23°35´S), which rests unconformably on continental Triassic and Paleozoic basement. This formation has yielded an abundant fauna (Covacevich in Naranjo 1978b) of the Lower to Middle Hettangian (Primocostatum to Reissi Zones = Planorbis to Liasicus Zones) and of Schlotheimiidae (Zeil 1960, Covacevich in Naranjo 1978b, Hillebrandt 2000) of the Middle to Upper Hettangian (Peruvianus to lower Canadensis Zones = upper Liasicus to Angulata Zone). In the equivalent Paposo Beds (Arabaz 1971, Ferraris 1978, Quinzio 1987) of northern Taltal, Chong (1973) has demonstrated the important lithologic analogies with the so called "western" facies of Sierra Argomedo.

South of Sierra de Minilla, at about 26°09´S latitude, within the Pan de Azucar Formation, there are strong facies changes to the east, so that at the crossing point of the Pan-American Highway and the road to Pan de Azúcar are developed littoral facies with the dominance of bivalves and corals. These deposits pass gradually to the east into red sandstones and 3 km further, the volcanics of La Negra Formation rest directly on the Paleozoic (Naranjo 1978a, his Profile B-B´). The succession exhibits a remarkable increase in thickness to the north between Quebrada Pan de Azúcar and the Posada Los Hidalgos area, i. e. over 40 km from < 200 m to a > 800 m shaly facies (Naranjo 1978b).

Therefore, all evidence locates the entrance of the "Hettangian gulf" at the latitude of Taltal (25°20´S), i. e., precisely opposite to the Vaquillas Altas and Sierra de Varas regions (Fig. 10).

From our point of view, this is the first area where the paleo- Pacific waters penetrated on the continental margin before they advanced longitudinally to the north and south to form the retroarc basin. We propose to name this forerunner gulf as "Taltal Hettangian Gulf". However, note that this interpretation varie drastically from the one claimed by Hillebrandt (2000) according to which "during the Hettangian the Jurassic sea transgressed from the present-day Precordillera in the East to the present-day Coastal Cordillera in the West" without care of the origin of sea waters.

This Hettangian gulf is actually an extension of the initial neo-Triassic gulf (Fig. 10), indicated by the marine Triassic outcrops of Cordillera Domeyko (Chong and Hillebrandt 1985, Mpodozis and Cornejo 1997)) and Central Depression (Marinovic and Covacevich 1994, Marinovic et al. 1995). Yet lacking known Triassic marine deposits on the coastal area (Naranjo and Puig 1985, Suárez and Bell 1992), makes less evident the placement of an eventual marine strait. The mainly anastomosing fluvial character of the thick Cifuncho Formation south of Taltal, underlying the marine Hettangian, the unimodal paleocurrent direction pointing to the SE (Suárez and Bell 1994) and the presence of finer and more sedimentary facies to the north (Suárez et al. 1982), indicates that the gulf entrance was located farther north. Now, north of Paposo, the basal part of the Cerro Yumbes section (Quinzio 1987) is incomplete, although Marinovic et al. (1995) and Hillebrandt (2000) recorded Hettangian ammonites, placing this area as a potential candidate. Hettangian deep facies with ammonites and radiolarians rest on probably submarine synsedimentary volcanics, which in no way represent the succession transgressive basal part. Therefore, it would be possible to find marine Triassic in this area. Nevertheless, it should be realised that this reconstruction depends the exact value of the sinistral longitudinal displacement of the coastal block with respect to the Cordillera, related to activity of the Atacama fault zone during the Early Cretaceous (Scheuber et al. 1995). Moreover, Forsythe et al. (1987) recorded paleomagnetic data which suggested a 30° clockwise rotation for the coastal block. In that case the paleocurrents may have flowed in fact from the West (Suárez and Bell 1994).

The localization of a strait about latitude of Taltal is imposed by the distribution of Hettangian outcrops and the transgressive pattern just showed. It is in agreement with the suggested alternate paleogeographic interpretation of Suárez and Bell (1992, their fig. 2) which separates, in Late Triassic time between latitudes 24°S and 29°S, a northern marine basin (Profeta Basin) from a southern one (San Félix Basin) by a NNW-trending continental ridge with volcanic activity and intra-arc rifted continental basins (Cifuncho and La Ternera). This ridge gives evidence for an incipient volcanic arc from that time linked to the beginning Pacific subduction. In that geodynamic setting, it is clear that the San Félix Basin belongs to the forearc while the Profeta Basin, as part of our Tarapacá Basin, represents the retroarc. That setting is well exampled about latitude of Vallenar (28°45'S) where the thick clastic San Félix Formation of Alto del Carmen in 69°30'W longitude records an alluvial fan and shallow marine fan-delta complex developed in a fault-controled extensional setting, adjacent eastwards to a volcanically and tectonically active continental arc (Bell and Suárez 1994). Though relatively narrow at this latitude, that arc unquestionably restained the Late Triassic transgression from the Pacific to the west since more to the east, in the Río Tránsito area (70°18'W), the transgression from north in the retroarc began only in the Late Sinemurian (Fig. 11). Otherwise, the pyroclastic breccias and tuffs interbedded in the lower member of the San Félix Formation record much the Ladino-Carnian Spilite-Keratophyre complex of Pichidangui Formation of Los Vilos region (32°S) in the Coast Range of the Norte Chico (Vicente 1976) which characterizes the Western Belt of the Arc. This tholeiitic bimodal suite expresses an extensional geotectonic setting of the belt (Morata et al. 2000). Moreover, the San Felix Formation grades westwards to the Canto del Agua Formation (Moscoso and Covacevich 1982, Moscoso et al. 1982), a turbiditic complex of the Coast Range which carries out the transition to the accretionary wedge of the time.

We cannot conclude, however, that this gulf was the only sea way to the Andean Basin. More to the north, at the latitude of Peru, the transgression advanced from north to south (Mégard 1973 and 1978). It began during the Norian in central Peru and at first formed a narrow channel, centred on the Central and Eastern Cordilleras, connecting to the north, at about 5º S, with the open sea and ending in a narrow bay in Tarija, Bolivia (Fig. 9). During the Early Jurassic, this basin was extended progressively towards the SW, so that, beginning in the Sinemurian, a connection seems to have existed with the Chilean Norte Grande Basin, via Puno and Palca (Vicente 1981).

South

Neuquén region (34°50' - 40°08'S): The age of the transgression to the south of the area here studied, i.e. at the latitude of the Aconcagua-Neuquén Basin between 33º and 40ºS remains to be analysed. While we have shown in the previous section that the main transgression advances from the Taltal Hettangian gulf towards the south (Jensen et al. 1976) [26º20´S latitude in the Late Hettangian, 27º30´S latitude at the end of the early Sinemurian, 31°S latitude at the end of the late Sinemurian and the study area (32ºS) in the middle Pliensbachian and to assess a transgressive speed of about 9 cm/year (= 730 km in 8 My)], this information is not useful to analyse the evolution at the latitude of Neuquén.

The age of the transgression in Neuquén has been the subject of untimely generalisations that were later revised. Thus, Groeber (1924) mentioned marine Triassic in Neuquén, based on the presence of "Myophoria neuquensis" Groeber, which subsequently was found in Chubut together with Lower Jurassic taxa (Levy 1966). Regarding the supposed existence of Upper Sinemurian (Behrendsen 1891, Burckhardt 1902, Jaworsky 1925, Groeber et al. 1952, Stipanicic 1969, Stipanicic and Rodrigo 1970) at the classic localities of Río Atuel, Sierra Chacai Co and Piedra Pintada, it was based in the record of "Oxynoticeras spp." and especially of "O." behrendseni Jaworski (1925) and "O." leptodiscus Behrendsen (1891). Subsequently, some of those ammonites, usually not figured, were assigned (Hillebrandt 1970, Riccardi, in Damborenea et al. 1975) to the Early Pliensbachian genus Radstockiceras Buckman. Finally, Hillebrandt (1981) has shown that many of them belong to Fanninoceras, a genus originally described from the Upper Pliensbachian of North America. Jaworski´s species, including "O. leptodiscus" was placed by Leanza and Blasco (1991) in Austromorphites Leanza and Blasco, i.e. A. behrendseni, and the species was dated as late Early Pliensbachian (Hillebrandt 1987).

To date presence of Hettangian, Sinemurian and lowermost Pliensbachian has only been proved in the Río Atuel area (34°50´S). Jaworski (1925) and Stipanicic and Bonetti (1970) recorded Early Sinemurian Arietitidae, and Hillebrandt (1973, 1981, 1987 and 1989) Late Sinemurian in material coming from the Puesto Araya Formation (Volkheimer 1970). In the same area, immediately to the west, Riccardi et al. (1988 and 1991) showed that the transgression is still younger. Thus the Arroyo Alumbre-Arroyo Malo section yielded the first Argentine Hettangian ammonite fauna in turbiditic facies, overlain by fossiliferous lower Sinemurian. Furthermore, the lower part of the same section yielded an Upper Triassic fauna, including Rhaetian ammonites (Riccardi et al. 1997; Riccardi and Iglesia 1999). Thus, at this latitude the marine transgression began in the Rhaetian-Hettangian and advanced eastwards on the fluviatile (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980) conglomerates of the El Freno Formation.

Farther south, Sinemurian has not been recorded and the oldest marine Jurassic, represented at different localities, yielded late Early to Late Pliensbachian ammonites (Riccardi 1983). Thus in Sierra de Chacai Co (39º16´S, 70º15´W), south of Zapala, the transgression would begin only in the late Early Pliensbachian (Hillebrandt 1973), dated by Austromorphites behrendseni (Jaw.) and some fragments of Polymorphitinae just above the basal conglomerate (Volkheimer 1973). Similarly in Piedra Pintada (40º08´S, 70º16´W), near the southern end of Neuquén, the Pliensbachian transgression is supported by the presence of Fanninoceras spp. at the base of the succession (Damborenea et al. 1975).

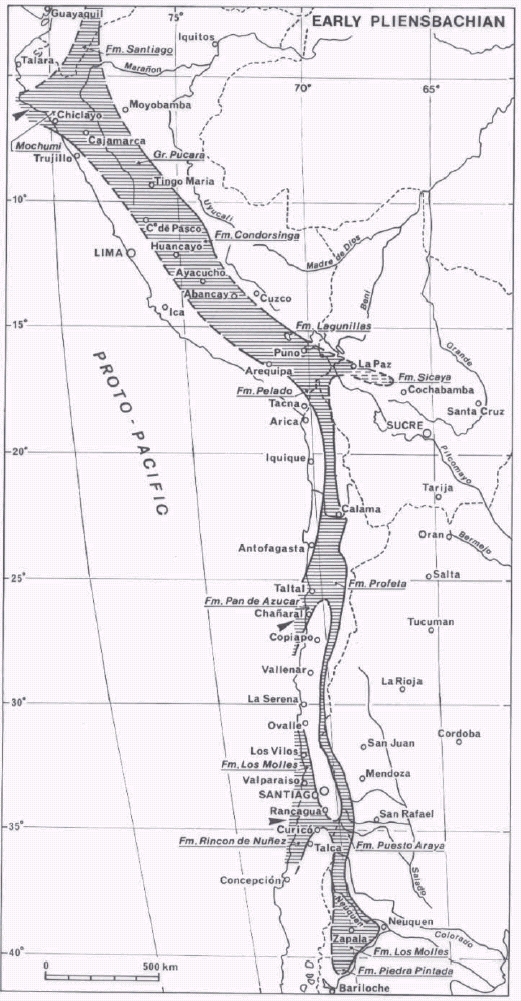

Figure 12: General Early Pliensbachian paleogeographic outline of the Andean Basin between latitudes 3° and 40°S. Note the striking continuity of the basin over more than 3500 km, its situation as marginal retroarc basin with a western insular border and the three communicating straits with the Proto-Pacific. Reconstruction doesnot include tectonic shortening. If considered at the latitude of Peru the width of the Basin should be twice as wide, and the coast line should be located more to the west.

Extra-Andean Chubut region (42°30' - 44°30'S): At this latitude, Piatnitzky (1936) and Feruglio (1949) recorded marine Jurassic on the basis of the supposed presence of Oxynoticeras sp., dated as Sinemurian, and of other ammonite material compared with Pliensbachian-Aalenian species, most of which were originally described from Neuquén and Mendoza, although in Chubut they were found in the same levels. A study of some of these localities, especially Cerro Negro, by Musacchio and Riccardi (1971), produced only Toarcian Dactylioceratidae (Bifrons to Variabilis Zones, cf. Hillebrandt 1987, p. 118) and Harpoceratidae, whilst Sinemurian, Pliensbachian and Aalenian ammonites were not recorded (Westermann and Riccardi 1972). The record of some Fanninoceras in Sierra de Lonco Trapial of the Pampa de Agnia area (Blasco et al. 1979, Nullo 1983) suggested that, as for Neuquén and Mendoza, this type of ammonites was previously misidentified as Oxynoticeras spp. and, therefore, the transgression began in the late Pliensbachian. The finds of some Fanninoceras spp. (det. Riccardi, during the Patagonian Field Trip of IGCP 322, October 1996) in association with the bipolar bivalve Kolymonectes (det. Damborenea and Manceñido) confirms this conclusion.

But these data refer to the eastermost Lower Jurassic belt, which appears to have a thinner succession than the western belt of Sierra de Tecka, Sierra Tepuel and Nueva Lubecka (Lesta and Ferello 1972), and the latter belt could have had an earlier transgression. The record of "Oxynoticeras" by Suero (1947) from the lower levels of Tepuel and Tecka, may have been of Fanninoceras, considering similar misidentifications in Neuquen, so that at least a Pliensbachian age of the transgression is possible. Existence of even older strata has been recorded by Massaferro (2001) in Cerro Cuche, west of Tecka. In contrast, at the latitude of Nueva Lubecka (44º31´S, 70º25´W) the record of Hildoceras and Harpoceras indicates Toarcian (Wahnish, 1942).

Malumián and Ploszkiewicz (1976) recorded from 40 km further west (village of Apeleg, near the locality of Loncopán; 44º40´S, 70º47´W) marine Toarcian, with Peronoceras aff. subarmatum (Y. & B.), P. vorticellum (Simpson) and Catacoeloceras sp. (Blasco et al. 1980). This is the westernmost known outcrop, and allows us to infer that at this time the basin was 120 km in width. However, to the east, 342 m of marine Lower Jurassic, transgressive on Permo-Triassic have been drilled in a borehole at the latitude of Laguna Palacios (44º47´S, 69º19´W) (Ferello and Lesta 1973). The sequence, considered (see Uliana and Legarreta 1999) equivalent to the Mulanguiñeu Formation of Ferrarotti, farther north (44º30´S), consists of pyritic black shales, rich in organic matter, with several sandy and tuffaceous levels, yielding "Pecten aff. P. (Variamussium) coloradoensis Weaver" (=? Kolymonectes weaveri Damborenea, Pliensbachian, cf. Damborenea 1998 and 2002), a microflora with abundant Classopollis and a microplancton of Pleurozonaria and Michrysteridium, an association that Volkheimer considers typically Lower Jurassic. Between this locality and the northernmost outcrops of Chubut (42º30´S) there are more than 250 km, indicating the true size of the basin (Lesta and Ferello 1972). The euxinic facies of this borehole, suggests is evident that the basin extended southwards in the Santa Cruz Province (see Uliana and Legarreta, 1999, their fig. 20), to end as a finger at the 48ºS latitude (Lesta and Ferello 1972). At this latitude, in the Roca Blanca area, the Lower Jurassic consists of continental alluvial plain facies with plants and Estheria sp. (Herbst 1965 and 1968). In summary, the Lower Jurassic basin of extra- Andean Chubut was at least 600 km (42º30´S - 48º S) long and characterised by late Early Pliensbachian to Early Toarcian transgression (Fig. 14).

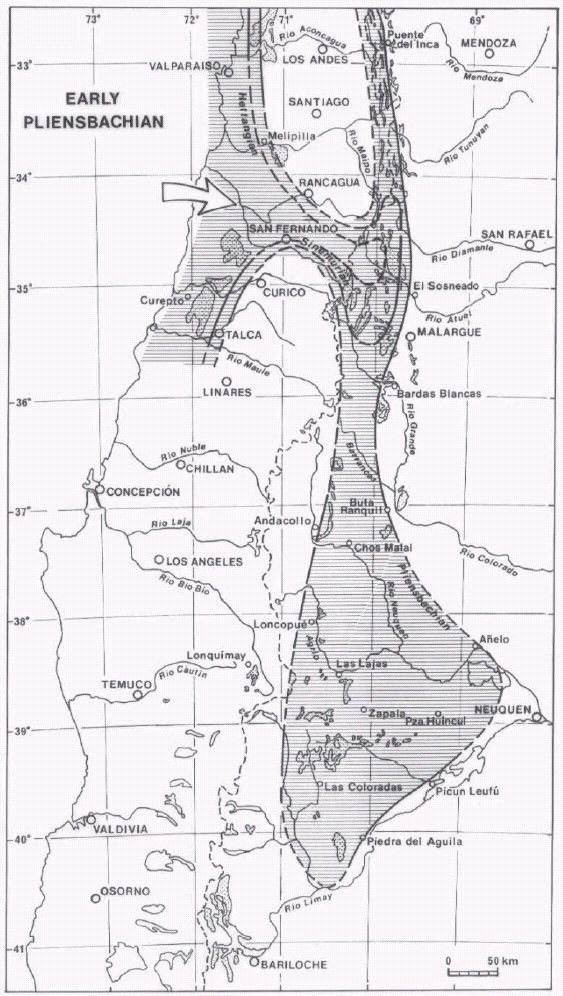

Taking in account that the northernmost outcrops, i.e. Río Lepa (42º38´S), are less than 250 km apart from those of Piedra Pintada (40º17´S), it is difficult to avoid acceptance of a late Early Jurassic connection between the Neuquén and Chubut basins (Lesta and Ferello 1972, cf. Lizuaín 1999). Though alternatively, a connection with the Pacific at the Río Negro latitude has been suggested by Riccardi (1983), all evidence indicates that the transgression, beginning in the Hettangian at the latitude of Alto Atuel, advanced towards the south following a narrow furrow, reaching Neuquén (40º17´S) in the late Early Pliensbachian (Fig. 13), and extra-Andean Chubut in the Late Pliensbachian, before ending at 46º - 47°S (Fig. 14).

Figure 13: Main stages of the Jurassic transgression from Curepto Hettangian Gulf through the Neuquén Basin.

In the Toarcian, the existence of a unique Neuquén-Chubut basin is evident (Fig. 14). Only a northern origin of the Chubut transgression seems possible, considering that the basin margins are relatively well known: the eastern margin by eastward developing conglomeradic and pyroclastic continental facies (Cabeza de Cristiano or Olte Formation) (Herbst 1968, Musacchio and Riccardi 1971, Musacchio 1981). Farther east, in the middle course of the Chubut river, Lower Jurassic conglomerates and Middle Jurassic volcanics rest directly on Precambrian-Paleozoic rocks (Lesta and Ferello 1972; Giacosa and Márquez 1999); the western margin was located in the Patagonian Cordillera where the Middle to Upper Jurassic El Quemado volcanic Complex (Feruglio 1938, Hoffstetter et al. 1957, Féraud et al. 1999) or Ibañez Formation (Niemeyer 1975, Skarmeta 1978) rests on the metamorphic basement of General Carrera and Cochrane lakes (44º30´ - 47º15´S). The southern margin, at 48º latitude, rests on the already mentioned continental facies of Roca Blanca. At the latitude of Malvinas, the results of the DSDP 330 borehole (51ºS, 47º36´W), Leg 36 (Barker et al. 1974), especially of clay mineralogy as well as organic and mineral geochemistry, exclude the opening of the South Atlantic and, therefore, any transgression from the Indic Ocean (Maillot 1983).

Figure 14: Paleogeographic outline of the Neuquen-Chubut Basin during Lower Toarcian. Notice connexion with the Pacific via the Curepto Strait, paleogeographic continuity between Neuquén and Chubut basins, and austral glove-finger ending at 48°S.

In this context are quite important the Lower Jurassic deposits found between Esquel and Nahuel Huapi (43º - 41ºS): the Lepa Formation (Rolleri 1969) south of Leleque (c. 42º 30´S), the Epuyén-Cholila Formation (Miró 1967) in the Epuyen area (42º 15´S), the Piltriquitrón Formation in the El Bolsón region (42ºS; see González Bonorino 1974), the Millaqueo Formation, south of Nahuel Huapi (41ºS; González Bonorino 1974; cf. Lizuaín 1999) and to the north the stromatolite limestones of Villa la Angostura (40º45´S; Dalla Salda et al. 1978). The Early Jurassic age of the volcanicsedimentary succession of the Piltriquitron ridge was confirmed by Lizuaín (1980; see Manceñido and Damborenea 1984) with the record of Early Jurassic - probably Pliensbachian - bivalves and brachiopods. Similarly, González Bonorino (1981) recorded "Myophorella cf. signata Agassiz." in rocks compared with the Piltriquitrón Formation, north of Sierra Chata in the Río Villegas area.

The Curepto Hettangian Gulf: Even if a progressive transgression from the Alto Atuel (34º50´S) towards the south did occur (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980), the Rhaetian-Hettangian age of the marine transgression at this latitude differs from the middle Pliensbachian transgression of the Mercedario area (32º08´S) as well as from the Norte Chico general transgressive scheme, also southwards, implying an initial independence of both basins. Thus one has to look for an oceanic connection at the Atuel latitude. This would have been slightly north of Nacientes del Teno (35º10´S), because this region has a late Aalenian transgression indicating the western margin of the Neuquén Basin at this latitude (Davidson 1971, Davidson and Vicente 1973).

The area of the High Cordillera between 34º45´S and 33ºS, i.e. the headwaters of the Diamante, Maipo, Tunuyan and Tupungato rivers, is precisely the most tectonized part of the Principal Cordillera, where the Jurassic outcrops are almost absent. This is evident in the geological maps San José (33º30´-34ºS), Cerro Tupungato (33º-33º30´S) and Volcán Maipo (34º-35ºS) of the Argentinean slope (Polanski 1964 and 1972, Sruoga et al. 2000), where the roof sheets (Upper Jurassic - Lower Cretaceous) are detached at the top of the Oxfordian gypsum (Aubouin et al. 1973) and do not show the autochthonous base of their succession (except for some Callovian at the base of diapirs). If these resulted from a major eastward overthrust of the thick Kimmeridgian volcanic succession (Río Damas Formation) of the Chilean slope (Vicente 1970 and 1972) there is little hope of finding any record of the Pacific marine ingression at these latitudes. Although on the Chilean and Argentinian High Cordillera at 33º45´S - 34ºS a 450 m thick succession of (?) Early - Middle Jurassic pelites has been reported (Alvarez et al. 1995, 1997 and 1999), the only fossils thus far recorded were Late Bathonian ammonites, found close to the top (400 m).

Important upper Triassic - Lower Jurassic (Hettangian- Sinemurian) marine deposits are present, however, in the coastal area of Chile, at 34º46´ - 35º16´S. The classic outcrops in the south at Río Mataquito, Curepto-Galleco (Muñoz Cristi 1960 and 1973, Thiele 1965, Escobar 1980) and, in the north at Hualañe and Vichuquén-Tilicura (Corvalán and Dávila 1964, Corvalán 1976) occur along a belt more than 60 km long reaching eastwards to 71º46´W, 40 km inland (Corvalán 1982). Furthermore, considering that the upper Triassic (Norian- Rhaetian) is more than 800 m thick in the Curepto area (Escobar 1980) and thins rapidly eastward, to only 300 m in the Hualañe area (Corvalán 1976), while changing from shales to sandstones and conglomerates, one could conclude that the Late Triassic gulf did not pass Hualañe (Fig. 9).

On the other hand, the presence of finely laminated Hettangian shale facies bearing a thin-shelled bivalve benthic fauna which is interbedded with graywackes with graded bedding and slump levels (Cecioni 1970, Escobar 1980) indicating relatively deep sedimentary conditions with turbiditic successions, requires a more eastern position of the coast. This implies the existence at the latitude of Curepto of an important Hettangian gulf, strongly subsident and tectonically unstable, through which the sea penetrated widely towards the east up to the Alto Atuel headwaters (Fig. 13). At the beginning of the early Pliensbachian, the transgression began to spread longitudinally towards the north and south. We propose to name this transgressional gulf the "Curepto Hettangian Gulf". It should be recalled that 265 km north, in the La Ligua area (36º26´S) the transgression passed the 71º13´W only in the Sinemurian.

Conclusion

The western border of the Andean Retroarc Basin of Central Andes thus appears to be dominantly controlled during the Jurassic by the tectonic and magmatic activity of the arc. Importance of volcanoclastic and volcanic input in sediments of this insular border leaves no doubt about the reality and magnitude of this activity. The observed characteristics such as thick volcanic series forming the arc indicate that main volcanic activity was above sea level. Whereas notable alongstrike continuity and width of the arc proves that, at first sight, it represented a wide barrier to the direct ingression of waters from the open Pacific. In such a way that the Andean Retroarc Basin can be looked as a typical barred basin.

In that framework, evidence of longitudinal changes in age of transgressions, when checked in the most axial part of the basin, allows the localisation of two major straits through the arc: the first in northern Chile at latitude of Taltal (25°15'S) and the second in central Chile at latitude of Curepto (35°S). From which Pacific waters entered and flooded gradually the rifted retroarc and progressed lengthwise at the same time northward and southward as a narrow furrow. Both straits initiated in the upper Triassic and extended during the Hettangian. At the beginning, the just created Tarapacá and Aconcagua-Neuquén basins were isolated, and became connected in the middle Pliensbachian giving birth to a continuous elongated retroarc basin from central Chubut to northern Perú. Meanwhile, the initial zone separating both basins as Norte Chico Isthmus is looked as a zone with positive tendency where transgression was belated.

On the scale of the whole Andean margin, two more straits must be mentioned by which Pacific waters have penetrated and flooded the future Andean Basin. In northern Peru was the "Olmos Late Triassic Gulf" (6ºS) and in Colombia the "Ibagué Late Triassic Gulf" (Geyer 1973 and 1979), which produced the Norian marine deposits of the Payandé Formation in the Tolima basin. Thus, we may assume that from the beginning of the late Early Pliensbachian all basins were connected and that form then an important continuous furrow extended for more than 4.400 km, with a width of about 25 to 50 km, except for Neuquén where it was more than 200 km wide at 38ºS (Fig. 12). It should be recognised that this remarkable continuity and narrowness of the Andean basin leaves little doubt about its tectonic control.

Significant in this context are the turbiditic and olistostrome levels recorded in the Triassic - Sinemurian of the Atuel area (Riccardi et al. 1988) and Upper Pliensbachian of the Cordillera del Viento and Sierra de Chacay Co (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980). These authors relate these deposits to synsedimentary faults active during Neuquen basin subsidence. Active subsidence would also explain the existence of early Toarcian, deep-turbiditic deposits (Los Molles Formation) over a great part of southern Neuquén. Sometimes these deposits are remarkably thick such as in the Barda Colorada Este borehole, 30 km south of Plaza Huincul, where they were penetrated for more than 2500 m with typical deep-turbiditic facies (Hinterwimmer and Jauregui 1984).

A similar situation, involving marked subsidence can be observed at the latitude of the Tarapacá basin in the Domeyko Cordillera where, beginning with the Pliensbachian, there are fine laminated micritic facies with radiolarians, reminiscent of abyssal-plain deposits. These facies become enriched in turbiditic sandstones passing into a true psamo-pelitic flysch with olistoliths and slumps (Vicente et al. 1985). Another area with strong subsidence is located at the latitude of Cerro Longacho (20º23´S), north of Pica, where Sinemurian facies consist of fine pyroclastic turbidites with abundant siliceous spicules and radiolarians.

The Arequipa basin also is marked by extensive early subsidence, as indicated by Sinemurian calcilutites with slumps and the turbidites with encrinites of the Lagunillas Formation in the Puno area (Vicente, 1981). Furthermore, near Arequipa, at the basin´s insular margin, true synsedimentary faults and intraformational unconformities related to block faulting have been recorded (Vicente et al. 1982).

The pre-transgressive continental deposits remain, nevertheless, the best evidence for the extensive tectonism predating basin formation. It is indicated by the highly irregular geometry and abrupt thickness changes of the so-called "Precuyan" cycle in Neuquén and southern Mendoza (Gulisano 1981, Gulisano et al. 1984, Digregorio et al. 1984, Uliana et al. 1989, Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleiming 1995 ( fig. 7 and 8). This "cycle" consists of Rhaetian-Lower Jurassic alluvial, fluviatile and lacustrine deposits with high volcanic and pyroclastic content in the El Freno (Stipanicic and Bonetti 1970, Volkheimer 1970) and Remoredo (Stipanicic and Mingramm in Groeber et al. 1952, Stipanicic 1966) formations in southern Mendoza, Chacaico (Parker 1965), Sañicó (Galli 1953, Stipanicic 1967), Piedra del Aguila (Ferello 1947) and other areas in western Neuquén, These sequences are interpreted as the initial fillings of topographic highs and lows due to rotated blocks, located within the low, cratonic margin with an extensive regimen of associated volcanism. This situation is evident at the latitude of Bardas Blancas (Gulisano 1981) where a graded transgression has been reported and in southern Neuquén (Gulisano et al. 1984 where these structures occur at the base of the transgression.

Even if an analysis of the synsedimentary fracturing is required, it is clear that fracturing controlled the configuration of the Neuquén basin margins (Mombru and Uliana 1978). Thus it comes as no surprise that there is some coincidence (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980) between some inferred faults and major structural lineaments such as those of Añelo and Río Limay (Ramos 1978, 1998), which give the basin its triangular shape.

All lines of evidence are, therefore, in agreement that a somewhat subsident Andean Basin area originated by extension, behind an active volcanic arc, and was related to subduction of the proto-Pacific at the Gondwana western margin (Uliana et al. 1989). This geotectonic setting excludes any intracontinental rift and leads to accepting the idea of an "aborted-marginal" retroarc basin whose basement remained sialic (Vicente 1984; Digregorio et al. 1984, etc.).

Works cited on the text

Alvarez, P.P., 1996 a. Bioestratigrafía del Jurásico inferior de la Cuenca de La Ramada, Alta Cordillera de San Juan (Argentina). Revista Española de Paleontología 11(1): 35-47, Madrid. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P.P., 1996 b. Jurassic ammonite assemblages of the Principal Cordillera of San Juan, Argentina. En A.C. Riccardi (ed.) Advances in Jurassic Research, GeoResearch Forum 1-2: 45-54, Transtec Publications Ltd., Zurich. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P.P., 1996 c. Los depósitos triásicos y jurásicos de la Alta Cordillera de San Juan. Geología de la Región del Aconcagua, Provincias de San Juan y Mendoza. Dirección Nacional del Servicio Geológico, Anales 24: 59-137, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P. 1997. Evolución estratigráfica y tectónica del Jurásico de la Alta cordillera de San Juan. Doctoral thesis, Universidad de Buenos Aires, (unpublished), 375 p. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P.P., Benoit, S.V. and Ottone, E.G., 1995. Las Formaciones Rancho de Lata, Los Patillos y otras unidades mesozoicas de la Cordillera Principal de San Juan. Asociación Geológica Argentina, Revista 49(1-2) (1994): 123-142, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P., Aguirre Urreta, M.B., Godoy, E. and Ramos, V.A., 1997. Estratigrafía del Jurásico de la Cordillera Principal de Argentina y Chile (33°45´-34°S). 8° Congreso Geológico Chileno, Antofagasta, 1: 425-429. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P., Godoy, E., and Giambiagi, L., 1999. Estratigrafía de la Alta Cordillera de Chile Central a la latitud del Paso Piuquenes (33º 35´S). 14° Congreso Geológico Argentino (Salta), Actas 1: 55. [ Links ]

Alvarez, P.P., Godoy, E., Aguirre-Urreta, M.B., 1996. Jurásico marino de la Alta Cordillera de Chile Central, Región Metropolitana. 13° Congreso Geológico Argentino, Buenos Aires, 5: 181. [ Links ]

Arabaz, W.J. 1971. Geological and geophysical studies of the Atacama Fault Zone in Northern Chile. Doctoral thesis, California Institut of Technology, Pasedana, 263 pp. [ Links ]

Ardill J., Flint S., Chong G. & WilkeH. 1998. Sequence stratigraphy of the Mesozoic Domeyko Basin, northern Chile. Journal of the Geological Society, London, 155: 71-88. [ Links ]

Aubouin, J., Borrello, A.V., Cecioni, G., Charrier, R., Chotin, P., Frutos, J., Thiele, R. Vicente, J-C., 1973. Esquisse paléogéographique et structurale des Andes Méridionales. Revue de Géographie Physique et de Géologie Dynamique, Paris, 15(1-2) : 11-72. [ Links ]

Baeza, L.G., 1976. Geología de Cerritos Bayos y areas adyacentes entre los 22°30'-22°45' latitud sur y los 68°55'-69°25' longitud oeste, II región - Antofagasta, Chile. Tesis Universidad del Norte, (unpublished), 155 p., Antofagasta. [ Links ]

Baeza, L.G., 1979. Distribución de facies sedimendarias marinas en el Jurasico de Cerritis Bayos y zobas adyacentes, Norte de Chile. 2° Congreso Geológico Chileno (Arica), Actas 3, H45-H61. [ Links ]

Barker, P., Dalziel, I.W., et al., 1974. Evolution of the southwestern Atlantic ocean Basin : results of Leg 36, Deep Sea Drilling Project. Initial Report DSDP, 36: 993-1014. , Washington. [ Links ]

Behrendsen, O., 1891-92. Zur Geologie des Ostabfalls der argentinischen Cordillere. Zeitsch. Deutchen Geologischen Gesselshaft, Berlin, 43(1891): 369-420, 44(1892): 1-42. [ Links ]

Blasco, G., Levy, R., and Nullo, F., 1979. Los Amonites de la Formación Osta Arena (Liásico) y su posición estratigráfica - Pampa de Agnia - (Provincia del Chubut). 7° Congreso Geológico Argentino (Neuquén), Actas 2: 407-429. [ Links ]

Blasco, G., Levy, R., and Ploszkiewicz, V., 1980. Las calizas toarcianas de Loncopán, Depto. Tehuelches, Provincia del Chubut, Republica Argentina. 2° Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía y 1° Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología, Actas 1: 191-200, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Buhler, M., Perez, D.J., and Ramos, V.A., 1996. El Jurásico de las Nacientes del Río Colorado, Departamento de San Carlos, Provincia de Mendoza. 13° Congreso Geológico Argentino y 3° Congreso de Exploración de Hidrocarburos, 5: 183, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Burckhardt, C., 1902. Le Lias de la Piedra Pintada (Neuquen), 3. Sur les fossiles marins du Lias de la Piedra Pintada avec quelques considerations sur l'âge et l'importance du gisement. Revista del Museo de La Plata, 10: 243-249, La Plata. [ Links ]

Cecioni, G., 1960. La zona con Psiloceras planorbis en Chile. Escuela de Geología, Santiago, 1(1), 19 p. [ Links ]

Cecioni, G., 1961. El Titónico inferior marino en la provincia de Tarapacá y consideraciones sobre el arqueamiento central de los Andes. Escuela de Geología, Santiago, 1(3), 28 p. [ Links ]

Cecioni, G., 1970. Esquema de Paleogeografía chilena. Editorial Universitaria S.A., Santiago, 143 p. [ Links ]

Chong, G. 1973. Reconocimiento geológico del area Catalina-Sierra de Varas y estratigrafía del Jurásico del Profeta. Doctoral thesis, Universidad de Chile, (unpublished), 294 pp. , Santiago. [ Links ]

Chong, G., 1976. El sistema jurásico en la Cordillera de Domeyko (Chile) entre 24°30' y 25°30' de latitud sur. 2° Congreso Latinoamericano de Geología, Caracas, 2: 765-785. [ Links ]

Chong, G., 1977. Contribution to the knowledge of the Domeyko Range in the Andes of Northen Chile. Geologische Runschau, Stuttgart, 66(2): 374-404. [ Links ]

Chong, G., Hillebrandt, A., 1985. El Triásico preandino de Chile entre los 23°30' y 26°04' de lat. sur. IV° Congreso Geológico Chileno, Actas 1: 162-210, Antofagasta. [ Links ]