Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina

versão impressa ISSN 0004-4822versão On-line ISSN 1851-8249

Rev. Asoc. Geol. Argent. v.61 n.3 Buenos Aires set. 2006

Dynamic Paleogeography of the Jurassic Andean Basin: pattern of regression and general considerations on main features

Vicente, J-C.

Laboratoire de Tectonique, Université P. & M. Curie-Paris 6 Case 129, F 75252 PARIS Cedex 05, France. E-mail: vicente@lgs.jussieu.fr

ABSTRACT

Following examination of the evolution of the Jurassic Andean retroarc basin at a global scale for the Central Andes, this paper analyses the pattern of the regressive process, and discusses some general features concerning Andean Jurassic Paleogeography. The early Upper Jurassic regression obeys to an exactly reverse pattern as the one evidenced for the Lower Jurassic transgressive process. Sectors with late transgressions become those with early regressions while those with early transgressions show later regressions. This fact may indicate that the Norte Chico Isthmus (29°S to 30°30'S) was a precociously emerged zone from the Bajocian. This carries again a split up between the Tarapacá and Aconcagua-Neuquén basins until their complete drying up in the Late Oxfordian following their restricted circulation. This evaporitic late stage presents great analogy with the Mediterranean «Messinian crisis» and gives evidence of a general tectonic and magmatic control on the straits. The local transgressions observed on the cratonic margin of the central part of these shrinking basins were due to shifting of water masses resulting from the regressive process on the northern and southern margins.

Comparison between the main stages of transgression and regression allows some quantification concerning velocities of displacement of coastlines, specifically lengthwise. The permanence of paleogeographic and structural features over the time argues for an indisputable tectonic heritage. In the dynamic framework of this typical barred retroarc basin where arc magmatic activity has contributed considerably to variation on sediment supply and changing bathymetry of the seaways connecting with the Pacific Ocean, evidence for an assumed global eustatic cycle remains questionable or very subordinated.

Keywords: Jurassic; Retroarc basin; Trangression; Regression; Paleogeography; Andes.

RESUMEN

Paleogeografía dinámica de la cuenca jurásica andina: Formas de regresión y consideraciones generales sobre los rasgos principales. Con posterioridad al exámen de la evolución de la cuenca andina jurásica de retroarco a una escala global para los Andes Centrales, este trabajo analiza el diseño de los procesos regresivos y discute algunos rasgos generales concernientes a la paleogeografía jurásica de los Andes. La regresión jurásica superior temprana obedece a un diseño exactamente opuesto al evidenciado para los procesos transgresivos del Juràsico Inferior. Los sectores con transgresiones tardías son aquellos que tienen regresiones tempranas, mientras aquellos con transgresiones tempranas muestran transgresiones más tardías. Este hecho puede indicar que el itsmo del Norte Chico (29ºS a 30º30'S) fue una zona precozmente emergida desde el Bayociano. Esto produce nuevamente una separación entre las cuencas de Tarapacá y la de Aconcagua-Neuquén hasta su completa desecación en el Oxfordiano superior continuando una circulación restringida. Este estadío póstumo evaporítico presenta una analogía grande con la crisis messiniana del Mediterráneo y aporta evidencia para un control tectónico y magmático en los estrechos. Las transgresiones locales observadas en el margen cratónico de la parte central de estas cuencas en reducción fueron debidas a la migración de masas de agua resultantes del proceso de regresión en los márgenes norte y sur.

La comparación entre las principales estadios de transgresión y regresión permite alguna cuantificación concerniente a las velocidades de desplazamiento de las líneas de costa, en especial si longitud. La permanencia de rasgos paleogeográficos y estructurales a través del tiempo argumenta a favor de una herencia tectónica indisputable. En un marco dinámico de estas cuencas de retroarco con barreras donde la actividad del arco magmático ha contribuido considerablemnete a la variación del suministro de sedimentos y a la batimetría cambiante de los paso de conexión con el Océano Pacífico, la evidencia para asumir un ciclo eustático global permanece cuestionable o muy subordinada.

Palabras clave: Jurásico; Cuenca retroarco; Trangresión; Regresión; Paleogeografía; Andes.

INTRODUCTION

During the early Late Jurassic, a very important regression occurred in the Andean retroarc Basin between extra-Andean Patagonia (43°45'S) and Northern Chile (21° 45'S). This regression resulted first in a complete drying and emersion, and then, mainly in the Kimmeridgian, in the deposition of continental red beds. So, the purpose of this paper is to indicate the main stages of this regression, to examine its consequences on the dynamic of water masses and to see to what extent the seaways opened through the arc in the Early Jurassic took part in that last process. The similarity of this regressive process with the transgressive one raises the problem of the permanence and inheritance of paleogeographic and structural features. Furthermore, the significance of these straits as potential filters for that barred basin, and in the degree of faunal endemism, and in the record of global eustatic cycles in a very active magmatic setting, will be analyzed. Finally, the obvious southward continuity of the magmatic arc through the North Patagonian Cordillera, together with the paleogeographic connections between the Chubut and Neuquén basins will be used to reject the Dorsal del Chubut assumption. Instead it will be accepted the notion of a North Patagonian Transition between the Andean and the Magallanes systems.

As for the transgressive scheme discussed in the previous paper (Vicente 2005), we will follow the same reasoning at basinal scale, i.e. the starting point will be again our study area of the High Cordillera of San Juan and Mendoza (31°30'-33°S), and then the discussion will be progressively extended to the adjacent northern and southern areas.

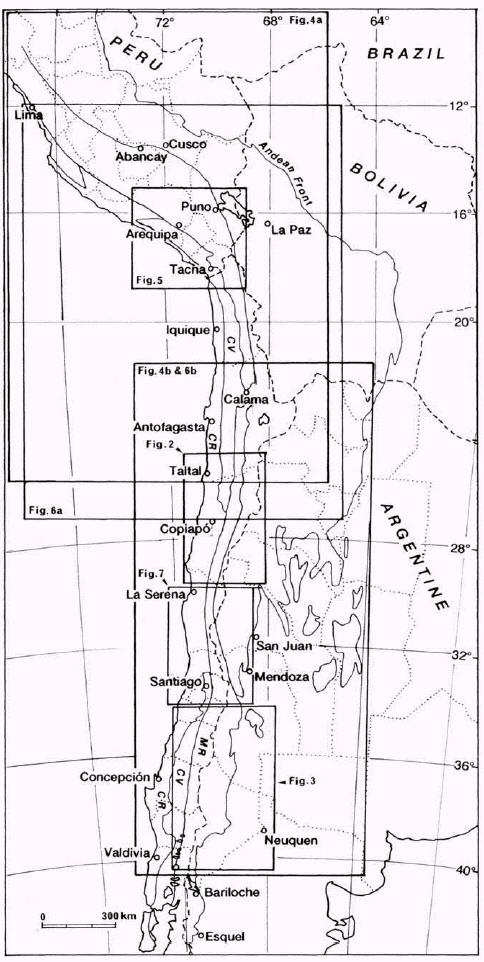

Figure 1 depicts the main morphostructural Andean units the names of the principal geographic regions, and the location of paleogeographic maps included in this paper. These maps are presented in the stratigraphic order to provide a most dynamic and simple paleogeographic view, although discussion in the text reasoning will lead often to introduce them in a different order.

Figure 1: Locality map showing main Andean morphostructural units of interest and areas covered by paleogeographic maps included in this paper. CR=Coast Range; CV=Central Valley; MR=Main Range (=Principal or Western Cordillera); Limits of Provinces (=Departments or Regions) of Argentine, Chile and Peru are also indicated.

EVOLUTION OF THE ANDEAN BASIN DURING THE MIDDLE AND EARLY LATE JURASSIC: THE REGRESSIVE PROCESS

Latitude of study area (31°30' –33°S)

The regression along the basin axis is characterized by the presence of thick Upper Oxfordian evaporites (Principal Gypsum=Auquilco Fm.) (cf. Fig. 4 of part I). The underlying bituminous shales of restricted facies have yielded, in the Alma Negra area, an "Idoceras" (det. Covacevich) fauna indicating the upper part of the Upper Oxfordian. To the north the last outcrops are at Portezuelo Yesito (31º36'S) (see Fig. 7). Farther north, the area of Norte Chico (31º and 26ºS), is characterized by the absence of evaporites and an early regression (Jensen and Vicente 1979).

North

Norte Chico Cordilleran area (31º - 26ºS)

At the latitude of Los Pingos (30º45'S) the regression was supposed to have occurred in the early Callovian (Rivano 1975) in facies of red sandstones with ripple marks, drying cracks, gypsum nodules and littoral conglomerates, with rare "Macrocephalites sp., Eurycephalites cf. rotundus (Tornq.), Kamptokephalites sp." and Vertebrate remains. However, the uppermost ammonites present in the Mina Los Pingos area were later identified by Riccardi (cf. also Hillebrandt 2002, p. 57) as Late Bajocian Megasphaeroceras spp. These facies represent the transition to the Upper Jurassic red continental successions. It is only at 28º15'S, in the Manflas area, southeast of Copiapó, where the presence of marine lower Callovian has been assumed on the basis of 3-4 m thick marine limestones overlying red sandstones and marine Upper Bajocian with ammonites (Hillebrandt 1973 and 1977, Jensen et al. 1976). Definite Lower Callovian with ammonites is present at the latitude of Salar de Pedernales (c. 26º15'S) (Riccardi and Westermann 1991).

In the intervening area, the distance of about 180 km (2º30') between Elqui High Cordillera to the Tránsito Cordillera, the regression is mainly Bajocian (Fig. 2). This can be inferred from the works of Hillebrandt (1970, 1971, 1973 and 2002), Westermann and Riccardi (1972 and 1979) and Hillebrandt and Westermann (1985) although they gave little attention to age of the regression. In these facies of sandy calcarenites, sandstones and red pelites, rich mainly in bivalves that grade upwards into Upper Jurassic continental tuffs and volcanics, Bajocian faunas are present in the areas of Doña Ana, Portezuelo de la Punilla and Quebrada Pinto (Hillebrandt 1973). But it is only at the latitude of Quebrada Chanchoquin (28º45'S) that the Lower Bajocian (Singularis and Giebeli Zones = Laevisucula and Sauzei Zone) is clearly indicated by Pseudotoites sphaeroceroides (Tornq.) and Sonninia espinazitensis Tornquist and Emileia giebeli (Gottsche) (Hillebrandt 2002).

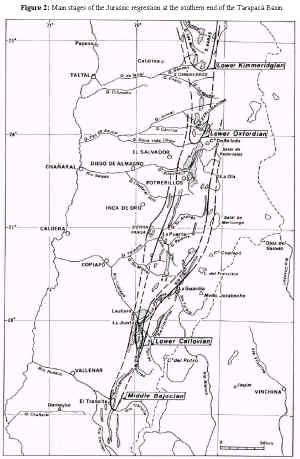

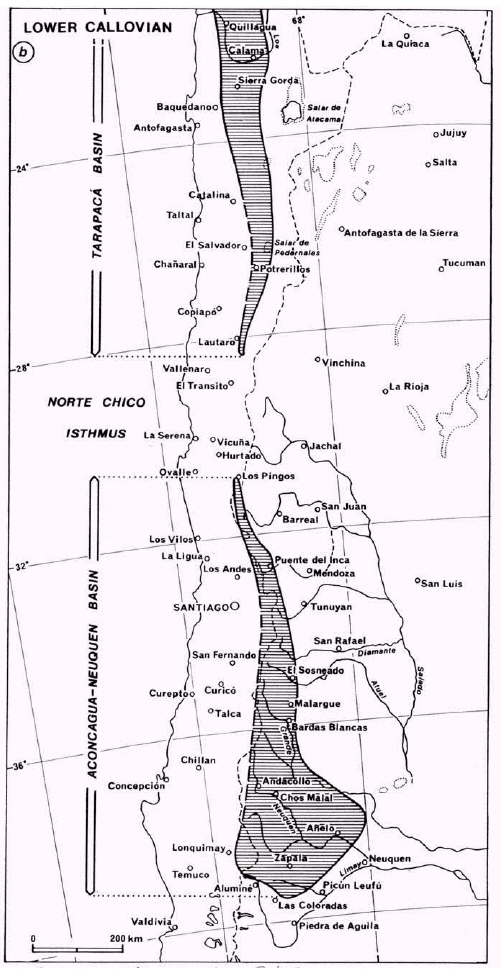

Figure 2: Main stages of the Jurassic regression at the southern end of the Tarapacá Basin.

On the other hand, in the Manflas area the Humphriesianum Zone is well established by Chondroceras cf. defontii (McLearn), and the Upper Bajocian by Lupherites dehmi (Hillebrandt), L.(?) chongi (Hillebrandt), Duashnoceras cf. caracolense (Westermann & Riccardi), D. chilense (Hillebrandt), D. profetaense Hillebrandt, Teloceras (?) sp., Stephanoceras spp. and Megasphaeroceras sp (Hillebrandt 1970, 1977 and 2002, Jensen 1976; Jensen and Vicente, 1976; Westermann and Riccardi, 1979; Riccardi and Westermann, 1991). The thin oolitic limestone with echinoids that is at the top of the succession was dated as early Callovian (Hillebrandt 1973, Jensen 1976).

Farther north, the Callovian is well developed (Fig. 2): first as a level of pink sandy limestones with bivalves at the latitude of Río Figueroa and Quebrada La Tola (27°14'S) (Hillebrandt 1973, Hillebrandt and Westermann 1985), and immediately to the south at Quebrada Paipote (Vega Redonda) (27°09'S) with greenish, and somewhat sandy, oolitic calcarenites, rich in volcanic material and bivalves, brachiopods, echinoids and Solenopora sp. This last facies is especially well exposed in the area of Quebrada San Andrés (27°S) (Cisternas and Vicente 1976, Cisternas 1977) and Chañaral Alto (26°40'S) (Oviedo 1977) where "Reineckeia brancoi" (Steinmann) ) (=? Rehmannia brancoi) suggests Early Callovian (Harrington 1961, García 1967, Hillebrandt 1970, Pérez 1978, Riccardi and Westermann 1991). At this latitude, the basin had a width of about 65 km, taking into account a tectonic shortening of about 30% and that the eastern basin margin reached 69°11'W in the La Ola area (Cisternas 1977 and 1979).

Cordillera Domeyko area (25º40'- 24º30'S)

Marine Oxfordian begins at the southern end of this area (Fig. 2). At the latitude of Sierra Exploradora (25º40'-25º50'S), the succession is only Lower Oxfordian (Davidson and Godoy 1976, Jensen et al. 1976). But immediately to the north, beginning at Quebrada Incaguasi (25º36'S), the marine sedimentation continued almost to the end of the Oxfordian (Hillebrandt 1970, Chong 1973, 1976 and 1977, Naranjo and Covacevich 1979, Gygi and Hillebrandt 1991), ending with evaporites as in the Neuquen basin (Principal Gypsum). At the latitude of Quebrada Incaguasi, Hillebrandt (1970), Gygi and Hillebrandt (1991) and Hillebrandt and Gröschke (1995) identified the Bimmamatum Zone in the upper levels by Lithacosphinctes desertorum (Stehn), Orthosphinctes cf. tiziani (Oppel), Larcheria aff. gredingensis (Wegele), Idoceras cf. neogaeum Burckhardt and Ochetoceras mexicanum (Burckhardt).

At the latitude of Sierra Candeleros (25º25'S), Naranjo and Covacevich (1979), also noted the probable existence of the Planula Zone, based on the association of Idoceras sp. and Physodoceras (?) sp. Chong (1973, 1976 and 1977), on the other hand, suggested that the upper levels of the marine succession belong in the lower Kimmeridgian, based on the presence of "Rasenia (Prorasenia) sp., Simaspidoceras sp., Perisphinctes (Virgatosphinctes) sp. and Aulacosphinctoides" in Quebrada El Profeta of Sierra de Varas (24º59'S). Presence of uppermost Oxfordian to Lower Kimmeridgian in this region, with Cubaspidoceras cf. caribeanum Myczynski and Orthaspidoceras sp., was confirmed by Förster and Hillebrandt (1984; see also Gygi and Hillebrandt 1991). Likewise, farther north, at the latitude of Cerritos Bayos (22º35'S), "Aspidoceras (Orthaspidoceras) sp., Subneumayria (?) sp. and Rasenia sp." were recorded by Baeza (1976; cf. Förster and Hillebrandt 1984), and Cubaspidoceras sp. by Gygi and Hillebrandt (1991) in levels underlying the evaporites, would indicate the Lower Kimmeridgian (Covacevich, written comm. 1975). Summing up, these data indicate the mainly Early Kimmeridgian age of the Cordillera Domeyko evaporites (Fig. 2).

Finally, we stress the typically Upper Oxfordian features, i. e. pre-evaporitic facies of finely laminated bituminous shales, indicating a change to stratified water conditions (Busson, 1978) with, stagnant, hypersaline bottom waters. These anaerobic conditions explain the remarkable preservation of fishes (Biese 1961, Arratia et al. 1975a and 1975b, Baeza 1976 and 1979), marine reptiles (Biese 1961, Chong 1973 and 1977) and decapod crustaceans (Chong and Förster 1976, Förster and Hillebrandt 1984).

Area of Antofagasta and Tarapacá Precordillera

Farther north, the marine Oxfordian continues with the same facies of finely laminated black shales at least as far as the latitude of Pisagua (19º35'S). It suffices to remember the extensive belt along the Precordillera of Antofagasta and Tarapacá from Sierra Moreno up to Huatacondo, which García (1967) named Aquiuno Formation, later (Maksaev 1978) included in the Quinchamale Formation (cf. Ramírez and Huete 1981, Skarmeta and Marinovic 1981). Thus, in the eastern slope of Sierra Moreno (21º43'S), the marine upper levels of the Quinchamale Formation (Maksaev 1978) yielded a diverse Perisphinctes assemblage dating these levels as Oxfordian. Furthermore, marine sedimentation ends at this latitude in the form of a notable evaporite level, the last important occurrence at this meridian (68º56'W). García (1967) dated his Aquiuno Formation as (Late) Oxfordian on the bases of ammonites found in Quebrada de Arca (21º43'S), Quebrada Sama (21º30'S), Quebrada Sipuca-Quehuita (21º12'S; see also Vergara 1978), and Quebrada Mani (21º05'S; see also Muñoz Cristi 1973). Whilst Skarmeta and Marinovic (1981) recorded Gregoryceras sp. and Perisphinctes s.l. (Middle Oxfordian), in the upper part of the marine member of the Quinchamale Formation at the western slope of Sierra Moreno. This has been confirmed by Gröschke and Prinz (1986) and Gröschke and Wilke (1986).

At the latitude of Quebrada Huatacondo (20º55'S), where García (1967) defined the Aquiuno Formation, the presence of Perisphinctes sp. supports an Oxfordian age. The formation consists of finely laminated, calcareous turbidites, with micrites containing spicules alternating with redeposited encrinites. The general analyses of this belt by Garcia (1967) indicated a remarkable northwards increase of the marine features in this formation. This, together with the ending of the evaporites at about 21º43'S and, farther north, the presence of only a few thin (maximum 10 cm) lenticular intercalations, enables us to locate the most restricted part of the basin southernmost between Cerritos Bayos and Sierra de Varas. At the latitude of Cerro Santa Elena (23º43'S) in the Sierra Moreno, the gypsum is less than 20 m thick (Maksaev 1978); at the latitude of Cerritos Bayos (22º30'S) it reaches 60 m (Baeza 1976); exceeds 100 m in the Quebrada Los Yesos, south of Caracoles (23º06'S) (Chong 1973); and is reduced to 50 m at the latitude of Quebrada Sandón of Sierra de Vaquillas Altas (25º17'S); before disappearing immediately to the south. In Sierra Candeleros and Sierra Santa Ana, the regression has no evaporites (Naranjo and Covacevich 1979). Summing up, the Early Kimmeridgian evaporitic basin of the Chilean Norte Grande extended from 21º40'S to 25º20'S, i. e. a distance of ca. 400 km.

Finally, north of Huatacondo are three more important outcrops of marine Oxfordian, the Chacarilla Formation (20°38'S) south of Pica and the Duplixa Formation in the Juan de Morales area (20º05'S) respectively described by Galli and Dingman (1962) and Galli (1968) that yielded diverse Perisphinctes and Arisphinctes (?), and the Pachica Formation at the latitude of Tarapacá (19º51'S) with Perisphinctes species (Perez 1961, Espiñeira et al. 1984; Covacevich 1985) together with Diceras sp. (Rudista) and "Inoceramus galoi" [= ? Retroceramus galoi (Boehm)]. In contrast to the southernmost facies, these formations have well oxygenated littoral facies with important quartzite levels at the top. Moreover, as anticiped by Cecioni (1970) the Pachica area has provided good paleoslope indicators from the east and southeast.

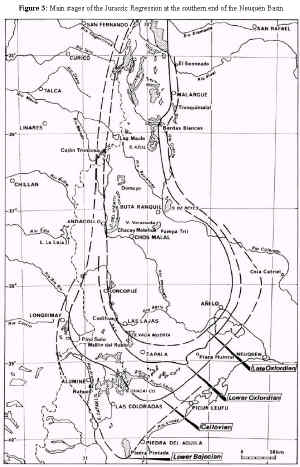

Figure 3: Main stages of the Jurassic Regression at the southern end of the Neuquén Basin.

Coastal area of Iquique and Arica (20º20' - 18º30'S)

These last outcrops are interesting because farther west, on the eastern slope of the coastal chain of Iquique and Pisagua, is a second belt of marine Oxfordian, belonging in fact the western basin margin. Thus it is possible to estimate the width of the Oxfordian basin at this latitude to about 75 km (see Fig. 6a). The sediments consist of the upper levels of the Huantajaya Formation (García 1967, Thomas 1970, Silva 1972 and 1976), which, from Estación Godo (20º20'S) to Cerro Atajaña (19º18'S), form a subcontinuous belt of outcrops characterized by facies of shales and finely laminated black marls interbedded at the top with thin gypsum beds. An ammonite fauna with Perisphinctes, Orthosphinctes, Arisphinctes, Euaspidoceras, and Gregoryceras was dated as Upper Oxfordian at the latitude of Iquique (Thomas, 1970) and, overlain by probably Kimmeridgian with Progeronia (?) and Dorsoplanites (?).The Gregoryceras were later (Gygi and Hillbrandt 1991) included in G (G.) chongi Gygi and Hill. and G. (G.) aff. riazi, Middle Oxfordian. At the latitude of Quebrada Tiviliche, the presence of "Perisphinctes" (Orthosphinctes) sp., Kinkeliniceras sp. cf. sornay Agrawal and Metapeltoceras sp." could indicate the Upper Oxfordian (Silva 1972 and 1976). On the other hand, following Thomas (1970) we doubt the old record by Cecioni (1961) of Lower Tithonian Virgatosphinctes from these levels. Revised sections by Kossler (1998) and Hillebrandt et al. (2000) confirm that there is no evidence for Jurassic sediments younger than Oxfordian age in the northern part of the Chilean Coastal Cordillera.

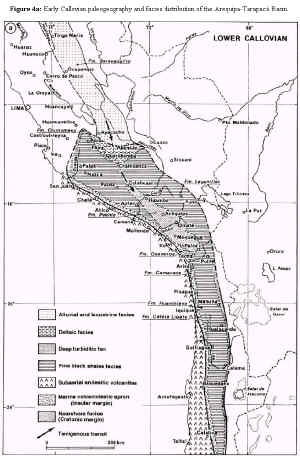

Of additional interest is the westward facies change of Bajocian and Callovian levels of the Huantajaya Formation into a thick succession (Caleta Ligate Formation) of volcanic sandstones and breccias with graded bedding (pyroclastic turbidites) and interbedded submarine andesitic flows (Silva 1976, his figure 4). This indicates the proximal presence to the west at that time of a volcanic arc (Figs. 4a and 4b), what confirm some paleoslope indicators (Cecioni 1970, his figure 5).

Figure 4a: Early Callovian paleogeography and facies distribution of the Arequipa-Tarapacá Basin.

Figure 4b: Isolation of the Aconcagua- Neuquén and Tarapacá basins in the Early Callovian following the emergence of the Norte Chico Isthmus.

This marine Oxfordian belt extends subcontinuously northward up to Arica (see Fig. 6a) and is called Los Tarros Formation (Cecioni and García 1960, Salas et al. 1966, Tobar et al. 1968). It consists of finely laminated black shales with calcareous concretions yielding Perishpinctes (Orthosphinctes) gottschei Stehn, P. boehmi Steinm., Ochetoceras canaliculatum (v. Buch), Gregoryceras sp. and Progeronia (?) sp., a typically (Upper) Oxfordian assemblage (although the last genus could be Lower Kimmeridgian). The specimens of Gregoryceras were later (Gygi and Hillebrandt 1991) referred to G. (G.) aff. riazi (De Grossouvre) and G. (G.) sp., Middle Oxfordian.

Localized between the localities described above are the outcrops of Quebrada Chiza (19º 12' S), east of Cuya. They rest on the Cuya volcanics of the Camaraca Formation (Salas et al. 1966, García 1967) and are overlain with weak unconformity by Upper Jurassic continental conglomerates of the Atajaña Formation. The Chiza Formation yielded only Callovian "Macrocephalites sp. and Reineckeia sp." (García 1967), but their presence at lower levels make the Oxfordian probable. This is the case immediately to the south at the latitude of Cerro Atajaña, where the continental succession rests on black shales with the (Upper) Oxfordian Perisphinctes harringtoni Leanza (Cecioni and García 1960). This unconformity also caused the Atajaña Formation to rest on different rocks (García 1967), such as on Andean diorites intruding into Jurassic lavas at the latitude of Quebrada Camarones (19º04'S), and on the Camaraca Formation lavas (Callovian) at the latitude of Quebrada Victor (18º46'S). The presence of some clasts of Andean diorite and of Jurassic limestones in the basal conglomerate (Cecioni and García 1960) confirms the importance of paleoarc erosion. Thus the coastal area differs clearly from the Precordilleran area, mentioned above, where the change to Kimmeridgian red beds is gradual.

It remains to mention several outcrops in the Arica interior that are assigned to the Los Tarros Formation (Salas et al. 1966) in the middle course of Quebrada Azapa (Livilcar area) and of Rio Lluta (Millune and Larancagua area). The former outcrop has shales with calcareous intercalations bearing Perisphinctes, the second shales and quartzites (Montecinos 1963) in Peruvian facies (Vicente 1981). The survey done, together with Davidson, Fuenzalida and Harambour (December 1984) showed:

- In the Livilcar area, black calcilutites and shales with Aspidoceratidae (det. Covacevich) and Perisphinctes sp. (Muñoz et al. 1988) are finely laminated, with thin silt levels, suggesting distal turbidites of abyssal plain (Td, et, ep). The facies is reminiscent of the lower member of the Ataspaca Formation of Tacna (Salinas 1986).

- In the Millune area (middle course of Rio Lluta, heigth 1350 m) is a recurrence of finely laminated black shales and siltstones with Posidonia.sp. The succession (Millune Formation of Montecinos 1963) changes rapidly upwards into sandstones, producing negative sequences typical of distal turbiditic lobules before passing into volcanic arenites and breccias of the overlaying Saucine Formation. The Millune Formation appears to be similar to the middle to upper members of the Peruvian Ataspaca Formation, whilst the volcaniclastics of the Saucine Formation indicate the facies of the Guaneros Formation of southern coastal Peru (Bellido and Guevara 1963, Roperch and Carlier 1992), i. e. influx of the coastal marine arc (Fig. 4a).

Southern Peru (18°- 16°S)

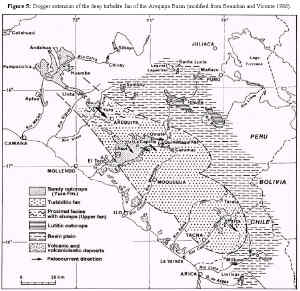

In contrast to the Chilean Norte Grande, where marine sedimentation ended consistently at the end of the Oxfordian and passed into a characteristic continental episode, the marine sedimentation of southern Peru was continuous from the Callovian to the Tithonian. The succession consists of thick clastics with flysch features (Vicente 1981, Vicente et al. 1982). This is the famous Yura Group, which is especially well developed in the Arequipa region (Jenks 1948, Benavides 1962, Vargas 1970, Vicente et al. 1979, Vicente 1981 and 1989; Vicente et al. 1982) and whose southermost outcrops are just across the Chilean border, northeast of Tacna in the Pachía and Palca area (Wilson and García 1962), and less than 50 km north of the Chilean Rio Lluta outcrops. In the Pachía and Palca area, the Upper Jurassic marine succession (Ataspaca Formation) consists of a more than 1000 m thick, fine-grained alternation of graywackes and shales, which in the lower levels have yielded a Callovian fauna of Macrocephalitidae and Reineckeia sp. as well as an Oxfordian fauna with Perisphinctes spp. (Wilson and García 1962). A preliminary sedimentological analyses of this formation implies a typically prograding turbiditic succession (Salinas 1986), with a progressive change from finely laminated marls, typical of distal turbidites of abyssal plains or external margins of turbiditic fans (Td, e), to more sandy facies, similar to lobule deposits from intermediate to middle-fan distributary channels.

In summary, the analysis of the Yura Group in the Arequipa area (16º - 17ºS) (Vicente et al. 1982), the Bathonian-Callovian Puente Formation consists mainly of turbiditic sequences related to the prograding of a submarine fan (León 1981). The paleocurrent and paleoslope directions (Vicente 1981), and the facies changes with proximal successions NW of Arequipa (Yura area) and distal successions in the SE (Chapi area) (Chavez 1982), place the deeper part of the basin towards the SE (Vicente 1981, Vicente et al. 1982, Beaudouin and Vicente 1986) (see Fig. 5). The Pachia-Palca outcrops thus represent the more distal part of the system. Progradation to the SE is fairly evident as the facies, characteristic of middle-fan deposits, are mostly Bathonian at the latitude of Arequipa (Puente Formation) and Oxfordian at the latitude of Tacna (lower member of Ataspaca Formation) (Beaudoin and Vicente 1986). This raises the problem of southward progression in basin evolution and of basin connection with the Chilean Norte Grande, where the end of the Oxfordian (see Fig. 6a) is marked by a regression. According to that hypothesis a zone of greatest subsidence must be located just south of Tacna (18ºS) and then a progressive reduction in depth of the basin should be observed between the latitudes of Arica (18º30'S) and Pisagua (19º35'S) before a "finger" ending in the Kimmerigian. Consequently, a more detailed study of the transitional region located between Pachia-Palca (17º45'S) and Quebrada Chiza (19º15'S) is needed. We expect to find a regression that became progressively younger to the north and transitional features between the evaporitic basin of Tarapacá and the clastic basin of Arequipa.

Figure 5: Dogger extension of the deep turbidite fan of the Arequipa Basin (modified from Beaudoin and Vicente 1986).

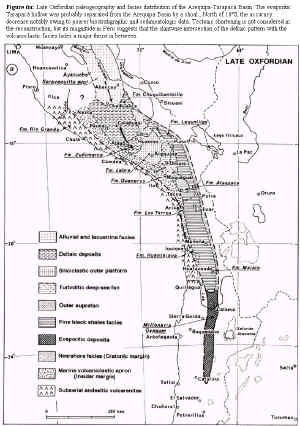

Figure 6a: Late Oxfordian paleogeography and facies distribution of the Arequipa-Tarapacá Basin. The evaporitic Tarapacá hollow was probably separated from the Arequipa Basin by a shoal ; North of 16°S, the accuracy decrease notably owing to poorer biostratigraphic and sedimentologic data. Tectonic shortening is not considered in the reconstruction, but its magnitude in Peru suggests that the slantwise intersection of the deltaic pattern with the volcanoclastic facies hides a major thrust in between.

Figure 6b: Extension of isolated and restricted evaporitic basins in Late Oxfordian.

The scarceness of outcrops and underestimation of Late Cretaceous tectonics in northernmost Chile inhibit interpretation. We know that in southern Peru Andes shortening largely increases so that, just beyond the frontier, the huge northeastward overthrusting of the Arequipa massif appears to be present (Vicente 1989). This is supported by the tectonic window observed in Palpa (Vicente 1989, his figure 9) which shows that the volcanic arc widely overthrusts the retroarc basin and overprints it. Probably that thrust may continue into northernmost Chile.

Likewise, in the North, at latitude of Aplao (16°S) northwest of Arequipa, the noticeable truncation represented on our Figure 6a may be tectonic. Another paleogeographic problem is that in southernmost Peru and in northernmost Chile where the Jurassic volcanic arc is in part submarine so that it becomes hard to differentiate between intra-arc basins and the very insular margin of the retroarc. A good example is the striking cross-section of the Azapa canyon, down stream of Livilcar, where the counterpart of the Junerata Formation of Palpa (=Chocolate Formation of Arequipa) consists of thick pyroclastic turbidites and submarine lava flows. Moreover, these reconstructions must not neglect the extreme fluctuation in time and space of the volcanic activity.

Central Peru (14°- 11°S)

At this latitude there was again an early regression, mainly during the Bajocian. This implies the location of the northern end of the Arequipa basin and the presence to the north of a large continental area, whose weathering contributed to the clastic sedimentation (Fig. 4a). The marine Bajocian outcrops barely reach beyond Huancayo (12º04'S) and belong to the limestones of the Chunumayo Formation which, at the classic locality of southern Huancavelica, yielded a fauna of Sonninia cf. espinazitensis Tornq. typical of the lower Bajocian (Sauzei Zone) (Westermann et al. 1980). Farther north a rapid change occurs to sandy facies (Cercapuquio Formation) (Mégard 1978). Beyond that, Neocomian quartzites (Goyllarisquizga Formation) rest unconformably on the Lower Jurassic.

Towards the south, the regression becomes younger. Thus, 100 km south of Chunumayo, at the latitude of Rio Pumani (13º43'S) of the Paras region, marine facies persist to the Late Bajocian as shown by the assemblage of Leptosphinctes ("Cobbanites") cf. talkeetnanus (Imlay) and Spiroceras orbigny (Baugier & Sauze) collected by Westermann et al. (1980). Sixty kilometers to the southeast, in the Paire region (13º51'S) of the Querobamba geological map, Lower Callovian limestones with Eurycephalites cf. boesei Burck.resemble, according to Guevara, the Gramadal Formation of Arequipa (in Westermann et al. 1980). Considering that this formation is Lower Tithonian at the latitude of Arequipa (Chavez 1982), diachronism is evident. This also shows the need for a detailed biostratigraphic and sedimentologic study of the Yura Group in that intermediate region.

The Chalhuanca area (14º18'S) appears especially suitable, as here the Yura Group has facies comparable to the Arequipa region (Pecho 1981) and biostratigraphic information suggests the presence of marine Callovian, Oxfordian and Tithonian. Furthermore, it may be possible at this latitude to relate, within a mainly longitudinal feeding context, a deep-turbiditic system with fluvio-deltaic contributions coming from the Sarayaquillo continental basin (Fig. 4a). This basin, an extension of the Arequipa marine basin, is the only one that could have provided the quantity of clastics of cratonic origin for the sedimentation of the Yura Group. This relationship, already inferred by Mégard (1978) with regard to the Chunumayo and lower Sarayaquillo deposits, and illustrated by Westermann et al. (1980, fig. 9), is very important for paleogeographic inferences. It implies a longitudinal filling system of the Arequipa basin from the NNW, quite similar to that of the Persian Gulf by the Mesopotamian plain, but under more humid conditions as indicated by the abundance of plant remains in the Yura Group of the Chalhuanca region (Pecho 1981).

The apparent absence of Sarayaquillo facies in the Subandean region farther south is also relevant here, because it would justify a study of paleochannels in the Sarayaquillo Group. This may help to differentiate between lateral and longitudinal provenances and to better assess the importance and meaning of the emergence of central Peru in relation to the Nevadian movements (Vicente 1982).

The main regressional stages: Norte Chico Isthmus and Tarapacá Basin

Based on the previous analysis, we concluded that, as early as Bajocian, the waters of the Andean basin began to progressively withdraw to the north as well as south, starting from the Norte Chico region between 29º and 30º30' S (Transito and Elqui Cordilleras). Since that time, the Andean Basin was divided into two separate subbasins by the Norte Chico Isthmus (Jensen and Vicente 1979) (Fig. 4b): the Aconcagua-Neuquén Basin in the south and the Tarapacá Basin in the north. These two basins became progressively restricted, until complete evaporation (Jensen et al. 1976, Jensen and Vicente 1979). During this last event, the water masses withdrew northward, with the southern basin margin located at (Fig. 2):

- Early Bajocian: Tránsito area (28º52'S);

- Early Callovian: immediately south of Manflas (28º17'S) (Jensen et al. 1976) and Quebrada Paipote (Vega Redonda) (27º08'S);

- Early Oxfordian: slightly south of Quebrada Carrizo (26º06'S) (Jensen et al. 1976);

- Late Oxfordian: immediately south of Quebrada Incahuasi (25º36'S);

- Early Kimmeridgian: close to 25ºS, i. e. on the southern end of Sierra de Varas.

In summary, the northwards regression occurred over ca. 430 km (3º52'S) during 26 Ma, which implies an average rate of regression in the order of 1.6 cm/y. From the comparison of this rate with the 9 cm/y transgression rate, the regression was slower by a factor of 6. However, it is not possible to reduce this regression to simple progressive water evaporation. The Callovian sea was locally transgressive and extended beyond the Bajocian sea north as well as south of Norte Chico (cf. Copiapó and Aconcagua regions). This indicates tectonic control of water displacement.

During this entire regressive phase, clearly opposing facies existed between the eastern (cratonic) and western (insular) margins of the basin. In the western margin is recorded the volcanic activity of the contiguous arc. Thick volcaniclastic continental deposits of western origin systematically overlie the marine successions at the end of the regression. Thus, we have to consider:

- The conglomerates and sandstones with andesitic material characterising the western facies during the Bajocian in the Los Pingos region (Rivano 1975);

- The intercalations of andesitic conglomerates, breccias and tuffs present in the western Bajocian successions of Alto Tránsito (Quebrada Las Pircas and Quebrada Chanchoquin, Hillebrandt 1973) and the Manflas area (Quebrada Cepones and Quebrada Las Maquinas at the headwaters of Quebrada Algarrobal, Hillebrandt 1973; Quebrada Amolanas and Quebrada Calquis (Jensen and Vicente 1976, Jensen 1976);

- The thick flows of porphyritic andesites interbedded in the marine Bajocian of Sierra de Fraga (Davidson et al. 1976);

- The Callovian calcarenites and green sandstones, rich in andesitic clasts, of Quebrada Paipote (Vega Redonda), Quebrada San Andrés (Cisternas and Vicente 1976), Quebrada Asientos western belt (Garcia 1967), that at the latitude of Chañaral Alto include andesitic flows, some with pillow structures (Oviedo 1977);

- Finally, the Callovian-Oxfordian facies of tuffaceous sandstones, conglomerates and andesitic flows, sometimes submarine, which characterize the western slopes of Sierra Exploradora (Davidson and Godoy 1976) and Sierra Candeleros (Naranjo and Covacevich 1979) and also the Cerro Islote, west of Sierra de Varas (Chong 1973) (24º55'S).

In conclusion, the western basin margin, more than 650 km long (24º55' - 30º45'S), is characterised by andesitic material coming from the La Negra active arc (Jensen et al. 1976), to such an extent, that one of the main reasons for the beginning of restricted circulation in the Andean basin appears to be the obstruction and closing of straits by the volcanism.

Although there is little doubt about the withdrawal of the waters towards the north, we also have to consider, in the centre of the Tarapacá evaporitic basin (Caracoles and Cerritos Bayos regions), the brief and ephemeral marine ingression that caused the deposition of the Kimmeridgian carbonate facies above the Millonaria Gypsum. These are the Honda Formation (170 m) of the Caracoles area (Harrington 1961, Montaño 1976), and the lower member (100 m) of the Cerritos Bayos Formation (Baeza 1976), both of which represent an important succession of intraclastic breccias, oolitic and oncolitic calcarenites, and dolomitic micrites with scarce Ostrea sp. and Myoconcha sp. (Montaño 1976). Considering the restricted character of this recurrent marine ingression in the ultimate, most depressed part of the basin, a northern connection appears probable. This would confirm the hypothesis that the Tarapacá basin was raised towards the north, and that it was separated from the Arequipa basin by a barrier at the latitude of Sierra Moreno (Fig. 6a).

South

The regressive basin evolution south of our area of study, i.e. at the latitude of Neuquén, remains to be analysed. In contrast to the area previously analysed with good biostratigraphic controls and a rather well known lithostratigraphy, we have comparatively few precise data for the regression ages and the corresponding facies variations for the Neuquén region, despite the quality and accessibility of its outcrops (see Fig. 3).

Although it was the "birth place" of the South American Mesozoic stratigraphy (Bodenbender 1892, Burckhardt 1903, Jaworski 1915 and 1925, Gerth 1928, Groeber 1929, Weaver 1931, Windhausen 1931, Groeber et al. 1952), the understanding of Neuquén geology has been hindered until de 70's by a lithostratigraphic nomenclature favouring facies continuity over variation. This situation changed subsequently, mainly thanks to the works of Gulisano and collaborators who showed the strong diachronism of many formations and adopted a scheme of depositional sequences (Gulisano 1992). Many sedimentological studies with a sequencestratigraphical approach have been carried out in Neuquén and Mendoza (see Legarreta et al. 1993 and Legarreta and Uliana 1999); still missing are detailed studies on of Late Callovian - Oxfordian ammonite fauna in order to improve the biozonation.

Evaporitic basin of terminal Oxfordian

The southernmost outcrops of the Yeso Principal (Schiller 1912) or Auquilco Formation (Figs. 6a and 6b) (Weaver 1931, Groeber 1946) are slightly north of Zapala in the Sierra de la Vaca Muerta (Groeber et al. 1952, Stipanicic 1966, Marchese 1971, Digregorio 1972) at the northern part of the hill (Fig. 3). The boundary must be placed at the latitude of Mallin del Rubio (38º40'S), where the Auquilco Formation is represented by a thin interval comprising stromatolitic boundstones with thin red intercalations, but may be missing locally due to erosion (Lambert 1956, Chotin 1975, Digregorio and Uliana 1980, Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995a). South of this latitude, the regressive facies excluded evaporites, as shown in the sections in and south of Rio Covun Co (Chotin 1975) at the southern end of Sierra de la Vaca Muerta (Groeber et al. 1952, Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995a, Legarreta and Uliana 1999), and the boreholes of the Plaza Huincul region (Di Gregorio 1965, Digregorio and Uliana 1980). Souh of Zapala the continental facies of the Fortin 1° de Mayo Formation has been considered as equivalent to the Auquilco Formation (Gulisano et al. 1984).

The distance between the northernmost outcrops at Portezuelo del Yesito (31º36'S) of Cordillera de los Sapos in the High Cordillera of San Juan and the southernmost outcrops of Sierra de la Vaca Muerta (38º40'S) in southern Neuquén is 765 km, representing the longitudinal extension of the Aconcagua-Neuquén evaporitic basin (Fig. 4b). Within this context, it should be remembered that the "Yeso Principal" precipitation was the result of a slow basin evolution towards restricted circulation, and ending in oversaturation of the water mass by elimination of the upper body of water and the transition to a one body mass which reached the condition for precipitation and preservation of calcium sulfide. This major salinity crisis resulted for the confinement of the basin under tectonic control which reduced drastically its connection with the open Pacific. As pointed by Legarreta and Uliana (1996), the Auquilco evaporite accumulation followed a geologically sudden (Messinianstyle) desiccation event. However, the very volume of chemically precipitated rocks implies that the seaways were not completely closed and so, according to eustatic fluctuation of sea level, the basin could continue to be fed for a time, as in the Mediterranean case (Rouchy 1982).

All evidence points to a quick filling of the basin. It is therefore probable that these evaporites were generally coeval throughout the basin and that the thickest deposits indicate the deepest parts of the basin (Gulisano 1992, Legarreta and Uliana 1999). This interpretation differs from previous ones (Groeber et al. 1952, Digregorio 1965 and 1972, Stipanicic 1966), which accepted different ages for the Auquilco Formation and held that the thickest deposits were the marginal facies of the basin. Regarding the age of this precipitation, the youngest faunas collected from the pre-gypsiferous levels of the La Manga Formation at Arroyo Santa Elena (Davidson and Vicente 1973), Rio Atuel (Stipanicic 1951), Vega de la Veranada (Stipanicic 1966, Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995b) and Sierra de Reyes (Groeber et al. 1952, Stipanicic et al. 1975) indicate the ? Cordatum and Plicatilis Zones. The age of the gypsum is therefore Late Oxfordian to Early Kimmeridgian.

With regard to the boundaries of the evaporitic basin (Fig. 3):

- The eastern margin, at the latitude of Neuquén, is well established by several boreholes (Digregorio 1972), which locate the margin close to Añelo (68º 34' S; see Gulisano 1992; Legarrreta and Uliana 1999). From there, the coast line continued NNW and passed close to the eastern slope of Sierra de Reyes (69º40'S). After a slight westward displacement at the latitude of Sierra Azul and Bardas Blancas (69º48'S) where the gypsum is missing (Stipanicic 1966, Gulisano 1992) at Tronquimalal or Potimalal (69º35'S), the margin followed northward to the latitude of Río Atuel, just east of Arroyo La Manga (69º35'W); then east of Laguna del Diamante (69º39'W) and, finally to the Puente del Inca region (69º52'W).

- The western margin, beginning at Mallín de los Caballos, continues NNW, passing Cuchilla Cura and the NW flank of the Vaca Muerta anticline where the gypsum is clearly beveled (Lambert 1956, Chotin 1975); before following approximately the S-N course of Rio Agrio where, at the latitudes of Campana Mahuida (Chotin 1975) and Loncopué (Groeber et al. 1952, see Gulisano 1992), mixed facies with thin gypsum and dolomitic limestones indicate proximity of the coast. To the west, the area of Lonquimay was undoubtedly elevated at that time, because the upper Bathonian-(lower Callovian) marls are overlain by only 50 m of volcanic sandstones with Cidaris sp. and superposed by thick Upper Jurassic andesitic flows (Burckhardt 1900b, Chotin 1975, Suárez et al. 1988, Riccardi and Westermann 1991, De La Cruz and Suárez 1997).

Farther north, the coast line approximately followed the meridian of Andacollo (70º40'W). The dolomitic-calcareous mixed facies with stromatolitic levels and intraclastic breccias (Dellapé et al. 1979) of Rahueco, Chacay Melehue and Los Menucos pass gradually into the continental facies of Rincón de Piedra (Zöllner and Amos 1973) on the southern end of Cordillera del Viento, leaving little doubts about the littoral character of these deposits. Curiously, these so called "Chacay Melehue facies" (Stipanicic 1966) were interpreted to represent the deepest basin deposits (Groeber et al. 1952, Stipanicic 1966); only Marchese (1971), Davidson and Vicente (1973) and Gulisano et al. (1984) considered that these deposits may be indicative of the evaporitic basin's western margin.

Further north, at the 35ºS latitude, the coastline was just west of Vergara Villagra, i.e. on the 70º30'W meridian, as indicated by the rapid westward thinning of the gypsum in the western limb of the Río Vergara anticline (Davidson 1971). It is difficult to farther follow the margin due to the Major Andean Overthrust (Vicente 1970, 1972, 1993 and 1998) which systematically overprinted the western basin margin. Since precise magnitude of that overhrusting is unknown, it is difficult to assess the exact position of the western coastline between 35º and 31º38'S, but 10- 15 km west of the overthrust front seems reasonable. The proof of a continuous oceanic communication at the Atuel latitude during this evaporitic phase, on the other hand, would require a more detailed study of the underlying deposits and of coeval evaporitic successions, in order to record any marine ingressions between the evaporitic cycles. But the early pre-Late Bajocian regression (Covacevich and Piracés 1976) that characterizes the Coastal Cordillera at this latitude, renders this alternative improbable.

Early Oxfordian pre-evaporitic basin

With regard to the previous boundaries of the basin, the pre-evaporitic deposits represented by the La Manga Formation and its equivalents occupied a slightly larger area (Fig. 3; cf. Gulisano 1992). This is especially evident in the southern region, where the subsurface distribution of the Barda Negra Formation (Digregorio 1965) allows us to locate the Early Oxfordian coastline south of Zapala and immediately NW of Plaza Huincul (Digregorio 1972), barely surpassing the 39º S latitude. These brown and green marls and shales, interbedded with thin beds of green sandstones, dated Oxfordian by the presence of Peltoceratoides sp. (Digregorio 1972), represent the coastal facies of La Manga Formation (Stipanicic 1966). As on the eastern part of the Neuquén basin (east of Añelo) they gradually pass into the medium- to coarse-grained sandstones of the continental facies of the Sierras Blancas Formation (Digregorio 1965). This "Barda Negra facies" (Stipanicic 1966), restricted to the basin's SSE margin, seems to be a lagoonal paleoenvironment that developed behind the carbonatic barrier. This barrier is represented by the "Vaca Muerta facies" (Stipanicic 1966) with its coralline calcarenites and lumachelles with "Gryphaea cf. calceola Quenst.", along the eastern basin margin, from Sierra de Vaca Muerta to beyond Malargue via Sierra Azul and Bardas Blancas (Stipanicic 1966).

In summary, the Early Oxfordian events, at the southern boundary of the evaporitic basin in the Zapala meridian (70ºW), indicate a northwards regression of about 30 km, whilst on the eastern margin, at Bardas Blancas latitude (36ºS), the regression was 15 km. On the other hand, it is difficult to asses the coastline variations west of Codihue at the latitude of Cerro Media Luna where (see Chotin 1975) there are coralline facies resembling those at the southern end of Sierra Vaca Muerta. The variations of this margin were probably smaller than those of the cratonic margin according to basic transverse asymmetry of the basin and the active tectonism of the island margin.

Callovian basin

During the Callovian, the southern end of the Neuquén Basin was located farther south at about 39º15'S (Fig. 3). Sedimentological analyses performed by different authors (Rosenfeld 1978, Zavala 1993. Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995a) of the Lajas and Challacó Formations (Bathonian-Callovian) in Sierra de Chacai Co has shown that this is a typically paralic - with pronounced deltaic features - to braided fluvial succession. This marked the quick transition from a littoral marine environment, at the base, to the pure continental facies of an alluvial plain (Lotena Formation), at the top. The mostly high-energy, sandy sedimentation indicates a quick regression resulting from an important uplift (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1979). Detailed measurements of the oblique cross-bedding indicate a generally eastward and northward paleocurrent regime in the northern Sierra. This, together with the more frequent marine influx from the NE and the existence of marine intercalations with Middle Callovian ammonites (Rehmannia patagoniensis, cf. Riccardi and Westermann 1991) at the anticline of Picun Leufu, suggests a NNW-SSE orientation of the coastline at this latitude. These data emphasize the importance of the western contributions compared with those generally mentioned (Groeber et al. 1952) from the southern North-Patagonian Massif. The continental area with major weathering was unquestionably located to the west, and the Chacai Co facies marks the western basin margin, close to its southern end (Fig. 3).

Farther south, in the Piedra Pintada region (40º15'S), the regression was even older and probably Bajocian (Fig. 3). This classic Lower Jurassic marine succession of southernmost Neuquén, mainly Pliensbachian in age (Damborenea et al. 1975), passes continuously upward into a thick succession of pyroclastic volcano-sedimentary, acid flows, sandstones and conglomerates (Galli 1969) of probably Late Toarcian - Early Bajocian age. This ended the regional marine sediments, which Digregorio (1972) includes in the Lajas Formation. We also point to the existing strong analogies between this volcano-sedimentary succession and that of extra- Andean Chubut (Musacchio and Riccardi 1971) in Sierra de Agnia. This analogy conduced Riccardi to consider the levels with Piedra Pintada fossiles as biofacies of the same age, i.e. Pleinsbachian. Here the marine, tuffaceous Lower Jurassic (Osta Arena Formation) passes upwards into a thick volcanic succession (Lonco Trapial Group of Lesta and Ferello 1972). This suggests a late Toarcian age for the regression at this latitude (43º45'S). Besides, to date no paleontological evidences for Aalenian-Bajocian has been found in either region (Riccardi, written com. 2003).

With regard to the distribution of Callovian facies, there exists, south of Zapala, a neritic domain associated with a deltaic system (Digregorio 1972). Towards the north it quickly passes into the Bathonian-Callovian shaly facies of the Chacay Melehue Formation (Cangini, 1968; Digregorio 1972). These relatively deep facies occur in an essentially continuous belt, from Paso Pino Solo (38º35'S) of Lonquimay to Portezuelo Flores (31º45'S) of Río Pachon and mark the axis of the Bathonian - Callovian basin. To the east, on the cratonic margin, a wide belt (Lotena Formation) of shelf sandy limestones and calcareous sandstones (Groeber et al. 1952) developed. East- and northeast-ward, the Chacay Melehue Formation of the Loncopué region (38º05'S) with tuffaceous intercalations, fluxoturbidites and levels with imbricated olistoliths (Rosenfeld and Volkheimer 1980), and the Chacay Melehue region (37º15'S) with tuffs, spilitic lavas with pillow structures (Zöllner and Amos 1973) and turbidites with deformation structures due to slumping (Gulisano and Gutiérrez Pleimling 1995a), indicate the proximity of an active volcanic arc at the western basin margin. In Lonquimay, Upper Bathonian (-Lower Callovian) facies are coastal turbidites with abundant volcanics. The western coastline was west of Loncopué, Chacay Melehue and Nacientes del Teno (35º10'S), where the (Bathonian-) Callovian consists of green volcanic arenites with many slump levels indicating an easterly slope (Davidson 1971; Davidson and Vicente 1973), and eastwards (Nacientes de Santa Elena) interfingers with shaly facies.

The eastern coastline of the southern region followed a SW-NE direction passing more than 20 km southeast of Plaza Huincul (Groeber et al. 1952). This is evident in the Loma Negra borehole, just west of that locality, which shows facies of sandstones and argilites of deltaic origin, whilst to the southeast the Challacó borehole shows typically continental red sandstones and conglomerates (Digregorio 1972). East of Añelo, before reaching the 68ºW meridian, the coastline changed to a NW direction, bypassing the Rio Negro border of the Catriel region, because the Punta Rosada borehole (68ºW, 38ºS) also showed typically continental facies (Digregorio 1972). After Buta Ranquil, the eastern coastline continued in a N-S direction near the eastern slopes of Sierra de Reyes and Sierra Azul, before passing Bardas Blancas and immediately east of Puchenque and Arroyo La Manga, finally connecting with the Puente del Inca coastline (Fig. 3).

Main regressional stages in the southern end of the Neuquén Basin

Summing up, a progressive northwards regression started in extra-Andean Chubut, with the following main stages at centralnorthern Chubut and the southern end of the Neuquén Basin:

- Late Pliensbachian-Early Toarcian: Sierra de Agnia region (43º45'S);

- Late Toarcian-Early Bajocian: Piedra Pintada region (40º15' S) - southern Sierra de Chacaico (39º25'S);

- Middle Callovian-Early Oxfordian: Immediately south of Zapala, at 39º - 39º10'S;

- Middle Oxfordian: Mallin del Rubio latitude (38º40'S) - Sierra de la Vaca Muerta. This implies a distance of over 650 km in 31 My, i. e. the average rate of regression was of the order of 1.8 cm/y, 5 times lower than for the transgression. We conclude that the cause of this slow, northward regression was epirogenic rather than orogenic. Furthermore, the rate of the regression diminished from the Callovian onwards.

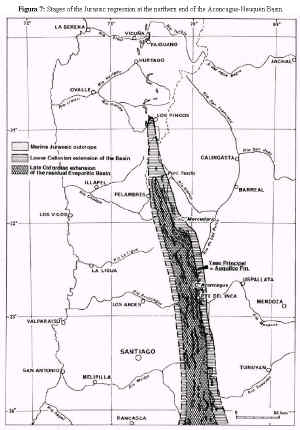

Main regressional stages in the northern end of the Aconcagua-Neuquén Basin

It remains to analyze the regressional features in the Aconcagua-Neuquen Basin's northern end, i. e. north of our study area, and on the Norte Chico Isthmus uplift. Between latitudes 29º and 30º30'S, the regression began in the Early Bajocian. Rivano (1975 and 1980), Hillebrandt (2000) showed for the Los Pingos region of Cordillera Ovalle, that in the Late Bajocian the northern end of the Neuquen Basin was located immediately north of Los Pingos at 30º52'S. At this latitude the facies are typically littoral with conglomerates, sandstones and red pelites with intertidal sedimentary structures. This indicates the end of the gulf, here reduced to no more than 3-4 km in width, and surrounding an axis of euxinic infra-littoral shales and calcilutites (Rivano 1975). The petrography of the terrigenous deposits differs between the western margin, with andesitic material, and the eastern margin, with pre-Andean material of rhyolites and gondwanian granitoids. In the Late Oxfordian, the Yeso Principal evaporitic basin ended just north of Portezuelo Yesito, by 31º35'S (see Fig. 7). This implies a southwards regression of about 120 km in 18 My, i. e. an average speed of only 0.6 cm/y, 3 times slower than in the southern region (1.8 cm/y).

Figure 7: Stages of the Jurassic regression at the northern end of the Aconcagua-Neuquén Basin.

MAIN FEATURES OF ANDEAN JURASSIC PALEOGEOGRAPHY

Permanence of paleogeographic and structural features

We conclude that there were close coincidence and symmetry between the general transgressive and regressive movements at the latitudes of the Andean Basin. This is evident from the observation that the areas of late transgression are the same as those with early regression, whilst those with early transgression are the same with late regression. There appears there were areas with permanent uplift trend along the basin (Norte Chico Isthmus and extra-Andean south Neuquen-Chubut) and others with subsidence trend (Tarapacá Basin and Aconcagua-Neuquén Basin).

This permanent tectonism is all the more surprising as it also persisted during the Tithonian-Early Cretaceous cycle (Jensen and Vicente 1979). The biostratigraphic control for this later cycle is more concise, confirming the similarities in the main features of the trangressions and regressions. For example, the transgression occured in the Tithonian at the latitude of Quebrada Asientos (26º30'S) (Harrington 1960, García 1967, Pérez 1978), and in the Valanginian at the latitude of Copiapó (28ºS) (Tavera, 1956). Symmetrically, it occured in the early Tithonian at the upper course of Río Mendoza (33ºS) where in Quebrada Vargas we collected (det. Covacevich, 1973) a fauna with Virgatosphinctes cf. V. andesensis (Douvillé) and aff. "V." erinoides (Burckhardt), Aulacosphinctes sp. and Paraboliceratoides sp. (see also Lo Forte 1996), whereas at the latitude of Alto Limari (31ºS) the age is late Berriasian (Mpodozis and Rivano 1976) on the basis of Spiticeras sp. and Cuyaniceras sp. In our study area, the Early Cretaceous basin is clearly narrowing towards the north. This is especially evident on the western slope of Cordón de la Ramada, where the E and NE thinning of the Lower Cretaceous calcareous level and the thickening of a facies of red sandstones indicate an important NW inflexion of the coastline. In summary, we found for this time in Norte Chico the same positive tendency as for the Jurassic. This suggests that a type of analysis similar to the one here discussed for the marine Jurassic could be performed on the Tithonian-Lower Cretaceous cycle (Andico cycle).

That permanence of paleogeographic and structural features along the Central Andes, with reiteration during the Tithonian-Early Cretaceous cycle of the same patterns of transgressions-regressions (see Legarreta and Uliana 1991), leaves no doubt about the basic regional tectonic control of that retroarc basin. Its behavior is closely subordinate to the tectonic and magmatic activity of the volcanic arc which was boundering it on the West. Insofar as we have shown the importance and remarkable continuity of that volcanic arc during the course of Jurassic, it is no longer possible to reconstruct the basin on the basis of data coming only from the cratonic margin even if a wealth of petroleum data are available for the Neuquén embayment. It will be necessary to pay much more attention to the insular margin of the basin if we don't want to lose sight that it was basically a retroarc basin on continental crust and became an integral part of an intrinsically active margin which behavior is dictated by the convergence and so by the variations of the subduction process.

Dynamic of water masses: regional tectonics versus global eustasy model

Considering the Andean Basin during the Jurassic in a dynamic context, the progressive connection of the Tarapacá and Aconcagua-Neuquén Basins and their subsequent separation until confinement become evident, and the main movements of the water masses become clear. In particular, we try to explain how the regression in the distal parts may influence the cratonic margins of the central parts of the basins, with transgressive facies caused by displacement of the water masses, so that is unnecessary to infer important tectonic movements on the cratonic margin. Examples can be found in the Bajocian at the latitude of Copiapó (Jensen et al. 1976) and the Callovian in the Mercedario region (see also Alvarez 1996 a, b, c, 1997) and the southeastern part of the Neuquén gulf, i. e. the Lotena Formation and its associated sedimentary subcycle (Dellapé et al. 1979). All this happened even without having to consider any marine ingressions coming from the Pacific through a strait in the arc or any global sea-level rise.

In that dynamic framework where the shifting of water masses appears at first sight indisputably tectonic, it is clear that the recording of assumed global eustatic cycles remains very subordinate and difficult to identify. This is especially so because the arc magmatic activity seems to have also contributed considerably in variations of sediment supply to the basin and later interfered with the generation of a clear signal of eustatic sea-level change. If we consider the relative sea-level curve from latest Triassic to Jurassic proposed by Hallam (1991, his figure 2) for the Andean Basin and compare it with that established from Europe by Haq et al. (1987) or Hallam (1988), obvious dissimilarities become patent. The main is the Late Jurasic Andean regressive phase with wide spread Upper Oxfordian gypsum overlain by mainly continental Kimmeridgian a time when in Europe were relatively very high sea-levels. This major regression in the Andean Basin is recognized from Neuquén to Northern Chile, it affected an area of hundred of thousands of square kilometers and so testifies a major episode of uplift on a regional scale. According to Hallam et al. (1986) it expresses a sudden eastward extension of the volcanic arc. Initially viewed as a simple diastrophic phase (Stipanicic and Rodrigo 1970), it is now considered as a genuine orogeny known as the Araucanian Event. Its compressive tectonic effects have been for a long time underestimated (Vicente 1984). It is clear now that it produced a widespread inversion in southern Neuquen (Ploszkiewicz et al. 1984, Vergani et al. 1995). The famous unconformity at Cerro Lotena (Suero 1951) is a classical example of that inter-Malmic episode on the Dorsal de Huincul. Synsedimentary compressive structures are also present north of Zapala in Sierra de la Vaca Muerta (Zavala 2002) and considered responsible for the northward migration of the Lajas Formation depocenter. An Intracallovian unconformity shows that partial inversion even began in the Late Bajocian (Covunco anticline).

A symmetrical situation is found at the latitude of Norte Chico, in the area of Rivadavia of the Elqui Cordillera. There the Upper Jurassic continental and volcanogenic Algarrobal Formation seals unconformably compresive structures affecting the marine Jurassic (Dedios 1967, Mpodozis and Cornejo 1988) as attested by its restoration to horizontal.

Evidence of a strong uplift of the Arc is proved by the thickness and coarseness of the fanglomerates of the Rio Damas Formation of Central Chile High Cordillera, a typical depositional system of alluvial fans developed during the Kimmeridgian and interpreted as the proximal facies of a foredeep against an uplifted volcanic source area (Charrier 1981), which graded eastward to the distal red beds of the Tordillo Formation in Argentina.

Regarding the Coast Range of the Norte Chico and Central Chile, it is customary to speak of a "Malm hiatus" (Thomas 1958). It comes out by a significant erosion, a deep rubefaction and a conspicuous unconformity of the Neocomian beds. Locally the erosion is such that these deposits lie direct on schistose Triassic of the forearc (Moscoso et al. 1982, Rivano and Sepúlveda 1991). The extensive Upper Jurassic plutonism which intruded this range (Rivano et al. 1985, Gana and Tosdal 1996) and the syntectonic metamorphism and shear zones associated with their emplacement (Godoy and Loske 1988, Irwin et al. 1988) must be added in order to appreciate the entire Araucanian Orogeny in the midst of the Arc.

The second extensive lowstand pointed out by Hallam's eustatic curve deals with the Bathonian. For a long time it was believed in the absence of Bathonian in South America and supposed a general regression for that time (Harrington 1962). But this age was underestimated for biostratigraphic reasons linked to the endemic character of Andean ammonites and the lack of Cardioceratidae and scarcity of Parkinsonidae. Recent studies of continuous stratigraphic sections going from Upper Bajocian to Callovian in shaly facies as in the Domeyko Cordillera or in the western Neuquén have allowed to establish a zonation on the ground of Andean Eury -cephalitinae and to propose its correlation with the standard zones (Chong et al. 1978, Riccardi 1985, Riccardi et al. 1988, Riccardi and Westermann 1991). These sections, as in our study area in the Río Los Patos and Alma Negra Types (Fig. 4 of Vicente 2005), do not show any significant change in their bathymetry during this stage. However, they were deposited in water too deep to record minor fluctuation of the sea level. In southern Peru, the Bathonian is even the stage of greatest subsidence in the Arequipa Basin (Vicente 1989). Ardill et al. (1998) already have suggested that the fall was of low magnitude and notably less than the one argued by Hallam (1991).

Regarding Hallam's important Andean transgressive pulses in the Hettangian, early and late Sinemurian, late Pliensbachian - early Toarcian, early Bajocian and early Callovian and his attempts to correlate those with episodes of sea-level rises elsewhere in the World, these results are too strongly linked to the hazards of sampling and the lack of real and systematic 3rd-order sequences analysis with paleobathymetric interpretations to be considered unquestionable. Without taking part in the controversy raised by Miall (1992 and 1994) about the Exxon global cycle chart (Haq et al. 1987) concerning its illusory precision "because it is greater than that of the best available chronostratigraphic techniques" and the danger of circular reasoning in using it as a template for stratigraphic correlation since "almost all stratigraphic events can be found to correlate successfully with this chart when allowance is made for error", it is clear that in the Andean context an insufficiant attention has been paid to the preponderant part played by regional tectonics on the dynamic of water masses. Concerning the observed pattern of transgression, it expresses more the post-rift flooding of a subsiding retroarc basin than real transgressive pulses.

Mutti et al. (1994) emphasized the nature of the Andean retroarc basin as a typical barred basin with limited connection to the open ocean, whose depositional sequences were strongly controlled by the filter or amplifier effect and display produced by the relative elevation, in space and time, of the sea floor in the seaways and straits connecting it with the Pacific Ocean. In particular, their conceptual diagrams show how sea level fluctuations occurring below the shoal separating the forearc from the retroarc will not be recorded in the basin or, on the contrary, filtered (only high stand recorded) when fluctuations contain it. That explains the distinctive characteristics observed in the sequence-stratigraphic setting of the Jurassic Neuquén Basin with respect to those described in sequence-stratigraphic models currently in use. Though their model considers mainly eustatic variations, this does not preclude the tectonic mobility of these straits. Our analysis suggests that, most likely, the main sea floor fluctuations in the seaways across the arc were tectonic and magmatic.

Numerous authors performing sequencestratigraphical analysis have nevertheless tried to interpret sequence boundaries in the Central Andes in term of relative sealevel fluctuation and to correlate them with the global eustatic chart. This was often attempted with an amazing precision as in the case of the Neuquén basin (Legarreta et al. 1993, Legarreta and Uliana 1996) and the Domeyko basin (Ardill et al. 1998). It must be pointed out that these attempts were based exclusively on longitudinal correlations without care of the along-strike dynamism specific to these basins. Moreover, as concerns the particular case of the Domeyko basin, it is clear from our point of view that these authors (Ardill et al. 1998) have greatly underestimated the real bathymetry of the basin and interpreted as erosional shoreface deposits many typical turbiditic facies which in no case indicate a basinward shift in facies and can not be imputed to a forced regression lowstand. Just as, according to Jaillard et al. (1990), they refer to a marked Upper Oxfordian unconformity in southern Peru we never learnt about.

Weak endemism in biogeography

It is interesting to compare the scheme of longitudinal evolution of the Andean Basin with the ammonite paleobiogeographic data. These are available at the generic level from the reviews of faunal relationships (Hillebrandt 1970 and 1972, Riccardi 1991a, Hillebrandt et al. 1992, Westermann 2000) for the Lower Jurassic (Hillebrandt 1979, 2000 and 2002), the Middle Jurassic (Westermann and Riccardi 1976, 1984 and 1985; Westermann 1980, 1981 and 1996; Gröschke and Hillebrandt 1993, Hillebrandt and Gröschke 1995) and Oxfordian (Stipanicic et al. 1975, Melendez et al. 1989, Gygi and Hillebrandt 1991).

The rapid transgression with remarkable continuity of the Andean Basin and the important exchanges through the straits (Ibague, Olmos, Taltal and Curepto) may be related to the character of the faunas: In the "South American Lias, from north to south and from east to west, there are not found many compositional differences in the ammonite faunas of beds of the same age" (Hillebrandt 1979). The Andean Lower Jurassic ammonite faunas comprise a uniform province with connections to Tethyan faunas -through eastern Tethys first and the Hispanic Corridor later-during Hettangian - Early Toarcian times and with North America in the Early Pliensbachian - Toarcian (Hillebrandt 1979, 2002, Riccardi 1991a). Although diversity is relatively low and Phylloceratinae and Lytoceratinae occur only sporadically, probably as a result of restrictions in faunal exchange through the Andean volcanic arc. East Pacific faunal differentiation reached a maximum in the Pliensbachian and was less pronounced during the Toarcian, when most genera and some species were pandemic.

During the Middle Jurassic (Westermann and Riccardi 1976 and 1985, Riccardi 1991b, Hillebrandt et al. 1992, Westermann 2000) open faunal connections with the western Tethys existed at the Toarcian- Aalenian boundary, the end of the Early and the beginning of the Late Bajocian, and in the late Early-Middle Callovian, whilst endemic and east-Pacific genera present during the Late Bajocian - early Early Callovian indicate intermittent or restricted faunal exchanges. Late Bathonian-Callovian Andean genera were also present in New Zealand (Westermann et al. 2002) indicating an overlap of east-Tethys and east-Pacific faunas. Diversity shows a maximum in the Early Bajocian and a minimum in the (Early) Callovian. This trend is correlated with an increasing number, first of exclusively endemic, and later of East Pacific and Pacific genera. In the Oxfordian, the Andean fauna bear close resemblances to those of Europa and the western Tethys. The almost total absence of the "Leiostraca", Phylloceratidae and Lytoceratidae, could also be due to isolation from oceanic influences (cf. Hillebrandt et al. 1992).

Summing up, it is evident that the faunal connections recorded until the middle Oxfordian (Plicatilis Zone) do not reflect distinctly at the ammonitide generic level the regression beginning in the Bajocian and resulting in the subdivision of the Andean Basin in two independent sub-basins. However, Westermann and Riccardi (1985, fig. 5) noted a decrease in the number of Tethyan and Cosmopolitan genera and the occuence of strict endemics in the Aconcagua-Neuquén Basin compared with the Tarapacá Basin and so argued for a distinction between two subprovinces (see also Westermann 1996). A similar conclusion is reached by Damborenea (2002) concerning Bivalves since she notes "further north (northern Chile and Peru) there are very few (if any) Austral elements and the Tethyan influence is more evident". So, save the handicap of Tethyan elements to migrate very south, this compels us to conclude that the straits through the arc had an active role in the exchange during that time. It seems therefore that the faunas migrated freely along the south-eastern Pacific margin and periodically penetrated the Tarapacá and Aconcagua- Neuquén basins during the regressive phase. In this regard, rather than study the regressive features on the cratonic margin, the way to study how these straits worked is through the variations in salinity in the basin and, especially, in the evaporitic successions.

Thus, there are reasons for assuming that the so called Bathonian "Yeso Inferior" (Tabanos Formation) (Stipanicic 1966) widely distributed in the Jurassic successions of W and NW Neuquen (Dellapé and Pando 1976 in Dellapé et al. 1979), from Rio Atuel (Gerth 1925, Groeber et al. 1952) to Sierra Vaca Muerta (Groeber 1921, Lambert 1956, Stiapanicic 1951), attests to a first salinity crisis in the Neuquen Basin. This was probably caused by a brief interruption of the strait communication with the Pacific.

Conditions were similar in the Tarapacá Basin, where the carbonate deposits of Honda Formation (Harrington 1961) overlying the Millonaria Gypsum in the Caracoles (Montaño 1976) and Cerritos Bayos (Baeza 1976) region, point to a brief post-evaporitic marine ingression. However, it is difficult in this case to decide between an eventual origin through the arc and a more probable south-Peruvian marine ingression. A detailed study of the evaporitic successions may enable to show the presence of short marine entrances during the basin's drying process.

There was a lasting Pacific influence during practically the whole history of the Andean Basin. If some differences could be shown between the Tarapacá and Aconcagua-Neuquén basins for the Callovian-Oxfordian, these probably occurred at the specific level.

Finally, these good biogeographic evidences for sporadic exchange between the eastern Pacific and western Tethys since the Plienbachian bears out the idea of a Hispanic Corridor (Cratonic proto-Atlantic) which, as a shallow epicontinental seaway, allowed fauna migrations (Smith 1983, Hallam 1983 and 1994, Jansa 1991, Damborenea 2000). This leads to look with some reserve the paleogeographic map of the western Tethys presented and discussed by Bassoullet et al. (1993) for the Middle Toarcian which denies any connection. So, this favors the Jaillard et al. (1990)'s Tethyan model.

Critics of the Dorsal del Chubut

Considering the paleogeographic connections inferred for the late Early Jurassic between Neuquén and extra- Andean Chubut (Lesta and Ferello 1972) and the notion of a single Neuquén- Chubut basin in the Late Pliensbachian - Toarcian (Fig. 13b of Vicente 2005), we have to discuss the Dorsal de Chubut concept, introduced by Aubouin and Borrello (1970) and Chotin (1975).

We submit that the notion of a Precambrian basement high (dorsal) with NNW direction, which connected the north Patagonian Massif with basement of the coastal region of Concepción at the latitude of Bariloche, and separated the Andean Basin from the Magallanes Basin (relé sur-argentino or of Bariloche, in Aubouin and Borrello 1970), suffered from a significant lack of information on the Patagonian Cordillera. Its definition as "high zone where (from the end of Triassic onwards) nothing will be sedimented" ... and furthermore, "not affected by volcanism" and on which should end ... "as a finger glove" the Andean Basin (Chotin 1975, p. 75) is barely compatible with current knowledge.

It suffices to recall the continuity and importance of the Jurassic volcanics along the North Patagonian Cordillera and the indisputable southwards prolongation (at least until 47º S) of the calcalkaline arc. This is supported by the mentioned record by Cuerda et al. (1981) of a Lower Jurassic bivalve fauna in the volcano-sedimentary Aluminé Formation (39º20'S regarded as Pliensbachian by Pérez and Reyes (1977), and the dating of the Piltriquitrón Formation (42ºS) by Lizuain (1980), also as Lower Jurassic by a bivalve fauna. The Aluminé Formation is securely correlated with the Millaqueo Formation of the Huemul Group (Gonzalez Bonorino 1974) of the Nahuel Huapi southern region and the Montes de Oca Formation (Gonzalez Diaz 1979) for the northern region, as well as with the El Fuerte Formation (Greco 1975) of the Monte Tronador region (41º15'S) and the outcrops of Cordón de Leleque (42º30'S) - not to mention the Futaleufú Group of Thiele et al. (1979) for the Chilean sector (43º19'S) and the Jurassic volcanics described by Haller (1979) for the Argentinean sector west of Trevelín. Considering also the continuity of the volcanic arc between 43º and 47ºS shown by Haller and Lapido (1980), whose activity began in the late early Jurassic (171 ± 5 Ma, K-Ar) and continued until the late Jurassic, it is plain to see that few doubts remain about the continuation between 39º and 47ºS of this essential feature of Andean paleogeography (Lizuain 1999, Giacosa and Márquez 1999).

Added to this continuity of island volcanism is the Cretaceous plutonism of the North Patagonian batholith as shown by the absolute ages (Toubes and Spikerman 1973, Stipanicic and Linares 1975, Halpern and Fuenzalida 1978, Gonzalez Diaz and Valvano 1979, Gonzalez Diaz 1982, Rapela et al. 1987, Latorre 2001). In summary, this was a true magmatic dorsal that was continuous to the south. The volcanic nature seems to have evolved gradually to more acidic types. In fact this development may express partly the paleogeographic obliquity of the arc. If the zonation observed at the Norte Chico latitude (Vicente 1976) is compared, the acidic belt typifies the arc westernmost part, as the andesitic belt occurs mostly to the east in extra-Andean Chubut.

In summary, it is clear that during the Jurassic a Precambrian dorsal did not exist which, beginning in Bariloche, separated the Andean system from the Magallanes system. Rather there is continuous gradual change from one system to the other as already pointed out (Vicente 1970). It seems therefore advisable to abandon the supposition of an Andean system that was unrelated to the Magallanes system (Aubouin and Borrello 1970), and instead support the more fruitful hypothesis of a Patagonian transition favouring the progressive appearance of alpine tectonic characteristics. Further work remains to be done to precisely establish where and how are represented the forms and latitudes of features such as flyschs, ophiolites, nappes and regional metamorphism.

CONCLUDING REMARKS