Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Darwiniana, nueva serie

versión impresa ISSN 0011-6793

Darwiniana vol.49 no.1 San Isidro ene./jun. 2011

ESTRUCTURA Y DESARROLLO

Pollen morphology of Cyclanthera and Sicyos species (Cucurbitaceae, Sicyoeae)

Luis F. P. Lima1 & Silvia T. S. Miotto2

1 Centro de Ciências Rurais, Universidade da Região da Campanha, Av. Tupy Silveira, 2099, Bagé, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil; luisfernandopaivalima@gmail.com (autor corresponsal).

2 Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9500, Bloco IV, 91.501-970, sala 214, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

Abstract

Pollen morphology of eight species of Cyclanthera and three species of Sicyos was studied using light and scanning electron microscopy. Pollen grains of Cyclanthera have a mean polar diameter of 51.40 µm, and an equatorial mean diameter of 49.10 µm, a prolate spheroidal shape (P/E = 1.11), 4-7 zonocolporate, with circular endoapertures, and punctitegilate exine. Pollen grains of Sicyos have a mean polar diameter of 50.60 µm and a mean equatorial diameter of 61.30 µm, an oblate spheroidal shape (P/E = 0.88), 8-12 colpate, supra and microreticulate echinate exine. Differences among the genera and species are discussed.

Keywords. Cucurbitaceae; Pollen; Sicyoeae.

Resumen

Se estudió la morfología polínica de ocho especies de Cyclanthera y tres especies de Sicyos con microscopia óptica y electrónica de barrido. Los granos de polen de Cyclanthera presentan un diámetro polar medio de 51,40 µm y un diámetro ecuatorial medio de 49,10 µm, con formato prolato esferoidal (P/E = 1,11), 4-7 zonacolporado con endoabertura circular y exina punctitegilada. Los granos de Sicyos poseen el diámetro polar medio de 50,60 µm y un diámetro ecuatorial medio de 61,30 µm, formato oblato esferoidal (P/E = 0,88), 8-12 colpados, y la exina supra y microreticulada equinada. Se discuten las diferencias entre los géneros y las especies.

Palabras clave. Cucurbitaceae; Polen; Sicyoeae.

INTRODUCTION

In tropical America, the family Cucurbitaceae is represented by 53 genera and approximately 325 species (Nee, 2004). Most representatives of the tribe Sicyoeae occur in the Neotropical region, and with the highest diversity in the two genera Cyclanthera Schrad. and Sicyos L. (Jeffrey, 2005). Cyclanthera comprises 31 species distributed between Mexico and Argentina, and Sicyos about 60 species distributed in the Americas, Hawaiian islands, Galapagos and one or a few species in Australasia (Jeffrey, 2005; Sebastian et al., 2010).

The division of Sicyoeae in two subtribes is based on pollen morphology, among other morphological characteristics. Cyclantherinae is characterized by pollen grains 4-8 colporate and punctitegilate (Marticorena, 1963; Jeffrey, 1990; Shridhar & Singh, 1990; Stafford & Sutton, 1994; Khunwasi, 1998), and Sicyinae by pollen grains 7-15 colpate and echinate (Marticorena, 1963; Shridhar & Singh, 1990; Khunwasi 1998).

Based on information related to the number, position, and type of aperture in pollen grains, described in the literature and from personal observations, Shridhar & Singh (1990) classified Cucurbitaceae pollen grains in nine main groups or morphotypes, where grains of the species in the subtribe Sicyoeae are multicolpate and circular, and in the subtribe Cyclantherinae are multicolporate.

The first comprehensive study of the pollen morphology from species of Sicyoeae is that of Marticorena (1963), who described the morphology of pollen grains of 30 species using the NPC system. After that, some studies described the pollen morphology of selected species in Cyclantherinae, such as Ayala-Nieto et al. (1988) for Rytidostylis carthaginensis (Jacq.) Kuntze, and Rodriguez-Jiménez & Palácios Chávez (1998) for the genus Echinopepon Naud. However, the most comprehensive study is that of Stafford & Sutton (1994) who described in detail the pollen morphology of species in the subtribe Cyclantherinae and their taxonomic relevance, establishing seven pollen types, and highlighting differences among aperture number, structure and ornamentation of the exine. The work of Khunwasi (1998) includes 8 species of Cyclanthera (incl. Cremastopus) and 8 species of Sicyos.

For Sicyinae, cladistic studies using pollen morphology helped to solve the delimitation of the genus Sechium P. Br. (Lira et al., 1997a, b), now sunken into Sicyos (Schaefer & Renner 2011b).

Although Cyclanthera and Sicyos are among the more important genera of Cucurbitaceae, their pollen morphology is still incompletely known (Marticorena, 1963; Heusser, 1971; Stafford & Sutton, 1994; Herrera & Urrego, 1996; Khunwasi 1998). The main goal of the present study is to describe the pollen morphology of these two genera and make comparisons among species, and thus provide additional information for the understanding of the group.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Pollen samples from eight species of Cyclanthera and three species of Sicyos were obtained from herbarium specimens (see below: Examined material). We tried to use material from the highest number of localities as possible to account for pollen variability.

Pollen samples were prepared using the acetolytic method described by Erdtman (1960). For light microscopy, slides were mounted using glycerinated jelly and sealed with transparent nail polish. The slides are deposited in the Palinological Collection at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul and the Universidade Luterana do Brasil (PAL - ULBRA/Canoas).

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), pollen grains previously acetolized, were mounted on stubs and coated with gold. Some grains were broken following the technique described by Claugher (1986). Samples were analyzed in an electronic microscope PHILIPS XL 20 in the Centro de Microscopia e Microanálise of the Universidade Luterana do Brasil.

The terminology used in pollen descriptions follows Punt et al. (2007).

Examined material

Cyclanthera eichleri Cogn.: BRAZIL. Paraná. Antonina, Rio Cotia, 16-XI-1965, Hatschbach 12780 (MBM). Cyclanthera hystrix (Gill.) Arn.: ARGENTINA. Corrientes. Depto. Paso de Los Libres, 30-X-1973, Schinini 7030 (CTES). Misiones. Depto. Cainevas, 28-VII-1987, Vanni et al. 809 (CTES). BRAZIL. Rio Grande do Sul. Derrubadas, Parque Estadual do Turvo, 25-X-2006, Schmidt s.n. (ICN 146219). Farroupilha, 14-I-1957, Camargo 85 (HAS). Cyclanthera multifoliola Cogn.: BRAZIL. Minas Gerais. Coronel Pacheco, 18-VIII-1945, Heringer 49403 (SP). MEXICO. Chiapas. Nueva Tenochtitlan, 29-X-1989, Lira el al. 961 (MBM). Cyclanthera oligoechinata L.F.P. Lima & Pozner: ARGENTINA. Misiones. Depto. Cainguas, 13-VI-2004, Radins 19 (CTES). BRAZIL. Paraná. Capanema, 15-V-1966, Lindemann 1376 (MBM). Cyclanthera pedata (L.) Schrad.: BRAZIL. Minas Gerais. Lavras, 20-XI-1989, Gavilanes 4387 (ESAL). Paraná. Curitiba, Horto Guabirotuba, 30-XII-1980, Hatschbach 43498 (MBM). Cyclanthera quinquelobata (Vell.) Cogn.: BRAZIL Minas Gerais. Sapucaí-Mirim, 06-XI-1953, Kuhlmann 2898 (SP). Rio Grande do Sul. Tenente Portela, 12-I-1982, Mattos et al. 22943 (HAS). Palmeira das Missões, 21-I-2007, Araújo s.n. (ICN 151349). São Paulo. Santa Isabel, Igaratá, 27-IX-1950, Kuhlmann 2558 (SP); Jundiaí, 23-XII-1956, Kuhlmann 2898 (SP). Cyclanthera tenuifolia Cogn.: BRAZIL. Paraná. Palmas, 14-XII-1980, Hatschbach 43489 (MBM). Rio Grande do Sul. Cambará do Sul, 19-XII-1969, Ferreira & Irgang s.n (ICN 7273). São José dos Ausentes, 28-XII-2006, L.F. Lima 365 (ICN). Santa Catarina. Caçador, Rio Castelhano, 22-XII-1990, Krapovickas & Cristobal s.n (CTES 43707); São Joaquin, Campestre do Malacara, Morro da Igreja, 21-I-1960, Mattos 7043 (HAS). Cyclanthera tenuisepala Cogn.: BRAZIL. Pernambuco. Riacho das Almas, 27-VII-1988, Pereira 261 (IPA). Rio Grande do Sul. Sério, 11-III-2007 Freitas 253 (ICN) ECUADOR. Tungurahua, Valley of Rio Pastaza, 26-VII-1939, Asplund s.n. (MBM 135330). MEXICO. Guerrero. Teletoapan, 13-IX-1991, Lira & Soto 1311 (MBM). Sicyos martii Cogn.: BRAZIL. Ceará. Guaramiranga, 16-VII-1908, Ducke s.n. (MG 1301). Pacotí, 04-VI-1983, Fernandes & Bezerra s.n. (EAC); 26-XI-2001, Chaves & Andrade s.n. (EAC). Goiás. Rio Parnaíba, 20km de Itumbiara, 21-XII-1972, Rizzo 8703 (UFG). Minas Gerais. Juiz de Fora, Água Limpa, Faz. Experimental, XI-1969, Krieger 7903 (MBM). Sicyos polyacanthus Cogn.: BRAZIL. Ceará. Independência, 22-V-2008, Vieira Neto 170 (ICN). Paraná. Siqueira Campos. Ribeirão do Veado, 28-3-1974, Kummrow 471 (MBM). Rio Grande do Sul. Parque Estadual do Turvo, 31-X-1971, Lindemann et al s.n. (ICN 8889). Porto Alegre, 20-XI-2006, Kinupp 3203 (ICN). Sicyos warmingii Cogn.: ARGENTINA. Catamarca. Dpto Ambato, 29-III-1995, Saraiva-Toledo et al. 13109 (MBM). Salta. Depto. San Martin, 31-V-1980, Pedersen 12871 (MBM).

RESULTS

Cyclanthera has pollen grains with a polar mean diameter of 51.40 µm and equatorial mean diameter of 49.10 µm, a prolate-spheroidal shape (P/E = 1.11), frequently 4-7 zonocolporate with circular endoaperture, punctitegilate exine, with enlargement in the center of the mesocolpia, where collumeles are evident Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 1. Selected characters of Cyclanthera pollen, including dimensions (µm) and morphology, with references to illustrations. Abbreviations: Apert, apertures; Ex, mean value of exine thickness; O sph, oblate spheroidal; P sph, prolate spheroidal; Sp, subprolate.

Fig. 1. Light microscopy images of Cyclanthera pollen grains. A-D, C. eichlerii. A-B, polar view. C-D, equatorial view. E-F, C. hystrix. E, polar view. F, equatorial view. G, C. multifoliola, polar view. H, C. oligoechinata, equatorial view. I, C. pedata, polar view. J-K, C. quinquelobata. J, polar view. K, equatorial view. L-M, C. tenuifolia. L, polar view. M, equatorial view. N-P, C. tenuisepala. N-O, polar view. P, equatorial view.

Fig. 2. SEM images of Cyclanthera pollen grains. A, C. eichlerii, equatorial oblique view showing details of the apertures and ornamentation. B-C, C. hystrix. B, polar oblique view showing details of the apertures and ornamentation. C, equatorial view. D-E, C. oligoechinata. D, section of pollen grain, showing endoaperture and exine structure. E, exine structure. F, C. pedata, detail of the aperture. G-H, C. quinquelobata. G, equatorial oblique view. H, details of the apertures and ornamentation. I-J, C. tenuifolia. I, polar oblique view. J, equatorial oblique view. K-M, C. tenuisepala. K, details of the apertures and ornamentation. L, polar view. M, details of the ornamentations.

Cyclanthera eichleri, C. pedata and C. tenuisepala have the highest pollen grain dimensions. C. oligoechinata has pollen grains with a smaller polar mean diameter, while C. hystrix and C. tenuifolia have the smallest means for the equatorial diameter (Table 1). Within Cyclanthera, there is a tendency of having a grain with subspherical shape, and shapes varying from oblate spheroidal (Fig. 1H) to subprolate (Fig. 1C-D, F, P). In relation to the exine, a thickness between 4 to 5 µm is most common. The number of apertures among the studied species varied between 4 and 6. C. eichleri (Fig. 1A-B) and C. oligoechinata have predominantly 5 apertures, C. tenuisepala (Fig. 1N-O) frequently has grains with 5 or 6 apertures, C. hystrix (Fig. 1E), C. multifoliola (Fig. 1G), C. quinquelobata (Fig. 1J), and C. tenuifolia (Fig. 1L) have 4 apertures, and in C. pedata, pollen grains have 4 or 6 apertures, rarely 5 (Fig. 1I).

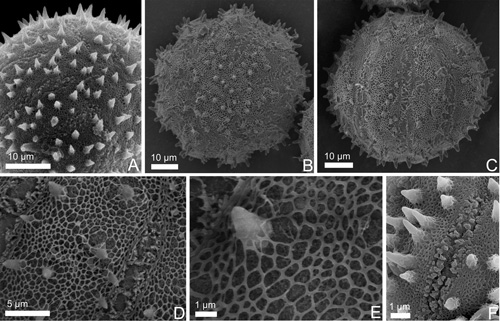

Species of Sicyos are characterized by the presence of pollen grains with a polar mean diameter of 50.6 µm and an equatorial diameter of 61.3 µm, an oblate-spheroidal shape, invariably P/E = 0.88 (Table 2), 8-12 colpate with an echinate exine supra and microreticulate (Figs. 3 and 4).

Table 2. Selected characters of Sicyos pollen, including dimensions (µm) and morphology, with references to illustrations. Abbreviations: Apert., Apertures; Ex, Mean of exine thickness; O sph, Oblate spheroidal.

Fig. 3. Light microscopy images of Sicyos pollen grains. A-C, S. martii. A, polar view, showing the apertures and spines. B, polar view, equatorial focus level. C, equatorial view. D-G, S. polyacanthus. D, polar view. E, polar view, equatorial focus level. F, equatorial view. G, equatorial view, showing exine and spines. H-I, S. warmingii. H, polar view, showing the apertures and spines. I, polar view, showing exine.

Fig. 4. SEM images of Sicyos pollen grains. A, S. martii, polar oblique view. B-E, S. polyacanthus. B, polar view. C, equatorial view. D,: details of the apertures and ornamentation. E,: detail of the ornamentation. F, S. warmingii, details of the apertures and ornamentation.

Among the studied species, pollen grains of Sicyos polyacanthus have generally the highest polar and equatorial diameters, and S. martii the lowest values (Table 2). In this genus the exine is thin and the spines, with length and shape of the apex variable among species, always have a translucid cavity in the apex (Fig. 3G). S. martii has smaller spines with a pointing apex (Table 2, Fig. 3C); in S. polyacanthus and S. warmingii the spines are longer, being robust with a round apex in the former, and thin with a pointing apex in the latter (Table 2, Fig. 3F,I). There is a high number of colpi in S. martii, and a smaller number in S. polyacanthus and S. warmingii (Table 2).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The present study supports the division of Sicyoeae into two subtribes based on pollen morphology, confirming the importance of this diagnostic characteristic for the definition of sub-tribes as pointed out by Jeffrey (1990).

Two pollen types were observed in Sicyoeae: one for Cyclanthera species, with puctitegilate and multicoporate pollen grains (type Cyclantherinae, sensu Jeffrey, 1964) and the other for species of Sycios, with echinate and multicolpate pollen (type Sicyinae, sensu Jeffrey, 1964). These two pollen types are also observed in other species and genera of the tribe (Marticorena, 1963; Shridhar & Singh, 1990; Alvarado et al., 1992; Stafford & Sutton, 1994; Lira et al., 1997a; Rodríguez-Jiménez & Palacios Chavez, 1998; García et al., 2003; Khunwasi 1998).

Comparing our data with the results presented by Khunwasi (1998), there is a compatibility between the characters discussed in both works. There is a discrepancy in measures of exine thickness for the species of Cyclanthera, where Khunwasi (1998) considered a variation between 7-8.4µm, while in the present study we consider a variation between 3.9-5.4µm, in the apocolpus region. This incongruence probably is provenient of measures in different regions of the pollen grain, since the mesocolpus is thickened in species of Cyclanthera.

The number of apertures in the pollen grains is variable in both studied genera, with higher amplitude observed in Sicyos (8-12 apertures) compared to Cyclanthera (4-6 apertures). Rodríguez-Jiménez & Palácios-Chavéz (1998) observed a highest variation (6-17 apertures) in Echinopepon (Cyclantherinae). However, Marticorena (1963), Alvarado et al. (1992), and Lira et al. (1997a, b) reported for other species of Sicyinae a lower variation in the number of apertures, different from what was observed for Sicyos.

In relation to the structure of the sporoderm of Cyclanthera, this study shows similarities with the Cyclanthera type proposed by Stafford & Sutton (1994), which includes, in addition to Cyclanthera, species of Marah Kellog, Elateriopsis Ernst, and Hamburia Seem. In these taxa, as well as in the species studied here, the exine is punctitegilate and the collumels are long.

In Sicyos the interpretation of the sporoderm is not clear, especially in relation to the interspinal area. Marticorena (1963) described for the pollen grains of the genera of Sicyineae "echinate or echinulate exine, covered by an apparently loose coat, formed by baculoid processes, which in some species, have a loosely reticuloid disposition". In the present study, we observed, with scanning microscopy, that the interspinal ornamentation referred by Marticorena (1963) is a microreticulum.

The presence of cavities inside the spines as observed for our Sicyos species is also reported for other species in the genus and in Sicyieae (Marticorena, 1963; García et al., 2003). However, García et al. (2003) observed cavities located at the base of the spines in Sicyos parviflorus Willd. Alvarado et al. (1992) and Lira et al. (1994; 1997a, b) did not confirm the presence of cavities in all individuals of the tribe, restricting its occurrence to the genus Sechium and to the species Sechiopsis triquetra (Ser.) Naudin. The presence or absence of these cavities are informative in the delimitation of genera and in phylogenetic studies by Lira et al. (1997a, b). However, the presence of this characteristic seems to be more widespread than considered by these authors.

Other potential characteristics for phylogenetic studies, due to their variability, are the shape of the apex and the length of the spines. These characteristics were used in this type of study by Lira et al. (1997b) for Sechium.

According to data from molecular phylogeny and the new proposed classification of Cucurbitaceae (Schaefer & Renner, 2011a), the genera Sechium, Sechiopsis Naudim, Pterosicyos Brandegee, Sicyosperma A. Grey, Sicyocaulis Wiggins, Parasicyos Dieterle and Costarica L. D. Gómez are synonymized in Sicyos, supporting the general pollen morphology. Just like the pollen morphology of Pseudocyclanthera Mart. Crov. and Rytidostyles Hook. & Arn.(Stafford & Sutton, 1994) strengthen the proposed inclusion of these two genera in Cyclanthera (Schaefer & Renner, 2011a).

In the first study on molecular phylogeny of Cucurbitaceae (Kocyan et al., 2007) the 20 sampled taxa of Sicyoeae form a clade that, according to the authors, is well supported by morphology, including pollen characteristics such as the presence of exine finely spinulose and colpate or colporate grains. As demonstrated in several pollen studies (Marticorena, 1963; Stafford & Sutton, 1994; Rodríguez-Jiménez & Palacios Chávez, 1998; Lira et al., 1997a) and in this work, species of Cyclantherinae do not have an echinate exine.

According Cogniaux (1878), Sicyos is divided in two sections based on the arrangement of flowers with pistils, on the shape of the fruits, and on spine peculiarities: Section Sicyos (to which belong S. polyacanthus and S. warmingii) that has aggregated pistillate flowers in umbellas, ovoid or oblong fruits and scabrous and retrorses spines, and Section Atractocarpos (which includes S. martii), with pistillate flowers solitary or geminate, fusiforme fruits, and arrow shaped spines. In addition, some species have been placed in Anomalosicyos, a genus described by Gentry (1946) to accommodate species of the section Atractocarpos. Thus, due to the lack of a recent review for this genus, the last was made by Cogniaux (1881), and due to the difficult taxonomy, a pollen study that includes a higher number of taxa is desirable to help elucidate several questions. Even though we analyzed a restricted number of species in the present study, it is possible to observe that these species form a group in the sections proposed by Cogniaux (1881). Sicyos martii presents the smallest dimensions of pollen grains and spines and the highest number of apertures when compared with S. polyacanthus and S. warmingii, in which pollen grains are larger, spines are longer, and the number of apertures is smaller.

The present study highlights the importance of the use of pollen characters for distinguishing subtribes of Sicyoeae, as suggested by Shridhar & Singh (1990) for higher hierarchical levels in Cucurbitaceae. Most important for the distinction of species or species groups are the number and type of apertures, pollen dimensions, ornamentations, and structure and thickness of exine.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTSS

The authors would like to thank the curators of the herbariums consulted for the pollen samples and Msc. Greta Aline Dettke for her help in figure preparation and manuscript revision. This work is part of the Programa de Taxonomia (PROTAX/CNPq), process number 56.3949/2005-8, and part of the Ph.D. thesis in Botany developed by the first author.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Ayala-Nieto, M. L.; R. Lira Saade & J. L. Alvarado. 1988. Morfologia polinica de las Cucurbitaceae de la Peninsula de Yucatan, Mexico. Pollen et Spores 30: 5-28. [ Links ]

2. Alvarado, J. L.; R. Lira & J. Caballero. 1992. Palynological evidence for the generic delimitation of Sechium sensu lato (Cucurbitaceae) and its allies. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) 22: 109-121. [ Links ]

3. Claugher, D. 1986. Pollen wall structure, a new interpretation. Scanning Electron Microscopy 1: 291-299. [ Links ]

4. Cogniaux, A. 1881. Cucurbitacées, in A. De Candolle & C. De Candolle (eds.), Monographiae Phanerogamarum, vol. 3, pp. 325-951. Paris: Masson. [ Links ]

5. Erdtman, G. 1960. The acetolysis method. A revised description. Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift 39: 561-564. [ Links ]

6. García, D. L. Q.; C. L. Hernández & M. De La L. A. Sánchez. 2003. Morfología de los granos de polen de la familia Cucurbitaceae del Estado de Querétaro, México. Polibotánica 16: 29-48. [ Links ]

7. Gentry, H. S. 1946. Anomalosicyos, a new genus in Cucurbitaceae. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 73(6): 565-569. [ Links ]

8. Herrera, L. F. & L. E. Urrego. 1996. Atlas de pollen de plantas cultivadas de la Amazonía Colombiana. Colombia: Tropenbos. [ Links ]

9. Heusser, C. J. 1971. Pollen and spores of Chile: modern types of Pteridophyta, Gymnospermae and Angiospermae. Tucson: Univ. Arizona Press. [ Links ]

10. Jeffrey, C. 1990. Systematics of the Cucurbitaceae: an overview, in M. D. Bates; R. W. Robinson & C. Jeffrey (eds.), Biology and utilization of the Cucurbitaceae, pp. 3-9. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

11. Jeffrey, C. 2005. A new system of Cucurbitaceae. Botanicheskii Zhurnal. Moscow & Leningrad [St. Petersburg] 90: 332-335. [ Links ]

12. Kocyan, A.; L. Zhang; H. Schaefer & S. S. Renner. 2007. A multi-locus chloroplast phylogeny for the Cucurbitaceae and its implications for character evolution and classification. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44: 553-577. [ Links ]

13. Lira, R.; J. L. Alvarado & J. Castrejón. 1994. Nota sobre el polen de Sechium chimantlense Lira & Chiang y Parasicyos dieterleae Lira & Torres (Cucurbitaceae). Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 54: 275-280. [ Links ]

14. Lira, R.; J. L. Villaseñor & P. D. Dávila. 1997a. A cladistic analysis of the subtribe Sicyinae (Cucurbitaceae). Systematic Botany 22: 415-425. [ Links ]

15. Lira, R.; J. Caballero & P. D. Dávila. 1997b. A contribution to the generic delimitation of Sechium (Cucurbitaceae, Sicyinae). Taxon 46: 269-282. [ Links ]

16. Marticorena, C. 1963. Material para uma monografia de la morfologia del pólen de Cucurbitaceae. Grana Palynologica 4: 78-91. [ Links ]

17. Nee, M. 2004. Cucurbitaceae, en N. Smith; S. A. Mori; A. Henderson; D. Wn. Stevenson & S. V. Heald (eds.), Flowering Plants of the Neotropics. pp 120-121. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

18. Punt, W.; P. P. Hoen; S. Blackmore; S. Nilsson & A. Le Thomas. 2007. Glossary of pollen and spore terminology. Review of Paleobotany and Palynology 143: 1-81. [ Links ]

19. Rodríguez-Jiménez, C. & R. Palacios Chávez. 1998. Pollen morphology of the genus Echinopepon (Cucurbitaceae). Sida 18: 479-491. [ Links ]

20. Schaefer, H.; C. Heibl & S. S. Renner. 2009. Gourd afloat: a dated phylogeny reveals an Asian origin of the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae) and numerous oversea dispersal events. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276: 843-851. [ Links ]

21. Schaefer, H. & S. S. Renner. 2011a. Phylogenetic relationships in the order Cucurbitales and a new classification of the gourd family (Cucurbitaceae). Taxon 60: 122-138. [ Links ]

22. Schaefer, H. & S. S. Renner. 2011b. Cucurbitaceae, in K. Kubitzki (ed.), The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants, Volume 10: Flowering Plants: Eudicots - Sapindales, Cucurbitales, Myrtaceae. Berlin: Springer. [ Links ]

23. Sebastian, P.; H. Schaefer & S. S. Renner. 2010. Darwin's Galapagos Gourd: Providing new insights 175 years after his visit. Journal of Biogeography 37: 975-980. [ Links ]

24. Shridar, S. & D. Singh. 1990. Palynology of the Indian Cucurbitaceae, en M. D. Bates; R. W. Robinson & C. Jeffrey (eds.), Biology and utilization of the Cucurbitaceae, pp. 200-208. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

25. Stafford, P. J. & D. A. Sutton. 1994. Pollen morphology of the Cyclantherinae C. Jeffr. (tribe Sicyeae Schrad., Cucurbitaceae) and its taxonomic significance. Acta Botanica Gallica 141: 171-182. [ Links ]