KEY POINTS

• The diagnosis of a neck mass is usually a challenge, with age being the main clinical factor to be considered. Neck masses have been extensively studied in children, adolescents, and adults, but studies clearly addressing this issue in aged patients are still scarce.

• In this study, we describe the distribution of diagnoses in a series of 273 aged patients and evaluate nine dif ferent semiological features and their association with malignancy. Malignant (38%) and benign neoplasm (34%) were the most common diagnoses, followed by inflammatory (30%) and congenital lesions (5%). Age, male sex, history of cancer, mass fixation, and mass involvement with multiple cervical lymph node levels were identified as semiological features associated with malignancy.

Neck masses are a common reason for consultation among adult patients1. These are defined as abnormal le sions (congenital or acquired) that are visible, palpable, or evident through diagnostic imaging studies1. The diagnosis of a neck mass is usually a challenge, and age is the main clinical factor to be considered2. An asymptomatic mass in the neck of an adult patient is often the first manifesta tion of a malignant disease1. Neck masses have been extensively studied in children, adolescents, and adults, but studies clearly addressing this issue in aged patients remain scarce3,4. In this context, the aims of our study were to describe the distribution of diagnoses in patients over 65 years of age who presented for neck masses and to identify semiological features associated with malignancy.

Materials and methods

We conducted a descriptive retrospective study including 273 consecutive patients with neck masses. In an electronic database, we identified patients over 65 years of age who presented to the maxillofacial surgery department of Dr. César Milstein Hospital between January 2008 and December 2018 and whose chief complaint was a neck mass. The Dr. César Milstein Hospital is a tertiary teaching hospital that exclusively provides care to patients covered by government health in surance for retirees and pensioners (The National Institute of Social Services for Retirees and Pensioners, INSSJP) and, consequently, the vast majority of patients who attend are over 65 years of age. Patients with previously diagnosed malignant tumors of the aero digestive tract and patients with thyroid disease were excluded.

The following variables were retrospectively recorded: age, sex, history of cancer, history of tobacco smoking, presence of pain, location and size of the mass, bilaterality, whether or not the mass was fixed to either the deep tissues or the skin, and the final diagnosis. Continuous variables were recorded as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and interquartile range (IQR), according to the distribution of the data. Categorical variables were recorded as proportions. The location of the mass was determined by clinical examination and recorded as a nominal categorical variable; the categories were established according to the classification system pub lished by the American Society for Head and Neck Surgery and the American Academy of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery in 20025. The diagnosis was recorded as a categorical variable. The following categories were evaluated: benign neoplasms, malignant neoplasms, congenital pathol ogy, and inflammatory pathology. Neoplastic processes and congenital lesions were diagnosed through fine-needle aspira tion cytology or open biopsy and histopathological evaluation. When lymphoproliferative disorders were inferred from clinical examination or imaging studies, a flow cytometry test was routinely used. Inflammatory conditions were diagnosed on the basis of clinical or imaging signs of infection or inflammatory pathology. These conditions were diagnosed and managed following standard procedures. The diagnostic algorithm is outlined in Figure 1.

To identify semiological features associated with malig nancy, a multiple logistic regression model was performed. The following variables were evaluated in the crude analysis: age, sex, history of cancer, history of tobacco smoking, pain, mass size, bilaterality, mass fixation to either the deep tissues or the skin, and mass involvement with multiple cervical lymph node levels. The variables that reached statistical significance in the crude analysis were included in the final multivariable model. Using the estimation of Peduzzi et al6 and considering a total of 65 malignancy events, a maximum of 6 variables were included in the model, given a fixed sample size. For the analysis of the secondary objective, we used a complete case analysis (n = 181). For the analysis, we used the Stata sta tistical package (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Our study was approved by the Dr. César Milstein Hos pital Institutional Review Board (Register Number 1562) and was conducted in accordance with ethical principles for medical research in humans as established in the 2013 version of the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

Results

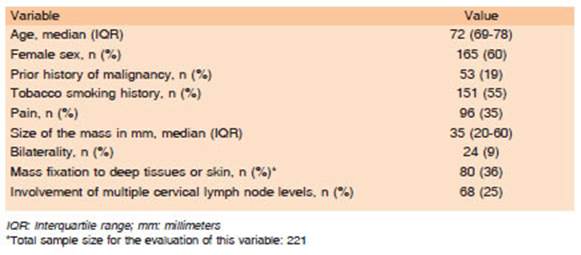

Two hundred eighty-nine patients were assessed for inclusion. Sixteen patients were excluded. The flowchart of patients included is shown in Figure 2. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients included are presented in Table 1. Neck masses were categorized as congenital lesions (n = 7, 3%, 95% CI: 1%-5%), in flammatory masses (n = 67, 25%, 95% CI: 19%-30%), benign neoplasms (n = 77, 28%, 95% CI: 23%-34%), and malignant neoplasms (n = 87, 32%, 95% CI: 26%-38%). In a subset of the patients, it was not possible to reach a definitive diagnosis because they had discontinued care (n = 35, 12%). The distribution of the diagnoses within each group is presented in Table 2.

In the logistic regression analysis for the identification of semiological features associated with malignancy, the following variables were statistically significant: age, male sex, history of cancer, mass fixation to either the deep tissues or the skin, and the involvement of the mass with multiple cervical lymph node levels. Table 3 shows the crude and adjusted analysis of the evaluated semiological features associated with malignancy (n = 181).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated 273 aged patients whose chief complaint was a cervical mass. Malignant neoplasms were the most frequent diagnoses, followed by benign neoplasms and inflammatory and congenital lesions.

Although the scientific literature has consistently point ed out that malignant lesions are more common than any other etiology of neck masses in patients over 40 years of age, the proportions of malignant tumors reported in this age group vary widely between 16% and 80%2,7-9. This variability may be explained by differences in the characteristics of the patients included, the diagnostic criteria used, or the setting in which the studies were car ried out. In the present study, we report the distribution of diagnoses in a cohort consisting exclusively of patients over 65 years of age. In agreement with other research ers, we found that lymphomas and cervical lymph node metastases from carcinomas were the most frequently occurring malignant lesions8. We also found a high pro portion of benign neoplasms, which may be related to the high prevalence of benign salivary gland tumors in our cohort. Inflammatory masses ranked third in frequency in our study, and sialadenitis -a condition frequently affecting aged patients10- was the most common inflam matory lesion. The low frequency observed for congenital lesions coincides with results reported by other authors for patients over 40 years of age2.

Clinical risk factors for malignancy described in the literature include age over 40 years, male sex, mass fixation, mass size, B symptoms, ulceration of the skin, and prior history of cancer and smoking, among others1,7,11,12. In our study we evaluated the influence of nine dif ferent semiological features. Age, male sex, prior history of cancer, mass fixation to either the deep tissues or the skin, and the involvement of the mass with multiple cervical lymph node levels were identified as associated features with malignant neoplasms.

Our study has some limitations. Since it was carried out in a tertiary teaching hospital, results are probably affected by underlying referral bias. Missing data for the secondary analysis may be regarded as an additional limitation, as thirty-three percent of patients had at least one missing data point. Since we assumed that the missing data were missing at random, we decided to use a complete case analysis approach. Conversely, our study has several strengths. The patients included may appropriately represent the population of aged patients. Semiological features associated with malig nancy were specifically addressed in a large sample of patients through a robust regression method, which allowed for adjustment for potentially confounding fac tors. Overall and despite study limitations, our results are consistent with the literature and are supported by clear biological plausibility, as the association of increased risk of malignancy and aging has been ex tensively demonstrated1,3,7-9,13,14.

When evaluating a neck mass in an elderly patient, a neoplastic origin should be strongly suspected. The suspi cion of malignancy increases in the presence of advanced age, male sex, prior history of cancer, mass fixation to the surrounding tissues, and mass involvement with multiple cervical lymph node levels.