KEY POINTS

Current knowledge

• Cancer patients have multiple and complex needs that will be timely addressed at different healthcare system levels.

• These patients are late or not referred to specific services and die with unrelieved suffering.

• The NECPAL tool is validated for screening and early identification of patients with life-limiting diseases. It combines palliative and prognosis approach.

Contribution of the article to current knowledge

• We designed and implemented a demonstration cancer programme that could be replicated in different settings.

• We proposed a proactive palliative approach using the NECPAL as screening tool, and the continuity of care until death when possible.

• A predictive model was feasible improving chances for timely palliative care referral and needs approach.

In 2020, an estimated 19.3 million new cancer cases and nearly 10 million cancer deaths oc curred worldwide1. Patients have multiple and complex needs that will be addressed at different healthcare system levels2. Argentina has a medium-high cancer incidence, with over 100 000 new cases per year3. It is ranked seventh in terms of incidence and third in terms of mortal ity among countries of Latin America4. Nowa days, only 14% of patients with palliative care (PC) needs have access to specialized services in the country5. The National Palliative Care Programme for cancer patients, launched by the National Cancer Institute in 2016, “promotes continuous and integrated care throughout the disease trajectory, focusing on the prevention and relief of suffering and achieving the best possible quality of life for patients and their families”6. So far, the number of cancer patients with palliative needs in Argentina remains un known. There are no standardized screening processes for the early identification of the tar get population and their palliative needs. Furthermore, there is no systematic review and documentation model of interventions seeking better effectiveness and quality assessment. Consequently, patients with palliative care needs are late or not referred to specific services and die with unrelieved suffering.

The WHO defines PC as improving quality of life (QoL) through early detection and impec cable needs assessment, which will enable pro fessionals to set an efficient, timely, continuous, and integrated care plan7. The practical PC ap proach should be an informed and always avail able option8-10. Furthermore, prognostic factors may contribute to achieving a more accurate multidimensional case management11-13. Simple well-validated predictive tools that identify in dividuals at high risk of death and comparative outcomes indicators are required14,15.

Growing evidence shows that the NECPAL CCOMS-ICO© tool (in Spanish, NECesidades PA Liativas; in English, Palliative Needs) is a validat ed screening instrument for the identification of patients with life-limiting diseases in need of PC2,10,11,16,17. It is based on the “surprise ques tion” (SQ)- Would you be surprised if this patient dies in the next year?- and comprises profession als’ consideration, patient or family’s perceived need or desire, and other general or specific se verity and clinical progression parameters. It assists healthcare professionals by encouraging systematic patient screening, estimating preva lence, and implementing assistance. It is the es sence and first step in comprehensive care12,18-20. Moreover, some NECPAL parameters have been independently associated with mortality risk in different populations11-13,21.

In 2015, we implemented a small-scale study, called NECPAL1, to test the feasibility of the screening tool and the continuity of care in one university hospital in Buenos Aires City10. That experience provided valuable insight to repli cate and scale up this systematic approach as an effective and practical model for appropriate needs addressing into different settings.

The present study, called NECPAL2, aimed to design and implement an integrated PC model (PCM) in three hospitals in the same city. We report a two-year healthcare intervention and its implementation process. It is a demonstra tion multi-site and multi-level programme that includes patients’ follow-up through hospi tal facilities and until death when possible. If home-care was feasible and consented to, it was provided by a home-based care team. This project included palliative and prognosis ap proaches.

Materials and methods

The NECPAL2 was a prospective longitudinal observa tional study. It was designed and implemented in public hospitals located in Buenos Aires from 2016 to 2018. Three palliative hospital-based care teams and one home-based care team were involved: the Medical Research Institute A. Lanari, the Institute of Oncology A. Roffo and C.B. Uda ondo Hospital of Gastroenterology. The two first institutes are affiliated with the University of Buenos Aires; mean while, the third one depends on the City Government. Pallium Latinoamérica is a non-profit PC organization that runs a home-care programme within the city.

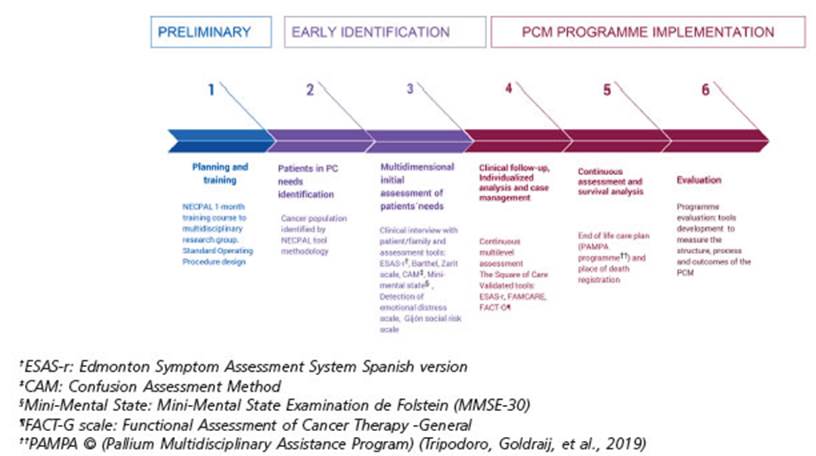

The project was developed in three consecutive stages and six phases (Figure 1): A) Preliminary stage (phase 1), B) Early Identification stage (phases 2 and 3), and C) Im plementation stage (phases 4, 5 and 6) The NECPAL tool was used as screening instrument10. In addition, STROBE statement checklist for observational research guided this report22.

A) Preliminary stage: planning, preparing and training

Phase 1: A multidisciplinary research group was estab lished. Researchers followed a specific one-month train ing course on implementation procedures and concurred with operational definitions based on the NECPAL sys tematic screening methodology10,23. After ethical approv als, researchers, oncologists and PC teams discussed and agreed the protocol in each centre.

B) Early Identification stage

Phase 2: Patients with PC needs identification

Accessible population and sample definition: All ≥18-year-old in/out cancer patients assisted by oncolo gists, gynecologists, urologists and clinicians at the three centres between June 2016 and July 2018. The sample was defined by the NECPAL CCOMS-ICO 3.0 methodology23. Oncologists, oncology nurses, gynecologists, urologists and clinicians were interviewed and asked about adult cancer patients under their care. Additionally, profes sionals consulted patients’ clinical records for sociode mographic or medical information within the meeting. Interviews lasted 10 minutes on average for each case.

NECPAL tool methodology: This instrument offers a non-dichotomous multifactorial, quantitative and quali tative assessment method that incorporates subjective perception and the SQ: Would you be surprised if this patient dies in the next year? Positive answers (SQ+) meant that the doctor would not be surprised. Table 1 summarizes spe cific indicators and the usage of healthcare resources23. Patients considered NECPAL positive (+) are those SQ+ patients who also fulfilled at least one of the other indicators of the tool. Cancer patients were stratified into four levels10. Level 0 with cancer diagnosis; Level 1 cancer with advanced chronic disease; Level 2 cancer with SQ+; Level 3 cancer with SQ+ and at least one indicator (NEC PAL+). The screening was repeated monthly for new pa tients’ enrollment, including previous NECPAL negative (-) patients whose health condition might have changed. Advanced cancer patients (NECPAL+) who accepted par ticipation were interviewed and followed up until death or study clinical cut-off (phase 3).

Table 1 General indicators of severity and progression and disease-specific indicators of NECPAL CCOMS-ICO© tool V 3.023

Operational definitions:

I. Advanced stage of the disease: with progressive and gradual course, with varying degrees of impairment of autonomy and QoL. Variable response to a specific treat ment, progressing towards death in the medium term.

II. Advanced oncological disease: (based on NECPAL criteria) (at least one criterion is required)

- Confirmed diagnosis of metastatic cancer (stage IV) or stage III with poor response or contraindication to a specific treatment, evolutionary flare-up during treat ment or metastatic involvement of vital organs (CNS, liver, massive pulmonary).

- Significant functional impairment (Palliative Perfor mance Scale (PPS) < 50%)24.

- Persistent poorly controlled or refractory symptoms, despite optimization of specific treatment.

III. Terminal oncological stage: an advanced disease in an evolutionary and irreversible phase with multiple symptoms, emotional impact, loss of autonomy, with little or no capacity to respond to specific treatment and with a life prognosis limited to weeks or months, in a context of progressive fragility.

Phase 3: Multidimensional initial assessment of NEC PAL+ patients’ needs

Meetings were appointed between patient-family and researcher for an initial assessment. Semi-structured clinical interviews explored patients’ and families’ mul tidimensional needs according to a qualitative-quanti tative approach25. Each interview lasted for about 40-50 minutes. The following validated scales were applied for systematic assessment: ESAS-r, Zarit scale, Barthel, Con fusion Assessment Method (CAM), Mini-Mental state, Detection of emotional distress scale, Gijón Social Risk Scale26. When the patient had documented cognitive or conscious state impairment, or severe language disorder, interviews were conducted with the patient’s primary carer. In this case, self-administrable scales for patients were not applied. Data were collected on specific encod ed registers, and identified PC needs were summarized in the patient’s medical history after feedback to the on cologist in charge.

C) Implementation Stage

Phase 4: Clinical follow-up, Individualized analysis and case management

The Square of Care model guided the individual as sessment25. It describes the six essential steps in provid ing care: review, information sharing, decision making, care planning, care delivery and confirmation. Assess ment feedback was timely given to treating physicians or teams who would seek the best answer to each patient’s needs. Case management ensured continuity of care ac cording to individual complex needs. Patients were re ferred to the hospital PC service or the home-based care team if appropriate.

Patients and families were reassessed, at least, quar terly using a follow-up set of scales: ESAS-r, FAMCARE scale and QoL FACT-G questionnaire34,35. Register forms with qualitative data were complemented with field notes and encoded to ensure patient and family confi dentiality. All clinical information was included in clini cal records available for professionals in charge.

Phase 5: Continuous assessment and survival analysis

Assessment of the different dimensions on health-re lated QoL was carried out, longitudinally measuring the clinical impact of the palliative intervention according to the clinical situation and recommended criteria (symp tom control, QoL, caregiver burden, sedation, use of re sources, survival and place of death).

When appropriate, we assisted dying patients under a specific care plan based on international standards36. The PAMPA© (from Spanish acronym Programa Asisten cial Multidisciplinario Pallium) care plan for the last days of life was founded on global evidence that identifies the ten key principles for the best care for the dying person and incorporates the 40 outcomes that support quality and safety in individualized patient care (The international 10/40 Model)37,38. A multivariate model with significant indicators in univariate analysis was calculated. Kaplan- Meier survival curves were generated from the date of NECPAL+ identification until death or the last control of that patient. The clinical cut-off was established two years after the first NECPAL+ patient was identified (1st July 2018)11.

Phase 6: Evaluation

Programme evaluation involved a comprehensive assessment of each stage to identify areas for improvement and guarantee the accomplishment of operational aspects and goals achievement. Adjustments were made according to detected needs regarding planning, staff training, interview method, follow-up process, registra tion accuracy, data collection and analysis, and monitor ing of results.

A PC programme can be evaluated using a similar method to that used for PC services; that is, by looking at its structure, activities and outcomes using a quantitative and/or qualitative approach and setting up indicators 39 . Descriptive statistics were carried out to establish PCM indicators to measure structure, process and outcomes of PC resources involved in the project. This PCM was guided by a 23-quality indicator panel developed for our research group in a previous project (10 for structure, 12 for pro cess, 1 for outcome)10,40.

Statistics analysis and ethical approval:

Quantitative data were imported into IBM-SPSS ver sion 22, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL and Stata V12 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for descriptive statistical analysis.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committees of each institution involved. The Necpal2 study was registered at the National Ministry of Health (RENIS IS001867/IS001871), and funded by the Argentine National Cancer Institute and Pallium Latinoamérica.

Results

A total of 2104 cancer patients were screened. Table 2 characterizes the total population pro file per hospital and condition. Furthermore, the flowchart depicts the recruitment process in stratification levels per hospital (Figure 2).

Table 2 Socio-demographic characteristics of the total population profile per hospital and condition

Overall, 681 patients were NECPAL+ (32.3%). Within the three hospital samples, every patient who was SQ+ (Level 2) had at least one general parameter of decline or specific parameter of advanced disease, either cancer or other life-limiting condition (Level 3). Therefore, they were sorted and presented as Level 2 and 3. All NEC PAL+ patients were followed up for two years af ter first identification.

The information was gathered at each of the three hospitals. The data are presented disag gregated per group and hospital due to the het erogeneity of the sample. Comparison between the three hospitals information was beyond this project scope. The demographic and clini cal parameters of NECPAL+ patients underwent descriptive analysis (Table 3). According to distribution, continuous variables were expressed as mean values, standard deviation, median, and range. Almost 70% of the patients were recruited at the oncology department in the gastroenterology hospital. At the other centres, participation of different cancer services was heterogeneous.

Tabla 3 Socio-demographic characteristics of NECPAL+ patients with primary cancer diagnoses and NECPAL parameters per hospital

More than 60% of NECPAL+ patients had a full documented initial assessment. Besides, 65% to 89% of NECPAL+ patients were referred to a PC specialised team. 10% of these patients received home-based care. Home-care delivery was not available beyond Buenos Aires city. Thus, the re ferral was limited due to geographical factors. Roffo and Udaondo are referral centres and have no geographic service area. Several patients came from outside the city (30-40 kilometers away), either for assistance or specialist consul tation. In those cases, follow-up was erratic, and homecare was not an option.

The percentage of patients who presented one or more parameters according to the NEC PAL tool is summarized in Figure 3. Most of the patients (79%) presented less than six parame ters in the whole sample (60% Lanari, 86.6% Ud aondo and 89% Roffo Hospital). However, 21% of the patients presented six or more NECPAL tool parameters (40% Lanari, 13.4% Udaondo and 11% Roffo Hospital).

Within the 2-year follow-up period, 422 NEC PAL+ patients died (61.9%). Survival analysis and Kaplan-Meier curves were published in a pre liminary report12. Patients referred to other cen tres or those lost to follow-up were censored. Hospital-specific survival analysis allows for lo cal interpretation but it is omitted here. Predictable prognostic factors and logistic regression details can be found elsewhere12.

The best predictors of mortality were: nutri tional and functional decline with PPS≤ 50, per sistent symptoms, functional dependence, poor treatment response, primary cancer diagnosis and condition (in/outpatients). Only three vari ables remained significant in multivariate anal ysis: low response to treatment, PPS ≤ 50 and condition (in/outpatients).

The place of death was recorded in 50% to 66% of deaths occurring within the follow-up period. The PAMPA© care plan for the last days of life was comprehensively documented in 91 dying patients (21%). Only two hospitals (Lanari Institute and Udaondo Hospital) and the home-care team had had previous experience with this care plan. Care principles and outcomes were recorded on the patients’ clinical records. Telephone case management was appropriately documented, including post-bereavement calls to the families. PAMPA© outcomes clinical audit has already been published36.

In the evaluation phase, we identified areas for improvement that would allow building a formal quality improvement process and pro viding feedback to attendant teams and stake holders:

- Define the target population profile

- Identify available healthcare services and models of continuity of care across settings (hospital, outpatients’ facilities, home care ser vices).

- Suggest clinical guidelines and protocols for healthcare delivery.

- Select validated tools for multidimensional assessment and end-of-life care plan.

- Define existing standards of health care prac tice.

Structure, process and outcomes indicators were recommended. Process indicators regard ing patient-family care and teamwork, as well as pain assessment (outcome indicator) were reported in clinical records. Therefore, findings are not comparative in terms of the quality of resources themselves, but rather descriptive of examined areas.

As a project deliverable, we created a Pallia tive Approach Model of Implementation (MAP in Spanish) document with recommendations.

Discussion

The strength of this study is the design and implementation of a demonstration programme that could be replicated in different settings and sites in Argentina. We proposed a proactive pal liative approach and the continuity of care until death, which is still not guaranteed in the na tional healthcare system. We believe that the MAP can be customized and reproduced in other centres with similar characteristics in the coun try. Besides study limitations, we believe this model should inspire new cancer care-related national policies. NECPAL2 study contributes to existing evidence by amplifying our previ ous studies results on a multi-site and multi-level scale. It was feasible and measurable. It improved communication among professionals and services and enabled ethical discussion and better quality management.

Critical aspects of contributions analysis are pointed out below:

Early patient identification and need assessment. The NECPAL tool proved to be helpful in the early identification of cancer patients with palliative needs and multidimensional needs assessment. The SQ is widely recognized as a straightforward and effective technique for identifying individu als who are more likely to require PC in their final year of life41-42. The twelve-month SQ accurately predicts death in cancer patients admitted to the hospital43. However, when the time frame is re duced (12, 6, 3 or 1 month before death), its speci ficity increases while its sensitivity decreases. Further research is needed to understand how the SQ is used in practice and whether consisten cy and accuracy could be improved in our setting. Nevertheless, in this study, the SQ and NECPAL parameters were appealing tools for screening patients for PC referral42. It promoted reflexive thinking about potential survival or mortality and triggered a systematic and comprehensive search for unmet needs, including non-physical domains and integrating patient expressed ne cessities2. Surprisingly, in our sample, SQ+ and NECPAL+ patients were coincident. Probably, more experienced or trained physicians are likely to have implicitly in mind advanced cancer in dicators, on which they base their answer to the SQ. The presence of one or more NECPAL indica tors comes to confirm professionals’ perceptions.

Feasibility and acceptability. The screening methodology and follow-up process were fea sible and accepted by healthcare professionals within the research settings. They found the tool practical and easy to complete in a short time in comparison to other prognostic techniques or needs assessment tools42. Furthermore, they agreed that it enabled a multidimensional as sessment without additional burden for pa tients or families.

Case management improvement and PC integra tion. Systematic screening prompted reflexive analysis and holistic case management and im proved timely access and referral to PC services. The programme implementation resulted in a time-efficient method to assess patients and their families, leading to a more sensitive aware ness of their needs and better use of resources to meet them. According to current practice in the country, this PCM had four to six times increased patients’ chances of receiving PC, regardless of the care setting5.

Hui et al. support the need to expand outpa tient PC services in cancer centres and improve early PC referral20,44,45. However, the availability of a PC team does not always mean enough or timely PC attention. Therefore, explicit criteria for referral are needed.

Integration of primary care and hospital-lev el care is a constant challenge in a fragmented healthcare system46. We proposed a flexible care network even in hospitals with no specific geo graphical influence. The non-profit organization synergy, combined with the addition of a home-based programme, enabled us to provide a coordinated response even without administrative facilities.

Regular interviews with professionals and in formation interchange encouraged PC integra tion into the clinical and social services and facili tated continuous care across different healthcare services and levels. Moreover, routine screening exercises, documented multidimensional care priorities and case discussions launched cultural changes in oncologists’ perspectives regarding the unit of care and the role of PC in practice. Fu ture qualitative research should be conducted to look more deeply into this interpretation.

The importance of integrating PC into the healthcare system and providing specialized PC is now recognized by experts to ensure effec tive service delivery for people with PC needs throughout the continuum of care15,45,47-50. Clear referral criteria, interdisciplinary patient care rounds and embedded oncology-PC clinics are examples of potential strategies to promote care integration. PC would benefit nearly 80% of ad vanced cancer patients, enhancing their QoL, re lieving patient and caregivers’ distress, and even improving survival51.

The National Palliative Care Programme pro motes accessibility and integration with on cology in Argentina. Its actions are based on inclusion, equity, and quality principles. How ever, national recommendations focused on the know-how of that integration are lacking6.

Symptom management and communication facili tation. Multidimensional assessment tools aided in eliciting patients’ needs and care preferenc es, thereby in improving communication and clinical decisions with patients and families52. A comprehensive evaluation of needs provided oncologists, clinicians, and other specialists with dynamic information about the unit of care, enabling them to understand the patients’ chang ing situation. From a pragmatic point of view, this approach combined palliative and prognosis evaluation, supporting physicians in their daily practice at clinical and organizational levels53,54.

The NECPAL tool and methodology are based on international standards and evidence, con ducting a good practice approach to prevent and alleviate suffering at the end-of-life. Additionally, NECPAL parameters played a crucial role in prognosis prediction13. Despite the uncertainty in survival, this model proved to assist with prognosis and mortality risk assessment, and it might help clinical decision-making by provid ing an approximate time frame of survival12.

Our mortality analysis along the follow-up period showed that NECPAL+ patients died within the first year (mean global survival: eight months). These survival rates were higher than those in our previous study (mean global sur vival: four months)11. This result raises a new question about the potential impact of the sys tematic approach and reflexive SQ on earlier PC referrals42.

In the new version of NECPAL 4.0 prognosis, identified needs, functional decline, nutritional decline, multimorbidity, increased use of re sources, and specific indicators of disease progression were all significant as prognostic indi cators13. In this way, the group of patients that presented more than six positive parameters (21%) would be expected to have a life expectancy of about four months (following Stage III of NECPAL 4.0)13. Healthcare plans and new integrated and patient-centered care models have been developed globally and tested in other countries53,54.

Information record for monitoring and outcomes evaluation. Data collected would allow scoring and monitoring needs and symptoms over follow-up and objective evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions. Because of their com plexities, all implementation research should consider context-dependent factors that might influence outcomes55. Keeping in mind the characteristics of each hospital, screening NECPAL parameters associated with survival analysis allowed us to build a tailored PCM based on patients´ needs and the resources available in each hospital and in the community.

Quality end-of-life care using international standards36. The active participation of pa tients and families in this program encour aged us to carry out a continuous review. Our PCM allowed us to evaluate and refine con tent towards effectiveness for future imple mentation research projects. Bridging the gap between quality improvement implementers and researchers can increase the generaliz ability of interventions, accelerate the spread of practical approaches, and strengthen im plementers’ local work51,56.

This programme did not constitute a response to the gap between the country’s need and sup ply of PC. Because identifying at-risk individuals with PC needs was based on clinical judgement, selection bias should be assumed. The number of cancer patients with palliative needs in Ar gentina remains still unknown. Subjective and objective information and the success of the screening process depended on the profession als’ commitment to the research. The SQ may help with reflective thinking and increase PC re ferral more than usual. However, it is not neces sarily a bias because the catalytic effect of the SQ has been described as a reflective induction of early PC referral12.

In the geographic area, these three hospitals, in particular, do not have integrated prima ry care teams. In this PCM, the place of death was not always a choice. A substantial number of cancer patients recruited did not live in the city nor the home-care programme geographic area of coverage. All qualitative and quantita tive data supported clinical decision making and case management as a healthcare interven tion. Because we prioritized the PCM design and implementation process, we decided not to re port clinical findings related to validated tools and quality indicator outcomes. They will be addressed in future research reports. Further re search is needed to measure clinical impact.

The implementation of this programme was limited to an accessible population within hos pitals with trained PC teams. Thus, results are poorly generalizable. However, it provided the basis for further implementation research and should encourage policymakers for embracing PCM development and network building for bet ter cancer patient care.

In 2014, the World Health Assembly called to improve access to PC as a core component of health systems, emphasizing on primary health care and community/home-based care7. In ad dition, it recommended building evidence of PC models that are effective in low- and middle-income settings. Furthermore, policymakers should use a needs-based approach to identify patients who require PC and integrate mea surement tools into healthcare professionals’ practice. Encouraging adequate resources for PC programmes and research, particularly in resource-constrained countries, undertakes the next steps in PCM quality improvement efforts57.