KEY POINTS

Current knowledge

• For patients with melanoma microscopic spread to lymph nodes, monitoring with ultrasound has recently been adopted as an alternative to immediate lymphadenectomy. Outcomes of this strategy with adjuvant therapy are now starting to being published in the literature.

Article contribution

• This study provides real-world data of active surveillance in positive-SLN melanoma patients in a reference center in Argentina. Active nodal surveillance was the preferred strategy (almost 80% of our patients) and in case of isolated nodal recurrence, delayed surgery could be performed without post-operative morbidities.

The management of patients with cutane ous melanoma has dramatically changed in the recent decades. Since the first description by Morton in 1992, the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in cutaneous melanoma has be come accepted worldwide1. The results of the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial I (MSLT-1) established the SLNB as a highly prog nostic staging procedure in localized and clini cally node-negative cutaneous melanomas2,3. This technique allowed clinicians to avoid the complications associated with completion lymph node dissection (CLND) in nearly 80% of patients who had a localized cutaneous mela noma and clinically negative regional lymph nodes. Nevertheless, knowing that 80-85% of those with a positive sentinel lymph node (SLN) did not have additional positive nodes after CLND, the indication of immediate surgery be gan to be questioned.

To address this issue, two randomized con trol trials, the Multicenter Selective Lymphad enectomy Trial II (MSLT-2) and German Derma tologic Cooperative Oncology Group sentinel lymph-node Trial (DeCOG-SLT) were conducted. Both demonstrated that immediate CLND per formed after a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy was not associated with improved mela noma specific survival4,5. Patients underwent ul trasonography in the mapped nodal basin and a therapeutic (delayed) lymph node dissection was indicated only in case of nodal recurrence. These trials support a less aggressive approach in stage III cutaneous melanoma with low tu mor burden in the regional lymph nodes. As a result, active nodal surveillance emerged as an option. It is noteworthy that patients included in these clinical trials did not have adjuvant sys temic treatment after lymph node biopsy.

In addition, several trials have evaluated the outcomes of adjuvant systemic therapy in stage III disease. These landmark trials found an im provement in relapse-free survival with the use of anti-programmed death 1 (anti-PD-1) immu notherapy or BRAF/MEK inhibitors but only after complete lymph node dissection6-8.

At this point, a new scenario has arisen in the daily clinical practice in which clinicians need decide to initiate adjuvant therapy and avoid immediate complete lymph node dissection. This treatment strategy is becoming more ac cepted nowadays. In our study, the first objective was to describe the management and adoption of active surveillance in SLN-positive patients since the publication of MSLT-2 Trial. Second, we sought to compare early oncological outcomes; namely, local and systemic recurrence between those who underwent AS and CLND.

Material and methods

Multidisciplinary institutional melanoma tumor board meeting takes place once every week and all cases are discussed. We recommended SLNB in all patients with cutaneous melanoma and a Breslow thickness ≥1mm or ≥0.75mm with associated risk factors (ulceration, high mitotic count, or Clark level invasion IV/V). Since 2020 we discussed the indication in thin melanomas when the probability of nodal metastasis was ≥10% (using the Sen tinel Node Metastasis Risk Prediction Tool developed by Melanoma Institute Australia based on a published risk prediction model)9-10. The surgery requires a preoperative lymphoscintigraphy (involving injection of radioactive colloidal isotope); and the use of blue dye and gamma probe during the surgical procedure as described by Mor ton1. The SLN was defined as the lymph node (or nodes) that first receives direct lymphatic drainage (dye and/or radioactive isotope) from the primary melanoma.

A retrospective evaluation of all procedures between June 2017 and February 2022 at the Sarcoma and Melano ma Unit of our General Surgery Department was carried out. We included patients who had a localized and clini cally node-negative cutaneous melanoma, were aged ≥18 years, underwent SLNB in primary cutaneous melanoma of the trunk and extremities and had at least 1 positive (metastatic) SLN. Those with loco-regional or distant dis ease during the preoperative staging were excluded.

The indication for systemic adjuvant treatment was discussed with the patients after multidisciplinary tumor board evaluation. The immediate CLND was not a require ment to deliver adjuvant treatment. Active surveillance (AS) consisted of physical examination and ultrasound of the mapped node field. Cross-sectional images were performed during surveillance upon discretion of treat ing clinicians. All patients were followed-up according to a usual surveillance protocol performed every 3 months throughout the first 2 years; after that, every 6 months until the 5th year, and then annually.

The main outcome variables were: any-site recurrence free survival (RFS) defined as recurrent melanoma at any site from the time of SLNB, diagnosed by clinical and/or imaging studies and confirmed on biopsy when feasible; isolated nodal recurrence (INR), defined as recurrence in SLN-basin without other affected sites; distant metas tasis-free survival (DMFS), defined as distant metastasis identified during follow-up as either first or subsequent recurrence; and melanoma-specific survival (MSS) de fined as survival until death by disease from time of SLNB.

Approval from the Institutional Review Board was ob tained for this study in view of retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed as part of the routine care. Requirement for specific written in formed consent was waived: however, all patients signed the surgical consent form.

Statistical analysis was carried out with Statistix® and included X2 independence tests and t test for compari son between groups, and a p value <0.05 was considered as statistical significant. Quantitative variables are de scribed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) and qualitative variables as percentages. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

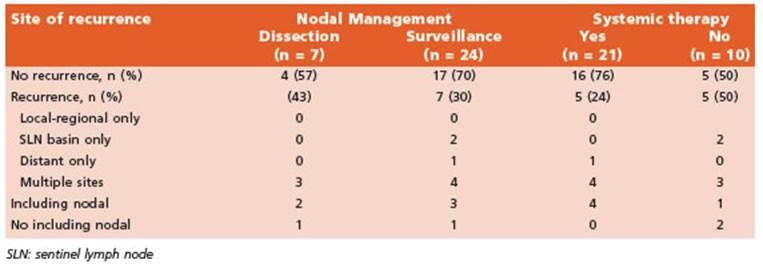

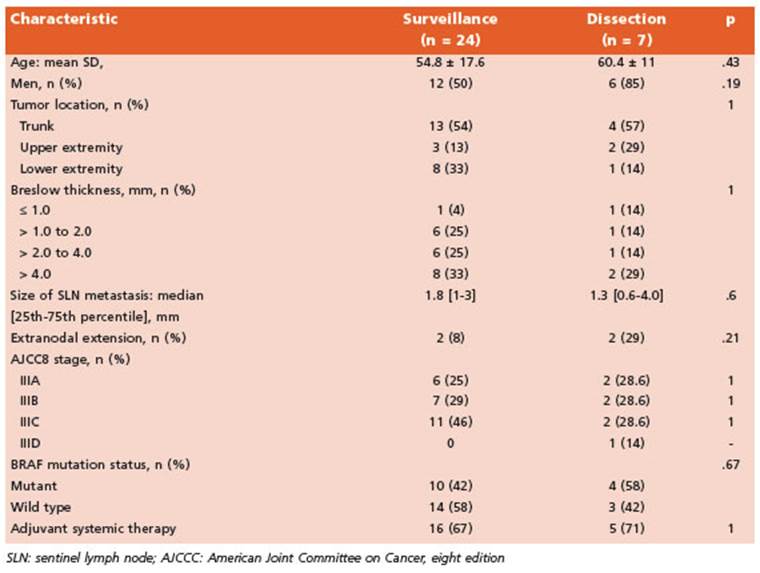

We performed 126 SLNB during the time in terval of our study. Among these, 32 patients (25.4%) had at least 1 positive SLN. We excluded 1 patient due to age < 18 years, leaving a total of 31 patients analyzed. Seven patients (22.5%) un derwent CLND and the remaining 24 (77.5%) re ceived active surveillance (Fig. 1). Characteristics of patients in both groups are listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients undergoing active surveillance vs. completion lymph node dissection

The indication for immediate CLND was high tumor burden in 5 patients and due to multidisciplinary tumor board recommenda tion after case discussion in 2 patients. Among the patients who required immediate surgery, 3 (42.8%) of those 7 had at least 1 positive non- SLN in the completion specimen, which result ed in upstaging, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition cancer staging manual, in 1 of 7 cases (14%). That patient had a T4b lesion with additional positive non-SLNs on CLND and was consequently upstaged from IIIC to IIID.

For patients receiving active surveillance we primarily indicated nodal basin ultrasound ev ery 3 months besides strict physical exam; 16 of the 24 patients (66%) had at least 1 ultrasound during the first 6 months of follow-up. The me dian number of nodal basin ultrasound per pa tient in active surveillance during follow-up was 3 (IQR, 1-6). Moreover, twelve patients (12/24, 50%) had also cross-sectional images during follow-up and all of them where receiving adju vant therapy.

The median follow-up of the whole cohort was 18 (12-32) months. At the final follow-up: 21 patients (68%) were disease-free, 4 patients were alive with disease recurrence and 6 (19%) patients had died (4 of disease progression and 2 of unrelated causes). Estimated 2-yr mela noma-specific survival was 82% (CI 95%, 0.63 - 0.92) with no differences between CLND and AS groups (P = 0.21).

There were 10 (32%) recurrences at any site (Table 2). Estimated 2-yr recurrence free sur vival was 73% (CI95%, 55-86). The proportion of patients who had a recurrence at any site be tween groups was: 43% in the dissection group (3 of 7 patients; median follow-up 15 months) vs. 30% in the AS group (7 of 24 patients; me dian follow-up 18 months). Of the two patients who had isolated nodal basin recurrence, one was detected on clinical assessment and the other detected only by ultrasound. These two patients were receiving active surveillance (2 of 24 patients, 8.3%) without adjuvant therapy and undergone complete (delayed) nodal re section without post-operative morbidities. Estimated 2-yr distant metastases free surviv al of the whole cohort was 76% (CI 95%, 0.57- 0.88); 2 of 7 in dissection group vs. 5 of 24 in AS group. Of the patients with multiple sites recurrences, all but two (5 of 7 patients) were being treated with systemic therapy. Moreover, of those 5 patients, 3 had intra-adjuvant re currences (2/3 were in the active surveillance arm).

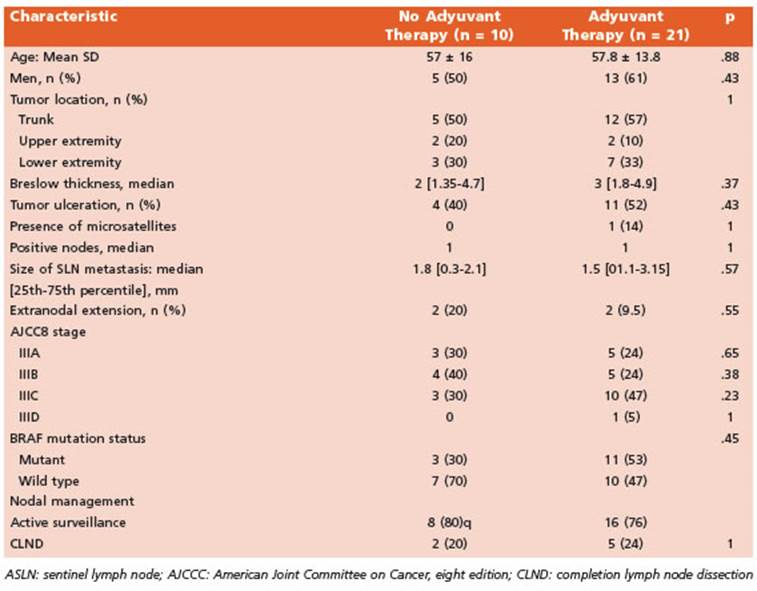

Five of 7 patients (71%) in CLND group and 16 of 24 (67%) patients in active surveillance re ceived adjuvant systemic therapy while 10 pa tients did not, being the main reasons financial issues or lack of approval by the health insur ance (Table 3). Of the patients who had adju vant therapy: 15 completed one year therapy, 3 are presently on treatment and the remaining 3 (13.5%) patients discontinued treatment due to toxicity (fever and severe chills, hepatotoxicity with elevated alanine-aspartate aminotransfer ase and immuno-mediated nephritis).

Single-agent anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was the most common adjuvant treatment (16 of 21 patients, 76%); being nivolumab the most fre quent drug used (13 patients [62%] vs. pembroli zumab, 3 patients [14%]). The remaining 5 (24%) patients received BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

Discussion

In this study of patients with cutaneous mel anoma and positive SLNB, only 22% underwent lymphadenectomy while the rest underwent ac tive nodal surveillance. The percentages of pa tients with recurrence (any site recurrence- or distant metastases- free survival) and disease specific survival were similar between groups; it was noteworthy that almost 70% of patients in AS received adjuvant systemic treatment. We had a low rate of isolated nodal recurrence with AS and all could be salvaged with thera peutic (delayed) lymph node dissection. This big change in the clinical practice started following MSLT-2 Trial publication and we report the real-world experience in a cohort in Argentina.

The management of patients with cutane ous melanoma has changed drastically after the results seen in large Phase III clinical tri als of cutaneous melanoma patients without clinical evidence of regional node metastases. First, the MSLT-1 trial established the prognos tic value of SLNB in patients with intermediate thickness cutaneous melanoma without clini cally detected node disease. Hence, more than 80% of patients with localized disease could avoid an immediate lymphadenectomy and its associated morbidity after a negative SLNB2,3. The possibility to find patients with microscop ic node metastases allowed selecting patients for immediate CLND. Nonetheless, only 15-20% of patients with a positive-SLN had another metastatic node (non-SLN) in the specimen of lymphadenectomy. These findings led to evalu ate the selection of patients in whom to avoid CLND without a negative impact on oncological outcomes and thus reduced morbidity rates11-15.

Results of De-COG SLT and MSLT-2 trials add ed more information about the clinical impact of delayed CLND in patients with positive-SLN. Both randomized clinical trials showed no differ ence in melanoma-specific survival in patients with immediate lymphadenectomy vs control with active surveillance and delayed surgery after the appearance of nodal recurrence4,5. In addition, three randomized control trials evalu ated the outcomes of adjuvant systemic therapy in patients with stage III cutaneous melanoma showing improvement in disease free survival with immunotherapy or target therapy. Those studies randomized only patients with previ ous CLND6-8. At this point, the results of all these trials created a controversy: is there a clinical benefit to undergo immediate CLND in all pa tients with positive-SLNB before starting ad juvant treatment? Different reports have been published evaluating the current management in referral centers.

Broman et al. evaluated 1154 patients with positive SLNB in an international multi-insti tutional study; 189 (16%) underwent lymphad enectomy and 965 (84%) received active surveillance. On multivariable analysis, head and neck location, higher number of positive nodes, larger nodal tumor burden and location of the treat ing center (more frequent in USA and Europe than Australia) were associated with immediate CLND. Reasons for surgery were patient pref erence (41%), surgeon recommendation (18%), burden of disease (32%), difficult in active sur veillance (24%) and for prognostic information (14%). After a follow-up of 11 months, 19% of patients developed recurrence of disease: 19% in the active surveillance group and 22% in the immediate CLND group (p=0.31). There were no differences in distant metastases-free survival according to nodal management or the use of adjuvant treatment15. In another study includ ing 61 positive-SLNBs only 3% of patients un derwent immediate CLND and all remained without disease recurrence. A 13% of recurrence was informed in the active surveillance group16. Bartlett et al. reported 42% of recurrence in 370 patients with positive sentinel node who did not undergo immediate CLND and isolated nod al recurrence in 13.2%12. Farrow et al. reported a recurrence rate of 21.9% (7/32) under active surveillance and adjuvant therapy17. The differ ences in recurrence rates observed in the previ ous series may be due to differences in sample size and time of follow-up between them12,15-17. In our series, seven patients of the cohort (22.5%) had immediate CLND and we registered 32% of recurrences at any site without differences be tween groups. This value is higher than those reported in the literature but may be due to our smaller number of patients.

Broman et al. described that adjuvant sys temic therapy was given in 39% of patients who underwent CLND and 38% who underwent ac tive surveillance. A single agent anti-PD-1 regi men was the most frequent indication. Adju vant therapy was indicated in patients with high risk of recurrence and was associated with a 48% reduction in all-site recurrence15. Nijhuis et al. reported a higher use of adjuvant therapy (52%, 32/61 patients) while Farrow et al. reported its use in 22/32 patients (68.8%)16. In our study, 68% of patients (21 out of 31) received adjuvant systemic therapy and the most frequent indica tion was single-agent anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (77%).

Immediate CLND is associated with some theoretical advantages: best nodal staging and the possibility of avoiding strict nodal follow up with ultrasound. Nevertheless, the upstaging is as low as 5-6% after CLND with more than 80% of patients not having additional positive non- SNs and being exposed to postoperative morbid ity. More important is that there is no evidence that immediate CLND is correlated with survival benefit4,5,18. In addition, unresectable nodal dis ease after active surveillance seems to be ex tremely rare12,15. Finally, nowadays a new clinical dilemma emerges when a patient under active surveillance and adjuvant treatment develops nodal recurrence. These patients will undergo a therapeutic delayed CLND but the indication for discontinuing or resuming the adjuvant treat ment is not yet clearly determined.

Although we have provided some real-world information regarding active surveillance in positive-SLN patients, findings of our study should be taken with caution. The main limi tation of this study is the small size of the co hort and its retrospective design. Also, given the relatively new strategy in this scenario, studies have a short follow-up, and this also limits the ability to draw firm conclusions on the long-term oncologic outcomes. Neverthe less, our findings are similar to those reported in larger retrospective studies that evidence an increasing number of patients in whom an ac tive surveillance approach is preferred after a positive-SLNB.