Wetlands such as the Delta of the Paraná River (hereafter Delta, Fig. 1) are very rich ecosystems that provide multiple services (Mitsch and Gossilink 2007, Cannicci and Contini 2009). These ecosystems are among the most vulnerable to the impact of human activity, being characterized by a higher transfor-mation rate than both terrestrial and aquatic realms (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005, Zedler and Kercher 2005). For instance, about 54% of vertébrate populations that depend on wetlands are decreasing (Dudgeon et al. 2006). In particular, wetland birds are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation (Whited et al. 2000, Riffell et al. 2001, Yuan et al. 2014, Sica et al. 2020), drainage and other types of hydrological al-terations (Deluca et al. 2004, Maclean et al. 2011), and climate change (Chesser 1998). Thus, many wetland species are facing high extinction risks, with the increase of pressure outweighing conservation efforts (CBD 2014). The Delta is a región heavily modified by agriculture (e.g. in the Pampa’s Grasslands and Chaco Forest) and urbanization. The Delta is key for biodi-versity conservation in the region, and aspects such as bird species diversity and conservation status and their relationship with vegetation types are poorly known; therefore, collecting baseline data on species assemblages is critically needed to design manage-ment and/or conservation actions.

The Paraná River Delta is among the most impor-tant wetland macrosystems of the South American southern cone (Bonetto et al. 1986). Its hydrological regime is dominated by floods from the Paraná River, as well as from the Gualeguay and Uruguay rivers. The flood pulses favor an important diversity of en-vironments (Neiff, 1981). Sediment form banks and islands, swamps, estuaries and/or lagoons, and active and inactive lateral and internal channels (Ringuelet 1963, Neiff 1981). This variety of habitats enhance biodiversity (Malvárez 1999) and provide a wealth of ecological services (Baigún et al. 2008). The insular delta landscape before colonization consisted mostly of marshlands with gallery forests along borders of water courses. The remnants of these forests are hi-ghly diverse and include both tropical and temperate species (e.g, Lauraceae) (Kalesnik et al. 2008, Kandus et al. 2016).

Figure 1: Location of the Delta of Paraná River and the different landscape units, a) location of the Delta of Paraná River (rectangle) and of the Del Plata basin (gray area) in South America, b) location of the Lower Delta of Paraná River (rectangle), and c) land uses/land covers and landscape units in the Lower Delta.

The Parana River Delta is a focus of high bird diversity within the Pampas grasslands, which has been mostly transformed into croplands and urbani-zed areas (Baldi et al. 2008). For instance, there are more bird species in the delta (c. 260 species; Bó and Quintana 2011) than in the surrounding landscape outside the floodplain (200 species; Di Giacomo and Contreras 2002). The high bird diversity of the delta is likely related to its biogeographical complexity. In-deed, the delta is at the southernmost extreme of the corridor of tropical biodiversity elements contributed by the Paraná-Paraguay rivers system (Oakley et al. 2005, Nores et al. 2005), and is an area of endemism for some taxa (Apodaca et al. 2019). Some typical tropical taxa have their southernmost distribution limit in this region, such as the Dusky-legged Guan (Penelope obscura) and the Mottle-cheeked Tyrannulet (Phylloscartes ventralis) (Haene and Pereira 2003). In addition, the region likely acts as a biogeographical bridge between the margins of both the Paraná and Uruguay rivers (Kopuchian et al. 2020, Rocha et al. 2020). Finally, the Delta provides habitat for numerous bird species, many of them globally endangered or vulnerable (BirdLife International 2018), such as the Dot-winged Crake (Porzana spiloptera), the Black-and-white Monjita (Xolmisdominicanus) and the Yellow Cardinal (Gubernatrix cristata). Despite the high bird richness of the Delta and the extensive transformations that the area has undergone, regional studies on the ecology, distribution and conservation of its birds are scarce (e.g. Capllonch et al. 2008, Ronchi-Virgolini et al. 2010, De Stefano et al. 2012, Sica et al. 2018, Magnano et al. 2019, Frutos et al. 2020), and a comprehensive understanding of how bird richness relates to the different productive and natural landscape units of the delta is lacking.

The lower delta is the portion at the final stretch of the Paraná River Delta where the Paraná River divides into two main distributary channels (Fig. 1). The most important landscape transformations in this portion began in the 1970’s with Salicaceae plantations (Po-pulus spp. and Salix spp.) inside polders (Borodowski and Suárez 2004, Gaute et al. 2007). Recently, land use patterns have shifted towards more intensive and permanent grazing and silvopastoral systems (Ga-lafassi 2005, Quintana et al. 2014). These activities were accompanied by intensified management based on water control structures such as polders, ditches, pumping systems and levees (Baigún et al. 2008). As a result, between 1999 and 2013, 35% of the freshwater marshes in the area were converted into pastures and forest plantations (Sica et al. 2018). These landscape conversions may have had consequences on wildli-fe distribution and diversity (Quintana et al. 2002, Fracassi 2012, Sica et al. 2018). However, there is a lack of baseline information needed to evaluate these changes in the mid-and long term. Thus, a compre-hensive study on the diversity and ecological require-ments of bird assemblages of the delta, especially the most transformed lower portion, is urgently needed.

Here, we described the composition and conser-vation status of birds of the lower delta of the Paraná River, with emphasis on the relationship between ve-getation type and avian species composition . To meet our objective, we reviewed published field studies and conducted new surveys to elaborate a comprehensive checklist of bird species and evaluate conservation status and their association with vegetation types.

Methods

Study Area and vegetation types

The Paraná River Delta covers the final 300 km of the Paraná Basin, from Diamante City, Entre Ríos (32°4’S, 60°39’W), to the surroundings of Buenos Aires City (34°19’S, 58°28’W; Fig. 1). The climate in the region is humid temperate, with a mean annual temperature of 16.3°C and a total annual rainfall of about 1000 mm (Servicio Meteorológico Nacional 1992). The study area encompasses the lower delta (Fig. 1) that covers approximately 4500 km2 of main-land (southern Entre Ríos Province) and 3000 km2 of islands (northern Buenos Aires Province).

It is divided into five landscape units differing in their hydrological regime, geomorphological setting, and land cover patterns (Malvárez 1999, Kandus et al. 2006; Fig. 1). Four of these landscape units (I, II, III and V) occur in the mainland part of the Lower Delta. Units I and III are characterized by native grass-lands dominated by Panicum miloides and Panicum racemosum, and referred to as Entre Ríos Grasslands (ERG) vegetation type. Xerophytic forest patches are frequent in these units, including native trees such as Vachellia caven and Prosopis nigra. These areas are referred to as Espinillo Forest (EF) vegetation type. Unit II (with subunits a and b) and V are dominated by Freshwater Marshes (FM) covered by bulrushes (Schoenoplectus californicus) together with floating or deeply rooted aquatic vegetation (e.g., Hydrocleys nymphoides, Luziola peruviana), whereas the mid-slo-pes are covered by grasslands (Cynodon dactylon) and upper elevation areas are characterized by EF. The insular area of the lower delta is characterized by Unit IV (with subunits a and b sensu; Kandus et al. 2006). The topographically lower portions of these natural islands are permanently flooded and covered with FM dominated by Scirpus giganteus. Most of the original riparian forests (characterized by abundant nati-ve trees, such as Nectandra angustifolia, Myrsine parvula and Erythrina crista-galli) located on the perimetral levees (Burkart 1957) have been transformed into Sa-lix spp. and Populus spp. plantations (Borodowski and Suárez 2004). Some of these plantations were aban-doned and here are referred to as Secondary Forest (SF) vegetation type; these areas are dominated by the original riparian forest species and invasive exo-tic plant species (e.g. Iris pseudacorus, Lonicera japoni-ca, Ligustrum lucidum, Ligustrum sinense and Rubus spp.; Kalesnik and Malvárez 2004). Mid-slopes towards the center of the islands are marshlands converted to grasslands dominated by patches of both tall and short graminoid species mixed with patches of bare soil and exotic grasses, here referred to as Buenos Aires grasslands (BSASG) vegetation type. Unit IV is highly transformed to implanted forests of Salicaceae that includes: Adult Willow Plantation (Salix spp.; AW) vegetation type, characterized by a high tree density with an understory of two to three shrub layers; Adult Poplar Plantation (Populus spp.; AP) vegetation type, characterized by a lower tree density and fewer (one to two) layers than AW, and the understory domina-ted by herbs and exotic shrubs and trees (Fracassi 2012); and young plantations (Salix spp. and Populus sp. together), here referred to as Young Salicaceae Plantation vegetation type (between three and five5 years; YS), characterized by Salicaceae seedlings and herbaceous species. Along the study area several ri-vers, artificial channels, and streams can be found with open non vegetated water. We consider these as Water Courses (WC).

Data collection

We compiled studies describing bird richness of the Lower Delta and spanning a 13-year period from 2007 to 2020 (Table 1). We excluded surveys carried out before 2007 because they did not represent the current state of bird communities in the Delta since most environments surveyed at that time were sub-sequently transformed. In addition, we only included studies that applied a standard survey methodology (i.e., transects, point counts or mist netting) and that sampled the study area for at least three full days.

We also conducted bird surveys using mist nets, transect counts with binoculars (walking and/or from a vehicle), photographic and song records. On each occasion, we used 4, 8 and 12 m mist nets that were open at dawn and dusk. We studied two locations: Ceibas and Forestal Nucleus (most forested area in the insular Lower Delta). In Ceibas (Islas del Ibicuy and Gualeguaychú, Entre Ríos Province, 33°29’S, 58°41’W), we surveyed landscape units I, IIb, III and V during October and November 2019, totaling 11 days of observations (c. 140 h/net, 16 transects of 400 m and approximately 146 km of road transects). We established four sites: I) Transect from Ceibas to Estancia Ríos de las Aves (road to Ñancay, Gualeguay-chú); II) Estancia San Ricardo, Ceibas; III) Transect from Ceibas to Puerto Ibicuy, through provincial rou-te 45; IV) Transect from Ceibas to public road end. In Forestal Nucleus, (Campana and San Fernando, Buenos Aires Province, 34°3’S, 58°43’W) we performed surveys during September 2019 and January 2020 along landscape unit IVa with a total effort of six days of observation (c.70 h/net) and approximately 90 km of transects. We sampled 2 sites: I) CABBY S.A. Fores-try property, Campana; and II) Nueva Esperanza, San Fernando. Altogether, the compilation of studies and the field surveys carried out for this study covered the different landscape units of the study area (Table 1,Fig. 1).

Data analysis

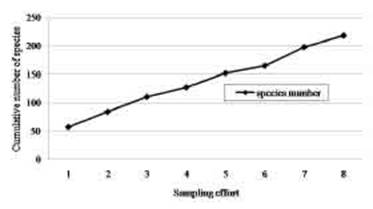

According to the location of each survey, we as-signed each species to the landscape units and vege-tation type where it was recorded. We also assigned a threat status at the national (MAyDS and AA 2017) and international levels (BirdLife International 2021) with the aim of analyzing bird composition and threat status at each landscape unit and vegetation type. We scored a species as rare when it appeared in a single survey. In addition, we considered a species as exclusive if it occupied a single vegetation type. Finally, to assess the completeness of this compilation, we applied a species accumulation curve (Foster et al. 2010) using the specaccum function of the Vegan R package (R Studio Team 2020).

Results The compilation of 12 published studies, and the two field surveys conducted (Table 1) yielded a total of 245 species belonging to 48 families occurring in the lower delta (Tables 1, 2 and Appendix). The species accumulation curve showed a plateau of the number of accumulated species, suggesting that the number of species detected in this work would represent the expected species of the study area (Fig. 2). Neverthe-less, for our final list of species (Appendix), we inclu-ded 8 species which were occasionally found by the authors of this article in the study area but were not mentioned in the published studies nor were they detected in the field surveys conducted in this work: Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), Bicolored Hawk (Accipiter bicolor), White-banded Mockingbird (Mimus triurus), Large Elaenia (Elaenia spectabilis), Black-backed Water Tyrant (Fluvicola albiventer), Grass Wren (Cistothorus platensis), Yellow Cardinal (Gubernatrix cristata) and Fawn-breasted Tanager (Pipraeidea melanonota). Four exotic species were recorded: Graylag Goose (Anser anser), Feral Pigeon (Columba livia), House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and European Starling (Sturnus vulgares).

At the landscape unit level, we detected 133 species for unit I, 73 for unit lia, 171 for unit Ilb, 93 for unit III, 196 for unit IVa, 86 for IVb and 193 for unit V. The landscape unit with the highest count of species with high risk of extinction was IVa with 10 species, followed by V with 6, I with 5, II with 4, IVb with 2, and III with 0 (Table 3).

The vegetation types with the highest count of species were ERG and FM, followed by WC, SF, EF and BSASG (Table 2). Forest plantations presented the lowest number of species, with AP plantations ha-ving the lowest number. Exclusive species (i.e., those recorded in only one vegetation type) amounted to 58 (23.6%), with most of them being associated with WC and SF. Moreover, 41 species (16.7%) were rare in the study area, with WC and SF harboring the highest number of these species. None of the forest planta-tions presented exclusive or rare species.

Figure 2: Species accumulation curve for the Lower Delta of the Parana River. Each sampling unit represents a published report (1-12) or a bird survey carried out for this study (13-14). See Table 1 for details. The mean and 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines) are shown based on 1000 random trials.

We identified 14 (5.7 % of the total) threatened species in the lower delta (Table 2 and 3, Fig. 3). Three of those species were threatened both at global and national levels, whereas the remaining 11 species are at risk of extinction at the national level. Species at high risk of extinction were not evenly distributed among vegetation types, with most of them occurring in FM and ERG (Table 3). Regarding the three globa-lly endangered species (BirdLife International 2021), Bay-capped Wren-Spinetail (Spartonoica maluroides) was recorded in FM and ERG, Hudson’s Canastero (As-thenes hudsoni) was only found in ERG, and Marsh See-deater (Sporophila palustris) was recorded in FM and BSASG. Some near threatened species were widely distributed in several landscape units and vegetation types, such as Dusky-legged Guan (Penelope obscura), Curve-billed Reedhaunter (Limnornis curvirostris) and Scarlet-headed Blackbird (Amblyramphus holosericeus).

Discussion

We studied the assemblages of birds in the Lower Paraná River Delta, and described the association of these birds with vegetation types. We found 253 bird species, which accounted for 24.4% of the bird spe-cies richness of Argentina (MAyDS and AA 2017). Ac-cording to these results, the study area harbors 57.7% of the bird species of Buenos Aires Province (343 spe-cies) (Darrieu et al. 2013) and 79% of the bird species of Entre Ríos Province (317 species) (Dardanelli et al. 2018). These results indicate that the lower delta can be a key area maintaining high bird diversity in the region. However, we mostly focused our study during the breeding season, which could have resulted in missing wintering species (e.g. Bar-winged Cinclodes Cinclodesfuscus). To our knowledge, we present one of the most complete checklists of the lower delta of the Paraná River.

The high landscape heterogeneity of the lower delta allows the coexistence of species with different ecological traits and habitat requirements. In this study, exclusive species of a single habitat type repre-sented 23.5% of the total. Most of these habitat-res-tricted species were associated with natural habitats like WC and SF, followed by ERG, FM and EF. Landsca-pes with forest plantations were the poorest in terms of exclusive species. Some examples of exclusive spe-cies are Great Grebe (Podiceps major), Fulvous Whist-ling Duck (Dendrocygna bicolor) and Amazon Kingfi-sher (Chloroceryle amazona) (aquatic obligate); Spotted Tinamou (Nothura maculosa) and Hudson’s Canastero (grasslands specialists); and Ultramarine Grosbeak (Cyanoloxia brissonii) (forests specialists). In addition, some rare species were found only in native vegeta-tion types, representing 16.7% of the species. These species are mostly grassland and wetland specialists (e.g., Aningha Anhinga anhinga, Red-and-white Crake Laterallus leucopyrrhus). A greater or balanced num-ber of studies by vegetation and unit type, would be necessary to adjust these values and analyze the im-portance and contribution of each habitat.

We recorded the Wedge-tailed Grass Finch (Em-berizoides herbicola)for the first time in Buenos Aires Province, in a grassland from a forest company. This indicates that biodiversity in the area is still not completely known, even being a region close to the most important urban center of Argentina. Our results show the importance of baseline data collec-tion to understand species distribution, even in lar-gely monitored areas.

The lower delta provides habitat for 14 species at high risk of extinction (Table 3), with most of them being registered in the natural habitats of ERG, FM, SF and BSASG. In our survey, we did not find Sa-ffron-cowled Blackbird (Xanthopsarflavus), a vulnerable species (BirdLife International 2021), that was last detected in the study area in the 1990s (Sica et al. 2018). In Argentina, due to fragmentation and degradation of wet grasslands caused by agricultu-ral use (Fraga et al. 1998), its populations are now restricted to southern Entre Rios, northern Corrientes and southern Misiones. The mainland area of the lower delta represents the southern limit of this species range (BirdLife International 2021), which appears to have contracted even further.

If the current land use tendency in the area con-tinues (i.e., expansion of afforestation, intensified silvopastoral and pastoral systems), and no biodi-versity conservation strategies are implemented at local and landscape levels (such as the biodiversi-ty protocol of conservation strategies in Salicaceae plantations of the Lower Delta of the Parana River; Fracassi et al. 2013), the consequences for bird po-pulations in the area could be dramatic. According toBó et al. (2002), more than 60% of the species in the delta are primarily associated with wetland habitats, such as freshwater marshes, watercourses and ripa-rian forests. Our results support this evidence, since we found that most of the species were recorded in natural wetlands. Only around 30% of the recorded species used the forest plantations as alternative habitats, and none of these species were exclusive, rare or under any category of threat. For instance, only 50 species were recorded in an adult poplar plantation, meaning that this habitat type may not be fulfilling the habitat requirements for most of the species that inhabit the Lower Delta.

Figure 3: Documented records of species at high risk of extinction in the Lower Delta of the Parana River: a) Long-winged Harrier (Circus buffoni) (Campana, November 11th, 2020), b) Stright-billed Reedhaunter (Limnoctites rectirostris) (Campana, Buenos Aires, October 10th, 2019), c) Curve-billed Reedhaunter (Limnornis curvirostris) (Campana, Buenos Aires, October 10th, 2019), d) Scar-let-headed Blackbird (Amblyramphus holosericeus) (Campana, November 11th, 2020). Photo: Cabanne GS.

For Straightbilled Reedhaunter (Limnoctites rec-tirostris) (Fig. 3B), which is vulnerable (AM) in Argentina (MAyDS and AA 2017), the delta encompassed the entire range of the species in Argentina. Thus, this is a key region for its conservation. We found it in degraded grasslands in Entre Ríos and Buenos Aires, as well as in FM. We suggest re-evaluating the conservation status of the species in the coun-try because it is highly likely that its conservation situation is worse than suggested by the literature (MAyDS and AA 2017). During the two surveys con-ducted in the breeding season of 2019 in Ceibas, we detected a total of three isolated individuals that were in two distant locations. These birds neither vocalized spontaneously nor responded to play-back consistently. They might have been indivi-duals without an established territory. Importantly, we did not find the species in Ibicuy and provincial route 45 (Entre Ríos), a region with records during the 2006-2010 period (e.g., eBird: S55185305 and S12301645). During our surveys in Entre Ríos, we noticed that the quality of the specific habitat of Straight-billed Reedhaunter (i.e., grasslands with Eryngiumpandanifolium, E. eburneum and E. horridum) was very degraded, which might explain our failure to find active territories in Entre Ríos Province. We only found a pair that actively defended stable territories in the insular part of the Lower Delta (Campana and San Fernando, Buenos Aires, landscape unit IVa). However, whether this population comprises a viable population is unknown, and there is no infor-mation about its survival after September 2020 fires (FIRMS 2020).

The Yellow Cardinal, whose distribution limit is in the study area, was not recorded in any of the systematic surveys in this work, although it was ob-served by the authors. Citizen science (e.g., eBird, Ecoregistros) would be a good complementary al-ternative to systematic surveys to increase detec-tion or records of uncommon species (Callaghan et al. 2018). However, survey effort is not declared by birdwatchers, and it is necessary to identify minimal standards of quality to use these data (Hochachka et al. 2012). Without such information, it is difficult to assess the demographic status of species. Using systematic survey data may guarantee the same pros-pecting effort; however, for rare species it requires specific survey methods (e.g., playback or live capture; Lor and Malecki 2002).

We found that the Lower Delta of the Paraná River is a refuge for high bird diversity in the Pampas and Espinal regions, two biomes that are heavily impacted by human activity. The Delta also harbors populations of species with high risk of extinction, such as Straigth-billed Reedhaunter and Marsh Seedeater. Therefore, urgent actions are needed to ensure the management and conservation of these wetlands.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the people that participated in the field surveys, especially Natalia Garcia, Andrea Goijamn, Carlos Sica, Evelyn Figueroa Schibber, Facundo Luque, Agustin Mezzabotta, Pedro Moreira, German Saigo, Fernanda Sansalone, Facundo González, Federico Bartalak, Jose Luis Cosentino, Silvia Rodriguez, Eduardo Wosekian, Bernardo Lartigau, Damian Voglino, Leandro Antoniazzi and Emilio de León. The companies Arauco Argentina, Ederra S.A., Caaby S.A., Papel Prensa and other landowners always provided their support and allowed us to use their facilities. We thank Prefectura Naval Argentina for the logistical support. We thank the National Par-ks Administration (APN) of Argentina. The studies were financially supported by several projects: PICT

uBio

uBio