Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos argentinos de pediatría

versión impresa ISSN 0325-0075versión On-line ISSN 1668-3501

Arch. argent. pediatr. vol.115 no.2 Buenos Aires abr. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2017.140

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2017.eng.140

Depressive symptoms and associated factors in caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit

Jorge L. Alvarado Socarrás, M.D.a b, Edna M. Gamboa-Delgado, M.D.c, Silvia Trujillo Cáceres, Nursed and Sandra Rodríguez Forero, Nursea

a. Neonatal Unit, Department of Pediatrics. Cardiovascular Foundation of Colombia.

b. Latin American Organization for Health Research Promotion.

c. Universidad Industrial de Santander.

d. Cardiovascular Foundation of Colombia.

E-mail address: Jorge Alvarado Socarrás, M.D.: Jorgealso2@yahoo.com

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

Received: 4-7-2016

Accepted: 10-19-2016

ABSTRACT

Introduction. A high prevalence of depressive symptoms has been reported in family members of newborn infants hospitalized in neonatal intensive care units. This causes a high negative impact on the newborn infant-family bond. Objective. To establish the prevalence of depressive symptoms and their associated factors in caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit in Colombia.

Materials and Methods. Cross-sectional, analytical study conducted at a tertiary care health facility specialized in cardiovascular disease. The Beck Depression Inventory-II was administered upon admission to the NICU and on Day 8. Depressive symptoms were considered present if caregivers had intermittent, moderate, severe, or extreme depression. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were done using binomial regression models.

Results. A total of 107 children and their caregivers were studied. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 20.56% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 12.77-28.34) at baseline and 12.86% (95% CI: 4.1-20.89) on Day 8. Male caregivers and caregivers older than 30 years old had a lower risk of having depressive symptoms whereas being the head of the household, having completed primary education or no education at all, and having a baby with an Apgar score at birth of 1-6 were risk factors for developing depressive symptoms.

Conclusions. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was high. Being the head of the household, having a low level of education, and an Apgar score at birth of 1-6 were associated with depressive symptoms among caregivers.

Key words: Depression; Caregivers;; Newborn infant; Neonatal intensive care units.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of postpartum depression ranges between 10% and 15%.1 Such rate and the negative impact it causes on the mother-child bond have originated the recommendation made by the American Academy of Pediatrics to look for postpartum depressive symptoms.2 These symptoms may be more relevant in conditions involving unexpected newborn infant (NBI) outcomes, such as the hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Depression has been observed in 28% to 67% of parents of infants hospitalized in the NICU.3 Prior studies have reported negative emotional reactions among caregivers in the case of hospitalization, including guilt, sadness, aggressiveness, anger, fear, anxiety, despair, a feeling of failure, and loss of self-esteem.4

Some studies have tried to identify factors associated with the presence of depressive symptoms. Certain characteristics related to the NBI (prematurity, clinical diagnosis, and others), the mother (age, level of education, socioeconomic level, and history of depression), and the hospital setting (stressful situations in the NICU, ambiguous medical information, distance from the place of residence) may contribute to the onset of depression.5-8

Advances have been made in the assessment of this clinical situation in developed countries. On the contrary, in developing countries, there is little information to establish the size of the problem so as to conduct timely interventions to improve the quality of health care and favor the bond among NBIs, mothers, and caregivers.9-12

Therefore, the objective of this study was to establish the prevalence of depressive symptoms and their

associated factors in family caregivers of NBIs hospitalized in a NICU in Colombia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between January and September 2015, a cross-sectional, analytical study was conducted in caregivers of NBIs hospitalized in the NICU of a tertiary care health facility specialized in cardiovascular disease.

Caregivers were defined as the mother, the father or any other family member in charge of taking care of hospitalized NBIs.

Inclusion criteria

We included NBIs admitted to the NICU and their caregivers (one per infant) who agreed to participate.

Caregivers and NBIs who were lost to the second assessment were excluded from the analysis.

Caregivers were contacted by a nurse trained in this project, who invited them to complete a survey on outcome measures of interest regarding NBIs and their caregivers.

Participants filled in the Beck Depression Inventory-II13 (BDI-II), which was administered one day after the NBI's admission and 8 days after the first measurement, as long as the NBI was still hospitalized.

The survey took an average of 15 minutes. The inventory was validated with a pilot test conducted in a group of participants similar to the study sample.

The dependent outcome measure corresponded to the presence of depressive symptoms, which was established with the administration of the BDI-II. This instrument was developed to establish the correspondence with the criteria proposed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) for the diagnosis of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II is made up of 21 items, with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 63 points14 (see Annex 1).

Categories are classified based on the total score as follows: normal ups and downs for a 0-10 score, mild mood disturbance for an 11-16 score, intermittent depression for a 17-20 score, moderate depression for a 21-30 score, severe depression for a 31-40 score, and extreme depression for a score over 41.

Depressive symptoms were considered present if caregivers experienced intermittent, moderate, severe, or extreme depression. In the case of having depressive symptoms, caregivers were assessed by the Department of Psychology.

The other two symptom categories were normal ups and downs, defined as symptoms that did not account for any type of danger, and mild mood disturbance, which corresponded to symptoms that possibly required follow-up with a psychotherapist should they transition to a depression status.14

Independent outcome measures were as follows:

a) For NBIs: sex, gestational age (GA), mode of delivery, weight, Apgar score at 1 min, prior hospitalizations, diagnoses, malformations, sepsis, adverse events, and length of stay (in days). The severity of the NBI condition was also analyzed using the Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology I-II (SNAP I-II).15

b) For caregivers: sex, age, marital status, number of children, place of residence, socioeconomic level, level of education, income, occupation, working hours, living with a partner, being the head of the household, history of depression, negative experience at the NICU (other hospitalized children and/or mortality of a child in the NICU).

In addition, the sources of stress were established using the parental stressor scale,16,17 which measured parental stress related to hospitalization in the NICU based on two types of score: 1) it allowed making a microanalysis of stress in three different areas, including physical and psychosocial aspects of the NICU, and 2) it was an overall score to classify the overall stress diagnosis among parents of NBIs hospitalized in the NICU into three levels: low, middle, and high. The independent outcome measures related to symptoms were as follows (see Annex 2):

- NBI appearance and behavior: weakness, pain, needles and tubes (feeding or breathing tubes), breathing patterns, changes in skin color, persistent crying, wrinkled appearance, very small size, and skin alterations.

- Parental role alteration: assessed based on situations such as being separated from the NBI, not being able to help or care for the NBI in this situation, not being able to share the NBI with other family members, being afraid to touch or hold the NBI, not feeling supported by family members, not being able to protect the NBI, not being able to stay close to the NBI due to visit cancellation, not being able to make the NBI feel he/she is not alone, and witnessing the death of a NBI during hospitalization.

- Sights and sounds of the NICU: seeing the NBI connected to a ventilator, seeing that the NBI does not cry like other babies, hearing monitor/equipment alarms, and seeing a large number of people working in the NICU.

A score of 1 to 5 was assigned to each of the aspects assessed in these three subscales to establish the level of parental stress. The maximum score assigned to the sources of stress related to NBI aspect and behavior was 60 points; to the parental role, 55 points; and to sights and sounds of the NICU, 20 points. The total maximum score any caregiver could reach on this scale was 135. The level of stress was categorized as low (1-45 points), moderate (46-90 points), and high (91-135 points).

A descriptive analysis was done, and categorical outcome measures were described as proportion and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the distribution of continuous outcome measures. These outcome measures were described as mean and standard deviation if they had a normal distribution. Otherwise, they were described as median and their corresponding minimum and maximum values. To establish if there were statistically significant differences,

Student's t test and Fisher's exact test were used for continuous and categorical outcome measures, respectively. Bivariate analyses were done to compare the outcome measure of interest (presence of depressive symptoms among caregivers) and each independent outcome measure. Outcome measures with a p value < 0.20 in this analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. A backward multivariate analysis was done using binomial regression models to estimate prevalence ratios (PRs).

This study was conducted in accordance with the regulations for health research valid in Colombia,18 and was approved by a research ethics committee. All participants signed an informed consent form.

RESULTS

Newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

A total of 107 NBIs were included (number of caregivers at study initiation: 107; number of caregivers at follow-up assessment: 70) (Figure 1). Seven NBIs died. The median (range) age at the time of admission to the NICU was 3 days old (1-52 days old). Preterm NBIs (GA < 37 weeks) accounted for 59.8% of all NBIs included in the study; term NBIs (GA of 38-40 weeks), for 38.3%; and postterm NBIs (GA > 41 weeks), for 1.9%. Other sociodemographic outcome measures are described in Table 1. The sources of parental stress are described in Annex 2.

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants

Table 1. Description of the general characteristics of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (n= 107) and their caregivers (n= 107)

Respiratory alterations was the most common (75.5%) diagnosis at the time of admission. Other diagnoses included congenital heart disease, metabolic alterations, sepsis, central nervous system, gastrointestinal system, genitourinary tract, and genetic alterations.

The median (range) total length of stay of NBIs was 29 days (2-113 days), which included hospitalization in other departments of the hospital different from the NICU. Table 2 describes the severity of the conditions of NBIs hospitalized in the NICU.

Table 2. Severity of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit. Results of the Score for Neonatal Acute

Physiology I-II (n= 107)

Caregivers

Women accounted for 73.8% of caregivers; the median (range) age was 29 years old (15-56 years old). The mother was the prevalent caregiver of hospitalized NBIs (59.8%), followed by the father (26.1%), and another caregiver (14%). The most common marital status of caregivers was domestic partnership (66.3%), followed by married (23.3%). The main occupation was housewife (35.5%), and the median (range) working hours per day was 8 hours/day (0-18 hours/day). Of all surveyed caregivers, 43.9% were the head of the household. In addition, 15.9% had had another child hospitalized in the NICU, and 4.6% had a history of child mortality.

Sources of stress among caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

The median (range) total score was 28 points (12-50 points) in the NBI appearance and behavior subscale, 24 points (11-42 points) in the parental role alteration subscale, and 11 points (4-20 points) in the sights and sounds of the NICU subscale. The mean total score for parental stress was 65 points, with a 19.8 point standard deviation. The level of parental stress was moderate in 65.2% of caregivers, low in 20.2%, and high in 14.5%.

Depression-related aspects among caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

Of all caregivers, 4.7% (n = 5) indicated to have been diagnosed with depression, and two had received treatment. However, considering only the mothers of studied NBIs, 20.3% (n = 13) had been diagnosed with depression during gestation, and 26.6% (n = 17) had postpartum depression.

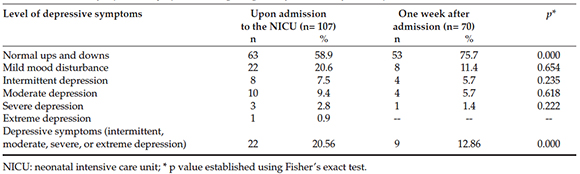

In relation to the prevalence of depressive symptoms, the baseline measurement showed that 58.9% of caregivers had normal ups and downs, and 20.6% had a mild mood disturbance. According to the final measurement, 84.1% of caregivers had normal ups and downs, and 7.5% a mild mood disturbance. The follow-up measurement showed a higher prevalence of normal ups and downs compared to the baseline measurement (75.7% versus 58.9%, p = 0.000) (Table 3).

Table 3. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 20.6% (95% CI: 12.7-28.3) at baseline and 12.9% (95% CI: 4.1-20.9) at follow-up. Statistically significant differences were observed between the prevalence of depression at baseline and at followup (p = 0.000). Also, 28% of caregivers received psychotherapy.

Factors associated with the severity of depressive symptoms among caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

The multivariate analysis showed that sociodemographic and clinical outcome measures were significantly associated with depressive symptoms among caregivers of hospitalized NBIs. Male caregivers and caregivers older than 30 years old had a lower risk for depressive symptoms whereas being the head of the household, having a low level of education, and a low Apgar score at 1 minute (1-6) were risk factors for depressive symptoms (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with depressive symptoms among caregivers of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

DISCUSSION

In this study, the prevalence of depressive symptoms among caregivers of NBIs hospitalized in the NICU was higher at baseline than at followup. In our population, the factors associated with this event included being the head of the household, having a low level of education, and a low Apgar score at 1 minute.

In relation to the overall score in the parental stressor scale, more than half of caregivers (65.2%) had a moderate level of stress. Based on the subscale analysis, the sights and sounds of the NICU subscale accounted for the highest stressor.

In relation to the prevalence of depressive symptoms among caregivers of NBIs hospitalized in the NICU, prior studies reported a 10-59% prevalence.1'6'7'91219 In our population, the prevalence was close to the lower limit of this range in both measurements.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms varies and is multifactorial. However, intervention programs may reduce symptoms of depression and stress among caregivers during hospitalization.20

Studies on the determination of factors associated with depressive symptoms are limited, they have been conducted in developed countries, and have mainly assessed NBIs' mothers.

Based on those studies, factors associated with depressive symptoms include the level of stress, an inadequate family role, poor social support, being single/living alone, lack of cultural identity, being an immigrant, being female, being a woman younger than 35 years old, a prior psychiatric disease diagnosis, and the presence of posttraumatic stress and anxiety.710-1221 The association with age is consistent with our results.

In addition, other studies failed to establish a relationship with the level of education, employment status, number of children, history of depression, gestational disease, level of parental stress, not living with the father of the baby, and NBI-related outcome measures, such as the severity of disease, GA, sex, and single versus multiple pregnancy.710-12 Prior results differ from our study because, in our population, a low level of education, being the head of the household, and a low Apgar score were associated with the presence of depressive symptoms.

The level of parental stress was moderate in our population, which is similar to what has been reported in a multicenter study conducted at the NICUs participating in the Neocosur network22 among the parents of NBIs with a very low birth weight. In turn, these results are different from those pointed out by Ruiz et al.,20 whose study found that most mothers in the control group had an extreme stress level whereas those in the intervention group showed a moderate stress level.

When considering stress levels as per stress subscales, a higher score was observed in the sights and sounds of the NICU subscale, followed by an equal score in both the NBI appearance and behavior and the parental role alteration subscales. This contrasts the findings of other studies, which found that a higher level of stress is observed in the parental role alteration subscale because of parents' inability to meet their babies' basic needs and the fact that they are separated, followed by the NBI appearance and behavior subscale and, in the last place, the sights and sounds of the NICU subscale.20,23-26

Some limitations were taken into consideration for the interpretation of our findings. First of all, this is a cross-sectional study, which hinders the possibility of making inferences on the event's transient nature. Second of all, the reduced sample size at follow-up may have compromised the final measurement of depressive symptoms. In addition, this study did not include the measurement of some outcome measures previously studied by other authors, such as NBI cortisol levels, and caregiver resilience.27-29

Otherwise, some of the strengths of this study were that it allowed caregivers to self-complete the depressive symptom report scales, and the inclusion of a structured survey to explore outcome measures of interest. In addition, the detection of factors associated with depressive symptoms in the population of developing countries is actually useful to improve the interdisciplinary management.

To sum up, the prevalence of depressive symptoms among caregivers of NBIs hospitalized in a NICU in Colombia was noteworthy, and was associated with clinical and social factors. For this reason, it is critical to provide psychosocial assessment to the caregivers of hospitalized NBIs to improve the quality of health care provided to NBIs, and provide comprehensive care. In this regard, this type of studies identifies the onset of depressive symptoms in caregivers of NBIs hospitalized in the NICU, forcing to consider caregivers as a new focus of intervention which has been undervalued in the past.

Further cohort studies should be conducted to explore the time of onset and waning of depressive symptoms during NBIs' stay in the NICU and upon discharge from the NICU, given that they have been reported to appear up to two years after discharge.28,30

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of depressive symptoms was high. Being the head of the household, having a low level of education, and an Apgar score at birth of 1-6 were associated with depressive symptoms among caregivers.

ANNEX 1

ANNEX 2

Assessment of parental stress among caregivers

of newborn infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit

1. Toohey J. Depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012;55(3):788-97. [ Links ]

2. Paul I, Downs D, Schaefer E, Beiler J, et al. Postpartum anxiety and maternal-infant health outcomes. Pediatrics 2013;131(4):e1218-24. [ Links ]

3. Segre LS, McCabe JE, Chuffo-Siewert R, O'Hara MW. Depression and Anxiety symptoms in mothers of newborns hospitalized on the neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Res 2014;63(5):320-32. [ Links ]

4. Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D. Parenting the prematurely born child: pathways of influence. Semin Perinatol 1987;21(3):254-66. [ Links ]

5. Busse M, Stromgren K, Thorngate L, Thomas KA. Parents' responses to stress in the neonatal intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse 2013;33(4):52-9. [ Links ]

6. Alkozei A, McMahon E, Lahav A. Stress levels and depressive symptoms in NICU mothers in the early postpartum period. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27(17):1738-43. [ Links ]

7. Helle N, Barkmann C, Bartz-Seel J, Diehl T, et al. Very low birth-weight as a risk factor for postpartum depression four to six weeks postbirth in mothers and fathers: Crosssectional results from a controlled multicentre cohort study. J Affect Disord 2015;180:154-61. [ Links ]

8. Helle N, Barkmann C, Ehrhardt S, von der Wense, A et al. Postpartum anxiety and adjustment disorders in parents of infants with very low birth weight: Cross-sectional results from a controlled multicentre cohort study. J Affect Disord 2016;194:128-34. [ Links ]

9. Montirosso R, Fedeli C, Del Prete A, Calciolari G, et al. Maternal stress and depressive symptoms associated with quality of developmental care in 25 Italian Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A cross sectional observational study. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51(7):994-1002. [ Links ]

10. Garfield L, Holditch-Davis D, Carter CS, McFarlin BL, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in low-income women with very low-birth-weight infants. Adv Neonatal Care 2015;15(1):e3-8. [ Links ]

11. Gonülal D, Yalaz M, Altun-koro lu O, Kültürsay N. Both parents of neonatal intensive care unit patients are at risk of depression. Turk J Pediatr 2014;56(2):171-6. [ Links ]

12. Ballantyne M, Benzies KM, Trute B. Depressive symptoms among immigrant and Canadian born mothers of preterm infants at neonatal intensive care discharge: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13(Suppl 1):S11. [ Links ]

13. Beck A, Brown G, Steer R. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [ Links ]

14. Sanz J, Vásquez C. Fiabilidad, validez y datos normativos del inventario para depresión de Beck. Psicothema 1998;10(2):303-18. [ Links ]

15. Helal NF, Samra NM, Abdel Ghamy E, Said E. Can the Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology II (SNAPII) Predict Morbidity and Mortality in Neonates with Sepsis? J Neonatal Biol 2013;2(2):121. [ Links ]

16. Miles MS, Funk SG, Carlson J. Parental Stressor Scale: neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Res 1993;42(3):148-52. [ Links ]

17. Caruso A, Mikulic IM. El estrés en padres de bebés prematuros internados en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos Neonatales: traducción y adaptación de la escala Parental Stressor Scale: Neonatal intensive care unit (PSS: NICU -M.S. Miles y D. Holditch Davis, 1987; M.S. Miles y S.G. Funk, 1998). Anu Investig [online] 2012;19(2):19-26.

18. República de Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. Resolución No. 008430 de 1993. Colombia; 4 de octubre de1993. [Acceso: 20 de octubre de 2016]. Disponible en: https://www.unisabana.edu.co/fileadmin/Documentos/Investigacion/comite_de_ etica/Res_8430_1993_-_Salud.pdf.

19. Shaw RJ, Lilo E, Storfer-isser A, Ball MB, et al. Screening for symptoms of postpartum traumatic stress in a sample of mothers with preterm infants. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2014;35(3):198-207. [ Links ]

20. Ruiz A, Ceriani Cernadas JM, Cravedi V, Rodríguez D. Estrés y depresión en madres de prematuros: un programa de intervención. Arch Argent Pediatr 2005;103(1):36-45. [ Links ]

21. Kong L, Cui Y, Qiu Y, Han S, et al. Anxiety and depression in parents of sick neonates: a hospital-based study. J Clin Nurs 2013;22(7-8):1163-72. [ Links ]

22. Wormald F, Tapia JL, Torres G, Cánepa P, et al. Estrés en padres de recién nacidos prematuros de muy bajo peso hospitalizados en unidades de cuidados intensivos neonatales. Estudio multicéntrico. Arch Argent Pediatr 2015;113(4):303-9. [ Links ]

23. Montirosso R, Provenzi L, Calciolari G, Borgatti R. Measuring maternal stress perceived support in 25 Italian NICUs. Acta Paediatr 2012;101(2):136-42. [ Links ]

24. Gonzalez MA. Stress, depresión y ansiedad madres de los recién nacidos internados en UCIN. 1° Congreso Argentino de Neonatología; 29 de Sept - 2 de Oct de 2010; Buenos Aires: Sociedad Argentina de Pediatría; 2010. [Acceso: 30 de agosto de 2016]. Disponible en: http://www.sap.org.ar/docs/congresos/2010/neo/gonzalezstress.pdf.

25. Miles MS, Funk SG, Kasper MA. The stress response of mothers and fathers of preterm infants. Res Nurs Health 1992;15(4):261-9. [ Links ]

26. Chourasia N, Surianarayanan P, Bethou A, Bhat V. Stressors of NICU mothers and the effect of counseling-experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital, India. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26(6):616-8. [ Links ]

27. Bugental D, Beaulieu D, Schwartz A. Hormonal sensitivity of preterm versus full-term infants to the effects of maternal depression. Infant Behav Dev 2008;31(1):51-61. [ Links ]

28. Rogers C, Kidokoro H, Wallendorf M, Inder T. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J Perinatol 2013;33(3):171-6. [ Links ]

29. Escartí A, Boronat N, Llopis R, Torres R, Vento M. Estudio piloto sobre el estrés y la resiliencia familiar en recién nacidos prematuros. An Pediatr 2016;84(1):3-9. [ Links ]

30. Miles M, Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz T, Scher M. Depressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007;28(1):36-44. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en