Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos argentinos de pediatría

versión impresa ISSN 0325-0075versión On-line ISSN 1668-3501

Arch. argent. pediatr. vol.116 no.4 Buenos Aires ago. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2018.e529

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2018.e529

Impact of a health care quality improvement intervention to prevent pressure ulcers in a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

Valeria Aprea, M.D.a, Facundo Jorro Barón, M.D.a, Claudia Meregalli, M.D.a and María Carolina Sabatini, M.D.a

a. Department of Intensive Care of Hospital de Niños "Dr. Pedro de Elizalde" (HGNPE), Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

E-mail address: Facundo Jorro Barón, M.D.: jorrobox@yahoo.com.ar

Funding: None

Conflict of interest: None.

Received: 9-11-2017

Accepted: 2-8-2018

ABSTRACT

Introduction. Among children hospitalized in the intensive care unit who have pressure ulcers (PUs), more than 50% are related to the sustained pressure from a device or equipment. PUs are an indirect indicator of the quality of health care.

Objective. To assess the impact of a health care quality improvement intervention on the development of PUs at the pediatric intensive care unit.

Materials and methods. Uncontrolled, before and after study. Pre-intervention: measurement of PUs; post-intervention: implementation of a bundle of measures (staff training, identification of patients at risk, and pressure relief by using antibedsore mattresses and polymer gel positioners) and the same measurements.

Results. A total of 152 patients were included: 74 before the intervention and 78 after the intervention. A significant reduction was observed in the incidence of PUs (preintervention: 50.60%; post-intervention: 23.08%; p= 0.001). A higher risk score was seen in the post-intervention group (pre-intervention: 12.4 ± 1.9; post-intervention: 13.7 ± 2.1; p= 0.001). No differences were observed in the risk score on the day of PU onset and the number of PUs. The risk-stratified analysis maintained the significant difference in the incidence of PUs (PIM2 < 5: 47.37%; 19.23%; p= 0.004; and PIM2 > 5: 55.56%; 30.77%; p= 0.053).

Conclusion. A lower incidence of PUs was observed after the implementation of the health care quality improvement intervention. No changes were detected in the number of PUs or the severity staging.

Key words: Program assessment; Pressure ulcers; Quality improvement; Pediatrics.

INTRODUCTION

The skin is the largest tissue of the human body and works as a protective barrier against bacteria and physical and chemical substances while maintaining a stable internal environment (homeostasis). The skin receives one third of the circulating blood volume and is involved in several functions, including protection, immunity, temperature regulation, metabolism, communication, identification, and senses.

An injury that extends through the epidermis and dermis may lead to systemic infections, increased morbidity, higher health care costs, and negative psychosocial implications associated with ulcers and alopecia. These ulcers are areas of focal necrosis of the skin and underlying tissue, caused by the interruption of blood flow to the affected area, as a consequence of prolonged pressure between a bony prominence and the external surface.1,2

The development of pressure ulcers (PUs) has been widely studied in children and adults, and has been described as typically occurring in adult patients. However, several risk factors have been described for the potential development of PUs in pediatric patients that are different from those observed in adult patients.3

The neonatal and pediatric population admitted to the critical care unit and children with chronic conditions, psychomotor deficits, neurological disorders or spinal cord injuries are the groups at higher risk and with a higher incidence of PUs. In critically-ill patients, the incidence of PUs has been reported to range from 18% to 27%.4

In this population of patients, the development of PUs has been related to different clinical situations.5-8

PUs are an indirect indicator of health care quality and account for an increasing health problem because they affect the patient's quality of life, extend the length of stay in the hospital, increase mortality, and imply a high cost on the health system.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to assess the impact of a health care quality improvement intervention on the development of PUs at the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

MATERIALS AND METHODS Design

Uncontrolled, before and after study.

The study was carried out in two phases. During the first phase ("before"), from March to September 2014, baseline data were analyzed. Based on analyzed data, prevention measures were proposed. As of April 2016, a health care improvement intervention was implemented to reduce the incidence of PUs at the PICU (implemented bundle of measures: see Annex 1). During the second phase ("after"), from May to September 2016, the intervention continued and its results on PU incidence were measured.

Upon admission, all children were assessed for the risk of PU using the Braden Q scale and subjected to a comprehensive examination of the skin, including a thorough examination of the areas at a higher risk, such as under braces or orthoses, tracheostomy tubes, etc.; results were documented in a data collection record.

This procedure was repeated on a daily basis; if any ulcer was observed, the location, size, and stage were recorded.

Description of the study setting

The study was carried out at the PICU of Hospital General de Niños Pedro de Elizalde (HGNPE). This unit has 11 medical surgical beds, with no cardiovascular surgery.

Sample

All children older than 1 month admitted to the PICU of HGNPE during the period between March and September 2014 and the period between May and September 2016.

Exclusion criteria:

• Length of stay in the PICU of less than 48 hours.

• Presence of ulcers at the time of admission.

Data collection instrument

The data collection record consisted of 3 parts (see Annex 2):

• Epidemiological data.

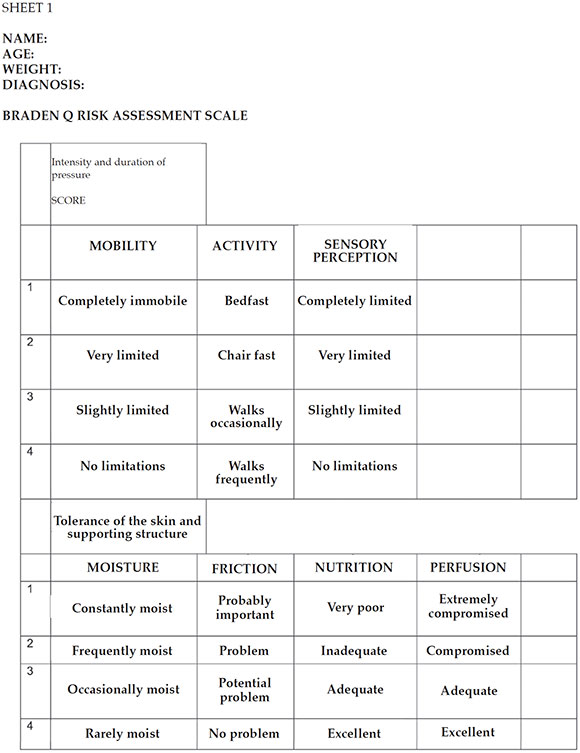

• Assessment of the risk for PUs: the Braden Q scale9 was administered at the time of admission of the child to the PICU and on a daily basis (see Annex 3).

• PU staging: the 4-stage system from the National Advisory Group for the Study of Pressure Ulcers and Chronic Wounds (Grupo Nacional para el Estudio y Asesoramiento en Úlceras por Presión y Heridas Crónicas, GNEAUPP)5 was used (see Annex 4).

Statistical analysis

Data were described as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on distribution. Before and after data were compared using Student's t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on normality and the χ2 test. Data were analyzed with the STATA 10.1 software (Statistics/Data Analysis Stata Corporation 4905 Lakeway Drive College Station, TX, USA).

Sample size

Eighty patients were estimated per phase to identify a minimum 20% difference between groups (baseline incidence of 40% versus final incidence below 20%), with a power over 80%, a p value < 0.05, and a 15% lost-to-follow-up.

Ethical considerations

In this study, patients were not identified by name or medical record number; they were coded. PU care and prevention has been a standard of care at the PICU as of May 2016. Based on this, we considered that it was not necessary to obtain an informed consent.

RESULTS

A total of 152 patients were included in the study; 74 in the pre-intervention period and 78 in the post-intervention period. Patients' median age was 7 months (IQR: 4.7-27.5). The median Pediatric Index of Mortality 2 (PIM2) score was 3.71 (IQR: 1.29-8.18). The median number of days of assisted mechanical ventilation (AMV) was 7 (IQR: 4-7) and the median length of stay in the PICU was 8 days (IQR: 6-14). No significant differences were observed in terms of age, weight, days of AMV, length of stay in the hospital, and diagnosis at the time of admission or between the pre-intervention and post-intervention groups. A higher severity score -PIM2- was observed in the pre-intervention group (4.88 [1.36-10.7]; 2.35 [1.196.18]; p= 0.012) (Table 1).

Table 1. Composition of patient groups before and after the intervention

The most common PU location was the lower occipital region, followed by the lateral malleolar and the upper occipital regions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Anatomic distribution of pressure ulcers

After the intervention period, a significant reduction was observed in the incidence of PUs (pre-intervention: 50.60%; post-intervention: 23.08%; p= 0.001). In the pre-intervention group, 81.9 PUs were observed over 1000 days of hospitalization; 1 corresponded to stage III; 7, to stage II; and 70, to stage I; whereas in the postintervention group, 29.3 PUs were observed over 1000 days of hospitalization; none corresponded to stage III; 2, to stage II; and 26, to stage I (Figure 2). The risk score for PUs at baseline was higher in the post-intervention group (preintervention: 12.4 ± 1.9; post-intervention: 13.7 ± 2.1; p= 0,001); no changes were observed in the risk score on the day of PU onset between both groups (pre-intervention: 13.1 ± 1.9; postintervention: 13.3 ± 1.4; p= 0.754). The number of PUs per patient was similar in both groups (Table 2).

Figure 2. Number and stage of pressure ulcers by period

Table 2: Intervention results among patient groups

A higher PIM2 score was recorded for the pre-intervention group, so a risk-stratified analysis was conducted. The PIM2 score was dichotomized into > 5 and < 5. After the stratification, a significant difference was still observed in the incidence of PUs (PIM2 < 5: 47.37%, 19.23%; p= 0.004; and PIM2 > 5: 55.56%, 30.77%; p= 0.053).

DISCUSSION

PUs are common adverse events in association with the care of hospitalized patients which, many times, can be prevented. At present, PUs are indicators of health care quality in critically-ill patients. According to the reports, the incidence of PUs in the pediatric population ranges from 10.2% to 33%.7,10-13 The incidence observed at the PICU of HGNPE in the first phase of the study was higher than that reported by other authors. However, once the analysis was discriminated by stage, it was observed that some studies did not include stage I PUs. In our series, only 1 stage III PU was recorded in the pre-intervention period and none in the post-intervention period.14 The National Quality Forum considers that stage III, IV, and unstageable PUs developed after admission are a preventable serious adverse event.14

The risk factors associated with the development of PUs in critically-ill children include use of AMV, length of stay in the PICU for more than 4 days, need for inotropic support, cardiorespiratory arrest after a cardiovascular surgery, use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), immobility, nutritional deficiency, and prolonged exposure to hospital devices or invasive catheters and tubes (noninvasive ventilation masks, tracheostomy tubes, etc.).5,6,11,15 A large number of PUs (50-60%) in the pediatric population are associated with hospital devices.3,16,17

The most common PU location in our study was in the lower occipital region, followed by the lateral malleolar and the upper occipital regions. This is consistent with the bibliography reports in children younger than 3 years.18

In our hospital, a bundle of measures was implemented to reduce the incidence of PUs, which included staff training, identification of patients at risk, and pressure relief by using antibedsore mattresses and polymer gel positioners. After the implementation, PU incidence reduced significantly in the postintervention period, which is consistent with the bibliography.3 No significant differences were observed between the pre-intervention and the post-intervention groups in terms of age, weight, diagnosis at the time of admission, days of AMV or length of stay in the hospital. The only difference between the groups was in relation to the PIM2 score, which was higher in the pre-intervention group; for this reason, a risk-stratified analysis was done. The PIM2 score was dichotomized into > 5 and < 5. After the stratification, a significant difference was still observed in the incidence of PUs.

The implementation of continuous quality improvement programs, including staff training, better communication, identification of patients at a higher risk for PUs, and the standardization of health care and management procedures, has shown to reduce PU incidence.3,12,15,16,19

In the field of pediatrics, few studies have been published on the implementation of a bundle of measures aimed at decreasing PU incidence. These include the study by Visscher et al.,3 who reported a 50% reduction in the incidence of PUs (pre-intervention: 14.3 x 1000 patient-days; post-intervention: 3.7 x 1000 patient-days, p < 0.05) after the implementation of a quality improvement program that included frequent skin assessments and staff training and empowerment. The authors implemented the same program at the neonatal intensive care unit, where it failed to reduce the incidence of PUs, which was explained as a result of introducing a new blood oxygen saturation model in the unit during the same measurement period.

Another study was conducted by Schindler et al.,15 who reported a reduction in the PU incidence at a PICU in the USA, from 18.8% to 6.8%, after the implementation of a quality improvement program that included staff training, frequent position changes and support surface inspection, and adequate nutrition.

Boesch et al.16 designed a strategy to reduce the incidence of PUs associated with tracheostomy tubes. The strategy consisted in frequent assessment of the skin and device, reduction of surface moist, and preventing device pressure on the skin. The implementation of the bundle of measures reduced the incidence of PUs (preintervention: 8.6%; during the intervention: 2.6%; post-intervention: 0.3%).

Among adults, the studies on quality improvement projects to reduce PU incidence have also reported successful results.1218

After the implementation of the improvement program, no changes were observed in the rate of higher stage PUs at our unit. This is different from what Tayyib et al.12 reported in two intensive care units (ICUs) from Arabia, who reported a reduction in the higher stage PUs in the postintervention period.

In our study, no significant differences were observed in the day of ulcer onset in both study phases or in the number of ulcers per patient. Coyer et al.19 reported, in an ICU from Australia, a lower number of PUs per patient and a later PU development during the length of stay in the ICU.

The limitations of this study are, first of all, that this study was carried out at a single site. Second of all, it should not be ruled out that the change in the staff's behavior during the second part of the research was due to their awareness of being actively observed (Hawthorne effect). In the third place, there is no certainty that results are associated with the implemented intervention, given the lack of a control group. In the fourth place, the study periods did not match accurately, although both corresponded to the winter months. Fifthly, although the intervention was fully implemented, the adherence to the bundle of measures was not estimated. Finally, the study does not assess the persistence of the benefit observed in the study over time.

CONCLUSION

A reduction in the development of PUs was observed at the PICU of HGNPE after the implementation of a health care improvement intervention. No changes were detected in the number of PUs or the severity staging. Very few PUs corresponded to stage III or higher.

ANNEX 1: BUNDLE OF MEASURES FOR IMPLEMENTATION

1. TRAINING PROGRAM: 30-minute sessions; participants: all physicians, nurses, and physical

therapists working at the department.

It included information on the following:

• PU etiology and risk factors.

• Use of assessment tools, such as the Braden Q scale, to predict the risk for PUs.

• Use of risk assessment categories to establish specific risks and warrant an effective health care

planning.

• Skin assessment.

• PU staging.

• Selection and/or use of support surfaces.

• Development and implementation of an individualized skin care program.

• Demonstration of transfer and position changes to reduce the risk for tissue damage.

• Instructions on the accurate documentation of relevant data.

• Roles and responsibilities of health care team members in relation to the assessment and prevention

of PUs.

• Skin care.

- Skin care:

• The status of the skin should be examined at least once a day.

• The patient’s skin should be maintained dry and clean at all times.

• pH neutral soaps or low-irritating cleansing products should be used.

• The skin should be cleaned with warm water, rinsed, and dried carefully without rubbing.

• No alcohol (cologne, etc.) should be used on the skin.

• Bony prominences should not be massaged directly.

• The areas where previous pressure injuries occurred should be closely assessed because these are at

a high risk for new injuries.

• Moist, diapers, drains, and vascular accesses should be supervised.

• Pressure should be controlled using the following principles: mobilization, position changes, special

support surfaces, and local protection against pressure.

• Position should be changed every 2 hours, avoiding shear and friction.

• Pressure on risky areas should be redistributed: occipital bone, sacrum, ears, heels, nose, etc.

• Linen should be changed daily and as necessary to keep it dry and crease-free.

• The location of monitoring devices should be modified.

2. PRESSURE RELIEF: Using special surfaces to manage pressure; antibedsore mattresses and polymer

gel positioners were acquired.

Details of new materials:

• 2 antibedsore air mattresses with adjustable pump, 190 x 80 x 6 cm.

• 12 mini heel positioners, 15 x 8.3 x 4.5 cm.

• 2 donut pillows for pediatric patients, external diameter 14 cm x internal diameter 5.7 cm x height 3.2

cm.

• 2 horseshoe cushions for pediatric patients, external diameter 14 cm x internal diameter 7.5 cm x

height 3.2 cm.

• 2 hip/shoulder blade pads, 50.8 x 50.8 x 1.3 cm.

3. ASSESSMENT OF RISK FOR PUs: The Braden Q scale was introduced for daily use. The purpose of

the Braden Q scale was to:

• Identify patients at risk for PUs in an early manner.

• Provide an objective criterion for the implementation of preventive measures based on the risk.

• Ensure the effective and efficient allocation of scarce preventive resources.

ANNEX 2. DATA COLLECTION RECORD

ANNEX 3: BRADEN SCALE

SCORE: 16-23, at risk; 13-15, moderate risk; 10-12, high risk; < 9, very high risk. (The Braden Q scale was developed to identify the

risk for pressure ulcers in children aged 21 days to 8 years old. It contains the 6 original sub-scales from the Braden scale for adults

and a seventh sub-scale for tissue oxygenation and perfusion. The cut-off point to determine patients at risk is a score of 16.)

ANNEX 4: PRESSURE ULCER STAGING SYSTEM*

National Advisory Group for the Study of Pressure Ulcers and Chronic Wounds (Grupo Nacional para el Estudio y Asesoramiento en Úlceras por Presión y Heridas Crónicas, GNEAUPP). Pressure ulcer staging system.

STAGE I

An observable pressure-related alteration of intact skin manifested as a non-blanchable erythema of the skin; in darker skin tones, the ulcer may appear with persistent red, blue, or purple hues. Compared to an adjacent or opposite area on the body not subjected to pressure, it may include changes in one or more of the following parameters:

- Skin temperature (warmth or coolness)

- Tissue consistency (edema, induration)

- And/or sensation (pain, itching)

STAGE II

• Partial thickness skin loss involving the epidermis and/or dermis.

• The ulcer is superficial and presents clinically as an abrasion, blister, or shallow crater.

STAGE III

• Full thickness skin loss involving damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, underlying fascia.

STAGE IV

• Full thickness skin loss with extensive destruction; tissue necrosis; or damage to muscle, bone, or

supporting structure (such as tendon, joint capsule, etc.).

• In this stage, as in stage III, injuries may occur with caverns, tunneling or sinuous paths.

In all cases, necrotic tissue should be removed before determining ulcer stage, if applicable.

* Pictures taken for teaching purposes as authorized by the National Advisory Group for the Study of Pressure Ulcers and Chronic Wounds (Grupo Nacional para el Estudio y Asesoramiento en Úlceras por Presión y Heridas Crónicas, GNEAUPP) Classification-Staging of Pressure Ulcers. Logroño. 2003. hup1/gneaupp.lnrolsecclonlbanco-de·lmaga.,osl.

1. Hagelgans NA. Pediatric skin care issues for the home care nurse. Pediatr Nurs 1993;19(5):499-507. [ Links ]

2. McLane KM, Bookout K, McCord S, et al. The 2003 national pediatric pressure ulcer and skin breakdown prevalence study: a multisite study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2004;31(4):168-78. [ Links ]

3. Visscher M, King A, Nie AM, et al. A Quality-Improvement Collaborative Project to Reduce Pressure Ulcers in PICUs. Pediatrics 2013;131(6):e1950-60. [ Links ]

4. Curley MA, Quigley SM, Lin M. Pressure ulcers in pediatric intensive care: incidence and associated factors. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2003;4(3):284-90. [ Links ]

5. Grupo Nacional para el Estudio y Asesoramiento en Úlceras por Presión y Heridas Crónicas. Clasificación-Estadiaje de las Úlceras por Presión. Logroño: GNEAUPP; 2003. [ Links ]

6. Neidig JR, Kleiber C, Oppliger RA. Risk factors associated with pressure ulcers in the pediatric patient following open-heart surgery. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs 1989;4(3):99-106. [ Links ]

7. Schindler CA, Mikhailov TA, Fischer K, et al. Skin integrity in critically ill and injured children. Am J Crit Care 2007;16(6):568-74. [ Links ]

8. McCord S, McElvain V, Sachdeva R, et al. Risk factors associated with pressure ulcers in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2004;31(4):179-83. [ Links ]

9. Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, García-Fernández FP, Soldevilla-Ágreda JJ, et al. Escalas e instrumentos de valoración del riesgo de desarrollar úlceras por presión. Logroño: GNEAUPP; 2009. [ Links ]

10. Groeneveld A, Anderson M, Allen S, et al. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in a tertiary care pediatric and adult hospital. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2004;31(3):108-20. [ Links ]

11. Schlüer AB, Schols JM, Halfens RJ. Risk and associated factors of pressure ulcers in hospitalized children over 1 yeard age. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2014;19(1): 80-9. [ Links ]

12. Tayyib N, Coyer F, Lewis P. A two-arm cluster randomized control trial to determine the effectiveness of a pressure ulcer prevention Bundle for criticaly ill patients. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015;47(3):237-47. [ Links ]

13. Frank G, Walsh KE, Wooton S, et al. Impact of a Pressure Injury Prevention Bundle in the Solutions for Patient Safety Network. Pediatr Qual Saf 2017;(22):e013. [ Links ]

14. National Quality Forum. Serious Reportable Events in Healthcare - 2011 Update: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC:NQF; 2011. [ Links ]

15. Schindler CA, Mikhailov TA, Cashin SE, et al. Under pressure: preventing pressure ulcers in critically ill infants. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2013;18(4):329-41. [ Links ]

16. Boesch RP, Myers C, Garrett T, et al. Prevention of tracheostomy-related pressure ulcers in children. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):e792-7. [ Links ]

17. Visscher MO, White CC, Jones JN, et al. Face masks for noninvasive ventilation: fit, excess skin hydration, and pressure ulcers. Respir Care 2015;60(11):1536-47. [ Links ]

18. Manning MJ, Gauvreau K, Curley MA. Factors associeted with occipital pressure ulcers in hospitalized infants and children. Am J Crit Care 2015;24(4):342-8. [ Links ]

19. Coyer F, Gardner A, Doubrovsky A, et al. Reducing pressure injuries in critically ill patients by using a patient skin integrity Care Bundle (INSPIRE). Am J Crit Care 2015;24(3):199-209. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en