Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Archivos argentinos de pediatría

versão impressa ISSN 0325-0075versão On-line ISSN 1668-3501

Arch. argent. pediatr. vol.117 no.3 Buenos Aires jun. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2019.149

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2019.eng.149

Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ-SAS): Analysis of psychometric properties

Selene Valero-Moreno, B.S. in Psychologya, Silvia Castillo-Corullón, M.D.b, Prof. Vicente Javier Prado-Gascó, M.D.c, Prof. Marián Pérez-Marín, M.D.d and Prof. InmaculadaMontoya-Castilla, M.D.e

a. School of Psychology, Department of Personality, Assessment and Psychological Treatments.

b. Unit of Pediatric Pulmonology and Cystic Fibrosis of Hospital Clínico y Universitario de Valencia.

c. Department of Social Psychology, School of Psychology.

d. Department of Personality, Assessment and Psychological Treatments, School of Psychology.

e. Department of Personality, Assessment and Psychological Treatments, School of Psychology. Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

E-mail address: Inmaculada Montoya-Castilla, M.D.: inmaculada.montoya@ uv.es

Funding: This study was funded by the research aids granted by the Spanish Association of Clinical Psychology and Psychopathology and the Spanish Federation of Family Therapy Associations, and by a predoctoral grant provided by the Valencian autonomous government and the European Social Fund (ACIF17).

Conflict of interest: None.

Received: 7-27-2018

Accepted: 12-17-2018

ABSTRACT

Introduction. The Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire Self-Administered Standardized (CRQ-SAS) format is used to assess health-related quality of life in different languages and adult populations, but it has not been validated in adolescents. This study analyzes the psychometric properties of the CRQ-SAS in a sample of adolescent patients with chronic respiratory disease and correlates them to anxiety and depression.

Method. In relation to the CRQ-SAS psychometric properties, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were done to assess the instrument's reliability and validity. Correlations and multiple linear regressions with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale were done to assess the relation with anxiety and depression. The mean difference was estimated based on sociodemographic outcome measures.

Results. The CRQ-SAS was administered to 280 children and adolescents with chronic respiratory disease aged 9-18 years (mean=12.02), with a similar male-female distribution. The original 4-factor structure was maintained; 3 items were removed from the original scale and a new 17-item version was obtained. This showed adequate psychometric properties and discriminant validity. The dyspnea and emotional functioning domains better predicted anxiety and depression. Lastly, scales were obtained for the interpretation of health-related quality of life scores.

Conclusions. This questionnaire, which has been previously used in the adult population, may be an adequate instrument to assess health-related quality of life in adolescent patients with chronic respiratory disease.

Key words: CRQ-SAS; Health-related quality of life; Chronic respiratory disease; Adolescent; Psychometry.

INTRODUCTION

At present, according to the World Health Organization (WHO),1 hundreds of millions of people suffer the consequences of chronic respiratory disease (CRD). In fact, approximately 235 million people suffer asthma; 64 million people, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); and millions more, other CRDs, which often go undiagnosed.1

In Spain, according to the National Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE), lower respiratory tract diseases were the fifth most common cause of death, and the third among men.2 It could be stated that CRDs account for approximately 12 % of all deaths and for 4.2 % of deaths among children younger than 15 years.2 The most prevalent CRD in childhood and adolescence is asthma,1,3 which affects 5-14 % of adolescents aged 13-14 years in Spain;4 males have twice the risk for CRD at this age than females.4

CRDs are highly disabling, therefore causing a negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). HRQoL has been defined as a "multidimensional construct that comprises an individual's physical, psychological and social well-being as perceived by such individual."5 In CRDs, HRQoL instruments are used as indicators of treatment success because they demonstrate disease interference with daily life and the level of adaptation to disease based on several functioning areas (social, emotional or physical). It has been observed that, in adolescents, a poor respiratory symptom control could lead to a greater HRQoL deterioration6 due to interference with daily life activities. Likewise, it increases concern for a new crisis and school absenteeism rates.7 As age advances, HRQoL decreases.8

A HRQoL-related outcome measure in pediatric chronic conditions are the emotional symptoms caused by disease. As a result, it has been observed that, in this type of patients, anxiety9 or depression10 may reduce their HRQoL.

Studies have suggested the need to use specific HRQoL measures.11 Different instruments have been implemented to assess HRQoL; some may be generally applied to any type of disease (the Nottingham Health Profile or the SF-36),12 while others focus on specific diseases, such as the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ).13 The most common instrument used in CRD patients is the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ),14 developed for COPD patients.14 The effectiveness of the CRQ has been demonstrated in a large variety of studies,15-17 but mainly in the adult population,1718 not in adolescents. The Spanish version of the CRQ14 was translated and validated for its use in the German and Latin American populations, and some items were removed for its subsequent application.1517 In spite of the adequate psychometric properties of the CRQ,1519 the original questionnaire depended on an interviewer; for this reason, the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire Self-Administered Standardized (CRQ-SAS) format18 has been recently developed and validated in different languages1517,20,21 for the adult population,22-24 and can be administered more easily and rapidly.

The main objective of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the CRQ-SAS for its use in the pediatric population. The specific objectives of this study were to analyze its reliability and validity in pediatric patients with CRD, assess the relation with anxiety and depression, analyze the differences in HRQoL based on sociodemographic outcome measures, and obtain scales for score interpretation.

METHODS

Design

This was a cross-sectional, single-pass study. The SPSS software (version 24.0), the structural equation modeling software (version 6.3), and the FACTOR software25 were used for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The EFA was done in line with the process recommended by Lloret-Segura.26

Item properties were analyzed based on item-total correlation coefficients and variations in Cronbach's alpha coefficients, if items were removed. Psychometric properties were tested using an EFA and a CFA. The latter was used to validate the scales' factor structure based on Satorra-Bentler's goodness of fit and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The suitability of the CFA was tested using Satorra-Bentler's robust correction and χ2significance (S-B χ2).27 Adequacy of goodness-of-fit indices were tested using the comparative fit index (CFI) and the incremental fit index (IFI); values ≥ 0.90 were considered adequate.28 Finally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was included in the sample; the score had to be ≤ 0.08.28 Predictive validity was assessed using Pearson's correlations and multiple linear regressions with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to analyze discriminant validity. The mean difference in relation to sociodemographic outcome measures was estimated using t tests for independent samples.

Instruments

Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire Self-Administered Standardized (CRQ-SAS).20 This instrument is made up of 20 items grouped into 4 domains20 (dyspnea, fatigue, emotional functioning and disease control). Items are grouped as follows: for dyspnea, items 1-5; for fatigue, items 8, 11, 15, 17; for emotional functioning, items 6, 9, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20; and, finally, for disease control, items 7, 10, 13, 19. A 7-point Likert-like scale was used for answers, where 1 means maximal involvement and 7, no involvement at all. Prior studies have shown its adequate psychometric properties.15,17,20

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.29 This is a 14-item Likert scale used to assess the cognitive symptoms of anxiety and depression. Each item is rated as per a 4-point frequency scale, from 0 to 3. A higher score indicates a higher level of anxiety and depression symptoms. Prior studies have observed its adequate psychometric properties.30

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de Valencia and the committee of the participating hospital. Data were collected between July 2015 and December 2017, once informed consents were signed by legal tutors and patients had given their assent.

RESULTS

Participants were pediatric patients with CRD aged 9-18 years (mean = 12.02, standard deviation [SD] = 2.44); 52.1 % were males. The sample was made up of 280 participants seen at the Unit of Pediatric Pulmonology: 53.2 % (n = 149) had asthma; 8.9 % (n = 25), cystic fibrosis; 10 % (n = 28), obliterative bronchiolitis; 4.3 % (n = 12), primary ciliary dyskinesia; and 23.7 % (n = 66), other CRDs (e.g., alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, bronchiectasis, recurrent pneumonia, among others).

Item and reliability analysis

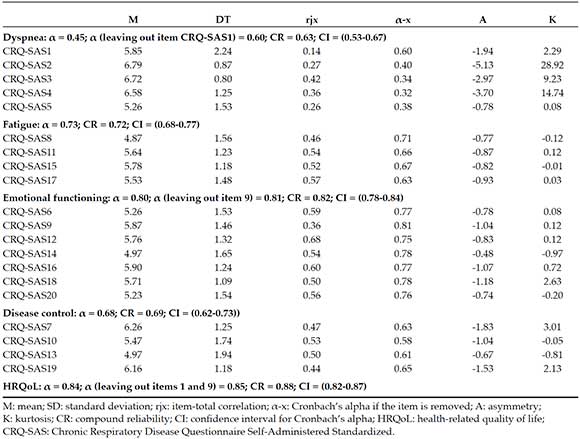

The instrument was made up of 20 items grouped in 4 domains. After analyzing items, the reliability analysis suggested the removal of items 1 and 9 to increase the alpha of their corresponding factors and the overall domain (Table 1). In general, all domains showed acceptable coefficients, except for dyspnea, which was below 0.70.

Table 1. Item and reliability analysis

Instrument's validity analysis

After analyzing the psychometric properties of the items, the instrument's internal validity was established using the EFA and the CFA. Before performing the analyses, data adequacy was determined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett's sphericity test. The KMO showed an adequate value (KMO = 0.85), as well as Bartlett's sphericity test (χ2= 1667.83, df = 190; p ≤ 0.001), so the EFA and the CFA were performed.

a) Exploratory factor analysis

It was estimated based on the original scale. After applying it in a fixed manner to the 4 domains, it was necessary to remove those items whose saturation was below 0.40 or higher in more than 1 factor; therefore, 4 items were removed (1, 8, 11, 17). Such factor resolution showed adequate fit indices (RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 0.98). The explained variance for the 4 domains was 59.78 %.

b) Confirmatory factor analysis

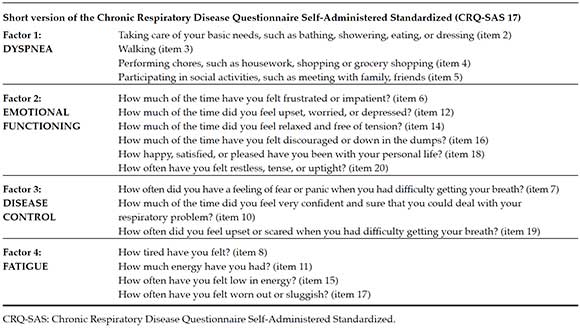

After applying the EFA recommendations, the CFA was performed. The goodness-of-fit indices for the 4-factor resolution in the 20-item version were inadequate. Therefore, items with factor loading problems, ≤ 0.30 score, were removed, thus resulting in a significantly improved model once 3 items (1, 9, 13) were removed (Table 2). The same procedure was repeated for the single factor resolution, the same number of items was removed, and the model was deemed inadequate. The results showed that the 4-factor resolution was the better option. Finally, a short 17-item version of the questionnaire was obtained (Table 3).

Table 2. Fit indices of the confirmatory factor analysis for four factor resolutions and single factor resolution

Table 3. Short version of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire Self-Administered Standardized with selected items

Then, the relation among the different instrument domains was analyzed using Pearson's correlations. Positive and moderate statistically significant relations were observed among all domains.

The instrument's criterion validity was established based on the determination of the relation between the CRQ-SAS and other constructs suggested in the bibliography. Pearson's correlation coefficient and regression analyses for the different CRQ-SAS and HADS domains were performed (Table 4). Correlation coefficients were negative (a lower score indicated a better HRQoL), low or moderate, and significant (p ≤ 0.01, between -0.19 and -0.64). Correlations between the CRQ-SAS and age were negative and significantly low (p ≤ 0.01) for emotional functioning and for total HRQoL, but not significant in relation to the other scales.

Table 4. Correlations among the domains of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire Self-Administered Standardized and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

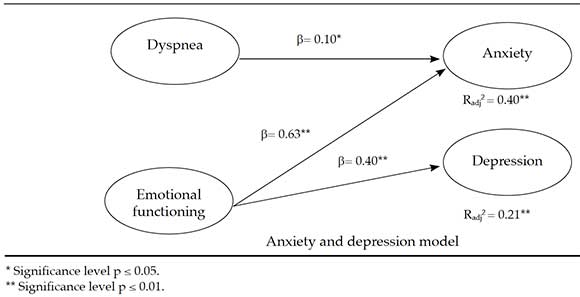

Continuing with criterion validity, two multiple regression linear analyses were done; the anxiety and depression domains were the criterion variables and the different CRQ-SAS factors were predictor variables. The following were the main results of the final models:

a) They predicted anxiety, dyspnea, and emotional functioning in a negative direction (Figure 1).

b) Emotional functioning predicted depression in a negative direction (Figure 1).

Figure 1. HADS domain prediction as per CRQ-SAS domains

Mean difference

For the analysis of differences in HRQoL based on sex and age, participants were grouped into preadolescents aged 9-12 years and adolescents aged 12-18 years, similar to what was done in other studies.7 No difference was observed in any of the domains in terms of sex; however, age showed differences among the domains: fatigue (t205 = 2.79, p ≤ 0.01, d = 0.34), emotional functioning (t206 = 2.63, p ≤ 0.01, d = 0.38), and total HRQoL (t196 = 2.15, p ≤ 0.05, d = 0.27). Preadolescents showed higher HRQoL levels in terms of fatigue, emotional functioning, and total HRQoL.

Percentiles to interpret health-related quality of life in pediatric pulmonology patients

Finally, after completing the analysis of the CRQ-SAS psychometric properties, a reference table with scales was developed to facilitate the interpretation of data obtained in this study (Table 5).

Table 5. Scales based on age for pediatric patients with chronic respiratory disease (n = 280)

DISCUSSION

The presence of a CRD in adolescence has a negative impact on a patient's HRQoL.6,7 The results indicate that the CRQ-SAS, a questionnaire that is widely used to assess HRQoL in CRD22-24 in several countries,15,17,21 is valid and reliable for its use in adolescents with CRD.

After analyzing its psychometric properties, the number of items was reduced, thus obtaining the version presented in this study. This short version contains 17 items distributed into 4 factors, as suggested in the original scale.20 Both reliability and validity results suggest adequate psychometric properties. Reliability results are adequate and similar to those observed in previous studies in adults.17,19 The fit indices obtained with the CFA indicate that the proposed 4-factor model has an adequate fit. As suggested in prior studies,21,22,24 some items show an erroneous factor loading and may result repetitive; therefore, in our study, 3 items were removed from the original scale.

A relation has been demonstrated between HRQoL and anxiety and depression (criterion validity), which was this study's objective. Thus, regression models suggest that the main predictive outcome measure of anxiety and depression symptoms is emotional functioning (feeling anxious, worried), which is consistent with the fact that anxiety and depression have a negative impact on the psychological aspects of HRQoL.9,10 In addition, dyspnea (shortness of breath while doing daily activities) is a predictor of anxiety, which, in the case of CRD, shows a two-way relation: greater shortness of breath leads to greater anxiety and vice versa. In terms of age, older participants showed a worse quality of life, as suggested by prior studies.7

In relation to the third objective of this study, the analysis of the impact of sociodemographic outcome measures on HRQoL showed no differences for sex, whereas it did for age. Adolescents have a worse HRQoL, specifically in the fatigue and emotional functioning domains. This may be because they have a greater awareness of their disease and the loss of autonomy in relation to medical treatments.7

We find the use of this instrument for any type of CRD in the adolescent population innovative because, in general, HRQoL instruments are in English and aimed at the adult population. Although there are other questionnaires related to HRQoL that can be used in our population, they focus on specific diseases, such as asthma or cystic fibrosis. Therefore, it may be useful for any pediatric CRD and is easily administered by individuals themselves, without the help of a trained professional. This reduces the time of administration compared to other questionnaires. Although the data used in our study correspond to a cross-sectional design, this questionnaire may be used in a longitudinal study to observe changes in respiratory rehabilitation or physical therapy techniques in relation to HRQoL.20

In spite of the contributions made by this study, it has limitations. First of all, the sampling procedures corresponded to non-probability sampling and, in general, the sample was not representative of all CRDs. Our sample included a higher proportion of patients with bronchial asthma and obliterative bronchiolitis compared to other diseases, which prevents the generalization of outcomes. Further studies with probability sampling and with samples from other countries are required. Although such limitation is common in the studies conducted in this field, the large sample size-larger than in other studies- renders these results a useful initial approach to the study subject matter. Another limitation of this study is the use of self-reports for data collection. Self-reports are frequently used in research but may introduce social desirability bias. Therefore, it would be advisable to use other tools and/or external objective measures (e.g., spirometry or plethysmography values). This study is interesting, especially in relation to the lack of generic HRQoL questionnaires in the pediatric pulmonology bibliography.

CONCLUSION

The CRQ-SAS is a valid and practical instrument to assess HRQoL in patients with CRD. This study provides a short questionnaire version that enables to broaden the age range for its implementation and facilitates its administration, even by specialists themselves.

3. Bercedo Sanz A, Redondo Figuero C, Lastra Martínez L, Gómez Serrano M, et al. Prevalencia de asma bronquial, rinitis alérgica y dermatitis atópica en adolescentes de 1314 años de Cantabria. Bol Pediatr. 2004; 44(187):9-19. [ Links ]

4. GEMA. Guía española para el manejo del asma 4.2. Madrid: Luzan; 2017. [Consulta: 3 de abril de 2018]. Disponible en: https://www.semfyc.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/GEMA_4.2_final.pdf.

5. Abbott J, Hart A, Havermans T, Matossian A, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in clinical trials in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011; 10(Suppl 2):S82-5. [ Links ]

6. Lima L, Guerra MP, Lemos MS. The Psychological Adjustment of Children with Asthma: Study of Associated Variables. Span J Psychol. 2010; 13(1):353-63. [ Links ]

7. Sullivan P, Ghushchyan VG, Navaratnam P, Friedman HS, et al. School absence and productivity outcomes associated with childhood asthma in the USA. J Asthma. 2017; 55(2):161-8. [ Links ]

8. Ravens-Sieberer U, Auquier P, Erhart M, Gosch A, et al. The KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Qual Life Res. 2007; 16(8):1347-56. [ Links ]

9. Van den Brink G, Stapersma L, El Marroun H, Henrichs J, et al. Effectiveness of disease specific cognitive-behavioural therapy on depression, anxiety, quality of life and the clinical course of disease in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: study protocol of a multicentre randomised controlled trial (HAPPY-IBD). BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016; 3(1):e000071. [ Links ]

10. Ojeda Zambrano C, Cofré Dougnac C. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en pacientes pediátricos con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2018; 89(2):196-201. [ Links ]

11. Everhart RS, Fiese BH. Asthma severity and child quality of life in pediatric asthma: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 75(2):162-8. [ Links ]

12. Sundh J, Johansson G, Larsson K, Lindén A, et al. Comorbidity and health-related quality of life in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease attending Swedish secondary care units. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015; 10:173-83. [ Links ]

13. Zaragoza J, Lugli-Rivero Z. Construcción y validación del instrumento Calidad de Vida en Pacientes con Enfermedades Respiratorias Crónicas (CV-PERC). Resultados preliminares. Arch Bronconeumol. 2009; 45(2):81-6. [ Links ]

14. Güell R, Casan P, Sangenís M, Morante F, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic respiratory disease: The Spanish version of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ). Eur Respir J. 1998; 11(1):55-60. [ Links ]

15. Bourbeau J, Maltais F, Rouleau M, Guímont C. French-Canadian version of the Chronic Respiratory and St George's Respiratory Questionnaires: An assessment of their psychometric properties in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J. 2004; 11(7):480-6. [ Links ]

16. Wijkstra P, TenVergert E, Van Altena R, Otten V, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ). Thorax. 1994; 49(5):465-7. [ Links ]

17. Puhan MA, Guyatt GH, Goldstein R, Mador J, et al. Relative responsiveness of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire, St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire and four other health-related quality of life instruments for patients with chronic lung disease. Respir Med. 2007; 101(2):308-16. [ Links ]

18. Bravo Bolaños MP, Delgado Serra LJ, Agredo Ceron R, Rodríguez S, et al. Calidad de vida de los pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica que se encuentran en el servicio de hospitalización y urgencias del hospital universitario San José de la ciudad de Popayán. Mov Cient. 2013; 7(1):124-35. [ Links ]

19. Güell R, Casan P, Sangenís M, Sentís J, et al. Traducción española y validación de un cuestionario de calidad de vida en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica. Arch Bronconeumol. 1995; 31(5):202-10. [ Links ]

20. Vigil L, Güell MR, Morante F, López De Santamaría E, et al. Validez y sensibilidad al cambio de la versión española autoadministrada del cuestionario de la enfermedad respiratoria crónica (CRQ-SAS). Arch Bronconeumol. 2011; 47(7):343-9. [ Links ]

21. Schünemann HJ, Puhan M, Goldstein R, Jaeschke R, et al. Measurement properties and interpretability of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ). COPD. 2005; 2(1):81-9. [ Links ]

22. Al Moamary MS, Tamim HM. The reliability of an arabic version of the self-administered standardized chronic respiratory disease questionnaire (CRQ-SAS). BMC Pulm Med. 2011; 11:21. [ Links ]

23. Jones PW, Harding G, Wiklund I, Berry P, et al. Tests of the responsiveness of the COPD assessment test following acute exacerbation and pulmonary rehabilitation. Chest.

2012; 142(1):134-40.

24. Watkins ML, Wilcox TK, Tabberer M, Brooks JM, et al. Shortness of breath with daily activities questionnaire: Validation and responder thresholds in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(10):e003048. [ Links ]

25. Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav Res Methods. 2006; 38(1):88-91. [ Links ]

26. Lloret-Segura S, Ferreres-Traver A, Hernández-Baeza A, Tomás-Marco I. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. An Psicol. 2014; 30(3):1151-69. [ Links ]

27. Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test stadistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In Von Eye A, Clogg CC (eds.). Latents variable analysis: applications to developmental research. Thousand OAKS, CA; SAGE; 1994. [ Links ]

28. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, (eds.). Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1993. [ Links ]

29. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67(6):361-70. [ Links ]

30. Caro Gabalda I, Ibañez E. Escala hospitalaria de ansiedad y depresión. Su utilidad práctica en Psicología de la Salud. Bol Psicol. 1992; 36:43-9. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em