Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Archivos argentinos de pediatría

versão impressa ISSN 0325-0075versão On-line ISSN 1668-3501

Arch. argent. pediatr. vol.117 no.6 Buenos Aires dez. 2019 Epub 01-Dez-2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2019.381

Original articles

Prognostic factors of severity of invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children

aInstituto de Medicina Tropical

bUniversidad Nacional de Asunción, Paraguay

Objective

To describe the clinical characteristics of invasive Staphylococcus aureus infections inchildren and identify the prognostic factors ofseverity and mortality.

Materials and methods

Observational study in patients < 16 years old hospitalized between 2010and 2015 due to invasive S. aureus infections atthe Instituto de Medicina Tropical, in Asunción, Paraguay. Patients were distributed based onwhether or not they required admission to theintensive care unit, and clinical, laboratory, and evolutionary outcome measures werecompared.

Results

Out of the 107 included patients, 50 (47 %) developed bacteremia; 50 (47 %), pneumonia; and 21 (19 %), multifocal disease. Among the patients who were admitted tothe intensive care unit (41 %), prior antibioticuse (p < 0.05), the presence of bacteremia (p = 0.01), the presence of comorbidities (p < 0.05), and multifocal disease (p < 0.01) were more frequent. The overall mortality ratewas 15 %. The mortality-associated risk factorswere the presence, at the time of admission, of hypotension (p < 0.01), multifocal disease (p < 0.01), bacteremia (p < 0.01), leukopenia (p < 0.01), severe anemia (p < 0.01), and metabolicacidosis (p < 0.01), among others.

Conclusions

The prognostic factors of severity included prior antibiotic use, bacteremia, thepresence of comorbidities, and presentationwith multifocal disease. Mortality wassignificant; associated risk factors includedthe presence, at the time of admission, ofhypotension, multifocal disease, leukopenia, severe anemia, and metabolic acidosis.

Key words Staphylococcus aureus; Invasive staphylococcal infections; Children; Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

In the past two decades, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections have emerged worldwide.1,3 In Latin America, the first cases ofcommunity-acquired (CA) MRSA infections were reported in Uruguayin 2001;4 after this, several countries,5,8 including Paraguay,9 have reportedthat the prevalence of methicillinresistance ranges from 25 % to 70 %.10

Taking into account the severity associated with community-acquired S. aureus infections,11 in this newsetting of antimicrobial susceptibility, it is especially relevant to identifythe factors inherent to the host andbacteria, which may be consideredprognostic factors of severity atthe time of patient hospitalization. Although several studies haveassessed these factors in the adultpopulation, the information in thisregard in the pediatric populationis limited. Therefore, the objectiveof this study was to describe theclinical characteristics of invasive Staphylococcus aureus infections inchildren and identify the prognosticfactors of severity and mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and design

This was a descriptive, retrospective, and cross-sectionalstudy carried out at the Institutode Medicina Tropical, in Asunción, Paraguay, the leading national referralfacility for infectious diseases. Patientsyounger than 16 years, diagnosedupon discharge with invasive S. aureus infection and hospitalizedbetween 2010 and 2015 were included.

Invasive S. aureus infection was defined as the presence of an infection with concomitant isolation of S. aureus in usually sterile sites, including blood, pleuralfluid, cerebrospinal fluid, joint fluid, bone, pericardial fluid, peritoneal fluid or otherinternal body site. Cases of infections limitedto the skin and soft tissue were excluded, unless they were associated with a systemicinflammatory response syndrome. Patientswho were transferred from other facilities, whohad an incomplete medical record in terms ofstudy outcome measures, and who had S. aureus isolation in samples collected after 48 hours ofhospitalization were excluded.

Data were collected in a standardized sheet. The following outcome measures wereincluded: clinical, demographic (sex, age, comorbidity), type of infection (multiplesources, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, myocarditis, meningitis, endocarditis), laboratory (whiteblood cells [WBC], hemoglobin, platelets, hypoalbuminemia, bacteremia, etc.), microbiological (susceptibility pattern), andevolutionary (need for admission to theintensive care unit [ICU], assisted mechanicalventilation [AMV], presence of kidney or liverfailure). The microbiological characteristicsof S. aureus and antimicrobial sensitivitywere established using the Vitek® automatedidentification system (Bio Merieux).

Patients with hypotension, respiratory insufficiency (oxygen saturation [Sa O2] < 90 %on room air or a fraction of inspired oxygen[Fi O2] > 50 % required to maintain Sa O2 at92 % or higher), poor respiratory dynamics (accessory muscle use, nasal flaring, respiratoryrate > 2 standard deviations [SDs] for age) or aconsciousness disorder required admission tothe ICU.

Statistical analysis

After the general analysis, patients were stratified based on whether or not they hadbeen admitted to the ICU and on their statusupon discharge (dead or alive). The differentdemographic, clinical, and laboratory outcomemeasures, and their association with the severityof invasive S. aureus infections were analyzedin relation to ICU admission and mortality. Comparative analyses were done using Student'st test for parametric outcome measures and the X2 test to compare proportions. To analyze riskfactors, the odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding95 % confidence interval (CI) were estimated.

RESULTS

General characteristics

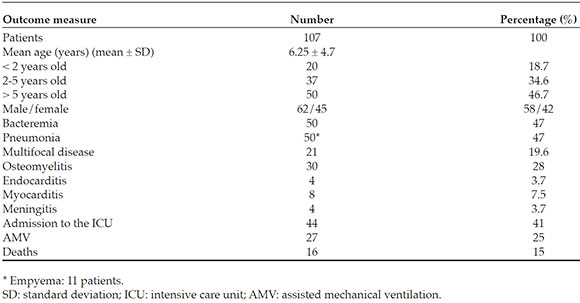

During the study period, 418 patients were hospitalized with S. aureus isolation in a sterilesite in the first 48 hours of admission. Of them,107 (26 %) had invasive infections. The patients'mean age was 75 ± 56 months, with a slightprevalence of male sex (58 % versus 42 %). Moreinfections were observed in children older than5 years (n = 50) compared to those younger than2 years (n = 20) and to the 2-5 year-old group (n = 37) (p < 0.05).

Invasive infections corresponded to pneumonia (n = 50), osteomyelitis (n = 30), multifocal disease (n = 21; in 2 cases, withendocarditis), meningitis (n = 4), and primaryendocarditis (n = 2). Bacteremia was confirmedin 50/107 patients (47 %), which correspondedto 20 % of those with pneumonia (n = 10), 30 %of those with osteomyelitis (n = 9), 100 % ofthose with multifocal disease (n = 21), the 2 casesof primary endocarditis, and the 4 cases ofmeningitis.

Comorbidities were observed in 34 patients (32 %); atopy (n = 11, 10 %) and nutritionaldisorders (malnutrition [ n = 7] and obesity[ n = 4]) were the most common ones. Othercauses of comorbidity included asthma (n = 4), corticosteroid use (n = 4), and humanimmunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (n = 4). In addition, 44 % of patients had receivedantibiotics prior to hospitalization. Most patientshad leukocytosis at the time of admission (X ± SD:16 200 ± 5505/mm3 ), and moderate to severeanemia was observed in 40 cases (37 %). Theoverall mortality rate was 15 % (Table 1).

Characteristics of patients with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infections

Out of 107 S. aureus isolations, 42 (39 %) were resistant to oxacillin (MRSA). Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) infections predominated amongpatients younger than 5 years (69 %), whereas MRSA infections were more common amongthose older than 5 years (70 %) (p < 0.001). Whereas 83 % of MRSA infections were observedin male patients, only 42 % of MSSA infectionscorresponded to male patients (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The frequency of comorbidities (p = 0.02), as wellas pneumonia (p = 0.04), bacteremia (p = 0.01), and multifocal disease (p = 0.02), was higheramong patients with MRSA infections (Table 2). Although no differences were observed inmortality between MRSA and MSSA infections, admission to the ICU was significantly higheramong the patients with MRSA infections (60 %versus 29 %, p = 0.01) (Table 2).

Admission to the intensive care unit

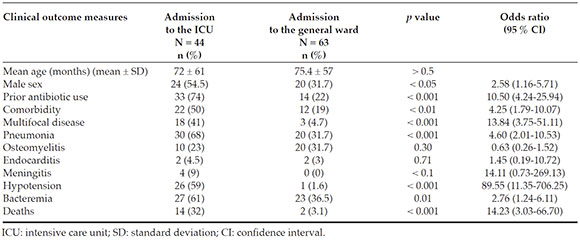

A total of 44 patients (41 %) were admitted to the ICU (Table 3). When comparing thosewho were admitted to the ICU and those whodid not require such admission (n = 63), nodifference was observed in the mean age ofpatients in both groups (72 ± 61 months oldversus 75.4 ± 57 months, p > 0.5); however, malesex predominated among those who requiredit (54.5 % versus 31.7 %) (p < 0.05). Antibioticuse prior to hospitalization (p < 0.001) and the presence of comorbidities (p < 0.01) were more common among the patients admitted to the ICU. When comparing the types of invasive S. aureus infection, the presence of pneumonia (30/44versus 20/63, p < 0.001) and multifocal disease (18/44 versus 3/63, p < 0.001) predominatedamong patients admitted to the ICU (Table 3). Likewise, the presence of bacteremia (p = 0.01) was clearly higher among those admitted to the ICU (Table 3). When comparing the length ofstay, it was longer among the patients admittedto the ICU versus those that did not require it (20 ± 19 days versus 13 ± 15 days, p < 0.05). Lastly, mortality was significantly higher among thepatients admitted to the ICU (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3 Prognostic factors of severity in patients with invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections

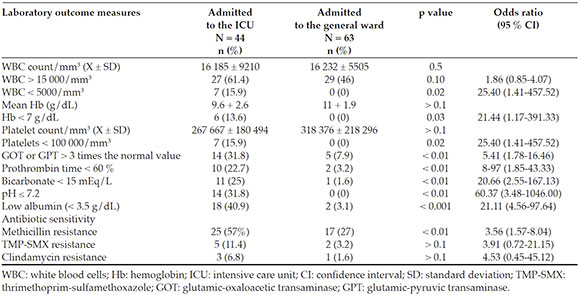

The analysis of lab test characteristics showed that the presence of a WBC count < 5000/mm3 (p = 0.02), severe anemia < 7 g/d L (p = 0.03), and thrombocytopenia < 100 000/mm3 (p = 0.02) were more common among the patients admittedto the ICU (Table 4). Also, a higher number ofpatients admitted to the ICU showed elevatedtransaminases > 3 times the normal value (p < 0.01), metabolic acidosis (p < 0.01), andhypoalbuminemia < 3.5 g/d L (p < 0.001) (Table 4). The frequency of methicillin resistance wassignificantly higher among the patients whorequired admission to the ICU (p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4 Laboratory prognostic factors of severity in patients with invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections

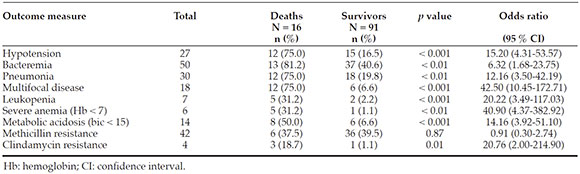

The outcome measures associated with mortality were the presence, at the time of admission, of hypotension (OR: 15.20; 95 % CI: 4.31-53.57; p < 0.001), bacteremia (OR: 6.32; 95 %CI: 1.68-23.75; p < 0.01), pneumonia (OR: 12.16;95 % CI: 3.50-42.19; p < 0.01), and a diagnosis ofmultifocal disease (OR: 42.50; 95 % CI: 10.45-172.71;p < 0.01) (Table 5). In relation to lab test informationat the time of admission, the presence of a WBC count < 5000/mm3 (OR: 20.22; 95 % CI: 3.49-117.03;p < 0.001), severe anemia (hemoglobin < 7 g/d L) (OR: 40.90; 95 % CI: 4.37-382.92; p < 0.01), metabolicacidosis (OR: 40.90; 95 % CI: 4.37-382.92; p < 0.01), and S. aureus isolation with clindamycin resistance (OR: 20.76; 95 % CI: 2.00-214.90; p = 0.01) wereidentified as risk factors associated with mortality. The presence of methicillin resistance was notassociated with a higher mortality (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, all patients with invasive S. aureus infections hospitalized in a referralfacility for infectious diseases in Paraguayin a 5-year period were analyzed. Invasive S. aureus infections were observed mostly inschoolchildren (50 % of cases), and this is similarto what has been reported in other S. aureus bacteremia series conducted in our region, suchas in Argentina or Uruguay.5,7 The fact that theskin is usually the source of S. aureus infectionsand that schoolchildren are more prone to sufferwounds or minor traumas on the skin maypartially explain such observation. However, inother series, especially those carried out in the United States of America (USA)12,13 or Asia,14 community-acquired S. aureus infections weremainly observed in children younger than 3 years.

Although 32 % of patients had a comorbidity which was, in general, of unmarked severity, likeatopy or malnutrition, most patients with invasive S. aureus infections were immunocompetent. Thisis different from other series done both in the USA and Europe.12,15,16

Forty percent of S. aureus causing invasive infections in this series was methicillin-resistant. These findings demonstrate that the growingepidemics of methicillin-resistant S. aureus, whichhas been reported in different countries in boththe Northern and Southern hemispheres, hasnot escaped our country, thus anticipating theincrease in resistance to be seen in the next years.

Our series shows the severity of invasive S. aureus infections. Admission to the ICU wasrequired in 41 % of cases. Although no differenceswere observed in the mean age between thepatients who required admission to the ICU andthose who did not, more male patients requiredit. It is known that sex has a major impact onthe outcomes of a series of infectious diseases.17 The presence of comorbidities was a factorassociated with admission to the ICU, whichis not surprising because the integrity of theimmune system is critical in the response of thehost to the infection.18 In addition, the frequencyof prior antibiotic use was higher among thepatients who were admitted to the ICU. This mayhave affected the delay in the visit to the doctor'soffice for those who were receiving treatment andmay have had an impact on the severity of thecondition. This has already been observed in casesof community-acquired pneumonia.19

The presence of bacteremia (p = 0.01), pneumonia (p < 0.01), and clinical presentationwith multifocal disease (p < 0.01) correlatedto the admission to the ICU. These findingsare not surprising because the presence ofa microorganism in the blood is usuallyaccompanied by cytokine activation, whichleads to a systemic inflammatory responsesyndrome.20 The severity of S. aureus pneumoniahas been widely documented and, in our series, this has been confirmed because 68 % of patientsadmitted to the ICU had pneumonia. In thestudy by M. A. Carrillo-Marquez et al.,21 58 % of pneumonia cases required admission to the ICU. The incidence of metastatic sources in S. aureus bacteremias ranges from 15 % to 68 %in different studies and accounts for a marker of severity.16,22,23

Among the patients admitted to the ICU, MRSA was isolated in 57 %, which was asignificantly higher proportion than amongthose who did not require admission to the ICU (p < 0.01). MRSA infections were more severe (higher frequency of pneumonia, bacteremia, andmultifocal disease) (Table 2), which may explainthe higher frequency of admission to the ICU.

Our study has allowed us to identify laboratory outcome measures associated with agreater severity in the setting of staphylococcalinfections. In this regard, the presence, at thetime of admission, of leukopenia (< 5000/mm3 )(p = 0.02), severe anemia < 7 g/d L (p = 0.03), and thrombocytopenia < 100 000/mm3 (p = 0.02) were significantly more common in the patientsadmitted to the ICU. Such associations hadalready been reported by other authors.24,27

The mortality rate due to invasive S. aureus infections in our study was significant (15 %). Although it was similar to that observed in otherstudies,28 mortality may be higher than 48 %.n H owever, other studies have reported a muchlower mortality rate. Thus, in the study conductedin Argentina by G. Pérez et al.,7 the mortality ratewas 6 %; in the study done in Europe by M. Gijónet al.,15 2 %; in the study by D. Engelman et al.22 or in the one by Mc Mullan et al.,29 in Australia, between 2 % and 4 %; and in the study by J. S. Gerber et al.,12 in the USA, 1 %. The high mortalityrate observed in our series may be partiallyexplained by the severity of cases hospitalized inthis referral facility.

In this study, several mortality-associated risk factors were identified, both clinical (presence, at the time of admission, of hypotension, pneumonia, multifocal disease) and laboratory (bacteremia, leukopenia, severe anemia, andmetabolic acidosis). Some of these have alreadybeen reported in other studies.15,23,30

Our study poses several limitations. Since the inclusion criterion was S. aureus isolation, thereis a potential bias that cultures were collectedin patients who appeared to have a more severecondition at the emergency department. Besides, since the Instituto de Medicina Tropical is areferral hospital for infectious diseases, ourpopulation possibly accounts for the most severecases observed in the community. Therefore, our results may not be fully extrapolated to thepopulation of a general hospital.

Future multicenter studies are required to more clearly elucidate risk factors and definethe most effective treatment regimens aimed atreducing the morbidity and mortality in invasive S. aureus infections.

REFERENCIAS

1. De Leo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2010;375(9725):1557-68. [ Links ]

2. Kaplan S. Community-acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2006;17(3):113-9. [ Links ]

3. Deurenberg RH, Vink C, Kalenic S, Friedrich AW, et al. Themolecular evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcusaureus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(3):222-35. [ Links ]

4. Galiana Villar A. Infección por Staphylococcus aureus meticilino-resistente adquirido en la comunidad. Arch Pediatr Urug. 2003;74(1):26-9. [ Links ]

5. Pardo L, Vola M, Macedo-Viñas M, Machado V, et al. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children treated in Uruguay. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(1):10-6. [ Links ]

6. Paganini H, Dela Latta MP, Muller Opet B, Ezcurra G, et al. Estudio multicéntrico sobre las infecciones pediátricas por Staphylococcus aureus meticilino-resistente provenientes de la comunidad en la Argentina. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2008;106(5):397-403. [ Links ]

7. Pérez G, Martiren S, Reijtman V, Romero R, et al. Bacteriemia por Staphylococcus aureus adquirido en la comunidad enniños: estudio de cohorte 2010-2014. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2016;114(6):508-13. [ Links ]

8. Acuña M, Benadof D, Jadue C, Homarzábal JC, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resistente a meticilina asociado a lacomunidad (SARM-AC): comunicación de los primeroscuatro casos pediátricos descritos en Hospital de Niños Roberto del Río. Rev Chil Infecto!. 2015;32(3):350-6. [ Links ]

9. Irala Ledezma J, Sanabria G. Progresión de la resistencia a la oxacilina de Staphylococcus aureus aislados entre 20112013 en un hospital de referencia de Asunción-Paraguay. Rev Inst Med Trop (Paraguay). 2017;12(1):5-9. [ Links ]

10. Jones RN, Guzman-Blanco M, Gales AC, Gallegos B, et al. Susceptibility rates in Latin American nations: report froma regional resistance surveillance program (2011). Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(6):672-81. [ Links ]

11. Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603-61. [ Links ]

12. Gerber JS, Coffin SE, Smathers SA, Zaoutis TE. Trends inthe incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in children's hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):65-71. [ Links ]

13. Kumarachandran G, Johnson JK, Shirley D-A, Graffunder E, et al. Predictors of adverse outcomes in children with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22(3):218-26. [ Links ]

14. Qiao Y, Ning X, Chen Q, Zhao R, et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in Chinese children. BMCInfect Dis. 2014;14:582. [ Links ]

15. Gijón M, Bellusci M, Petraitiene B, Noguera-Julian A, et al. Factors Associated with Severity in invasive community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children: aprospective European multi-center study. Clin Microbio!Infect. 2016;22(7):643.el-6. [ Links ]

16. Le J, Dam Q, Tran T, Nguyen A, et al. Epidemiology and hospital readmission associated with complications of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in pediatrics over a 25-year period. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(12):2631-9. [ Links ]

17. Muenchhoff M, Goulde PJR. Sex differences in pediatric infectious diseases. J Infect Dis. 2014;209 Supl 3:S120-6. [ Links ]

18. Boyd JH, Russell JA, Fjell CD. The meta-genome of sepsis: host genetics, pathogens and the acute immune response. J Innate Immun. 2014;6(3):272-83. [ Links ]

19. Emery DP, Milne T, Gilchrist CA, Gibbons MJ, et al. The impact of primary care on emergency departmentpresentation and hospital admission with pneumonia: acase-control study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:14113. [ Links ]

20. Bosmann M, Ward PA. The inflammatory response insepsis. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(3):129-36. [ Links ]

21. Carrillo-Marquez MA, Hulten KG, Hammerman W, Lamberth L, et al. Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in children in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistance at Texas Children's Hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(7):545-50. [ Links ]

22. Engelman D, Hofer A, Davis JS, Carapetis JR, et al. Invasive Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Children in Tropical Northern Australia. J Pediat Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3(4):304-11. [ Links ]

23. Miles F, Voss L, Segedin E, Anderson BJ. Review of Staphylococcus aureus infections requiring admission toa paediatric intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(12):1274-8. [ Links ]

24. Gillet Y, Vanhems P, Lina G, Bes M, et al. Factors predictingmortality in necrotizing community-acquired pneumoniacaused by Staphylococcus aureus containing Panton-Valentine leukocidin. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):315-21. [ Links ]

25. Khanafer N, Sicot N, Vanhems P, Dumitrescu O, et al. Severe leukopenia in Staphylococcus aureus necrotizing, community-acquired pneumonia: risk factors and impacton survival. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:359. [ Links ]

26. Muady GF, Bitterman H, Laor A, Vardi M, et al. Hemoglobin levels and blood transfusion in patients with sepsis in Internal Medicine Departments. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):569. [ Links ]

27. Wang JL, Chen SY, Wang JT, Wu GH, et al. Comparison of both clinical features and mortality risk associatedwith bacteremia due to community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(6):799-806. [ Links ]

28. Gonzalez BE, Martinez-Aguilar G, Hulten KG, Hammerman WA, et al. Severe staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):642-8. [ Links ]

29. Mc Mullan BJ, Bowen A, Blyth CC, Van Hal S, et al. Epidemiology and mortality of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in Australian and New Zealand children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(10):979-86. [ Links ]

30. Bassetti M, Trecarichi EM, Mesini A, Spanu T, et al. Risk factors and mortality of healthcare-associated and community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;8(9):862-9. [ Links ]

Received: November 29, 2018; Accepted: June 2, 2019

texto em

texto em