Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Archivos argentinos de pediatría

versión impresa ISSN 0325-0075versión On-line ISSN 1668-3501

Arch. argent. pediatr. vol.117 no.6 Buenos Aires dic. 2019 Epub 01-Dic-2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.5546/aap.2019.388

Original articles

Predictive outcome measures of adult short stature in patients with severe acquiredautoimmune hypothyroidism

aDepartment of Pediatric Endocrinology. Hospital de Pediatria "Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan", Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

bLaboratory of Pediatric Endocrinology. Hospital de Pediatria "Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan", Autonomous City of Buenos Aires

Hypothyroidism caused by Hashimoto's thyroiditis is the most common reason for thyroiddysfunction in children. Our objective was to analyze its impact on final stature in relation to height and pubertalstage at the time of diagnosis in childrenyounger than 18 years with severe autoimmunehypothyroidism. Out of 79 patients, 78.5 %were girls. Those with goiter (56 %) had a betterheight at diagnosis than those without goiter (mean standard deviation score for height: 0.2 versus -2.42; p < 0.0001). Five girls (6.3 %) had precocious puberty. When considering the finalstature of patients (n: 33), among those with shortstature at the time of diagnosis, pubertal childrenhad a significantly shorter final stature thanprepubertal children (mean standard deviationscore for height: -2.82 versus -1.52; p = 0.0311). The late diagnosis of severe hypothyroidism inpediatrics has a negative impact on final stature, especially in those who were pubertal patientsat the time of diagnosis.

Key words Hypothyroidism; Hashimoto's thyroiditis; Stature; Precocious puberty

INTRODUCTION

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (CLT) is the most common causeof acquired hypothyroidism inchildhood and adolescence; itsprevalence is close to 2 % in childrenand it predominates among females (4:1).1,2 The clinical presentation ofacquired hypothyroidism is moresevere with older age at the time ofdiagnosis, with greater involvementof final stature.2

The bibliography regarding the impact on final stature in childrenwith severe acquired hypothyroidism (SAH) is scarce, so our objective wasto detect the patients with greater riskfor adult short stature in relation topubertal stage and height at the timeof diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Descriptive, retrospective study in patients younger than 18 yearsdiagnosed with SAH caused by CLT, seen between 2008 and 2014 at atertiary care children's hospital.

The inclusion criteria at the time of diagnosis were thyroid stimulatinghormone (TSH) level > 50 µIU/m L, low thyroid hormone levels for thereference ranges for age, and positiveantithyroid antibodies (anti-thyroidperoxidase antibodies [TPOAb] orultrasensitive anti-thyroglobulinantibodies [Tg Ab]). Patients with anycondition that may have affected theirgrowth were excluded.

The following outcome measures were analyzed: sex, age, height, pubertal stage, bone age (BA) at thetime of diagnosis, and presence ofgoiter in the subsequent visits. Heightwas described as standard deviationscore (SDS) and adjusted for age and sex. 3 BA was assessed by the same pediatric endocrinologist based on the Greulich and Pylemethod. Mean parental height was estimatedin those patients for whom the height of bothparents was obtained.

Tests were done by chemiluminescence; TSH, T3, and T4L using the Architect i4000 platform (Abbott); and T4, TPOAb, and ultrasensitive Tg Abusing the IMMULITE 2000 platform (Siemens). Previously published reference values wereused for TSH and thyroid hormones. 4 Pubertaldevelopment was assessed as per Tanner'smethodology, and testicular volume, using a Prader orchidometer. Once diagnosed, all patientsstarted replacement therapy with levothyroxine.

Height was considered close to final stature when the growth rate was less than 0.5 cm/yearand/or adult BA was observed. Short staturewas defined as < -2.5 SDS; normal height, as> -2.5 SDS. Patients with height close to finalstature were divided into 4 groups:

Group 1 (G1): prepubertal child with short stature.

Group 2 (G2): prepubertal child with normal height.

Group 3 (G3): pubertal child with short stature.

Group 4 (G4): pubertal child with normal height.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done to study the associations among the differentoutcome measures. The height at the time ofdiagnosis and the height close to final staturewere compared in each group.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and the comprehensiveprotection of patient data was warranted.

RESULTS

A total of 79 patients were assessed; 78 % (n: 62) were girls. The median age at the time ofdiagnosis was 10.9 years (range: 10-12 years).

The analysis of the associations among outcome measures showed that patients withgoiter (n: 45) had a better height at diagnosisthan those without goiter; mean SDS for height:0.2 versus -2.42 (T = -5.13; p < 0.0001).

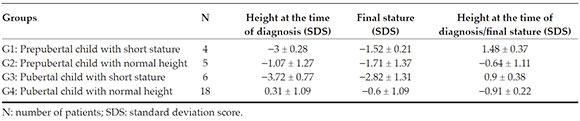

Final stature was obtained only for 33 patients because, to date, some patients have not yetreached their final stature and others were lost tofollow-up (Table 1).

Normal height at the time of diagnosis was observed in 23 patients (G2 and G4); of them,19 reached a normal height for the population (8 within the genetic range and 2 below it; noanthropometric data were obtained about thefathers of the other 9 patients). The remaining4 patients ended up with short stature due to poortreatment adherence.

Ten patients had short stature at the time of diagnosis, and prepubertal children (G1) reacheda significantly higher final stature than pubertalones (G3) (p = 0.0311). The median follow-up ofprepubertal children was 6.83 years, while that ofpubertal children, 2.5 years.

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of G1. The 4 patients reached a normal finalstature for the population (SDS: 1.48 ± 0.37). Girls experienced the menarche 1.5 years later than what has been described for the normalpopulation as per Tanner et al.

Table 2 Evolution of height in prepubertal children with short stature at the time of diagnosis (group 1)

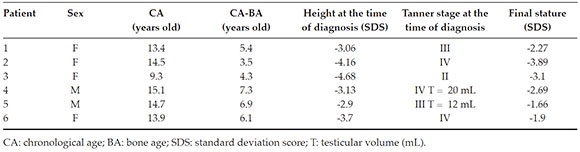

Table 3 shows the clinical characteristics of G3. Patient 2 showed a very poor treatment adherence. Patient 4 was diagnosed at 15.1 years old, onceshe had completed puberty. Patients 3 and 6 hadextreme short stature at the time of diagnosis, sothey were treated with gonadotropin-releasinghormone (Gn RH) analogues. Patient 3 started Gn RH analogues at 10 years old, with Tanner stage III and a height of -3.73 SDS, and discontinuedtreatment at 11.8 years with a BA = 12.5 years. Sheexperienced menarche at 13 years old and her finalstature was -3.13 SDS.

Table 3 Evolution of height in pubertal children with short stature at the time of diagnosis (group 3)

Patient 6 reached a normal final stature for the population, but shorter than her geneticrange (-0.76 SDS). It is striking that, at the timeof diagnosis (13.8 years), she had experiencedmenarche with a 6-year delay in BA and a heightof -3.77 SDS. She received Gn RH analogues for10 months, and discontinued treatment due toproblems with the supply; her final stature was-1.9 SDS.

Five girls (6.3 %) had precocious puberty (PP) at the time of diagnosis (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

SAH in children causes growth failure and a marked delay in skeletal maturation as a resultof a delayed ossification and mineralization, combined with the reduction and down-regulation of growth hormone and insulin-likegrowth factor.5,6

Once replacement therapy with levothyroxine is started, children experience a compensatorygrowth phase, during which the rate of skeletalmaturation exceeds the height gain, thus resultingin a deficit of final stature. Such phenomenon isworsened by the onset of central puberty, whichoften takes place shortly after the initiation ofhormone replacement.7

The objective of this study was to describe the population of pediatric patients with SAH causedby CLT and analyze its impact on their heightclose to final stature based on the SDS for heightand pubertal stage at the time of diagnosis inorder to detect the groups of patients at a greaterrisk for adult short stature.

A clinical presentation without goiter showed greater height involvement. Surely, this was dueto the presence of a clinical sign that alerted aboutthe thyroid disease.

A delay in BA at the time of diagnosis was not a predictor of a higher rate of growth because, after starting hormone replacement therapy, skeletal maturation advanced rapidly, whichis consistent with what has been described by Pantsiouou et al.8

In our study, like in the one by Chiesa et al.,9 it was demonstrated that, in addition to heightdeficit at the time of diagnosis, an advancedpuberty was also a determining factor of finalstature.

Different adjuvant growth therapies have been proposed, including Gn RH analogues, growthhormone-releasing hormone (GHrh) or aromataseinhibitors (Als). Nebesio et al. compared the finalstature of 13 children with severe hypothyroidism (TSH > 150 µIU/m L); 6 of them received adjuvanttreatments (Als, GHrh and/or Gn RH analogues) and 7, levothyroxine only. No differences wereobserved among the groups.10

They reported on 6 children treated with Gn RH analogues who had severe growth failure, higherchronological age, pubertal progression, andadvance of BA, who reached the same height as17 children with a lower height involvement at thetime of diagnosis treated with levothyroxine only.11

Reports of isolated cases12,15 have demonstrated that the combined therapy with GHrh and Gn RH analogues, in addition to levothyroxine, achievedan important increase in the SDS for height inadolescents with severe hypothyroidism and apoor prognosis for their final stature.

The published studies about the effectiveness of adjuvant growth therapies in patients with SAH during childhood and adolescence haveseveral limitations, such as the small numberof patients, their retrospective design, differentfollow-up durations, different levothyroxineinitial doses and subsequent adjustments, and thelack of standard adjuvant therapies.

Although the limitation of our study is the small number of patients in each subgroupthat reached their final stature, we believe thatthe late diagnosis of severe hypothyroidism inpediatrics has a negative impact on it, especiallyin pubertal children with short stature at thetime of diagnosis, for whom adjuvant growththerapies may be considered to improve theirheight prognosis.

Randomized, controlled, and prospective studies are required to elucidate the modifiablefactors related to the loss of potential height inchildren with SAH.

REFERENCIAS

1. Caturegli P, Kimura H, Rocchi R, Rose NR. Autoinmune thyroid diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19(1):44-8. [ Links ]

2. De Vries L, Bulvik S, Phillip M. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis in children and adolescents: at presentation and during long-term follow-up. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(1):33-7. [ Links ]

3. Comité Nacional de Crecimiento y Desarrollo. Guía parala evaluación del crecimiento físico. 3ª ed. Buenos Aires: Sociedad Argentina de Pediatría; 2013. [ Links ]

4. Chaler EA, Fiorenzano R, Chilelli C, Llinares V, et al. Age-specific thyroid hormone and thyrotropin reference intervals for a pediatric and adolescent population. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50(5):885-90. [ Links ]

5. Brent GA. The molecular basis of thyroid hormone action. N Engl J Med. 1994;311(13):847-53. [ Links ]

6. Robson H, Siebler T, Shalet SM, Williams GR. Interactions between GH, IGF-1, glucocorticoids, and thyroid hormones during skeletal growth. Pediatr Res. 2002;52(2):137-47. [ Links ]

7. Boersma B, Otten BJ, Stoelinga GB, Wit JM. Catch-upgrowth after prolonged hypothyroidism. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155(5):362-7. [ Links ]

8. Pantsiouou S, Stanhope R, Uruena M, Preece MA, et al. Growth prognosis and growth after menarche in primary hypothyroidism. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66(7):838-40. [ Links ]

9. Chiesa A, Gruñeiro de Papendieck L, Keselman A, Heinrich JJ, et al. Final height in long-term primary hypothyroid children. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1998;11(1):51-8. [ Links ]

10. Nebesio T, Wise M, Perkins S, Eugster E. Does clinical management impact height potential in children with severe acquired hypothyroidism? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24(11-12):893-6. [ Links ]

11. Quintos JB, Salas M. Use of growth hormone and gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist in addition to L-thyroxine to attain normal adult height in two patients with severe Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005;18(5):515-21. [ Links ]

12. Teng L, Bui H, Bachrach L, Lee P, et al. Catch-up growth in severe juvenile hypothyroidism: treatment with a Gn RH analog. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17(3):345-54. [ Links ]

13. Minamitani K, Murata A, Ohnishi H, Wataki K, et al. Attainment of normal height in severe juvenile hypothyroidism. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70(5):429-30. [ Links ]

14. Bruder JM, Samuels MH, Bremer WJ, Ridgway EC, et al. Hypothyroidism-induced macroorchidism: use of agonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist to understand its mechanism and augment adult stature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(1):11-6. [ Links ]

Received: August 21, 2018; Accepted: June 20, 2019

texto en

texto en