Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina

versión impresa ISSN 0373-5680versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471

Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. vol.77 no.1 La Plata mar. 2018

Trabajo científico - Article

Morphogeometric variation in Phrynus barbadensis (Pocock, 1893) (Amblypyghi: Phrynidae) from Colombia

Variación morfogeométrica en Phrynus barbadensis (Pocock, 1893) (Amblypyghi: Phrynidae) de Colombia

TORRES, Richard A.1, ATENCIA, Pedro L.2 & LIRIA, Jonathan3,4

1 Research Group on Zoology and Ecology. Faculty of Education and Sciences, University of Sucre, Sucre, Colombia. E-mail: richardtorree@gmail.com

2 Research Group on Evolutionary Biology. Faculty of Education and Sciences, University of Sucre, Sucre, Colombia.

3 Universidad Regional Amazónica Ikiam, Napo, Ecuador.

4 Centro de Zoología Aplicada, Carabobo, Venezuela.

Received 08 - XI - 2017 | Accepted 13 - I - 2018 | Published 30 - III - 2018

https://doi.org/10.25085/rsea.770103

ABSTRACT. Amblypygi is a small order of arachnids with features similar to spiders. In Colombia, this order has been subject to low attention, the main investigations are focused towards a taxonomic level. Recently, the geometric morphometrics has proven to be an useful tool for determining shape differences in scorpions and spiders. Due to this, we used geometric morphometrics to determine intraspecific variation in three Colombian populations of Phrynus barbadensis. We digitalized 16 anatomical points over the carapace and 15 in patella by combining landmarks and sliding semilandmarks; the coordinates were aligned by generalized Procrustes analysis. Canonical Variates Analysis was implemented with proportions of re-classifed groups and MANOVA. We found significant differences of carapace conformation between populations; all specimens were 80% correctly classifed. Statistical analyses of variance (ANOVA) found significant differences in carapace and patella isometric size among populations; the main carapace differences occur in anterior, posterior and right margins. The observed variation could be associated with the environmental differences between localities.

KEYWORDS. Conformaron. Intraspecific variation. Procrustes. Whip spiders.

RESUMEN. Amblypygi es un pequeño orden de arácnidos con características similares a arañas. En Colombia, este orden ha sido poco estudiado, y la mayoría de las investigaciones se han centrado a niveles taxonómicos. Recientemente, la morfometría geométrica ha probado ser una herramienta útil para determinar diferencias en escorpiones y arañas. Debido a esto, utilizamos morfometría geométrica para determinar variación intraespecifica en tres poblaciones colombianas de Phrynus barbadensis. Digitalizamos 16 puntos anatómicos sobre el caparazón y 15 en la patela combinando hitos e hitos deslizantes; las coordenadas fueron analizadas mediante análisis generalizado de Procrustes. Se implementó el Análisis de Variables Canónicas con proporción de grupos reclasificados y MANOVA. Se determinaron diferencias significativas en la conformación del caparazón entre poblaciones; todos los especímenes fueron 80% correctamente clasificados. Los análisis estadísticos de varianza (ANOVA) determinaron diferencias significativas en los tamaños isométricos de caparazón y patela entre poblaciones. Las diferencias en el caparazón se asocian con los márgenes anterior, lateral derecho, y posterior. La variación observada podría asociarse a las diferencias ambientales entre localidades.

PALABRAS CLAVE. Araña látigo. Conformación. Procrustes. Variación intraespecífica.

INTRODUCTION

Amblypygi, or whip spiders, is a small order of arachnids with features similar to real spiders. This order is characterized by a dorsoventrally compressed body, segmented abdomen, pedipalps armed with strong spines, and antenniform legs. Phylogenetically, whip spiders are a sister group of Uropigi and Schizomida. They comprise the Pedipalpi clade (Shultz, 1999; Dunlop, 2002). On the other hand, Weygoldt (1998, 2000), and Wheeler & Hayashi (1998) consider Amplypygi as a sister group of Araneae, which comprises the Labellata clade. Amblypygids are mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical areas, found beneath tree barks, under fallen logs, rocks, and inside caves.

Phrynidae is morphologically characterized by the presence of basal tooth, cheliceral hand with a larger lower cusp and abdominal ventral sacs absent. The family is distributed from the south of United States to the north of South America and comprises 66 species in four genera: Acanthophrynus(1 sp.), Heterophrynus (14 spp.), Paraphrynus(18 spp.) and Phrynus(33 spp.). In Colombia, whip spiders have been a subject of low attention, the main investigations are focused towards a taxonomic level. Chiriví & Armas (2012) reported Phrynus barbadensis(Pocock, 1893) in most Colombian localities. Later, Armas & Seiter (2013) synonymized P. gervaisii (Pocock, 1894) collected in San Marcos municipality (Sucre) with P. barbandesis. Recently, Torres-Contreras et al. (2015) increased the data on the distribution of P. barbadensiswith specimens collected in the municipality of Repelon (Atlántico). Armas & Seiter (2013) have examined specimens of P. barbadensis from Barbados, Costa Rica, Colombia, Venezuela, Aruba, and Trinidad y Tobago. These authors explored the variation of some characters: Proximal external tooth of chelicera, tibia articles of leg I, carapace granulation, prosoma frontal process, pedipalps spines, and the general color pattern. However, they did not found relevant taxonomic characters to recognize more than one species. Some authors commented the importance of new tools that quantify the phenotypic variation and covariation with other variables (Rohlf, 2002). The geometric morphometric (GM) is a technique that allows the description of this variation, by decomposition of the "form" into two components: shape and size. The biological structure information is preserved by means of Cartesian coordinates on anatomical landmarks (Toro et al., 2010), and variation can be described as deformation grids. Also, the GM uses a wide range of multivariate statistical methods for shape exploration, confrmatory group membership, and covariation of shape within other variables. Recently, GM was used in scorpions (Bechara & Liria, 2012) and spiders (Fernández-Montraveta & Marugán-Lobón, 2017) for conformation description of sexual dimorphism, respectively. Due to this, we used geometric morphometrics to determine intraspecific variation in three Colombian populations o f P. barbadensis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Material examined

105 P. barbadensis specimens were collected in three localities from the Sucre Department: Colosó (n=37) 09°31'53.705''N; 75°20'57.825''W and 264 masl (19-II-15 / 15-III-16), Sincelejo (n=34) 09°18'14.688''N; 75°24'37.359''W and 212 masl (18-IV-16 / 4-V-16), and El Roble (n=34) 09°06'02.947''N; 75°12'39.650''W and 68 masl (22-30-VI-16). Sincelejo and Colosó correspond to tropical mountain dry forests, while El Roble is associated to savannas and cultivated areas (Aguilera, 2005).

Landmark acquisition

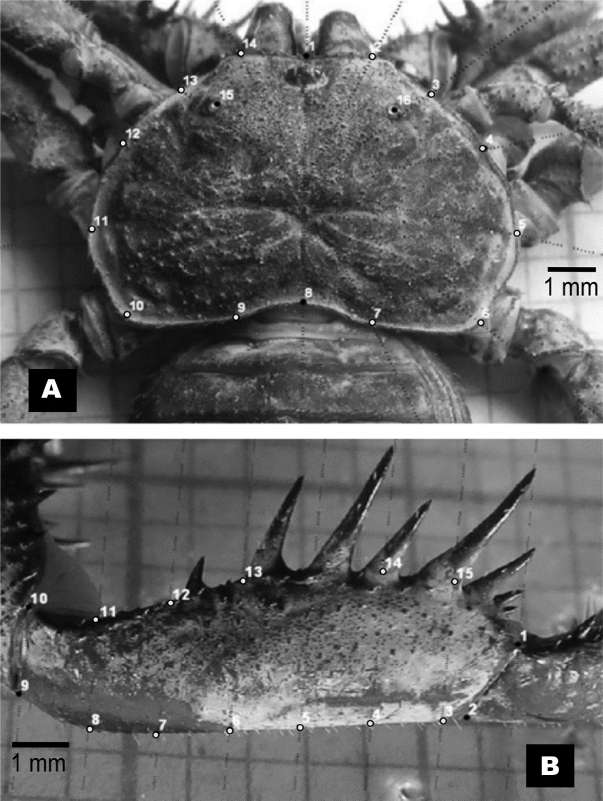

The dorsal surface of carapace and patella (Fig. 1) were photographed. In each structure, equidistant fans and combs were created with MakeFan 7.0 software (Sheets, 2010a) in order to describe conformation outlines. Then, they were digitalized with tpsDig 2.22 software (Rohlf, 2015), anatomical points (x, y coordinates) over each structure (16 landmarks for carapace and 15 in patella), combining type I and II landmarks following Bookstein (1991) criteria:

Carapace

Anterior medial margin between chelicera (LM1), anterior lateral right margin (LM2), lateral right margin close to lateral eyes (LM3), lateral right margin separated between 0.8 mm (LM4 and LM5), posterior lateral right margin (LM6), posterior margin diagonal (right) to the sulcus (LM7), medial to the sulcus (LM8), posterior margin diagonal (left) to the sulcus (LM9), posterior lateral left margin (LM10), lateral left margin separated between 0.8 mm (LM11 and LM12), lateral left margin close to lateral eyes (LM13), anterior left lateral margin (LM14), left lateral eyes (LM15) and right lateral eyes (LM16).

Patella

Anterior distal margin (LM1), posterior distal margin separated between 0.5 mm (LM2 and LM3), posterior margin separated between 1.0 mm (LM4, LM5 and LM6), posterior basal margin separated between 1.0 mm (LM7, LM8 and LM10), anterior basal margin separated between 1.0 mm (LM10 and LM11), anterior margin close to the frst spine (LM12), anterior margin close to the second spine (LM13), anterior margin close to the fourth spine (LM14), anterior margin close to the ffith spine (LM15).

Morphometric analysis

From 105 confgurations matrix, the coordinates were aligned by generalized Procrustes analysis using tpsRelw software (Rohlf, 2016) to analyze sliding semilandmarks and extract the matrix confgurations (Partial Warps = PW) and centroid size (CS). The semilandmarks are thus allowed to slide along their curve or surface in order to remove the effects of the arbitrary spacing by "optimizing" the position of the semilandmarks regarding the average shape of the entire sample (Gunz & Mitteroecker, 2013). Later, CVAGen software (Sheets, 2010b) was used to perform a Canonical Variates Analysis (CVA) and Multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) to determine whether pre-defned groups (localities) can be statistically distinguished based on multivariate data. Finally, we analyzed the CS differences by means of ANOVA (P 0.05), with PAST statistical program (Hammer et al., 2001).

Coloration

The abdominals tergites and carapace color patterns were characterized with a Munsell letter color chart (Munsell, 2000). Four color categories were defned between the localities: Very Dark Brown (7.5YR 2.5 / 3), Black (7.5YR 2.5 / 1), Dark Brown (7.5YR 3/3), and Greenish Gray (Gray1 5 / 5G). Differences in coloration between specimens and localities were assessed using the chi-squared (X2) test, with PAST statistical program.

Carapace

Significant differences (ANOVA F=14.65, df 2/102, p < 0.001) between the CS and localities were found: El Roble (1.80 mm), Sincelejo (2.34 mm) and Colosó (2.47 mm). We present the CVA diagram (Fig. 2), MANOVA statistics and assignation test results, based on a priori group defnitions from localities, and a posteriori assignment based on Mahalanobis distances between each specimen and the locality mean. Axis 1 Λ = 0.1756, χ2 = 153.95, df 56, p < 0.0001 and Axis 2 Λ = 0.5055, χ2 = 60.38, df 27, p < 0.0001; the specimens were 80% correctly classifed: Colosó (78.3%), Sincelejo (76.4%) and El Roble (85.2%). The thin-plate spline deformation grid shows (Fig. 2) the differentiation between localities: The main differences occur in the posterior margin between LM6 to LM10, right lateral margin between LM4 and LM5, and anterior region between landmarks LM1 to LM3 and LM14.

Patella

Significant differences (ANOVA F=19.03, df 2/102, p < 0.001) between the CS and localities were found: El Roble (1.10 mm), Colosó (1.67 mm) and Slncelejo (1.68 mm). We dld not fnd significant differences between conformaron and localities (CVA/MANOVA p > 0.05).

Coloration

Significant variation of coloration between populations (X2=57.038 df=3 p<0.001) was registered. The colors that predominated according to the locality were: El Roble (66.67% dark brown), Colosó (48.65% black) and Sincelejo (58.82% brown very dark); only 2.85% specimens were greenish gray.

Intraspecific variation refers to the degree of differentiation that occurs between individuals of the same species, at a level of a single population or between isolated populations (Mayr, 1971). The displacement in the morphological features from a common and well-established phenotype, commonly occurs as a result of two processes (Salgado-Negret & Paz, 2015): a) phenotypic plasticity, that is to say, the emergence of different morphotypes that can express the same genotype in response to different conditions or b) by processes of local adaptation, involving genetic and phenotypic changes as a result of geographic isolation.

Our results about conformation and isometric size differences are consistent with those reported by Armas & Seiter (2013). These authors inform about the existence of a certain degree of phenotypic plasticity i n P. barbadensis, particularly a variation in the frontal area of the carapace. This variation was observed in the thinplate spline deformation grid (LM1-LM3 and LM14): The frontal area of the carapace in both Colosó and Sincelejo is partially delimited, whereas in El Roble is fully distinguished.

These fndings confrm that the prosoma is a very useful component in intraspecific and interspecific studies. Gasnier et al. (2002) studied the prosoma length variation of Ctenidae and Pisauridae spiders in relation to seasonality, and reported that spiders were smaller in October (season of low rainfall) in relation to other months. This variation was attributed to the differential availability of resources across the year. Bond & Beamer (2006) explored the mygalomorph spider carapace shapes in a phylogenetic context. These authors studied the prosoma conformation by means of two shape outline methods: semilandmarks and Fourier analysis. Recently, Bechara & Liria (2012) have described conformation and size differences in fve Buthidae and Scorpionidae species, and Fernández-Montraveta & Marugán-Lobón (2017) characterized the sexual variation in Donacosa merlini (Lycosidae). Both investigations used prosoma outline descriptors that combined landmarks type I and II with semilandmarks.

Fig. 1. Phrynus barbadensis carapace (A) and patella (B) showing the landmarks disposition. Black landmarks correspond to type I and II landmarks, while the gray correspond to semilandmarks.

Fig. 2. A. Canonical Variates Analysis carapace conformation diagram for 105 Phrynus barbadensis specimens in three Colombian localities (elipses encloses 95% of data); Colosó (black circles), Sincelejo (crosses) and El Roble (white rectangles). B. thin-plate splines deformation (as vectors) for CVA 1 and 2 axes.

On the other hand, the phenotypic differences in P. barbadensis could by attibuted to landcover characteristics. Colosó comprises dry forest relics, in contrast to those localities associated with transformed areas, like rural landscapes. El Roble is characterized by large areas dedicated to agriculture and livestock (Aguilera, 2005). Armas & Seiter (2013) consider that wide distribution of this species is associated to high adaptation to different habitats.

Finally, the color pattern differences could be the result of differential responses to the vegetation structure and soil use in the populations sampled. These results are consistent with those reported by Armas & Seiter (2013) and Miranda et al. (2014) on geographic variation in coloration of spider whip species. Amblypygids are cryptic animals of dark and brown colors (Armas, 2011; Wolff et al., 2015), therefore, the degree of pigmentation will be related to the substrate characteristics; populations in shaded locations will be darker than populations in open areas. Oxford & Gillespie (1998) have mentioned that the variation of color works as a thermoregulation mechanism because individuals in cold and humid environments tend to become darker than those in warm environments and with greater exposure to the sun; this is due to compensating the rate of uptake of solar radiation. It is believed that this factor may be infuencing equally in the populations studied.

As far as we know, this is a second investigation that performs a geometric morphometrics analysis in whip spiders. Miranda et al. (2014) have reviewed the taxonomy of T richodamon species, reported significant interspecific differences of shape and size among specimens of different genera (Damon, Euphrynichus, Phrynichus, and T richodamon), but not among T richodamon species. Our study represents a frst contribution to the intraspecific variation in whip spiders, and the results corroborate the value of geometric morphometrics for adaptive processes as well as suggest future investigations that correlated shape and size sexual dimorphism with environmental factors such as the substrate type, land cover, among others.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the entomology laboratory of the University of Sucre and Mr. Pedro Marquez for their logistical support. Also, we thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback to this paper.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA CITADA

- Aguilera, M. (2005). La economía del departamento de Sucre: Ganadería y sector público. Documentos de trabajo sobre economía regional. Banco de la República, Bogotá [ Links ]/

- Armas, L.F. (2011) Diversidad de Amblypygi en las Américas. En: Memorias y Resúmenes del III Congreso Latinoamericano de Aracnología, 2011, Montenegro, Quindío, Colombia. Pp. 35-42. [ Links ]

- Armas, L.F., & Seiter, M. (2013) Phrynus gervaisii (Pocock, 1894) is a junior synonym of Phrynus barbadensis (Pocock, 1893) (Amblypygi: Phrynidae). Revista Ibérica de Aracnología, 23: 128–132

- Bechara, W.Y., & Liria, J. (2012) Morfometría geométrica en cinco especies de Buthidae y Scorpionidae (Arachnida: Scorpiones) de Venezuela. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 83: 421-431. [ Links ]

- Bond J.E., & Beamer, D.A. (2006) A morphometric analysis of mygalomorph spider carapace shape and its efficacy as a phylogenetic character (Araneae). Invertebrate Systematics, 20: 1-7. [ Links ]

- Bookstein, F.L. (1991) Morphometric tools for landmark data: Geometry and biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

- Chiriví, D., & Armas, L.F. (2012) La subfamilia Phryninae (Amblypygi: Phrynidae) en Colombia. Boletín de la Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, 50: 395-402. [ Links ]

- Dunlop, J.A. (2002) Phylogeny of Chelicerata. Biodiversidad, taxonomía y biogeografía de artrópodos de México: Hacia una síntesis de su conocimiento. Vol. III (ed. Llorente Bousquets, J., & Morrone, J.J.), pp. 117-141. Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, México, D.F. [ Links ]

- Fernández-Montraveta, C., & Marugán-Lobón, J. (2017) Geometric morphometrics reveals sex-differential shape allometry in a spider. PeerJ, 5: e3617 [ Links ]

- Gasnier, T.R., de Azevedo, C.S., Torres-Sanchez, M.P., & Höfer, H. (2002) Adult size of eight hunting spider species in central Amazonia: temporal variations and sexual dimorphisms. Journal of Arachnology, 30(1): 146-154. [ Links ]

- Gunz, P., & Mitteroecker, P. (2013) Semilandmarks: a method for quantifying curves and surfaces. Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy, 24(1): 103–109.

- Hammer, Ø., Harper, D.A.T., & Ryan, P.D. (2001) PAST version 2.17: Paleontological Statistics software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4(1): 1-9.

- Mayr, E. (1971) Populations, Species and Evolution. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Abridged Ed., Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Miranda, G.S., De Leão Giupponi, A.P., & Kury, A.B. (2014) Taxonomic review of the Amblypygid genus Trichodamon Mello-Leito, 1935 (Amblypygi, Phrynichidae). En: Abstracts book of the XXVIII European Congress of Arachnology, Torino, Italy. Pp. 33.

- Munsell, A.H. (2000) Munsell soil color charts. Munsell Color. Oxford, G.S., & Gillespie, R.G. (1998) Evolution and ecology of spider coloration. Annual Review of Entomology, 43: 619–643.

- Rohlf, F.J. (2002) Geometric morphometrics and phylogeny. Morphology, Shape and Phylogeny, 175-193.

- Rohlf, F.J. (2015) tpsDig, digitize landmarks and outlines, version 2.22. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook.

- Rohlf, F.J. (2016) tpsRelw, digitize landmarks and outlines, version 1.65. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook.

- Salgado-Negret, B., & Paz, H. (2015) Escalando de los rasgos funcionales a procesos poblacionales, comunitarios y ecosistémicos. La ecología funcional como aproximación al estudio, manejo y conservación de la biodiversidad: protocolos y aplicaciones (ed. Salgado-Negret, B.), pp. 12-35. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, D. C., Colombia.

- Sheets, H.D. (2010a) MakeFan, a tool for drawing alignment “fans” at equal angular spacing. Disponible en: http://www3.canisius.edu/~sheets/imp7.htm

- Sheets, H.D. (2010b). TwoGroup, program for testing significant differences in shape between two groups. Disponible en: http://www3.canisius.edu/~sheets/imp7.htm

- Shultz, J.W. (1999) Muscular anatomy of a whip spider, Phrynus longipes (Pocock) (Arachnida: Amblypygi), and its evolutionary significance. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 126: 81-116.

- Toro, I.M.V., Manriquez, S.G., & Suazo, G.I. (2010) Morfometría geométrica y el estudio de las formas biológicas: de la morfología descriptiva a la morfología cuantitativa. International Journal of Morphology, 28(4): 977-990.

- Torres Contreras, R.A., de Armas, L.F., & Álvarez-García, D.M. (2015). Cannibalism in whip spiders (Arachnida: Amblypygi). Revista Ibérica de Aracnología, 26: 79-80.

- Weygoldt, P. (1998) Evolution and systematics of the Chelicerata. Experimental & Applied Acarology, 22(2): 63-79.

- Weygoldt, P . (2000) Whip spiders (Chelicerata: Amblypygi). Their biology, morphology and systematics. Apollo Books, Stenstrup, Denmark.

- Wheeler, W.C., & Hayashi, C.Y. (1998) The phylogeny of the extant chelicerate orders. Cladistics, 14(2): 173-192.

- Wolff, J.O., Seiter, M., & Gorb, S.N. (2015) Functional anatomy of the pretarsus in whip spiders (Arachnida, Amblypygi). Arthropod Structure & Development, 44(6): 524-540.