Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina

versión impresa ISSN 0373-5680versión On-line ISSN 1851-7471

Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. vol.78 no.3 La Plata set. 2019

Nota-Note

First record of domestic colonies of the dark chromatic variant of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae)

Primer registro de colonias domésticas de la variante cromática oscura de Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae)

LOBBIA, Patricia A.1,2,*, ALVAREZ, Rodrigo1, PICOLLO, María I.2,3 & MOUGABURE-CUETO, Gastón1,2

1 Laboratorio de Investigación en Triatominos (LIT), Centro de Referencia de Vectores (CeReVe), Programa Nacional de Chagas, Ministerio de Salud de la Nación. Hospital Colonia-Pabellón Rawson. Santa María de Punilla, Córdoba, Argentina. * E-mail: patalobbia@gmail.com

2 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). Argentina.

3 Centro de Investigaciones de Plagas e Insecticidas (CIPEIN), Unidad de Investigación y Desarrollo Estratégico para la Defensa (UNIDEF)/CONICET. Argentina.

Received 31 - I - 2019 | Accepted 12 - VI - 2019 | Published 26 - IX - 2019 https://doi.org/10.25085/rsea.780307

ABSTRACT. Triatoma infestans (Klug) is the main vector of Chagas disease in southern South America. Although this species shows a similar morphology and chromatic pattern throughout its geographical distribution, some melanic variations have been described. Most of these variants were recognized as part of wild populations constituting evidence of a wild distribution for T. infestansgreater than the expected. This paper reports the presence of eight adults and ffteen immature individuals of melanic T. infestansin domiciliary units of Argentine Gran Chaco. This is the frst report of domestic colonies of the dark chromatic morph of T. infestans.

KEYWORDS. Dark morph. Geographical variants. Triatominae.

RESUMEN. Triatoma infestans(Klug) es el principal vector de la enfermedad de Chagas en el sur de Sudamérica. Aunque esta especie muestra una morfología y un patrón cromático similar a través de su distribución geográfica, algunas variantes melánicas han sido descriptas. La mayoría de estas variantes fueron reconocidas como parte de poblaciones silvestres, que evidenció una distribución silvestre de T. infestansmayor a la esperada. Este trabajo informa la presencia de ocho adultos y quince individuos inmaduros de T. infestans melánicos en unidades domiciliarias en el Gran Chaco argentino. Este es el primer registro de colonias domésticas de la variante cromática oscura d e T. infestans.

PALABRAS CLAVE. Morfo oscuro. Triatominae. Variantes geográficas.

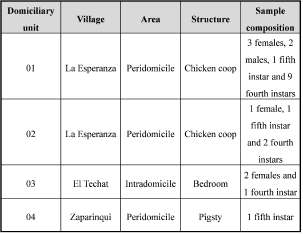

Triatoma infestans(Klug) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) is a haematophagous insect belonging to the subfamily Triatominae and is the main vector of Chagas disease in the Southern Cone of South America. Although several studies have reported the existence of sylvatic populations (Noireau, 2009), the habitat of this species is mainly human dwelling in rural zones of the endemic area (Lent & Wygodzinsky, 1979). Triatoma infestans shows a similar morphology and chromatic pattern throughout its geographical distribution. However, some particular morphs were described. According to their phenotypic features, these geographical variants can be grouped in a large morph and a melanic morph (Ceballos et al., 2009; Noireau, 2009). The frst of them was named "Mataral morph" and is represented by Andean sylvatic insects from Cochabamba department of Bolivia (Cortez et al., 2007). The dark chromatic variant is represented by samples collected from different non-Andean geographic locations very far from each other (i.e. Bolivian Chaco, Argentine Chaco, Paraguayan Chaco and Argentine Mesopotamia) (Martinez et al., 1987; Noireau et al., 1997; Yeo et al., 2005; Ceballos et al., 2009). Most of these morphs were recognized as members of the species as part of wild populations, constituting evidence of a wild distribution greater than expected (Bargues et al., 2006; Noireau, 2009; Piccinali et al., 2011). A particular case is the melanic form found in the north-east of Argentina. This insect was originally described as a subspecies of T. infestans and later it was raised to the rank of species as T. melanosoma (Martinez et al., 1987; Lent et al., 1994), although at present it is considered a geographical variation of T. infestans (Bargues et al., 2006). The Gran Chaco ecoregion, and in the humid forest of the Argentine province of Misiones (Martinez et al., 1987; Noireau et al., 1997, 2000; Ceballos et al., 2009). The Gran Chaco specimens were collected in wild ecotopes and there were evidences of wild populations of T. infestans (Noireau et al., 1997; Ceballos et al., 2009). The habitat of the specimens collected in Misiones is less certain. The authors reported that the insects were collected in peridomiciliary habitats near chicken coops without any specification of the exact place where they had been found (Martinez et al., 1987). Therefore, it is not clear if those insects were in a structure of anthropic origin (e.g.: coops, corrals, etc.) or in a non-artificial structure (e.g.: trees, birds' nests, etc.). Thus, the present paper reports for the frst time the occurrence of a chromatic morph of T. infestans in a domestic or anthropic structure within a domiciliary unit.

Although the dark coloration is the common characteristic of all chromatic morphs of T. infestans, the chromatic pattern is not the same. Specimens collected in Misiones presented a general black coloration with the exception of a clearer medial zone of the sternites and, in the connexivum, a fne yellowish line in the anterior edge of each segment (Martinez et al., 1987). On the other hand, insects of the Gran Chaco showed an overall darker coloration and smaller yellow spots in the connexivum than T. infestans with typical coloration, and yellow/orange spots in the posterior coxae which are dark brown or black in the typical specimens (Noireau et al., 1997; Ceballos et al., 2009). Although Martinez et al. (1987) highlighted the black color of the coxae, the connexivum and the proximal part of the femora of Misiones morph, authors who described the insects of the Gran Chaco did not refer to color of the base of the femora. In any case, the dark morph of the Gran Chaco was interpreted as an intermediate chromatic variant between a typical T. infestans and a darkest morph of Misiones (Noireau et al., 1997; Catalá & Torres, 2001). The insect here described showed a general black coloration with small yellow/orange spots in the connexivum and the proximal part of femora and trochanters also yellow/orange. Thus, considering the chromatic pattern of each variant, the insects reported in this work would belong to the variant previously found in the Gran Chaco (although they differ in the color of the posterior coxae), differing from those found in Misiones (differentiation based on the color of the base of the femora).

Fig. 1. External appearance of the male of Triatoma infestans. A. typical chromatic pattern; B. dark chromatic pattern Bar scale = 5 mm

Fig. 2. External appearance of the female of Triatoma infestans. A. typical chromatic pattern; B. dark chromatic pattern Bar scale = 5 mm

Melanic morphs of T. infestans were historically associated to sylvatic populations (Ceballos et al., 2009; Noireau, 2009). In this context, one question had special attention: What is the potential of these wild populations to colonize the domestic environment? Before addressing this question, it is necessary to establish if the insects reported in this work have colonized the domestic environment from the wild habitat, or if they are domestic insects. It is the frst time that this morph has been collected in human dwellings. However, these houses are in an area with relatively high frequency of entomological monitoring due to the existence of populations with a very high resistance (Mougabure-Cueto & Picollo, 2015). If these insects were domestic, they should have been detected before and repeatedly. On the other hand, Ceballos et al. (2009) reported dark sylvatic T. infestans in a department of the province of Chaco, location of the villages in which the insects reported in this work were collected. In this way, it is highly probable that these insects came from the wild environment. Thus, this research shows that the melanic T. infestans can colonize the human dwelling. Considering that the melanic T. infestans probably belong to sylvatic populations, this paper shows that the sylvatic T. infestans probably colonize the domiciliary environment.

Colonization occurs due to the dispersal of individuals to areas where the species is not established or was displaced (e.g.: by control actions) (Schofeld, 1994). Dispersal in triatomines can be passive (e.g.: in the clothes, feathers, or hair) or active (by fight of the adults or walk). Passive dispersal has a relevant role in the explanations of the spread of T. infestans from its center of origin as species and also of current dispersive events (Cortez et al., 2010; Faúndez, 2016). Active dispersal was associated to search for food, shelter or couple, and is considered one of the main mechanisms of colonization and/or re-infestation of human dwellings (Schofeld et al., 1992; Vazquez-Porkopec et al., 2004). Dispersal by fight has received the most attention in triatomines (Schofeld et al., 1992; McEwen et al., 1993; Vazquez-Prokopec et al., 2004). However, in recent years, some studies showed the relevance of walking dispersal in T. infestans and suggested its advantage for colonization by allowing the displacement of individuals with high nutritional status and with ovulated eggs (Abrahan et al., 2011; Lobbia et al., 2019a, b). Thus, displacement of T. infestans between sylvatic and domestic areas and subsequent colonization may be events more frequent than assumed. Recently, Carbajal-de-la-Fuente et al. (2019) reported the presence of a male of T. infestans in a sylvatic environment of the Argentine Monte ecoregion and the dispersal from a dwelling would be the most likely explanation since a house very infested with T. infestans was within the fight range of this species. More studies are needed to determine the geographical distribution of the dark morph and wild foci of T. infestans in Argentina and the relevance of the exchange of individuals between both wild and domestic environments in T. infestans.

We thank the technicians of the Coordinación Nacional de Control de Vectores (Ministerio de Salud de la República Argentina) and of the Programa de Chagas (Ministerio de la Salud Pública de la Provincia del Chaco). This study received fnancial support from Agencia Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (Argentina) (ANPCyT) (PICT 2015-1905), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Argentina) (CONICET), and Proyecto de Fortalecimiento de la Interrupción de la Transmisión Vectorial de la Enfermedad de Chagas en la República Argentina- Fonplata ARG 19/2013, Ministerio de la Salud de la República Argentina.

Abrahan, L.B., Gorla, D.E., & Catalá, S.S. (2011) Dispersal of Triatoma infestansand other Triatominae species in the arid Chaco of Argentina-fying, walking or passive carriage? The importance of walking females. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 106, 232-239. [ Links ]

Bargues, M.D., Klisiowicz, D.R., Panzera, F., Noireau, F., Marcilla, A., Perez, R., Cortez, M.R., O'Connor, J.E., Gonzáles-Candelas, F., et al. (2006) Origin and phylogeography of the Chagas disease main vector Triatoma infestansbased on nuclear rDNA sequences and genome size. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 6, 46-62. [ Links ]

Carbajal-de-la-Fuente, A.L., del Pilar Fernández, M., Piccinali, R.V., Rodríguez-Planes, L.I., Duarte, R., & Gürtler, R.E. (2019) Occurrence of domestic and intrusive triatomines (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in sylvatic habitats of the temperate Monte Desert ecoregion of Argentina. Acta tropica, 196, 37-41. [ Links ]

Catalá, S., & Torres, M. (2001) Similarity of the patterns of sensilla on the antennae of Triatoma melanosoma and Triatoma infestans. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, 95, 287-295. [ Links ]

Ceballos, L.A., Piccinali, R.V., Berkunsky, I., Kitron, U., & Gürtler, R.E. (2009) First fnding of melanic sylvatic Triatoma infestans(Hemiptera: Reduviidae) colonies in the Argentine Chaco. Journal of Medical Entomology, 46, 1195-1202. [ Links ]

Cortez, M.R., Emperaire, L., Piccinali, R.V., Gürtler, R.E., Torrico, F., Jansen, A.M., & Noireau, F. (2007) Sylvatic Triatoma infestans(Reduviidae, Triatominae) in the Andean valleys of Bolivia. Acta Tropica, 102, 47-54. [ Links ]

Cortez, M.R., Monteiro, F.A., & Noireau, F. (2010) New insights on the spread of Triatoma infestansfrom Bolivia-Implications for Chagas disease emergence in the Southern Cone. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 10, 350-353. [ Links ]

Faúndez, E.I. (2016) Sobre los registros aislados de Triatoma infestans (Klug, 1834) (Heteroptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) en el sur de Chile. Arquivos Entomolóxicos, 15, 121-124. [ Links ]

Lent, H., & Wygodzinsky, P. (1979) Revision of the Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) and their significance as vectors of Chagas disease. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 163, 123-520. [ Links ]

Lent, H., Jurberg, J., Galvão, C., & Carcavallo, R.U. (1994) Triatoma melanosoma, new status for Triatoma infestans melanosoma Martinez, Olmedo & Carcavallo, 1987 (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 89, 353-358.

Lobbia, P.A., Rodríguez, C., & Mougabure-Cueto, G. (2019a) Effect of nutritional state and dispersal on the reproductive efficiency in Triatoma infestans (Klug, 1834) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) susceptible and resistant to deltamethrin. Acta Tropica, 191, 228-238.

Lobbia, P. A., Rodríguez, C., & Mougabure-Cueto, G. (2019b) Effect of reproductive state on active dispersal in Triatoma infestans(Klug, 1834) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae) susceptible and resistant to deltamethrin. Acta tropica, 196, 7-14.

Martinez, A., Olmedo, R.A., & Carcavallo, R.U. (1987) Una nueva subespecie Argentina deTriatoma infestans. Chagas, 4, 7-8.

McEwen, P., Lehane, M., & Whitaker, Ň.C. (1993) The effect of adult population density on fight initation in Triatoma infestans(Klug) (Hemiptera: Reduviidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 116, 321-325.

Mougabure-Cueto, G., & Picollo, M.I. (2015) Insecticide resistance in vector Chagas disease: evolution, mechanisms and management. Acta Tropica, 149, 70-85.

Noireau, F. (2009) Wild Triatoma infestans, a potential threat that needs to be monitored. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 104, 60-64.

Noireau, F., Flores, R., Gutierrez, T., & Dujardin, J.P. (1997) Detection of wild dark morphs of Triatoma infestans in the Bolivian Chaco. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 92, 583-584.

Noireau, F ., Flores, R., Gutierrez, T., Abad-Franch, F ., Flores, E., & Vargas, F. (2000) Natural ecotopes of Triatoma infestans dark morph and other wild triatomines in the Bolivian Chaco. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 94, 23-27.

Piccinali, R.V., Marcet, P.L., Ceballos, L.A., Kitron, U., Gürtler, R.E., & Dotson, E.M. (2011) Genetic variability, phylogenetic relationships and gene fow in Triatoma infestans dark morphs from the Argentinean Chaco. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 115, 895-903.

Schofeld, C.J. (1994) Triatominae: Biology&Control. Eurocommunica Publications, Bognor Regis, UK.

Schofeld, C.J., Lehane, M.J., McEwen, P., Catalá, S.S., & Gorla, D.E. (1992) Dispersive fight by Triatoma infestans under natural climatic conditions in Argentina. Medical Veterinary Entomology, 6, 51-56.

Vazquez-Prokopec, G.M., Ceballos, L.A., Kitron, U., & Gürtler, R.E. (2004) Active dispersal of natural populations of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in rural northwestern Argentina. Journal of Medical Entomology, 41(4), 614-621.

World Health Organization (WHO) (1994) Protocolo de evaluación del efecto insecticida sobre triatominos. Acta Toxicológica Argentina, 2, 29-32.

Yeo, M., Acosta, N., Llewellyn, M., Sánchez, H., Adamson, S., Miles, G.A.J., López, E., González, N., Patterson, J.S., et al. (2005) Origins of Chagas disease: Didelphis species are natural hosts of T rypanosoma cruzi I and armadillos hosts of T rypanosoma cruzi II, including hybrids. International Journal for Parasitology, 35, 225-233.