Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Serie correlación geológica

versión On-line ISSN 1666-9479

Ser. correl. geol. vol.35 no.2 San Miguel de Tucumán dic. 2019

ARTICULOS

Geochemical characterization of the gneisses and schists in Ekumtak area: further evidence for a metasedimentary protolith and moderate weathering intensity for the Precambrian Basement complex of Nigeria

Caracterización Geoquímica De Gneis Y Esquistos En El Area De Ekumtak: Más Evidencia De Un Protolito Metasedimentario Y Una Intensidad De Meteorizaciónmoderada Para El Complejo Del Sótano Precámbrico De Nigeria.

Chinedu Uduma IBE1

1Department of Geology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 410001, Nigeria. Corresponding author: chinedu.ibe@unn. edu.ng. +234 813 8655 078

Abstract: The study area is characterized by migmatitic banded gneisses and garnet mica schists. These rocks are associated with amphibolite and granitic intrusions. These migmatitic gneisses and schists are characterized by paragenetic mineral assemblages that reflect an evolutionary history that involved processes of sedimentation and upper amphibolite facies metamorphism. Geochemical data show that the rocks are silica rich with moderate to elevated concentrations of Al2O3 which is consistent with pelitic rocks. The gneisses show positive anomalies in Rb, K, Th, La, Sm and strong negative anomalies in Ta, Nb, Sr, Ti, Tm, Yb, Zr and Y with an overall enrichment of the large ion lithophile elements (LILE: K, Ba and Rb) and depletion of the high field strength elements (HFSE: Zr, Ti and Y). Specifically, the Eu-anomalies, expressed as (Eu/Eu*) range from 0.03 to 1.4 in the gneisses and from 0.09 to 1.1 in the schists. LaN/YbN ratios are from 7 to 93 for the gneisses and 1.9 to 46.4 for the schist. These values suggest that the protoliths of these metasedimentary rocks are predominantly shales, greywackes and arkosic sandstones with surbodinate basic to intermedíate volcanic components. Their chemical index of alteration values ranges from 57.7-71.7 in the gneisses and 66.6-74.9 in the schists with mean of 68% and standard deviation of ±3.4 suggesting a recycle process and relatively moderate chemical weathering of the protoliths. The metasedimentary origin for the rocks is consistent with results from other parts of the Nigerian Precambrian Basement complex.

Key words: Gneisses, Metamorphism, Protolith, Precambrian, Metasedimentary, Schists.

Resumen: El área de estudio se caracteriza por gneis con bandas migmatíticas y esquistos de mica granate. Estas rocas están asociadas con intrusiones graníticas y anfibolíticas. Estos gneis y esquistos migmatíticos se caracterizan por conjuntos de minerales paragenéticos que reflejan una historia evolutiva que involucró procesos de sedimentación y metamorfismo de facies de anfibolitas superiores. Los datos geoquímicos muestran que las rocas son ricas en sílice con concentraciones moderadas a elevadas de Al2O3, lo que es consistente con las rocas pelíticas. Los gneises muestran anomalías positivas en Rb, K, Th, La, Sm y fuertes anomalías negativas en Ta, Nb, Sr, Ti, Tm, Yb, Zr e Y con un enriquecimiento general de los elementos litófilos de iones grandes (LILE: K, Ba y Rb) y el agotamiento de los elementos de alta intensidad de campo (HFSE: Zr, Ti e Y). Específicamente, las Eu-anomalías, expresadas como (Eu / Eu *) varían de 0.03 a 1.4 en los gneises y de 0.09 a 1.1 en los esquistos. Las relaciones LaN / YbN son de 7 a 93 para los gneises y de 1,9 a 46,4 para el esquisto. Estos valores sugieren que los protolitos de estas rocas metasedimentarias son predominantemente lutitas, grauvacas y areniscas arkósicas con componentes volcánicos surbodinados básicos a intermedios. Su índice químico de valores de alteración varía de 57.7 a 71.7 en los gneises y 66.6 a 74.9 en los esquistos con una media de 68% y una desviación estándar de ± 3.4, lo que sugiere un proceso de reciclaje y una meteorización química relativamente moderada de los protolitos. El origen metasedimentario de las rocas es consistente con los resultados de otras partes del complejo del Sótano Precámbrico de Nigeria.

Palabras clave: Gneis, Metamorfismo, Protolito, Precámbrico, Metasedimentario, Esquistos.

Introduction

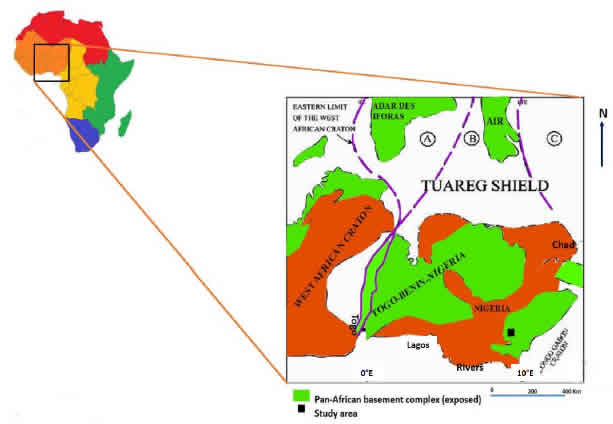

The oldest basement rocks (ca. 3500 Ma) in West Africa are found at the southeastern border of the West African craton (Kroner et al, 2001) (Figure 1). The West African terra-ne was affected by the Eburnean orogeny (ca. 2000 ± 150 Ma) and consolidated as a craton during a period of tectonic quiescence between 1700 to 1000 Ma (Liegeois etal, 2013).

Extensional events which were associa-ted with continental break up affected the West African craton in the early Neoproterozoic (Liegeois et al, 2013). These favored passive margin sedimentation with localized calc-alka-line volcanic occurrences and the development of younger basement rocks, represented by pe-litic to psammitic terranes (Kinnaird, 1984).

During the Gondwana assembly, the West African craton (WAC) was subjected to convergence along its boundaries (Kinnaird, 1984). The eastern passive margin collided with the active margin of the Trans Saha-ran orogenic belt (TSOB) of which the Ni-gerian Precambrian Basement Complex is a part and lies between the WAC and the Con-go-Gabon craton (Figure 1). The collision at this plate margin is believed to have led to the reactivation and remobilization of the internal region of the Pan-African belt and the Nigerian Precambrian Basement Complex (Ibe and Obiora, 2019).

Figure 1. Location of the Precambrian Basement Complex in Nigeria between the West African craton, the Con-go-Gabon craton and the southern part of the Tuareg shield./Figura 1. Ubicación del complejo del sótano Precámbrico en Nigeria entre el cratón de África occidental, el cratón Congo-Gabón y la parte sur del escudo Tuareg.

Geological setting

The study area is located within the extensión of the Bamenda highlands of Ca-meroun into southeastern Nigeria, otherwise referred to as the Bamenda massif or the southeastern Nigerian Precambrian Base-ment Complex (Obiora, 2006). The migmatitic rocks in the area were grouped together as "Granitoids" on the Geological Map of Nigeria produced by the Nigerian Geological Survey Agency (NGSA, 2011). The migmati-tic character of the rocks reflects long, protracted and possibly polycyclic evolutionary history (Annor, 1998), which corroborates the four thermotectonic events that have affected the Nigerian Basement at various localities (Burke and Dewey, 1972). The present study was carried out because of the need for the mapping and delineation of the various rock types of the different units of the Precambrian Basement Complex in the area. It was also carried out because of the need for detailed petrographic and geochemical (ma-jor-, trace-, and rare-earth elements) studies on the migmatitic rocks and granitoids for proper assessment of their protoliths as well as their weathering history.

Field relationship and petrographic characteristics of the rocks

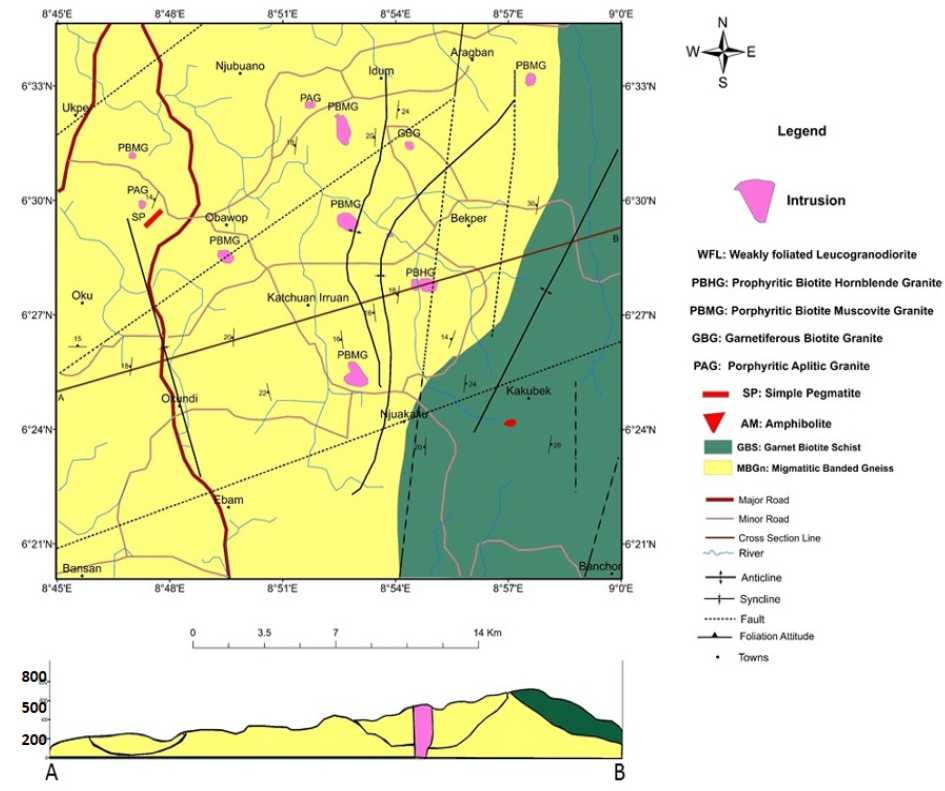

The study area is characterized by mig-matitic banded gneisses and garnet biotite schists. The gneisses constitute the Basement in strict sense and are either overlain or intruded by the other units. They generally have NNW-SSE trending gneissose foliation with few N-S trends and dip values which vary from as low as 10o to 35o in both NE and SW directions (Figure 2). The modal compositions of the rocks are presented in Table 1.

Garnet-Biotite Schist (GBS)

This unit occurs in the eastern part of

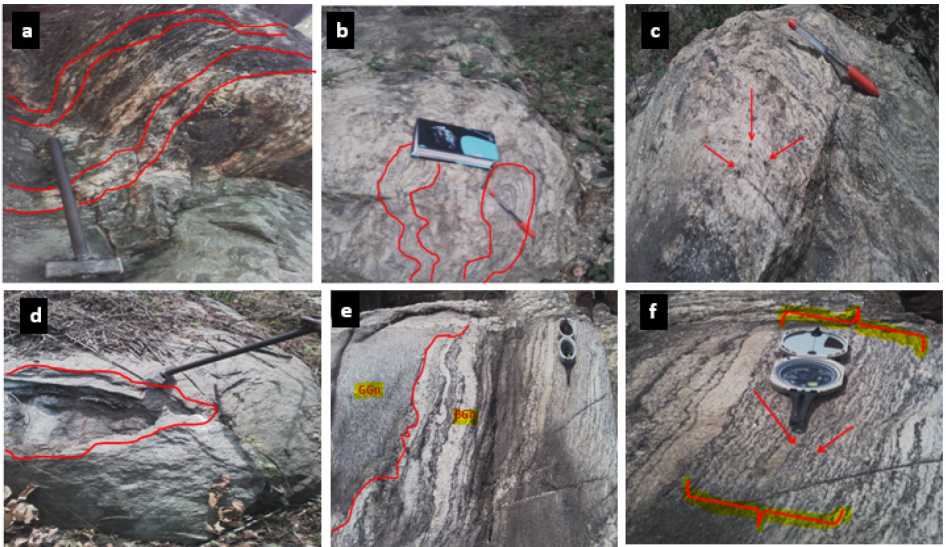

the study area (Figure 2) and extends outsi-de the map area to the eastern corner of the Kyikabe hills. It constitutes about 30% of the exposed rocks in the study area. The rock is medium grained, melanocratic and characteri-zed by schistose foliation defined by the prefe-rential alignment of the black-colored mineral (biotite). It also contains quartz and garnet. They are conspicuously melanocratic due to the preponderance of biotite in the rock. The exposure at Njuakaku hill is characterized by intense micro-folding of quartz-feldspar injec-tions and ptygmatic folds (Figure 3a). Schisto-sity in most of the outcrops trends NW-SE to NE-SW

Migmatitic banded gneiss (MBGn)

This unit occurs in the western part of the study area. It is generally mesocratic, coarse grained and shows a well-defined gneissose foliation consisting of alternations of light-colo-red layers containing feldspars and quartz with dark colored layers containing biotite. The gneissose foliation trends essentially NNW-SSE and N-S with dips of 15 to 30o to the east and west. It possesses some qualities of mig-matites such as the occurrence of mixtures of different rock types with quartz-feldspar ve-ins. Generally, the migmatitic banded gneisses comprise both metamorphic host rock (paleo-some) and leucocratic acid injections (leuco-some). The leucosome commonly form layers or elongate thin lenses that are often concor-dant to the foliation of the paleosome giving the rock a banded appearance (Figure 3b). This unit also extends from the central to the southwestern parts of the area of study, stret-ching from Oku towards the south of Okundi, where it is characterized by porphyroblasts of garnet, feldspars and quartz which occasionally distort the gneissose foliation (Figure 3c). The exposure in Ekumtak hill is intensely exfoliated (Figure 3d). At Odajie-Mbube, which is located at about 9 km, northeast of Obawop, this unit is characterized by porphyroblasts of gar-net, biotite and feldspars in a coarse-grained groundmass of same minerals with sillimanite which was identified, particularly as stringers concentrated in the biotite-rich parts of the rock.

Figure 2. Geologic map of the study area./Figura 2. Mapa geológico del área de estudio.

Microscopic study

The minerals identified in the garnet biotite schists include quartz, andesine, garnet and muscovite. Some accessories include zircon and chlorite. In thin section, the schis-tose foliation is defined by the platy mineral, biotite. Other minerals that make up the rock include almandine garnet, quartz, microcline and plagioclase of An39 which is Andesine. For the banded gneisses, the melanocra-tic layers consist mainly of biotite, which is arranged in a parallel to sub-parallel manner (Figure 4a). The light-coloured layers, on the other hand contain feldspar, and quartz, with tiny specks of muscovite. Plagioclase occurs in crystals of two different compositions from anorthite composition determination, viz: An8 and An55, which are albite and la-bradorite, respectively (Figure 4b). The out-crops around Katchuan contains hornblende and sphene in addition. Sphene, as shown in thin section, has a high relief and occurs in euhedral crystals that have an acute rhom-bic cross section (Figure 4c). Hornblende measures about 3 mm and occurs in subido-blastic grains with inclusions of quartz and biotite (Figure 4d). Sillimanite is brown and occurs as fibrolite and small prismatic need-les closely associated with biotite in sillima-nite-biotite bands (Figure 4e). The growth of the porphyroblasts of garnet which me-asure about 8 mm in diameter and contains inclusions of quartz, biotite and opaque minerals, is accompanied by volume increase and the pushing away of the crystals of quartz and biotite while most of the biotite crystals around the porphyroblasts seem to have been eaten up by the formation of the garnet (Figure 4f). Some plagioclase crystals also show combined albite-carlsbad twinning while some have been sericitized such that their characteristic albite twinning have been almost obliterated (Figure 4g). Myrmekitic intergrowths are also observed in the rock (Figure 4h). The texture of garnet is poiki-loblastic as it is riddled with inclusions of quartz and hematite (Figure 4i).

| Table 1. Modal compositions of Precambrian Basement Gneisses (Gn 1-7) and Schists (Sh 1-6) of Bamenda massif, southeast of Ogoja, Southeastern Nigeria. | |||||||||||||

| Mineral | Gn1 | Gn2 | Gn3 | Gn4 | Gn5 | Gn6 | Gn7 | Sh1 | Sh2 | Sh3 | Sh4 | Sh5 | Sh6 |

| Quartz | 20 | 20 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 25 | 30 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 |

| Plagioclase | 10 | 30 | 10 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 10 |

| Microcline | 5 | <1 | <1 | 5 | 5 | <1 | 5 | 10 | 5 | <1 | <1 | 5 | 5 |

| Biotite | 30 | 25 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 15 | 25 |

| Garnet | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 15 | 30 | <1 | <1 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 25 |

| Muscovite | 10 | 5 | <1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | <1 | <1 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 |

| Hornblende | <1 | 5 | <1 | 20 | 10 | <1 | 25 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Cordierite | 10 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Sillimanite | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 10 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Sphene | <1 | <1 | 20 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Zircon | 5 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | <1 | <1 | 5 |

| Chlorite | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 5 | <1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | <1 |

| Sericite | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | <1 | 5 | 10 | 10 | <1 | 5 | 5 | <1 | <1 |

| Opaque | <1 | <1 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 5 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 1. Modal compositions of Precambrian Basement Gneisses and Schists of Bamenda massif, southeast of Ogoja, Southeastern Nigeria./Tabla 1. Composiciones modales degneisesy esquistos del sótano Precámbrico del macizo de Bamenda, al sureste de Ogoja, sureste de Nigeria.

Figure 3. Field photographs./Figura 3. Fotografías de campo.

Figure 4. Photomicrograph of MBGn and GBS./Figura 4. Microfotografía de MBGn y GBS.

Geochemistry

Twenty-eight (28) fresh representative samples consisting of twenty-two (22) migma-titic banded gneiss (MBGn) and Six (6) gar-net-biotite schist (GBS) were selected for geo-chemical analyses.

Analytical procedure

The samples were crushed in a jaw crus-her at the Inorganic Geochemistry Research Laboratory of the Department of Geology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The crushed samples were pulverized in a Vibrating Disc Mill. Final size reduction, mixing and homoge-nization to < 75pm were done with a Mixer Mill. One hundred gram (100 g) of each sample were thereafter packaged and dispatched to Bureau Veritas Minerals Pty Ltd, Canning Vale, Perth, Western Australia for major element oxides and trace element geochemistry using X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Inductively Coupled Mass

Spectrometer (ICP-MS), respectively. Details of the analytical procedure are in Ibe and Obiora (2019).

Geochemical composition

Major Elements

The major element oxides data and CIPW norms on the rocks are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

The gneisses (MBGn) have values of SiO2 in the range of 57.10 to 73.84% with a mean value of 67.44%. They contain moderate Al2O3(13.30-16.60%), low TiO2 (0.10- 1.15%), MgO (0.06-3.57%) and MnO (0.03- 0.14%) as well as high K2O (0.95- 5.08%), Na2O (2.18-6.69%) and CaO (0.28- 8.26 %). The Fe-number (Total Fe) ranges from 3.96 to 13.4 with enrich-ment in alumina (12.3 to 17.1 %). The TiO2/ Al2O3 ratio values of about 0.01-0.09, appear to be moderately high and have been given various interpretations. Goldschmidt (1954) reported that TiO2/ Al2O3 ratio of about 0.04% is indi-cative of the presence of clayey components in rocks while Spear and Kanaris-Sotirious (1976) suggested that the same ratio is indicative of sediments contaminated by basic to intermedíate volcanic components. They are generally quartz, K-feldspar, albite, anorthite, hypersthe-ne and corundum normative.

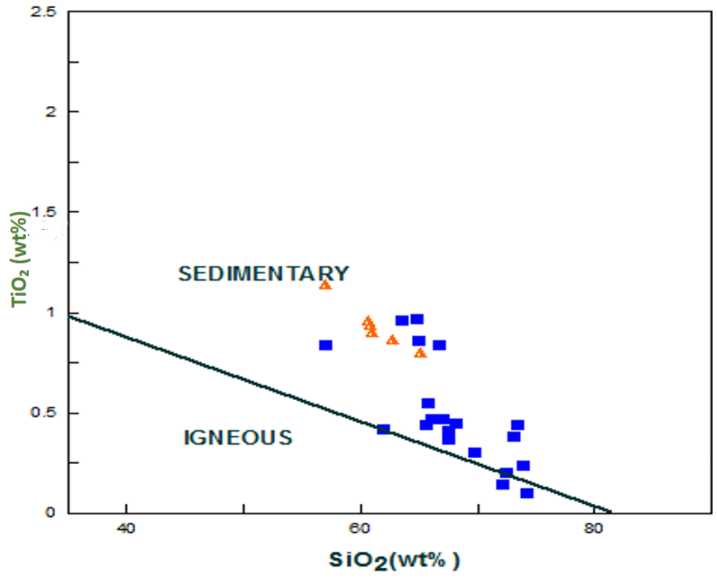

The schist (GBS) has moderate alumina to alkali (Al2O3/K2O+Na2O) ratios (2.31 to 3.85 %), low MgO (3.56 to 5.91 %) and CaO (0.74 to 2.92 %) contents, with MgO exceeding CaO. Contents of K2O are gene-rally greater than those of Na2O except in few cases (Table 3). The rocks plotted on the sedimentary field on the diagram of Tarney (1977) (Figure 5) which discriminates between sedimentary and igneous protoliths of meta-morphic rocks.

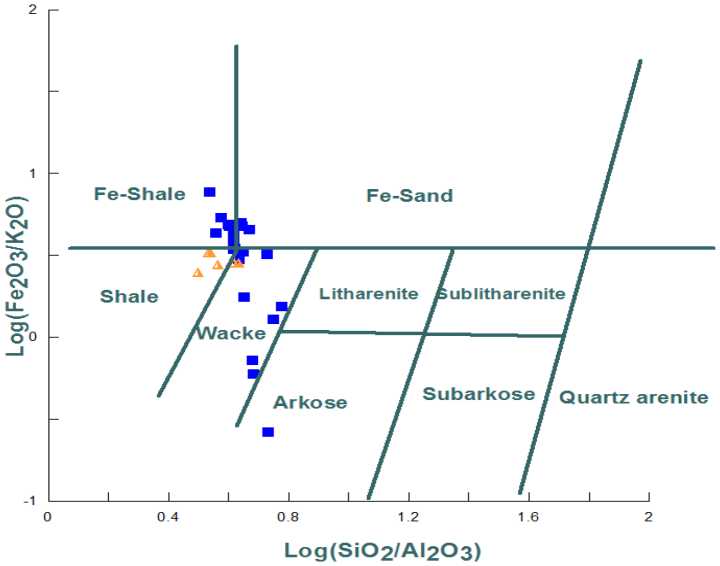

Further discrimination of the sedimentary protolith of the gneisses and schists was done by the plot of log (Fe2O3(t)/K2O) vs log (SiO2/Al2O3) after Herron (1988) (Figure 6) was utilized.

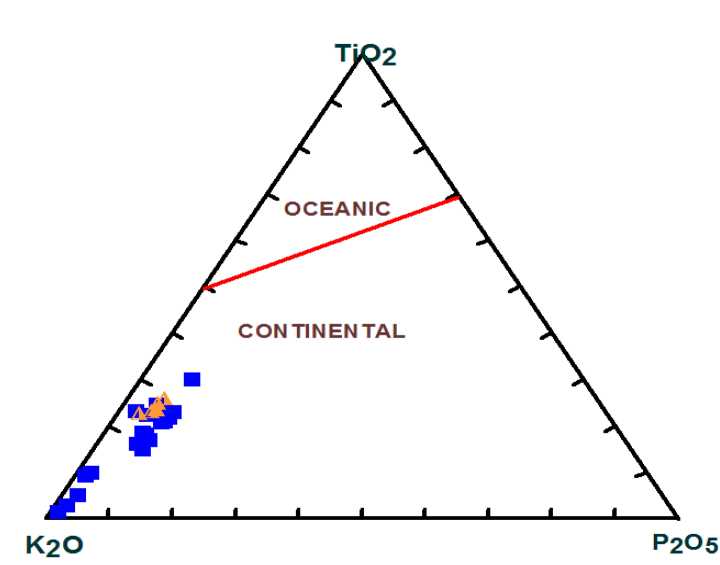

The gneisses plot in the Fe-shale, Fe-sand and greywacke and arkose regions whereas the schists plot in the shale and greywacke regions. They plot on the continental field on the crustal discrimination diagram of Pearce et al. (1984) (Figure 7).

Trace Elements

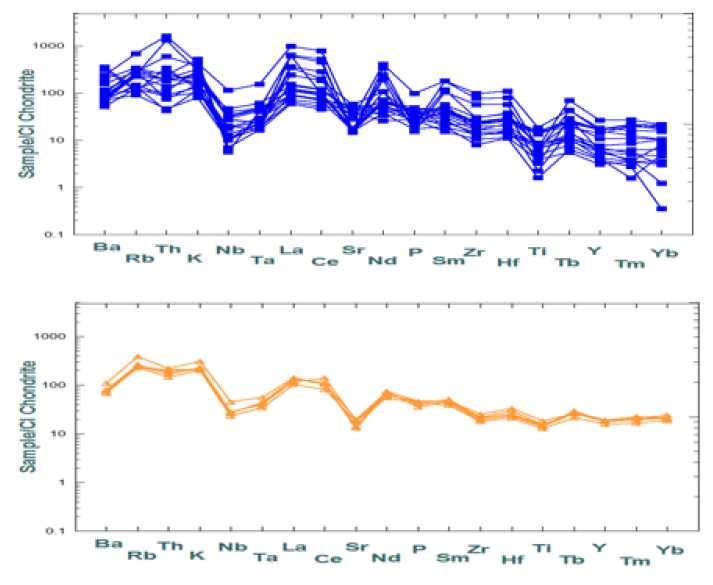

The trace elements compositions (ppm) of the rocks are presented in Table 4 and 5. Trace element distribution patterns for the migma-titic banded gneiss and garnetmica schist from the study area have been normalized to chondrites after Thompson (1982) and plot-ted as spidergrams (Figure 8). They show an overall enrichment of the large ion lithophile elements (LILE: K, Ba and Rb) and depletion of the high field strength elements (HFSE: Zr, Ti, Nb, Hf, Ta and Y). HFS concentra-tions are mainly controlled by the chemistry of the source and the crystal/melt processes that took place during the evolution of the rock.

Table 2. Major element oxide (wt %) compositions and CIPW norm valúes of the gneisses around Njuakaku, southeast of Ogoja./Tabla 2. Composiciones de óxido de elemento principal (% en peso)y valores normativos CIPW de los gneises alrededor de Njuakaku, al sureste de Ogoja.

| MBGnl | MBGn2 | MBGn3 | MBGn4 | MBGn5 | MBGn6 | MBGn7 | MBGn8 | MBGn9 | MBGnlO | MBGnll | |

| SiO2 | 66.19 | 67.56 | 61.93 | 73.84 | 65.55 | 57.10 | 66.10 | 65.73 | 67.09 | 69.69 | 67.52 |

| TiO2 | 1.15 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| Al2O3 | 14.80 | 16.4 | 16.50 | 13.80 | 15.30 | 16.60 | 16.00 | 15.80 | 15.20 | 15.90 | 17.00 |

| Fe2O3 | 5.02 | 3.56 | 4.88 | 2.32 | 4.48 | 7.61 | 4.44 | 4.79 | 4.65 | 2.81 | 3.20 |

| FeO | 3.95 | 2.71 | 2.75 | 1.64 | 1.78 | 5.79 | 3.04 | 3.13 | 2.98 | 1.94 | 2.16 |

| MnO | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| MgO | 0.06 | 1.48 | 2.15 | 1.04 | 2.95 | 3.57 | 2.18 | 2.30 | 2.32 | 1.42 | 1.12 |

| CaO | 2.54 | 0.38 | 5.03 | 2.94 | 4.67 | 8.26 | 4.33 | 4.17 | 4.38 | 3.68 | 4.63 |

| Na2O | 3.01 | 4.62 | 4.42 | 3.75 | 3.89 | 2.41 | 3.82 | 3.62 | 3.67 | 6.69 | 4.06 |

| K2O | 5.08 | 1.82 | 1.42 | 1.24 | 2.11 | 1.73 | 1.92 | 2.27 | 1.61 | 0.95 | 1.10 |

| P2O5 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| LOI | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.03 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 0.46 |

| Total | 102.68 | 99.53 | 100.09 | 101.23 | 101.76 | 105.29 | 102.52 | 102.63 | 102.86 | 103.90 | 101.81 |

| A | 8.09 | 6.44 | 5.84 | 4.99 | 6.00 | 4.14 | 5.74 | 5.89 | 5.28 | 7.64 | 5.16 |

| Fe* | 8.97 | 6.27 | 7.63 | 3.96 | 6.26 | 13.40 | 7.48 | 7.92 | 7.63 | 4.75 | 5.36 |

| Log F/K | -0.005 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.46 |

| S/A | 4.47 | 4.12 | 3.75 | 5.35 | 4.28 | 3.44 | 4.13 | 4.16 | 4.41 | 4.38 | 3.97 |

| Log S/A | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.60 |

| P2O5/TÍO2 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| MgO/CaO | 0.02 | 3.89 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.24 |

| CIPW Norm valúes | |||||||||||

| Q | 24.30 | 30.50 | 17.60 | 39.30 | 22.70 | 14.80 | 23.80 | 23.60 | 26.70 | 18.47 | 28.00 |

| Or | 29.80 | 10.70 | 8.30 | 7.30 | 12.40 | 10.20 | 11.30 | 13.30 | 9.50 | 5.60 | 6.50 |

| Ab | 25.20 | 38.80 | 37.00 | 31.50 | 32.60 | 20.17 | 32.00 | 30.30 | 30.80 | 56.10 | 34.10 |

| An | 9.60 | 0.70 | 20.90 | 13.74 | 18.00 | 29.20 | 20.40 | 19.30 | 20.20 | 10.50 | 21.96 |

| C | 0.80 | 6.60 | 1.24 | 8.00 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 1.10 | ||||

| Di wo | - | - | 1.00 | - | 1.06 | - | - | - | - | 2.00 | - |

Table 2: Continued

| MBGnl | MBGn2 | MBGn3 | MBGn4 | MBGn5 | MBGn6 | MBGn7 | MBGn8 | MBGn9 | MBGnlO | MBGnll | |

| Di en | 1.23 | 2.777 | 810 | 3.55 0 | |||||||

| Hyen | 1.5 0 | 5.10 | 4.70 | 3.33 | 5.9 0 | 810 | 6.70 | 3.70 | 3.7 0 | 3.80 | 3.60 |

| mt | 7.2 0 | 5.10 | 7.(03 | 3.35 | 4.5? 0 | 11.00 | 6.40 | 7.90 | 7.9 0 | 404 | -0.60 |

| Il | 2.2 0 | 080 | 080 | 0.45 | 0.80 | 1.60 | 0.90 | 104 | 0.9 0 | 060 | 0.70 |

| he | |||||||||||

| Ap | 1.00 | 040 | 040 | 0.3 0 | 040 | 0.5 0 | 0.33 | 6.40 | 0.38 | 06 0 | 0.3 0 |

| VBGH12 | VBGttB | VBGU4 | IVBGl15 | IVBG1I6 | IVBGn17 | VBGni8 | VBG(6I9 | VBG(l20 | VBGn21 | VBGn22 | |

| 68.22 | 63.8 0 | 63.98 | 63.86 | 74.2 0 | 72.42 | 73.38 | 73.10 | 66.71 | 63.48 | 72.13 | |

| ¦no! | 0.45 | 099 | 086 | 0.97 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 084 | 096 | 0.14 |

| 165.4 0 | 12.1 0 | 13.7 0 | 1-5.6 0 | 13.(3 0 | 1510 | 32.3 6 | 361 0 | 34.3 0 | 35.9 0 | 35.1 0 | |

| FeA | 3.98 | 7.99 | 689 | 7.53 | 145 | 192 | 4.18 | 7.36 | 7.42 | 026 | 1.90 |

| FeO | 3.04 | 4.65 | 5.04 | 2.84 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 1.83 | 036 | 4.65 | 5.78 | 1.33 |

| Mno | 0.10 | 014 | 013 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| VgO | 1.42 | 3.06 | 3.02 | 3.29 | 3.34 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 3.32 | 0.22 | 0.46 |

| CaO | 3.08 | 1.18 | 1.88 | 1.75 | 0.79 | 184 | 1.92 | 3.02 | 3.59 | 390 | 3.67 |

| NaO | 4.3 0 | 228 | 268 | 2.50 | 2.22 | 3.56 | 2.86 | 3.28 | 3.5 0 | 3.73 | 3.27 |

| KO | 1.43 | 291 | 280 | 3.12 | 6.3 0 | 3.59 | 3.89 | 3.66 | 2.43 | 2.74 | 4.49 |

| 0.13 | 076 | 018 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 007 | 020 | Q21 | 0.(3! | |

| LO | 0.32 | 1.10 | 085 | 0.73 | 038 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.28 |

| Total | 10287 | 103.06 | 105.01 | 151.72 | 152.92 | 99.86 | 101.38 | 15270 | 103.64 | 102.797 | 10063 |

| A | 5.23 | 5.09 | 5.48 | 5.62 | 852 | 7.15 | 6.75 | 394 | 4.93 | 5.47 | 7.76 |

| Fe* | 7.02 | 12.64 | 11.93 | 10.37 | 1.66 | 2 15 | 6.01 | 4.72 | 1107 | 13.04 | 3.23 |

| LogF/K | 0.44 | 044 | 039 | 0.38 | -0.64 | -0.27 | 0.03 | -0.03 | 0.42 | 0.42 | -0.37 |

| S/A | 4.16 | 3.61 | 4.14 | 4.44 | 5.38 | 4.80 | 5.97 | 5.58 | 4.67 | 3.99 | 4.78 |

| LogS/A | 0.62 | 056 | 062 | 065 | 0.73 | 0168 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 067 | 0.60 | 0.68 |

| R¡Os/TiO¡ | 0.30 | 077 | 021 | 0.12 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.60 |

| VgC/CaO | 0.46 | 255 | 161 | 1.88 | 4.22 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| CIPWNor | |||||||||||

| Q | 28.5 0 | 32.2 0 | 29.5 0 | 30.00 | 30.6 0 | 33.3 0 | 37.3 0 | 35.3 0 | 33.4 0 | 29.6 0 | 31.4 0 |

| Or | 8.40 | 17.1 0 | 16.5 0 | 18.3 0 | 37.00 | 21.10 | 22.9 0 | 215 0 | 14.3 0 | 16.11 | 26.4 0 |

| Ab | 36.07 | 18.3 0 | 22.5 0 | 20.9 0 | 18.6 0 | 29.8 0 | 24.00 | 27.5 0 | 21.00 | 22.9 0 | 27.4 0 |

| An | 14.35 | 1.40 | 810 | 7.90 | 3.40 | 850 | 9.00 | 9.5 0 | 115 0 | 13.00 | 7.72 |

| C | 2.5 0 | 10.00 | 5.3 0 | 4.20 | 2.10 | 220 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 3.3 0 | 3.70 | 2.00 |

| Di wo | |||||||||||

| Di en | |||||||||||

| Hyen | 5.2 0 | 860 | 10.00 | 8.2 0 | 830 | 1.34 | 0.90 | 0.72 | 7.80 | 3.80 | 1.90 |

| mt | 5.80 | 11.6 0 | 10.00 | 65.80 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 4.80 | 3.40 | 9.3 0 | 10.5 0 | 2.70 |

| Il | 0.90 | 1.90 | 160 | 1.80 | 0.2 0 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 1.60 | 180 | 0.3 0 |

| he | 1.70 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ap | 0.29 | 1.70 | 040 | 0.25 | 0.2 0 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.2 0 | 0.4 0 | 0.45 | 0.2 0 |

Table 3. Major element oxide (wt %) compositions and CIPW norm valúes of the garnet biotite schist around Njuakaku, southeast of Ogoja./Tabla 3. Composiciones de óxido de elemento principal (% en peso) y valores normativos CIPW del esquisto de biotitagranate alrededor de Njuakaku, al sureste de Ogoja.

| GBS1 | GBS2 | GBS3 | GBS4 | GBS5 | GBS6 | |

| SiOz | 61.05 | 62.71 | 60.86 | 60.67 | 57.09 | 65.16 |

| TiOz | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 1.14 | 0.80 |

| Al2O3 | 16.60 | 15.10 | 17.50 | 17.80 | 18.10 | 15.10 |

| Fe2O3 | 7.75 | 7.48 | 8.62 | 8.25 | 9.18 | 6.84 |

| FeO | 5.97 | 5.81 | 0.13 | 1.64 | 7.10 | 5.03 |

| MnO | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| MgO | 4.07 | 3.86 | 4.31 | 4.21 | 3.93 | 3.56 |

| CaO | 2.92 | 2.85 | 1.51 | 2.13 | 1.16 | 2.67 |

| NazO | 2.84 | 2.77 | 1.90 | 3.42 | 2.01 | 2.62 |

| KzO | 2.78 | 2.62 | 2.64 | 2.52 | 3.69 | 2.41 |

| p2o5 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| LOI | 0.45 | 0.40 | 1.18 | 0.62 | 1.01 | 0.46 |

| Total | 105.67 | 104.82 | 99.93 | 102.57 | 104.74 | 104.97 |

| A | 5.62 | 5.39 | 4.54 | 5.94 | 5.70 | 5.03 |

| TI ro * | 13.72 | 13.29 | 8.75 | 9.89 | 16.28 | 11.87 |

| LogF/K | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.45 |

| S/A | 3.67 | 4.15 | 3.47 | 3.40 | 3.15 | 4.31 |

| LogS/A | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| P2O5/TÍ O2 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.23 |

| MgO/CaO | 1.39 | 1.35 | 2.85 | 1.97 | 3.38 | 1.33 |

| CIPW Norm | ||||||

| Q | 20.50 | 23.20 | 30.50 | 20.80 | 21.60 | 29.00 |

| Or | 16.30 | 15.40 | 15.50 | 14.80 | 21.70 | 14.20 |

| Ab | 23.80 | 23.20 | 15.90 | 28.70 | 16.80 | 22.00 |

| An | 13.10 | 12.70 | 6.21 | 9.10 | 4.70 | 12.00 |

| C | 4.10 | 3.00 | 9.20 | 6.10 | 9.00 | 3.80 |

| Di wo | ||||||

| Di en | ||||||

| Hy en | 13.40 | 12.90 | 8.60 | 10.40 | 13.60 | 11.30 |

| Ol | ||||||

| mt | 11.20 | 10.80 | 0.60 | 2.90 | 13.20 | 9.90 |

| he | 6.20 | |||||

| ap | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

Figure 5. Bivariate (TiO2 versus SiO2) discrimination diagram./Figura 5. Diagrama de discriminación bivariante (TiO2 versus SiO2).

Figure 6. Plots of gneisses and schists on the log (SiO2/A]2O2) vs. Log (Ffe2O3(t)/K2O) diagram for the discrimination of sedimentary protoliths./Figura 6. Gráficos de gneisesy esquistos en el diagrama log (SiOJAip) vs. Log(Fepfit)/Kp) _para la discriminaáón deeprotiolitos sedimentarios.

Rare-earth elements

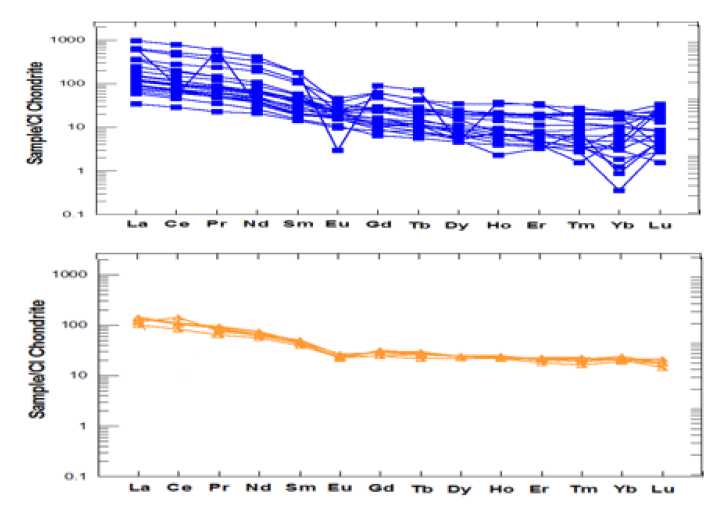

The rare-earth elements compositions (ppm) of the rocks are presented in Table 6 and 7. Generally, the REE pattern for both the gneisses and schists display Light REE enrichment relative to Moderate REE and Heavy REE. The gneisses and the schists show light negative Eu anomaly. Whereas the gneisses show inclined MREE and flat HREE, the schists show flat MREE and HREE (Figure 9). Specifically, the Eu-anomalies, expressed as (Eu/Eu*) ranges from 0.02 to 1.4 in the gneisses and from 0.09 to 1.1 in the schist. The LaN/YbN ratios range from 7 to 93 for the gneisses and 1.9 to 46.4 for the schist.

Figure 7. Ternary Plot of K2O-TiO2-P2O5 showing continental discrimination of gneisses and schists./Figura 7.Gráfico ternario de K2O-TiO2-P2O5 que muestra la discriminación continental de gneis y esquistos.

Degree of alteration of theprotoliths

Molar proportions of chemical index of alteration CIA = 100[Al2O3/(Al2O3+-CaO*+Na2O+K2O)] in molecular proportions where CaO* is CaO in silicates only (Nesbitt and Young, 1982) was calculated. The CIA records the progressive alteration of potassium feldspars and plagioclase to clay minerals (Rahman and Suzuki, 2007). The index provides a means of ascertaining the extent or degree of weathering of the detritus constituting the protoliths. The values of CIA from the rocks range from 57.7-71.7 in the gneisses and 66.6-74.9 in the schists with mean of 68% and standard deviation of ±3.4. These values point to recycling pro-cesses and relatively moderate chemical weathering of the protoliths. The samples show moderate weathering on the CIA versus SiO2 diagram of Nesbitt and Young (1982) and Taylor and McLennan (1985) (Figure 10).

Discussions

From field and petrographic studies, the study area is underlain by the rocks of the Nige-rian Precambrian Basement Complex including (1) migmatitic banded gneiss, representing the Migmatite-Gneiss Complex or the Basement sensu stricto and (2) garnet-biotite schist repre-senting the Schist belt. Minerals that make up the rocks include: quartz, K-feldspar (micro-cline), plagioclase, biotite, muscovite, chlorite, garnet, cordierite, sillimanite, sphene, zircon and opaques.

The assemblage of quartz + biotite + garnet + K-feldspar + oligoclase + cordierite + sphene + opaque in the migmatitic banded gneiss in the northern part of the study area is typical of the high-grade metamorphism, i.e. middle to upper amphibolite facies. According to Bucher and Frey (1994), the index assembla-ge (garnet + biotite + plagioclase) has stability ranges of 550-600 0C and pressures of 3-10 Kb. The presence of K-feldspar in the absence of muscovite is expected at temperatures >700-750 °C if Al2SiO5 (kyanite or sillimanite) was present.

The mineral assemblage of migmati-tic banded gneiss around Oku and Okundi, located in the western part of the study area represent middle to upper amphibolite facies conditions of metamorphism with tempera-tures of 600-700 0C and pressures of 3-10 Kb based on the stability of garnet (almandine) + biotite + cordierite + sillimanite. Howe-ver, Massone and Schreyer (1987) stated that the presence of K-feldspar and plagioclase might be indicative of the fact that the conditions reached the upper amphibolite facies metamorphism, 670-700 °C. According to Ugwuonah and Obiora (2011), the index mi-nerals could have been formed through the following reactions:*

The characteristic mineral assemblage of the garnet-biotite schist in the study area which includes biotite, plagioclase (An39) and garnet suggests high grade regional metamorphism corresponding to middle amphibolite facies. The growth of garnet with inclusions

*(1). 6[KAl2(AlSiO2O10)(OH2)]+2[K(MgFe)3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2] + 15(SiO2)= 8(KAlSi3O8)+3[(MgFe)2Al3(AlSi5) O18] + 8(H2O), Muscovite Biotite Quartz K-feldspar Cordierite water

(2). 2[KAl2(AlSiO3Oio)(OH2)]+2[K(MgFe)3(AlSi3Oio)(OH)2]+(SiO2)= 4(KAlSi3O8)+Fe3Al2Si3Oi2 + 4(Al2SiO5) + 4(H2O), Muscovite Biotite Quartz K-feldspar Almandine Sillimanite Water of muscovite, biotite and quartz and the garnet surrounded by the crystals of biotite and quartz are some of the microstructures indicating prograde metamorphism while the seri-citization of plagioclase crystals and the myrmekitic structures are indicative of retrograde metamorphism. Alterations by sericitization, together with the myrmekitic intergrowths in the gneisses suggest that retrograde metamorphism was superimposed on these high-grade amphibolite facies rocks (Ugwuonah et al, 2017).

Table 4. Trace elements compositions (ppm) of the gneisses around Njuakaku, southeast of Ogoja./Tabla 4. Composiciones de oligoelementos (ppm) de los gneis alrededor de Njuakaku, al sureste de Ogoja.

| MBGn1 | MBGn2 | MBGn3 | MBGn4 | MBGn5 | MBGn6 | MBGn7 | MBGn8 | MBGn9 | MBGn10 | MBGn11 | |

| Sc | 6.9 | 6.1 | 9.8 | 2.9 | 10.2 | 18.5 | 12.4 | 8.6 | 11 | 6.4 | 3.5 |

| V | 36.7 | 45.3 | 79.6 | 27.7 | 72.8 | 123 | 76.8 | 80.3 | 75 | 46.9 | 44 |

| Cr | 14 | 24 | 39 | 13 | 91 | 124 | 43 | 52 | 50 | 38 | 14 |

| Co | 18.5 | 17.5 | 18.9 | 12.2 | 20.8 | 26.9 | 15.8 | 20.5 | 24.5 | 25.2 | 10.9 |

| Ni | 12 | 20 | 22 | 10 | 62 | 64 | 20 | 26 | 30 | 26 | 8 |

| Cu | 18 | 18 | 6 | 14 | 12 | 54 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 14 | 22 |

| Zn | 125 | 60 | 60 | 35 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 60 | 40 | 40 |

| Ga | 21.8 | 21.3 | 19.7 | 13.3 | 17.4 | 22.2 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 17.8 | 22.2 | 20.8 |

| Rb | 238 | 102 | 48.6 | 43.9 | 83 | 91.4 | 69.4 | 79.9 | 51.2 | 32.2 | 35.2 |

| Sr | 334 | 608 | 578 | 469 | 511 | 444 | 450 | 401 | 430 | 692 | 685 |

| Y | 32.4 | 8.6 | 11.1 | 6.28 | 15.5 | 34.5 | 12.2 | 12.3 | 13.6 | 8.12 | 8.08 |

| Zr | 890 | 150 | 118 | 94 | 176 | 214 | 121 | 199 | 113 | 130 | 171 |

| Nb | 40.3 | 6.47 | 3.59 | 7.01 | 4.61 | 16.2 | 4.24 | 3.75 | 4.02 | 3.53 | 1.53 |

| Sn | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Sb | 0.5 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 |

| Cs | 0.84 | 1.46 | 0.41 | 1.12 | 2.05 | 3.52 | 1.89 | 1.79 | 1.66 | 0.9 | 0.63 |

| Ba | 1670 | 430 | 512 | 358 | 635 | 504 | 636 | 818 | 489 | 494 | 346 |

| Hf | 22.2 | 3.4 | 2.81 | 2.33 | 4.14 | 5.32 | 5.2 | 5.73 | 3.25 | 2.88 | 4.72 |

| Ta | 3.07 | 0.6 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 1.22 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.09 |

| W | 216 | 203 | 144 | 122 | 140 | 90.4 | 90.8 | 91.7 | 150 | 220 | 68.4 |

| Tl | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Pb | 27 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 6 |

| Th | 68.4 | 3.12 | 1.79 | 3.52 | 8.08 | 12 | 5.68 | 5.81 | 3.79 | 1.97 | 0.38 |

| U | 2.4 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.54 | 2.93 | 0.63 | 1.19 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| Ga | 21.8 | 21.3 | 19.7 | 13.3 | 17.7 | 22.2 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 16.7 | 22.2 | 20.8 |

| Y+Nb | 72.7 | 15.07 | 14.69 | 13.29 | 20.11 | 50.7 | 16.44 | 16.05 | 17.62 | 11.65 | 9.61 |

Table 4: Continued

| MBGn12 | MBGn13 | MBGn14 | MBGn15 | MBGn16 | MBGn17 | MBGn18 | MBGn19 | MBGn20 | MBGn21 | MBGn22 | |

| Sc | 12.2 | 18.4 | 16.2 | 19.2 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 12.6 | 16.3 | 3.4 |

| V | 49 | 146 | 128 | 151 | 6.9 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 13.4 | 122 | 137 | 9.8 |

| Cr | 30 | 127 | 115 | 120 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 93 | 111 | 1 |

| Co | 18 | 23.9 | 33 | 25.8 | 25.5 | 24.5 | 14.9 | 16.8 | 24.5 | 29.2 | 17.5 |

| Ni | 28 | 98 | 70 | 68 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 58 | 68 | 6 |

| Cu | 94 | 80 | 28 | 44 | 8 | 6 | 18 | 16 | 44 | 24 | 8 |

| Zn | 40 | 120 | 90 | 110 | 25 | 40 | 65 | 70 | 55 | 80 | 30 |

| Ga | 17.2 | 24 | 17.5 | 18.8 | 11.5 | 15.3 | 13.3 | 14.9 | 16.2 | 17.3 | 15.3 |

| Rb | 38.7 | 136 | 95.7 | 120 | 119 | 84.3 | 43 | 39.8 | 79.6 | 82.9 | 98.9 |

| Sr | 681 | 165 | 213 | 200 | 187 | 196 | 174 | 190 | 181 | 199 | 207 |

| Y | 21.6 | 29.5 | 33 | 28.1 | 7.78 | 12.3 | 52.5 | 35.8 | 33.2 | 34.2 | 11 |

| Zr | 275 | 240 | 209 | 197 | 71.5 | 264 | 688 | 514 | 193 | 225 | 144 |

| Nb | 6.11 | 14.6 | 10.1 | 13.9 | 1.99 | 3.49 | 9.64 | 9.44 | 11.2 | 11.7 | 2.44 |

| Sn | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Sb | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Cs | 1.94 | 4.3 | 4.69 | 5.89 | 1.42 | 1.54 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 4.24 | 5.07 | 1.39 |

| Ba | 697 | 849 | 552 | 660 | 1410 | 791 | 2470 | 2200 | 492 | 522 | 1080 |

| Hf | 7.36 | 6.93 | 6.02 | 5.73 | 2.25 | 7.7 | 15.9 | 11.5 | 5.02 | 5.92 | 4.48 |

| Ta | 0.51 | 0.8 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.9 | 0.96 | 0.34 |

| W | 170 | 53.6 | 235 | 82.2 | 530 | 236 | 180 | 186 | 96.1 | 121 | 189 |

| Tl | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Pb | 27 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 44 | 34 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 16 | 41 |

| Th | 14.2 | 18.1 | 8.25 | 7.66 | 10.1 | 55 | 8.46 | 4.59 | 8.63 | 8.1 | 25.4 |

| U | 2.95 | 2.85 | 2.11 | 2.46 | 1.42 | 5.66 | 1 | 0.42 | 2.34 | 2.84 | 3.02 |

| Ga | 17.2 | 24 | 17.8 | 18.8 | 11.5 | 15.3 | 13.3 | 14.9 | 16.2 | 17.3 | 15.3 |

| Y+Nb | 27.71 | 44.1 | 43.1 | 42 | 9.77 | 15.79 | 62.14 | 45.24 | 44.4 | 45.9 | 13.44 |

Myrmekitic intergrowth is commonly associated with the breakdown of feldspars in gneisses and indicative of retrograde metamorphism (Ugwuonah et al., 2017).

As observed in this study, biotite and quartz showed considerable variations in their sizes; also, different grains of plagioclase showed different compositions which were also obvious in their different anorthite compositions. This may be indicative of a metase-dimentary origin for the rocks (Obiora, 2006). The presence of almandine garnet in the mig-matitic banded gneisses and the garnet-biotite schists confirms a pelitic sedimentary origin for the rocks.

On a TiO2 versus SiO2 diagram of Tar-ney (1977), the gneisses and the schists domi-nantly plot in sedimentary field (Figure 6).

The plot of log (Fe2O3(t)/K2O) vs log (SiO2/Al2O3) after Herron (1988) shows that the protoliths of the gneisses are predominantly Fe-shale, Fe-sand and greywacke and ar-kose while those of the schists are shales and greywackes.

Table 5. Trace elements compositions (ppm) of the garnet biotite schist around Njuakaku, southeast of Ogoja./Tabla 5. Composiciones de oligoelementos (ppm) del esquisto de biotitagranate alrededor de Njuakaku, al sureste de Ogoja.

| GBS1 | GBS2 | GBS3 | GBS4 | GBS5 | GBS6 | |

| Sc | 21.5 | 19.4 | 22.7 | 22.9 | 26.4 | 18.8 |

| V | 168 | 149 | 179 | 173 | 173 | 137 |

| Cr | 126 | 111 | 120 | 120 | 161 | 102 |

| Co | 30.2 | 26.2 | 36.3 | 29.4 | 27.9 | 29 |

| Ni | 80 | 76 | 90 | 90 | 88 | 68 |

| Cu | 12 | 8 | 114 | 58 | 46 | 10 |

| Zn | 120 | 105 | 130 | 115 | 130 | 95 |

| Ga | 20.8 | 18.1 | 21.3 | 21.1 | 24.5 | 16.4 |

| Rb | 92.9 | 85.6 | 88.1 | 82.2 | 137 | 80.8 |

| Sr | 224 | 217 | 156 | 168 | 235 | 211 |

| Y | 36.2 | 36.2 | 37.1 | 38.5 | 37.2 | 31.3 |

| Zr | 189 | 176 | 194 | 201 | 230 | 163 |

| Nb | 9.7 | 9.6 | 9.21 | 9.99 | 16.1 | 8.17 |

| Sn | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 2 |

| Sb | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Cs | 5.23 | 5.04 | 4.64 | 4.49 | 6.7 | 4.52 |

| Ba | 548 | 528 | 526 | 468 | 767 | 479 |

| Hf | 4.95 | 4.67 | 5.05 | 5.94 | 6.64 | 4.25 |

| Ta | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.8 | 1.11 | 0.7 |

| W | 161 | 134 | 175 | 126 | 51 | 154 |

| Tl | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Pb | 18 | 17 | 12 | 13 | 18 | 16 |

| Th | 7.07 | 7.45 | 8.12 | 8.73 | 9.23 | 6.16 |

| U | 2.13 | 2.65 | 2.86 | 2.7 | 3.29 | 1.93 |

| Ga | 20.8 | 18.1 | 21.3 | 21.1 | 24.5 | 16.4 |

| Y+Nb | 45.9 | 45.8 | 46.31 | 48.49 | 53.3 | 39.47 |

The TiO2/ Al2O3 ratio of the migmatitic rocks points towards a mixed nature of the parent rocks which are predominantly made up of greywacke, shales with surbodinate basic to intermedíate volcanic components as deduced from the geochemical character of the rocks.

Truswell and Cope (1963), McCurry (1976), Ajibade et al. (1979), Holt (1982), Obiora (2006) and Danbatta (2008) had established sedimentary protoliths for the metamorphic rocks in the Nigerian Precambrian Basement Complex. However, there are contrasting views concerning the evolution of the gneisses. Some authors believe that the gneisses are of igneous protolith while others noted that some gneisses evolved from partial melting of pre-existing metasediments (McCurry, 1971; Obiora, 2012). The overall geochemical data of the schists and gneisses suggests that their sedimentary progenitors were derived from a cratonic source (Taylor and McLennan, 1985; Das et al., 2008).

Conclusión

The assemblage of the migmatitic ban-ded gneiss around the northern, western and central parts of the study area is typical of middle to upper amphibolite facies with stability ranges of 550-700 °C and pressures of 3-10 Kb. The characteristic mineral assemblage of the garnet-biotite schist in the eastern part of the study area suggests high grade regional metamorphism corresponding to the middle amphibolite facies. Although several theories have emerged as to the origin of myrmekite in metamorphic rocks, the alterations by sericiti-zation together with the myrmekitic intergrow-ths in the gneisses could mean that retrograde metamorphism was superimposed on these hi-gh-grade amphibolite facies rocks. The gneisses were confirmed to be derived from shale, greywackes and arkosic sands while the schists were derived from shales and greywackes. The CIA valúes point to recycling processes and relatively moderate chemical weathering of the protoliths. The overall geochemical data of the schists and gneisses suggests that their sedimentary progenitors were derived from a cratonic source. This result is consistent with other parts of the Nigerian Precambrian Base-ment complex.

Figure 8. Chondrite-normalized Spidergram for MBGn and GBS./Figura 8. Spidergram normalizado con condrilas para MBGny GBS.

Figure 9. Chondrite-normalized REE diagrams for MBGn and GBS./Figura 9. Diagramas REE normalizados con condrila para MBGny GBS.

Figure 10. CIA (Chemical Index of Alteration) versus SiO2./Figura 10. CIA (índice químico de alteración) versus SiO2.

Table 6. Rare-earth elements compositions (ppm) of the gneisses around Njuakaku, southeast of Ogoja./Tabla 6. Composiciones de elementos de tierras raras (ppm) de los gneis alrededor de Njuakaku, al sureste de Ogoja.

| MBGn1 | MBGn2 | MBGn3 | MBGn4 | MBGn5 | MBGn6 | MBGn7 | MBGn8 | MBGn9 | MBGn10 | MBGn11 | |

| La | 231 | 21.9 | 15.6 | 14.1 | 36.3 | 34.5 | 18.5 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 17.5 | 8.17 |

| Ce | 479 | 45.5 | 32.2 | 28.1 | 73.6 | 71.2 | 41.2 | 46.1 | 44.1 | 37 | 17.4 |

| Pr | 55.9 | 5.79 | 55.2 | 3.36 | 8.55 | 8.54 | 4.6 | 5.07 | 5.91 | 4.81 | 2.19 |

| Nd | 191 | 21.4 | 15.8 | 12.1 | 31.2 | 31.8 | 17.3 | 18.8 | 23.9 | 21.4 | 9.77 |

| Sm | 27.70 | 4.6 | 2.95 | 2.36 | 5.36 | 6.53 | 3.23 | 3.23 | 4.13 | 3.72 | 2.2 |

| Eu | 2.08 | 1.04 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.19 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.98 | 1.34 | 0.56 |

| Gd | 12.60 | 3.32 | 2.44 | 1.34 | 3.28 | 5.6 | 2.52 | 2.16 | 2.9 | 2.24 | 1.73 |

| Tb | 1.63 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Dy | 6.34 | 1.87 | 2.2 | 1.16 | 2.82 | 5.93 | 0 | 2.2 | 2.28 | 1.31 | 1.52 |

| Ho | 1.11 | 0.3 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.54 | 1.23 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.39 |

| Er | 2.88 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 0.59 | 1.34 | 3.18 | 0.54 | 1.18 | 1.25 | 0.67 | 0.81 |

| Tm | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Yb | 1.78 | 0.52 | 0.21 | 1.37 | 1.76 | 3.65 | 0.15 | 1.06 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.32 |

| Lu | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| IREE | 1013.56 | 107.56 | 129.76 | 65.7 | 166.87 | 175.42 | 89.92 | 103.3 | 109.74 | 91.74 | 45.52 |

| ILREE | 984.6 | 99.19 | 121.75 | 60.02 | 155.01 | 152.57 | 84.83 | 94.7 | 100.54 | 84.43 | 39.73 |

| IHREE | 26.88 | 7.33 | 7.04 | 5.05 | 10.67 | 21.56 | 4.09 | 7.7 | 8.22 | 5.97 | 5.23 |

| ILREE/HREE | 36.62 | 13.53 | 17.29 | 11.88 | 14.52 | 7.07 | 20.74 | 12.29 | 12.23 | 14.14 | 7.59 |

| LaN/YbN | 93.08 | 30.20 | 53.28 | 7.38 | 14.79 | 6.77 | 88.46 | 14.54 | 31.03 | 14.59 | 18.31 |

| CeN/YbN | 74.75 | 24.30 | 42.59 | 5.69 | 11.61 | 5.41 | 76.29 | 12.08 | 23.55 | 11.95 | 15.10 |

| LaN/SmN | 5.38 | 3.07 | 3.41 | 3.85 | 4.37 | 3.41 | 3.69 | 4.29 | 3.51 | 3.03 | 2.39 |

| LaN/LuN | 112.53 | 58.67 | 13.93 | 21.58 | 19.45 | 6.84 | 15.25 | 14.40 | 12.69 | 15.62 | 12.50 |

| Eu/Eu* | 0.34 | 0.81 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 0.86 | 1.41 | 0.87 |

| MBGn12 | MBGn13 | MBGn14 | MBGn15 | MBGn16 | MBGn17 | MBGn18 | MBGn19 | MBGn20 | MBGn21 | MBGn22 | |

| La | 57.8 | 46.7 | 29.6 | 26.5 | 21.2 | 144 | 152 | 86.4 | 28.1 | 150 | 82.8 |

| Ce | 114 | 93.2 | 61.6 | 54.4 | 43 | 277 | 317 | 172 | 58.5 | 58.4 | 123 |

| Pr | 14 | 11.5 | 7.79 | 6.66 | 5.11 | 32.6 | 40.2 | 22.7 | 7.38 | 7.67 | 14 |

| Nd | 50.6 | 42.2 | 33.3 | 28 | 17.3 | 112 | 157 | 91 | 28.5 | 30.3 | 50.4 |

| Sm | 8.81 | 8.44 | 6.88 | 6.2 | 3.03 | 18.1 | 27.5 | 16.1 | 5.93 | 7.1 | 8.79 |

| Eu | 1.99 | 1.23 | 1.62 | 1.15 | 0.92 | 1.32 | 0.17 | 2.64 | 1.47 | 1.36 | 1.16 |

| Gd | 5.4 | 6.12 | 5.84 | 4.75 | 1.84 | 9.97 | 18.6 | 12.8 | 5.08 | 5.83 | 4.79 |

| Tb | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 0.24 | 1.09 | 2.64 | 1.6 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 0.58 |

| Dy | 4.25 | 5.2 | 5.91 | 4.8 | 1.64 | 3.84 | 1.16 | 8.76 | 5.05 | 5.83 | 2.4 |

| Ho | 0.81 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 2.12 | 1.88 | 1.14 | 1.19 | 0.4 |

| Er | 1.88 | 3.27 | 3.36 | 2.7 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 5.27 | 5.71 | 3.03 | 3.23 | 1.04 |

| Tm | 0.28 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.13 |

| Yb | 1.77 | 3.27 | 3.31 | 3.07 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 3.71 | 2.6 | 2.85 | 3.49 | 0.8 |

| Lu | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| IREE | 262.97 | 224.24 | 162.33 | 140.53 | 95.38 | 602.45 | 728.4 | 425.01 | 148.92 | 276.82 | 291.08 |

| ILREE | 245.21 | 202.04 | 139.17 | 121.76 | 89.64 | 583.7 | 693.7 | 388.2 | 128.41 | 253.47 | 278.99 |

| IHREE | 15.77 | 20.97 | 21.54 | 17.62 | 4.82 | 17.43 | 34.53 | 34.17 | 19.04 | 21.99 | 10.93 |

| ILREE/HREE | 15.54 | 9.63 | 6.46 | 6.91 | 18.59 | 33.48 | 20.08 | 11.36 | 6.74 | 11.52 | 25.52 |

| LAN/YbN | 23.42 | 10.24 | 6.41 | 6.19 | 253.44 | 169.32 | 29.38 | 23.83 | 7.07 | 30.82 | 74.24 |

| CeN/YbN | 17.89 | 7.91 | 5.16 | 4.92 | 199.07 | 126.13 | 23.73 | 18.37 | 5.70 | 4.64 | 42.70 |

| LaN/SmN | 4.23 | 3.57 | 2.77 | 2.75 | 4.51 | 5.13 | 3.56 | 3.46 | 3.05 | 13.63 | 6.08 |

| Lan/Lun | 11.06 | 7.94 | 7.20 | 31.55 | 28.40 | 24.11 | 47.91 | 22.58 | 6.40 | 18.69 | 11.23 |

| Eu/Eu* | 0.88 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 1.19 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.54 |

Table 7. Rare-earth elements compositions (ppm) of the schist from the Bamenda massif./Tabla 7. Composiciones de tierras raras (ppm) del esquisto del macizo de Bamenda.

| GBS1 | GBS2 | GBS3 | GBS4 | GBS5 | GBS6 | |

| La | 28.7 | 27.8 | 32 | 33.8 | 33.6 | 24.1 |

| Ce | 7.4 | 86.8 | 64.8 | 66.8 | 66.4 | 50.5 |

| Pr | 7.77 | 7.31 | 8.31 | 9.05 | 8.77 | 6.12 |

| Nd | 30.5 | 29.5 | 31.1 | 35.2 | 34.1 | 26.4 |

| Sm | 6.65 | 6.6 | 7.85 | 7.12 | 7.09 | 5.96 |

| Eu | 1.36 | 1.37 | 1.48 | 1.27 | 1.55 | 1.33 |

| Gd | 5.05 | 6.09 | 6.12 | 6.48 | 5.93 | 5.01 |

| Tb | 1 | 1.1 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.81 |

| Dy | 6.04 | 6.04 | 6.33 | 6.08 | 6.1 | 5.64 |

| Ho | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.4 | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.22 |

| Er | 3.74 | 3.4 | 3.46 | 3.62 | 3.67 | 2.96 |

| Tm | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.42 |

| Yb | 3.39 | 3.56 | 3.48 | 3.71 | 4.09 | 3.23 |

| Lu | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| ^REE | 103.98 | 181.79 | 168.24 | 176.64 | 174.6 | 134.15 |

| ZLREE | 81.02 | 158.01 | 144.06 | 151.97 | 149.96 | 113.08 |

| ZHREE | 21.6 | 22.41 | 22.7 | 23.4 | 23.09 | 19.74 |

| ^LREE/HREE | 3.75 | 7.05 | 6.34 | 6.49 | 6.49 | 5.72 |

| LAN/YbN | 6.07 | 5.60 | 46.39 | 6.53 | 5.89 | 5.35 |

| CeN/YbN | 0.60 | 6.77 | 33.92 | 5.00 | 4.50 | 4.34 |

| LaN/SmN | 2.78 | 2.71 | 3.81 | 3.06 | 3.05 | 2.61 |

| LaN/LuN | 5.69 | 6.47 | 6.26 | 6.70 | 8.00 | 5.73 |

| Eu/Eu* | 0.71 | 0.66 | 1.18 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

Key Abbreviations

A= Na20+k20 (alkali); Fe*=Total iron; F/K=Fe2O3/ k20; S/A= SiO2/ Na20+k20 (alkali); Q= Quartz; Or= Ortho-clase; Ab= Albite; An= Anorthite; C= Corundum; Di= Diopside; Hy=Hypersthene; En= Enstatite; Ol= Olivine; mt= magnetite; He=Hematite; Il= Ilmenite; Ap= Apatite; CIPW= Cross, Iddings, Pearson and Washington

Acknowledgements

The assistance of the Association of Applied Geochemists (AAG) in carrying out the whole rock geochemical analyses (In-Kind Analytical support-student initiative program) is greatly acknowledged. The author is grate-ful to Theophilus Clavell Davies for securing the TETFund ((TETFUND/DESS/UNI/

NSUKKA/2017/RP/VOL.I)) which was used for the field work and petrographic studies and also to Smart Chika Obiora for proof reading the thesis which the work was extracted from.

References

Ajibade, A.C., Fitches, WR. and Wright, J.B. 1979. The Zun-geru Milonites, Nigeria: recognition of Major tectonic unit. Revue de Geologie Geographie Physique, 21: 359-363. Annor, A.E. 1998. Structural and chronological relations-hip between the low-grade Igarra schist and its adjoining Okene migmatite-gneiss terrain in the Precambrian exposure of southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Mining Geology, 34 (2): 187-196. of Renuka Lake and wetland sediments, Lesser Himalaya (India): implications for source-area weathering, provenance and tectonic setting. En-vironmental Geology, 54: 137-163. [ Links ]

Danbatta, U.A. 2008. Precambrian crustal development in the northwestern part of Zuru schist belt, northwestern Nigeria. Journal of Mining and Geology, 44 (1): 45-56. [ Links ]

Goldschmidt, VM. 1954. Geochemistry. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 730 p [ Links ]

Herron, M. M. 1988. Geochemical classification of te-rrigenous sands and shales from core or log data. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 58: 820-829. [ Links ]

Holt, R.W 1982. The Geotectonic evolution of the Anka Belt in the Precambrian Basement Complex of Northwestern Nigeria. Unpublished. Ph.D. [ Links ]

Ibe, C.U and Obiora, S.C. 2019. Geochemical characte-rization of Granitoids in Katchuan Irruan area: further evidence for peraluminous and shosho-nitic compositions and post-collisional setting of granitic rocks in the Precambrian Basement Complex of Nigeria. Acta Geochimica, 38(5): 734-752. [ Links ]

Kinnaird, J.A. 1984. Contrasting styles of Sn-Nb-Ta-Zn mineralization in Nigeria. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 2: 81-90. [ Links ]

Kroner, A., Ekwueme B.N and Pidgeon R.T. 2001. The oldest rocks in West Africa: SHRIMP Zircon age for early Archean migmatitic orthogneiss at Ka-duna, Northern Nigeria. Journal of Geology, 109(3): 399-406. [ Links ]

Liegeois, J.P, Abdelsalam, M.G., Ennih, N. and Ouabadi, A. 2013. Metacraton: Nature, genesis and beha-vior. Gondwana Research, 23: 220-237. [ Links ]

Massone, H.J. and Shreyer, W 1987. Phengite Geoba-rometry based on the limiting assemblage with [ Links ]

K-feldspar, Phlogopite and Quartz. Contribution to Mineralogy and petrology, 96: 212-224. [ Links ]

McCurry, P 1971. Pan-African Orogeny in Northern Nigeria: Geological Society of America Bulletin, 82: 32513263. [ Links ]

McCurry, P. 1976. The geology of the Precambrian to lower Paleozoic rocks of Nigeria. In: Kogbe, C.A. (ed.), Geology of Nigeria. Elizaberthan, Lagos, Nigeria. 15-31. [ Links ]

Nigerian Geological Survey Agency (NGSA), 2011. Geological Map of Nigeria. [ Links ]

Nesbitt, H.W and Young, G.M. 1982. Early Proterozoic climates and plate motions inferred from major element chemistry of lutites. Nature, 299: 715-717. [ Links ]

Obiora, S.C. 2006. Petrology and geotectonic setting of the Basement Complex rocks around Ogoja, Southeastern Nigeria. Ghana Journal of Science, 46: 13-46. [ Links ]

Obiora, S.C. 2012. Chemical characterization and tec-tonic evolution of hornblende-biotite grani-toids from the Precambrian Basement Complex around Ityowanye and Katsina-AIa, Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Mining and Geology, 48(1): 13-29. [ Links ]

Pearce, J.A., Harris, N.B.W, Tindle, A.G. 1984. Trace element discrimination diagram for the tectonic in-terpretation of granitic rocks. Journal of Petrology, 25 (4): 956-983. [ Links ]

Rahman J. and Suzuki S. 2007. Geochemistry of sandsto-ne from the Miocene Surma group, Bengal basin, Bangladesh: Implications for provenance, tectonic setting and weathering. Geochemical Journal, 41(6): 415-428. [ Links ]

Spears, D.A and Kanaris-Sotirious, R. 1976. Titanium in some carboniferous sediment from Great Britain. [ Links ]

Geochimica et Cosmochimica acta, 40: 345-351. [ Links ]

Sun, S.S., and McDonough, WF. 1991. Chemical and isotopic systematic of oceanic basalts: implication for mantle composition and processes. In: Sun-ders, A.D., Norry, M.J. (eds.), Magmatic in Oceanic Basins. Geology Society of London, Special Publication, 42, 313-345. [ Links ]

Tarney, J. 1977. Petrology, mineralogy and geochemistry of the Falkland Plateau basement Rocks, site 330, Initial reports-deep sea drilling project, 36: 893921.

Taylor, S.R., and McLennan, S.M. 1985. Continental Crust: its Composition and Evolution. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 311pp.

Thompson R.N. 1982. British Tertiary volcanic province. Scottish Journal of Geology, 18: 49-67.

Truswell, J.F. and Cope, R.N. 1963. The Geology of parts of Niger and Zaria Provinces, Northern Nigeria: Geological Survey Nigeria Bulletin, 29: 52.

Ugwuonah E.N., and Obiora, S.C. 2011. Geothermometric and geobarometric signatures of metamor-phism in the Precambrian basement complex rocks around Keffi, north-central Nigeria. Ghana Journal of Science, 51: 73-87.

Ugwuonah E.N, Tsunogae, T., and Obiora, S.C. 2017. Metamorphic P-T evolution of garnet stauroli-te-biotite pelitic schist and amphibolites from Keffi, north central Nigeria: Geothermobarometry, mineral equilibrium modeling and P-T path. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 129: 1-16.

Recibido: 11 de Mayo del 2020 Aceptado: 20 de Agosto del 2020