Introduction

Fossil bees first appear in the geological record during the Cretaceous, both as body- and ichnofossils (Genise, 2016, 2020). Within the ichnological record, Elipsoideichnus meyeri Rose-lli, 1987 represents an uncommon and significant ichnotaxon, showing the highest observed complexity and bringing together rare examples of helicoidal invertebrate trace fossils (Verde and Genise, 2014). After the first description, Elipsoideichnus meyeri remained as a single spe-cimen until the contribution by Verde and Genise (2014). In addition to the holotype, eight more specimens assigned to Elipsoideichnus were recovered from localities near Nueva Palmira, Dolores and Mercedes cities, all in southwest Uruguay (Verde and Genise, 2014), and one from a museum collection, expanding its distribution and enriching our knowledge about the ichnotaxon. All these discoveries came from the Asencio Formation (Norte Basin, Uruguay), a lithostratigraphic unit traditionally considered Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) in age (see Veroslavsky et al., 2019 and references therein), but for which an Eocene age has also been su-ggested according to different approaches (see Genise, 2016 and references therein).

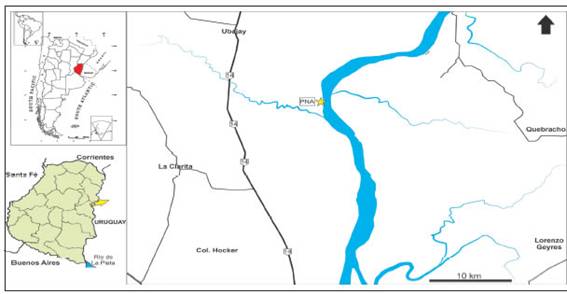

Recently, during fieldworks at Prefectura Nacional Argentina quarry (Parque Nacional El Palmar, Entre Ríos province, Argentina), a new specimen assigned to Elipsoideichnus meyeri, the first outside Uruguay about 150 km north of the northernmost locality bearing the ichnotaxon known to date, was found (Figure 1). The main goals of this work are to present and describe this new record and discuss the lithostratigraphic assignment of the trace-bea-ring unit, its chronostratigraphy and geologi-cal correlations.

Geological and Stratigraphic SettingThe ichnological locality is situated in the Prefectura Nacional Argentina (hereafter PNA) quarry, which is located at the western margin of the Uruguay River, few meters from the coast, 35 km north Colón city, Entre Ríos province, Argentina (Figure 1).

The exposed stratigraphic framework of the Mesopotamia geological province com-prises units ranging between Upper Jurassic/ Lower Cretaceous and Miocene (Aceñolaza, 2007 and references therein). Although Cha-co-Paraná Basin from Argentina and Norte Basin from Uruguay shared an overall common geological history, there are some differences related to different geological processes, besi-des disparities in nomenclature and also lithos-tratigraphic and/or genetic interpretations (e.g. Tófalo, 1986; Chebli et al., 1989; Pazos et al, 1998; Tófalo and Pazos, 2002; Bellosi and Ge-nise, 2004, 2016; Goso and Perea, 2004; Ace-ñolaza, 2007; Morrás et al, 2010; Tófalo et al, 2008; Alonso-Zarza et al, 2011; Genise, 2016; Veroslavsky et al, 2019). Even if a comprehen-sive analysis of the whole regional stratigraphic framework is beyond the scope of this contri-bution, a brief description of more accepted backgrounds is needed in order to evaluate the significance of the new material in disentan-gling pending issues. A summary of regionally distributed units and their chronostratigraphi-cal positions and relationships between Entre Ríos province and Uruguay is provided inFigure 2, which is our interpretation of more accepted schemes suggested by the literature. In Entre Ríos province, the two main strati-graphic discrepancies are related to the Upper Cretaceous-Eocene lapse. Figure 2.A displays the first alternative, which suggests for Entre Ríos that the Upper Cretaceous-Danian lapse is represented by a single unit, the Puerto Yeruá Formation, which would be correlated in Uruguay with three units from bottom to the top: Guichón, Mercedes and Asencio formations, each one lying unconformably. At the right of the scheme, in Figure 2.B, the second alternative is observed, displaying these same units for Entre Ríos province, thus replacing the Puerto Yeruá Formation.

Figure 1: Location map of the Prefectura Naval Argentina quarry (PNA) within the Parque Nacional El Palmar of the Entre Ríos province (Argentina). The yellow star indicates the ichnofossiliferous location. Coordinates are: 31°53'25,85" S - 58°12'15,44" W / Figura 1. Mapa de la ubicación de la cantera de la Prefectura Naval Argentina (PNA) dentro del Parque Nacional El Palmar de la provincia de Entre Ríos (Argentina). La estrella amarilla indica el sitio icnofosilífero. Coordenadas: 31053'25,85" S - 58°12'15,44" O.

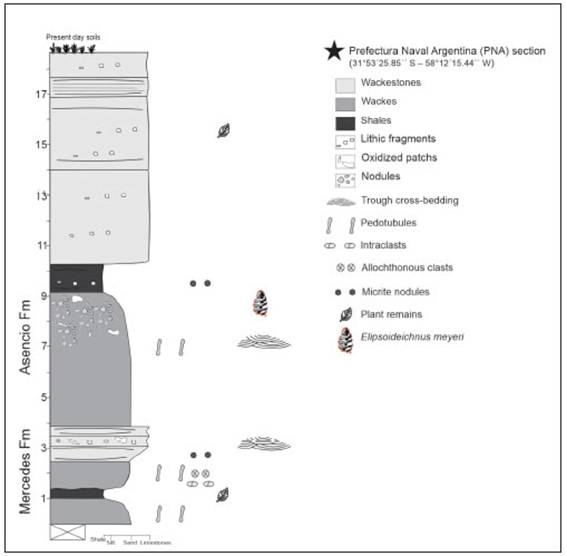

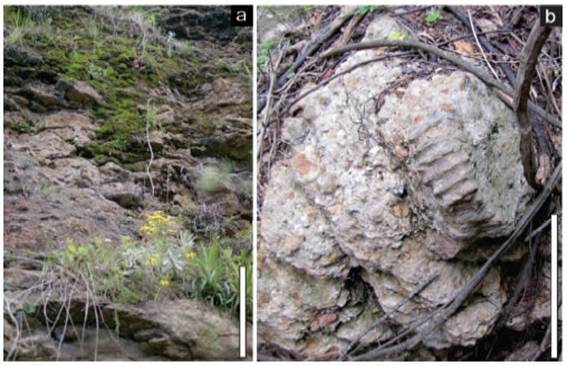

Trace fossil-bearing unitOutcrops of the Elipsoideichnus-bearing unit from Argentina are distributed from the right margin of Uruguay River at Colón city and the Parque Nacional El Palmar, near Concordia city (Aceñolaza, 2007). Trace fossil-bearing stra-ta at PNA section are made up of an averaging 15 m thick succession, with a 18 m maximum (see Tófalo, 1986; Figure 3). This succession is composed of about 10 m of alternated oxidi-zed wackes and shales, with less proportion of wackestones, and wackestones dominance up to the top (Figure 3). Intraclasts, lithic fragments, pedotubules and plant remains are frequent. Se-dimentary structures include slightly parallel la-mination and trough cross-bedding (Figure 3). E. meyeri-hosting facies are made up of reddish nodular edaphized wackes, with slightly trough cross-bedding structures, oxidized patches and pedotubules (Figures 3 and 4). The PNA quarry was traditionally assigned to the Upper Cretaceous Puerto Yeruá Formation (e.g. Tófalo, 1968; Tófalo and Pazos, 2002; Aceñolaza, 2007) or the Cretaceous Pay Ubre Formation (Alonso-Zarza et al., 2011), and could be even assigned to the Eocene Asencio Formation. As commented before, there is not yet a consensus on the stratigraphic framework of this area (see Discussion for further review).

Figure 2: Literature-based Lower Cretaceous - Miocene stratigraphic frameworks of studied area and Norte Basin (Uruguay). A. Left column: stratigraphic framework for Entre Ríos province, based in Tófalo (1986), Aceñolaza (2007), Veroslavsky et a¡ (2019) and references therein. Right column: stratigraphic framework for Norte Basin based in Veroslavsky et a¡ (2019) and references therein. B. Left column: stratigraphic framework for Entre Ríos province, based in Herbst (1980), Chebli eta¡ (1989), Tófalo etd. (2008), Cónsole-Gonella etd (2018) and references therein. Right column: stratigraphic framework for Norte Basin based on Pazos etd. (1998), Bellosi etd. (2004, 2016), Morrás etd. (2010), Tófalo and Pazos (2010), Alonso-Zarza etd. (2011), Tófalo etd. (2011), Genise et al. (2016) and references therein. The star indicates the ichnofossiliferous location. YP means Yapeyú Paleosurface. / Figura 2. Marcos estratigráficos del Cretácico Inferior - Mioceno basados en la literatura del área de estudio y la Cuenca Norte (Uruguay). A. Columna izquierda: marco estratigráfico de la provincia de Entre Ríos, sobre la base de Tófalo (1986), Aceñolaza (2007), Veroslavsky et al. (2019) y referencias alM citadas. Columna derecha: marco estratigráfico para la Cuenca Norte, sobre la base de Veroslavsky et al. (2019) y referencias alícitadas. B. Columna izquierda: marco estratigráfico de la provincia de Entre Ríos, sobre la base de Herbst (1980), Chebli et al. (1989), Tófalo et al. (2008), Cónsole-Gonella et al. (2018) y referencias alM citadas. Columna derecha: marco estratigráfico para la Cuenca Norte basado en Pagos et al. (1998), Bellosi et al. (2004, 2016), Morrás et al. (2010), Tófalo y Pazos (2010), AJonsc-Zarga et al. (2011), Tófalo et al. (2011), Genise et al. (2016) y referencias alM citadas. La estrella indica el sitio icnofosilífem. YP significa Paleosuperficie Yapeyú.

Material and Methods

The specimen is housed in the collection of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales y Antropológicas “Prof. Antonio Serrano”, Paraná city, Entre Ríos province, Argentina, under the co-llection number MAS-Pi-1007.

Descriptions and measurements have been performed by first-hand examination of the specimen, following the conventions sug-gested by Genise (2000, 2016) and Verde and Genise (2014). High-resolution digital photo-grammetry was undertaken to achieve a detai-led representation of trace three-dimensional morphology. To model the studied specimen, the software package Agisoft Metashape Pro (Educational License), which enables creating 3D dense clouds and meshes by means of se-mi-automatic processing of images (Mallison and Wings, 2014), was used. The 60 images se-lected for the photogrammetric process were acquired using a digital camera, with 1.8 focal length and 4.032 x 3.024 pixels of resolution.

Diagnosis

Helicoidal tunnel, circular in cross section, with its main axis vertically oriented. Each whorl bears internally two cells, arising from opposite sides of the whorl and connected to it by means of short, elbowed, lateral tunnels. Openings of lateral tunnels are also helically arranged along the main tunnel. Cells are club-shaped, thick li-ned, and show spiral closures (after Verde and Genise, 2014: 27, modified from Genise, 2000).

Remarks

This ichnogenus is comparable to Cellica-lichnus Genise, 2000, in showing cells connected by tunnels. Nevertheless, Cellicalichnus has straight to slightly sinuous tunnels, whereas Elipsoideicbnus has helicoidal ones (Verde and Genise, 2014). Verde and Genise (2014) made a detailed and extensive revision of the ichno-genus Elipsoideicbnus and so it is not necessary to offer further comments here.

Figure 3: Integrated section of the Prefectura Naval Argentina quarry (PNA) in the Parque Nacional El Palmar of the Entre Ríos province (Argentina). Based on Tófalo (1986) and field data. / Figura 3. Sección integrada de la cantera de la Prefectura Naval Argentina (PNA) en del Parque Nacional El Palmar de la provincia de Entre Ríos (Argentina). Basado en Tófalo (1986)y datos de campo.

Figure 4: Outcrop views. A. Overall outcrop view. Scale bar: 50 cm. B. E. meyeri in situ. Scale bar: 10 cm. / Figura 4. Vistas del afloramiento. A. Vista general del afloramiento. Escala: 50 cm. B. E. meyeri in situ. Escala: 10 cm

Elipsoideicbnus meyeri Roselli, 1987 Type ichnospecies

Elipsoideicbnus meyeri Roselli, 1987 by monoypy.

Provenance

PNA quarry, Parque Nacional El Palmar, Colón, Entre Ríos province, Argentina.

Coordinates: 31°53'25.85" S - 58°12'15.44" W; Figure 1).

Horizon

Asencio Formation (Upper Cretaceous or Eocene) (Bossi, 1966, after Pazos et al., 1998).

Description

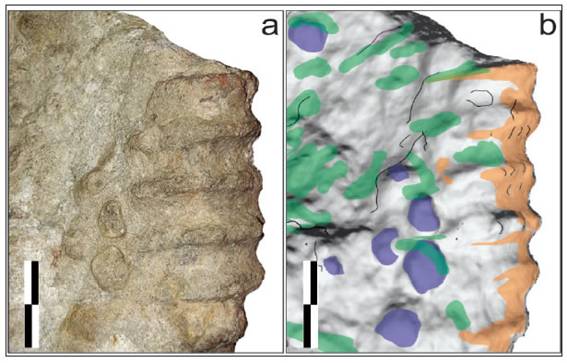

The specimen MAS-Pi-1007 consists of one tridimensional structure (Figure 5), with a dominant cylindrical shape, slightly decreasing in diameter at both endings. It preserves the internal half of a helical tunnel formed of five whorls, each one having a diameter averaging 7.5 mm (Figure 5). The tunnel is 70 mm. long.

The structure is made up of fine grey (10Y 8/2, Munsell, 2009), yellowish (5Y 8/4, Munsell, 2009) and reddish (5R 6/6, Munsell, 2009) sandstone, slightly darker in colour and with finer texture (fine- to medium-grained sand) than host rock (coarse-grained sand to pe-bbles) (Figures 4, 5 and 6). The internal surface of the tunnel shows a smooth polished surface made of fine material (Figure 5), which is typi-cal of previously recorded E. meyeri specimens.

Unfortunately, as occurs in all other re-corded specimens (Verde and Genise, 2014), the external part of the helix lacks in the new material, precluding observation of the presen-ce and possible features of external cells.

Discussion

Taphonomic and paleoenvironmental considerations

Figure 5: Specimen MAS-Pi-1007, Elipsoideichnus meyeri, from PNA quarry. A. Front view showing the helical tunnel and a tunnel entrance (dashed line). B. Lateral view showing the helical tunnel and a tunnel entrance (dashed line). Scale bars: 2 cm. / Figura 5. Espécimen MAS-Pi1007, Elipsoideichnus meyeri, de la cantera de la PNA. A. Vista frontal que muestra el túnel helicoidal y la entrada del túnel (línea discontinua). B. Vista lateral que muestra el túnel helicoidal y la entrada del túnel (línea discontinua). Escala: 2 cm.

As mentioned above, E. meyeri-hosúng fa-cies are made up of reddish nodular edaphized wackes, with slightly trough cross bedding struc-tures, oxidized patches and pedotubules (Figure 4). MAS-Pi-1007 is one of the most complete specimen of E. meyeri recorded until now. It was found in an almost vertical position (Figure 4), supporting the assumption that the construction position locates the helix axis oriented perpendicular to the bedding plane, as in the other specimens (see Genise and Hazeldine, 1998; Verde and Genise, 2014). However, some preservational features suggest some minor degree of rotation within the paleosol substrate after the construction of the nest. It is possible to distinguish vertically oriented, syndepositional, or ear-ly post-depositional fractures, and two different patterns of diagenetic oxidation (Figure 6).

Interpretation

Observed synsedimentary features are probably related to the seasonal alternation and calcretization of floodplain soils (e.g. Tófalo, 1986; Tófalo and Pazos, 2002, 2010; Tófalo et al, 2011; Tófalo and Morrás, 2009; Veroslavsky et al, 2019). This process is sustained by paleoenvironmental data, suggesting a warm and humid to seasonally dry paleoclimate, in agreement with paleobotanical record (Franco et al, 2015). Interestingly, taphonomic process proposed here can be likely related to those des-cribed by Bellosi et al. (2004, 2016) for the facies of Asencio Formation. E. meyeri-hosttng facies at the PNA quarry strongly resembles nodular beds (NB) defined by Bellosi et al. (2004), who further developed these concepts, strengthening original assumptions and redefining the cycle (Asencio cycle) of facies development and ich-noassociations establishment during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (ECO). Each cycle included sedimentation, pedogenesis, ferricreti-zation and dismantling, according to changes in accommodation space and precipitation, which have been recognized in quantities up to three in the Asencio Formation (Bellosi et al, 2016). On this subject, a different approach was ca-rried out by analyzing the contact between the Mercedes and Asencio formations, focusing on weathering processes between both units (Mo-rrás et al., 2010). Regarding the origin of nodular beds, the same authors proposed that nodular strata at the base of the Asencio Formation were originated by weathering that affected greyish sandstones of the Mercedes Formation, instead that by dismantling of duricrust (see in detail in Bellosi et al, 2016; Figure 3).

Lithostratigraphical and chronostratigraphical provenance of E. meyeri and geological correlation

As mentioned before, there is not a single consensus about the regional stratigraphic fra-mework. The assignment to the Puerto Yeruá Formation (e.g. Tófalo, 1986; Aceñolaza, 2007and references therein) needs to be ruled out due to the existence of the regional unconformi-ty between Guichón and Mercedes formations, which has been identified both in Uruguay and Argentina (Tófalo etal, 2008) (see Figure 3 for comparisons). The most reliable alternative sus-tains the stratigraphic scheme divided into these two units (e.g. Herbst, 1980; Chebly et al, 1989). This approach is supported by the Stratigraphic Code of Argentina (see points 18.3, p. 15 and 28.c, p. 26; Comité Argentino de Estratigrafía, 1992).

A first possibility is to assign the E. me-jeri-bearing strata to the Upper Cretaceous Mercedes Formation, or instead, to propose the belonging of these levels to the Eo-cene Asencio Formation. The background suggests both possibilities with about equal strength, beyond some discrepancies in the naming designation of units, already mentioned. Thus, a brief discussion should be appropriated.

Background supporting an Upper Cretaceous age

Several authors suggested a Cretaceous age for the succession exposed at PNA qua-rry, although following different stratigraphi cschemes and names of units. Alonso-Zarza et al. (2011) claimed that nodular and mottled limestones with rhizoliths inferred as pond deposits, assigned to the Upper Cretaceous Pay Ubre Formation, were identified at the same locality, one kilometer to the north of the present record locality (Alonso-Zarza et al., 2011). The Pay Ubre Formation was defined by Herbst (1980) to include limestones outcro-pping in the Corrientes province, Argentina, and also in the Parque Nacional El Palmar area, Entre Ríos province, including specifically the Calera Barquín quarry, a dinosaur remain-bea-ring site (von Huene, 1929; Mannion and Otero, 2012), thus replacing the original assign-ment (i.e. Puerto Yeruá Formation). However, and taking into account the already-mentioned regional unconformity between Guichón and Mercedes formations, it should prevail the co-rrelation of these levels with the Campanian Mercedes Formation (e.g. Herbst, 1980; Chebli et al., 1989; G. Veroslavsky, pers.comm. 2020), or with the Asencio Formation but conferring it an Upper Cretaceous age (Cónsole-Gonella et al, 2018).

Figure 6: Taphonomic analysis of MAS-Pi-1007. A. Best preserved lateral view used to 3D digital modelling. B. Digital model. Orange: high level of weathering/oxidation. Green: moderate to low level of weathering/oxidation. Blue: lithified blocky soil (nodules) aggregates. Black lines: synsedimentary fractures. / Figura 6. Análisis tafonómico de MAS-Pi-1007. A. Vista lateral mejor conservada uú&z®da para modelado digital 3D. B. Modelo digital Naranja: alto nivel de meteorización/axidación. Verde: nivel moderado a bajo de meteonzación/axidación. Azul.: agregados de suelo en bloques tafeados (nodulos). Líneas negras: fracturas sinsedimentarias.

From a paleontological point of view, a left humerus referred to an indeterminate tita-nosaur, recorded in the Calera Barquín quarry (Huene, 1929; Mannion and Otero, 2012), su-pports an Upper Cretaceous age (Aceñolaza, 2007). Moreover, de Valais et al. (2003) des-cribed some other dinosaur remains (i.e. one thoracic ankylosaur osteoderm, a theropod tee-th and one titanosaurid egg fragment) from this unit, in the Ita-i-Corá and Arroyo Mármol loca-lities, around 20 km and 10 km to the northwest respectively from the location reported in this contribution. The record of ankylosaurs in Argentina is restricted to Campanian-Maastrich-tian (see Leanza et al, 2004; Arbour and Currie, 2015). Interestingly, de Valais et al. (2003) also mentioned the record of another isolated dino-saur egg with similar features to the previous finding about 5 km north but lacking a stratigra-phic position. Finally, a Lauraceae fossil wood assigned to Paraperseoxyhn septatum Franco et al, 2015, has been recovered near Puerto Yeruá vi-llage, about 50 km to northeast of PNA quarry, mentioned as Cretaceous age.

Background supporting an Eocene age

A key approach to understanding this chronological assignment can be assessed pro-perly after a brief review of the latest sedi-mentological/pedogenetic/ichnological back-ground of the Asencio Formation (Bossi, 1966) in Uruguay. As mentioned above, the Asencio Formation is the unit hosting all the known E. meyeri specimens from Norte Basin.

Despite several contributions suppor-ting an Upper Cretaceous age for the unit, or even Upper Cretaceous-Paleocene (e.g. Bossi et al, 1975; Genise and Bown, 1996; Veroslavsky and Martínez, 1996; Veroslavsky et al, 1997, 2019 and references therein), there are updated strong background suggesting an Eocene age. Bossi (1966) divided the Asencio Formation into two members, namely Yapeyú and Palacio, being the first lying transitionally over the Mercedes Formation. After Pazos et al. (1998), the Asencio Formation was restricted to the Palacio Member, due to the recognition of the Yapeyú Paleosurface, which is a regional unconformity involving two sedimentary cycles and an intensive edaphization process, under warm humid tropical weather. Genise and Bown (1996), Veroslasky and Martínez (1996) and Pazos et al. (1998) recognized that levels belonging to the “Palacio Section” (sen-su Pazos et al, 1998) should represent paleosols development, instead that fluvial deposition as proposed by Ford (1988). More recently, Bellosi et al (2004) elucidated the process related to the origin of the Asencio Formation facies. These authors established two interfingering facies, namely ferruginized duricrusts and nodular beds, exhibiting transitional to sharps contacts (Bellosi et al, 2004). Necessary climatic condi-tions to allow this process are inferred as pro-duced during the Paleogene Climate Optimum, thus an Eocene age was proposed (Bellosi et al, 2004, 2016), and supported later by Morrás et al. (2010). Despite criticism of this age assignment (see review in Veroslavsky et al, 2019), the bulk of sedimentological/pedogenetic data seems to support an Eocene age.

Geological correlation

As mentioned before, within the Cha-co-Paraná Basin, the Puerto Yeruá Formation has been traditionally assigned to the chronos-tratigraphic range comprising the Cenomanian-Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) lapse (see reviews in Veroslavsky etal., 2019; Tófalo and Pazos, 2002). Tófalo (1986), Tófalo etal. (2011) and Veroslavsky et al. (2019) claimed that the Guichón, Mercedes and Asencio formations, which belong to the Norte Basin in Uruguay, should be correlated with the Puerto Yeruá For-mation of Argentina (see also Apesteguía etal., 2005). Goso and Perea (2004) correlated the Puerto Yeruá Formation (De Alba y Serra, 1959) with Guichón Formation (Lambert, 1939), both units from Argentina. In the same sense, Aceño-laza (2007) synonymised the Upper Cretaceous- Paleogene Puerto Unzué Formation (Gentili and Rimoldi, 1979) from the Norte Basin with the Guichón Formation and Puerto Yeruá For-mation. With less strength in literature, an al-ternative possibility was to include PNA quarry within the also Cretaceous Pay Ubre Formation (e.g. Herbst, 1980; Alonso-Zarza etal, 2011). As already mentioned, the assignment of trace fos-sil-bearing rocks at PNA quarry to the Puerto Yeruá Formation is questioned due to the exis-tence of a regional unconformity between Gui-chón and Mercedes formations, which has been identified both in Uruguay and Argentina (Tófalo et al., 2008, see Figure 2). Thus, following Tófalo et al (2008), it would be more appropriate to correlate these units with those of Norte Basin, keeping the designation and division in be-tween- Guichón and Mercedes formations (seeFigure 2.B). This scheme has been already pro-posed by Herbst (1980) and later by Chebly et al (1989) and agrees with the Stratigraphic Code of Argentina (see points 18.3, p. 15 and 28.c, p. 26; Comité Argentino de Estratigrafía, 1992). Thus, a more possible assignment for PNA quarry would be to confer these strata to the Upper Cretaceous Mercedes Formation (Bos-si, 1966), as a continuity with the Norte Basin of Uruguay, with a final Late Cretaceous-Early Cenozoic deposit of the calcareous Queguay Formation, as also occurs with the end of the Neuquen Group in Patagonia with the Roca Formation (see Apesteguía et al, 2015). Howe-ver, as commented before, a further possibility is the assignment of E. meyeri PNA-hosting levels to the Eocene Asencio Formation (after Pazos et al, 1998), which has been preliminarily pro-posed by Genise and Zelich (2001), and more recently by Cónsole-Gonella et al (2018). Genise and Zelich (2001), based on the paleoichnologi-cal record, proposed a correlation between the Puerto Unzué Formation in Argentina with the Asencio Formation in Uruguay. These authors reported the record of Teisseirei barattinia Roselli, 1939, Uruguay rivasi Roselli, 1939, and Palmirai-chnus castellanosi Roselli, 1939 from two outcrops near the International Bridge General Artigas, which connects the Colón and Paysandú cities, about 65 km to the southeast of Parque Nacional El Palmar, Entre Ríos province (Genise and Zelich, 2001). In this sense, The ichnoassociation of the Asencio Formation seems to be indicative of Eocene age, due to the abundance and nature of associated dung beetle brood ball ich-notaxa, which are related to Eocene large-sized mammals (see review in Genise, 2016). Besides, from a sedimentological and edaphological stan-dpoint, the presence of latentes in the Asencio Formation is only compatible for this latitude with the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (Bellosi et al, 2016).

Interestingly, Souza Carvalho et al. (2009) have described a single specimen of Copri-nisphaera from the Adamantina Formation in Brazil (Bauru Basin), whose age is Upper Cretaceous (Turonian-Santonian). In this sense, Verde (2012) reported the presence of four individuals of Coprinisphaera murguiai in levels of the Upper Cretaceous Mercedes Formation of Uruguay. More recently, Sedorko et al (2019) found structures assigned to Coprinisphaera from the Upper Cretaceous Capacete Formation (Sanfranciscana Basin), also in Brazil. However, until the present date, there are no reliable records older than Eocene age in Argentina and Uruguay (see review in Genise, 2016).

Keeping into account the overall back-ground, it seems clear that the chronostratigra-phy and genesis of the Asencio Formation and its relationship with the counterpart in Argentina are not totally solved, being a topic still in development that exceeds the aims of this con-tribution.

Concluding remarksA new record of E. meyeri reinforces the validity of this rare ichnotaxon, besides opening a new window to further research on insect trace fossils and providing new elements about the chronostratigraphy, geological correlation and sedimentary environments between Chaco Paraná and Norte basins and related areas in South America. Based on the bulk of stratigraphic, sedimentological, and paleopedogenetic data in the literature, the most reliable stratigraphic framework for the studied area should keep the nomenclature adopted in the Norte Basin of Uruguay. This has been stressed by several contributions, being the main argument the presence of a regional unconformity between Guichón and Mercedes formations, which pre-cludes the assignment of this new record of E. meyeri to the Puerto Yeruá Formation. Thus, there are two remaining possibilities: 1- the assignment to the Mercedes Formation, and 2- the assignment to the Asencio Formation. Observed facies similarities of hosting strata between studied trace-bearing outcrops and those of the Asencio Formation in Uruguay, allow the preliminary assignation of PNA strata to this unit. This is reinforced by the record pre-sented here, and due to taphonomic elements supporting the lack of significant horizontal or vertical transport. Regarding the chronostratigraphic assignment of this record, there are no concluding elements to locate it within the Upper Cretaceous or Eocene, being as matter of fact an issue still in flux. There are some elements suggesting that Elipsoideichnus-bearing deposits in Entre Ríos are Upper Cretaceous in age, as some laterally correlatable strata hosting dinosaur remains. At the same time, the ichnological record and some paleopedogenetic/ paleoenvironmental interpretations suggests an Eocene age. Further research is needed to solve this geological/stratigraphic riddle. For the time being the new specimen, which represents the first record of Elipsoideichnus meyeri from Argentina, enriches the scarce record of the ichnota-xon and improves our knowledge of fossil bee nests.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank to authorities of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales y Antropológicas Prof. A. Serrano (Paraná, Entre Ríos pro-vince) for allowing the permits to explore the area under the projects (to S. Apesteguía) “Los tetrápodos del Cretácico de Entre Ríos: Una aproximación faunística e icnológica” of 2012 to 2014 (decreto N° 187 MCyC), extended to 2017 (decreto N° 760 MCyC), and “Estudio geopaleontológico del Cretácico de Entre Ríos” of 2017 (decreto N° 3164 MCyC del 25 de septiembre de 2017), extended to 2020. Authorities of the Parque Nacional El Palmar also allowed the corresponding permits and guards of Prefectura Naval Argentina allowed the access to the coastal cliffs. To A. Ernst for field support and to the community of Colón, Villa Elisa and El Palmar for their kindness and support. Fi-nally, to G. Veroslavsky (Udelar, Uruguay) for his fruitful comments during the course of this work and two anonymous reviewers who im-proved the original version of this work. Field-works were financial and logistic supported by Fundación Azara.

Received : August 28, 2022

Accepted : November 23, 2022