Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Ecología austral

versión On-line ISSN 1667-782X

Ecol. austral v.14 n.1 Córdoba ene./jun. 2004

TRABAJOS ORIGINALES

Does wrong procedence assignment lead to underestimates in groundwater biodiversity?

Hugo R Fernández*

Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina

*Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina.

Present address: Flathead Lake Biological Station, 311 Bio Station Lane, Polson MT 59860-9659, U.S.A. Email: hrfe@csnat.unt.edu.ar

Recibido: 4 de agosto de 2003;

Fin de arbitraje: 16 de septiembre de 2003;

Revisión recibida: 2 de octubre de 2003;

Aceptado: 21 de noviembre de 2003

ABSTRACT. Individuals of certain taxa (e.g., water mites and crustaceans) collected from streams and rivers are often assigned to a surficial benthic origin when the animals clearly display subterranean morphological characteristics. This paper addresses reasons for these errors and proposes ways to minimize such mistakes when sampling.

Keywords: Upwelling; Downwelling; Hydrology; Stygobites; Groundwater habitat; Hyporheic zone.

RESUMEN. ¿Los errores en las asignaciones de procedencia llevan a subestimar la biodiversidad de las aguas subterráneas?: Individuos de ciertos taxa (e.g., hidrácaros y crustáceos) que pueblan aguas subterráneas son coleccionados ocasionalmente en ríos y arroyos y asignados erróneamente al hábitat bentónico. Esto sucede a pesar de su morfología típica de estigobiontes o habitantes del medio subterráneo. Analizo aquí algunas causas de estas inesperadas colecciones. A partir del conocimiento del intercambio de agua subterránea y superficial y de su impacto en la ecología del hábitat acuático, remarco su importancia para el estudio de la biodiversidad acuática.

Palabras clave: Afloramiento; Resumidero; Hidrología; Estigobites; Hábitat subterráneo; Zona hiporreica.

THE PROBLEM OF ASSIGNING HABITATS

In contrast to our relatively detailed understanding of the distribution of taxa in surface waters, we still know little about the extent of biological distributions in groundwater and the specific factors that control these distributions (Boulton et al. 1998). Anyone interested in the ecology of rheophilic invertebrates knows that it is sometimes difficult to attribute habitats of origin to specimens collected using methods like kick-sampling, considering that animals collected in this way may normally inhabit the surficial benthic zone, the hyporheic zone or the deeper phreatic zone of true groundwater (Boulton et al. 1998; Ward et al. 2000). Cook (1980, 1988) remarked on these difficulties for water mites (Acari) in particular, which he later overcame by using subterranean individuals provided for ecologists (Smith & Cook 1994). The use of habitat-specific methods for obtaining samples, such as those for hyporheic water under flood plains or directly in the riverbed can be of value (Schwoerbel 1986; Fernández & Palacios 1989; Di Sabatino et al. 2000). Sometimes we can use indirect morphological evidence (Schwoerbel 1986; Fernández 1995; Ward et al. 2000; Strayer 2001) including eyelessness, lack of pigmentation, elongated limbs and well-developed sensory appendages to determine the habitat of origin. Nevertheless, there are several cases of reputable taxonomists misidentifying hyporheic taxa as surficial because, despite the animalís interstitial characteristics, they were collected from surface substrates (e.g., Viets 1978a, 1978b; Orghidan & Gruia 1983) or drift samples (Viets 1977). It is paradoxical because one of those authors (Orghidan 1959) was the creator of the term "hyporheic". Although these cases might be considered minor mistakes, they can lead to misleading taxonomic and ecological conclusions in later research (Angelier 1962; Petrova 1990; Fernández 1993; Boulton & Stanley 1995; Humphreys 2000; Ward et al. 2000). The present paper is not an exhaustive revision of groundwater ecology but seeks to answer three questions: (1) why have we arrived at this situation which can create problems for the ecologist, the systematist and the biogeographer?; (2) what is the root of this problem?; and (3) how can we resolve it? These questions are important to answer because we are at risk of underestimate groundwater biodiversity at a time when conservation measures are gaining impetus and crucial data are needed on the biology of these aquatic invertebrates.

GROUNDWATER ECOLOGY COMING TO HELP

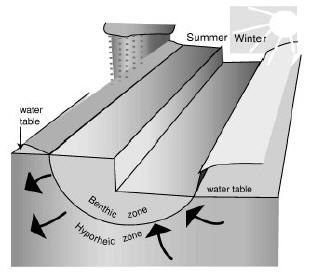

Recent work on the role of surface-subsurface water exchange (Stanford & Ward 1993; Gibert et al. 1994; Boulton et al. 1998) permits us to reinterpret some problematic stygobiotic distributions in flowing water. The occurrence of stygobites and phreatobites (sensu Gibert et al. 1994) in the benthic zone, sometimes very close to the surface (e.g. in Surber, kick or even in drift samples!) can be explained by the complex system of water circulation between the hyporheic zone and the river (Creuzé des Châtelliers et al. 1994). We have frequently been surprised to find stygobiotic forms of water mites and amphipods in unexpected sites (Ginet & David 1963; Fernández et al. 2001). At first, I was convinced that the process was seasonally restricted to those times when the river is fed by subterranean water (Figure 1; Creuzé des Châtelliers et al. 1994). During the wet season (summer), subterranean water receives river waters and the opposite happens during the dry season (winter). Then we could expect to collect stygobites near the surface as they are carried up by upwelling ground water. This process was observed in relation with strong seasonal precipitation in a subtropical region of northwestern Argentina (Fernández & Palacios 1989). In this mountain region, 80% of the annual precipitation occurs in summer (>900 mm). There, most stygobiotic water mites and amphipods were collected at the end of spring, the driest period (Fernández & Palacios 1989). The presence or absence of stygobites in some places may be explained by upwelling (discharge of alluvial aquifer) and downwelling (recharge of alluvial aquifer) zones in the river (Creuzé des Châtelliers 1994). These zones are responding to two different parallel processes (Figure 2) that, as in the case of seasonal movement of ground water, transport the water into or out of the surface river (in a simplistic but graphic sense).

Figure 1. Seasonally gaining (right) or losing (left) South American subtropical stream in relation with the aquifer.

Figura 1. Esquema de un río de América del Sur subtropical que gana agua estacionalmente (derecha) o la pierde (izquierda) en relación con el acuífero.

Figure 2. Simplified diagram showing simultaneous process of upwelling and downwelling along a hypothetical alluvial river.

Figura 2. Diagrama simplificado que muestra el proceso simultáneo de afloramiento (upwelling) y resumidero (downwelling) a lo largo de un río aluvial hipotético.

The vertical and horizontal movements of water mites through different zones (benthic, hyporheic and deeper) in the river system are well known (Schwoerbel 1986). However, at a larger scale (e.g., basin), these migrations are not as significant as the more important physical forces. Thus, we can expect that stygobites will occur predominantly in upwelling and not in downwelling zones (Figure 2). For instance, this last case corresponds to one site in the Medina foothills (Tucuman Province, Argentina), where three bogidiellid amphipod species (Grosso & Fernández 1988) and stygobite water mites (Fernández 2002) were obtained in an upwelling hyporheic zone. Furthermore, we did not obtain any stygobites from the downwelling hyporheic zone upstream of this river. In two other big alluvial valley zones associated with the Piedras and Conchas rivers (Salta Province, Argentina), bogidiellids and stygobite water mites were collected from surficial substrate (Fernández et al. 2001). Coincidentally, Boulton & Stanley (1995) collected stygobites in upwelling zones in a Sonoran Desert stream while surface taxa dominated downwelling zones. This was also well documented in the French Rhône River (see Marmonier et al. 2000).

PLANNING SAMPLING

The seasonal processes of flooding and drought and the spatial locations of upwelling and downwelling can explain the sometimes apparently capricious presence of stygobites in unexpected areas, especially the epigean real. Recognition and detection of the temporal nature of movement of subterranean water and the location of the downwelling and upwelling zones in any river or stream is important for studies of taxa with hyporheic or phreatic affinities. It has even been suggested (Boulton 1993) that surface stream experiments should account for upwelling and downwelling zones when being designed as upwelling water can contribute nutrients and fauna to the stream. The vertical direction of the groundwater movement can be easily measured with minipiezometers (Lee & Cherry 1978). Using these tools we can map out the pattern of upwelling and downwelling zones in the study zone determining the positions of stygobites hotspots. Taking hydrological concepts into consideration, such as water movements (surface-subsurface water exchange), will allow a more rational and efficient planning of biotic surveys, especially if we keep in mind the reservoir of biodiversity contained in groundwater habitats (Palmer et al. 1997; Boulton et al. 1998; Strayer 2001). This consideration will reduce problems in the future by use of more holistic approaches (Schwoerbel 1986; Petrova 1990; Fernández 1993; Humphreys 2000).

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to H. C. Proctor and A. J. Boulton for constructive comments on an earlier draft and to three anonymous reviewers, which provided numerous helpful suggestions. I also thank to P. Feinsinger for his encouragement to publish this opinion and C. von der Pahlen for improving the language. The author is a research scientist for Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Jürgen Schwoerbel.

REFERENCES

ANGELIER, E. 1962. Remarques sur la repartition de la faune dans le milieu interstitiel hyporheique. Zool. Anz. 168:351-356. [ Links ]

BOULTON, AJ. 1993. Stream ecology and surfacehyporheic exchange: implications, techniques and limitations. Aust. J. Mar. Fresh. Res. 44:553-564. [ Links ]

BOULTON, AJ; S FINDLAY; P MARMONIER; EH STANLEY & HM VALETT. 1998. The functional significance of the hyporheic zone in streams and rivers. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29:59-81. [ Links ]

BOULTON, AJ & EH STANLEY. 1995. Hyporheic processes during flooding and drying in a Sonoran Desert stream. Arch. Hydrobiol. 134:27-52. [ Links ]

COOK, DR. 1980. Neotropical water mites. Mem. Amer. Ent. Inst. 31:1-645. [ Links ]

COOK, DR. 1988. Water mites from Chile. Mem. Amer. Ent. Inst. 42:1-356. [ Links ]

CREUZÉ DES CHÂTELLIERS, M; D POINSANT & J-P BRAVARD. 1994. Geomorphology of alluvial groundwater ecosystems. Pp. 157-185 in: J Gibert; D Danielopol & JA Stanford (eds). Groundwater ecology. Academic Press. San Diego. [ Links ]

DI SABATINO, A; R GERECKE & P MARTIN. 2000. The biology and ecology of lotic water mites (Hydrachnidia). Freshwat. Biol. 44:47-62. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, HR. 1993. Acaros intersticiales del noroeste argentino. IV. Análisis filogenético y biogeográfico de Omartacarus Cook (Acari: Omartacaridae): una primera aproximación. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Arg. 52:107-117. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, HR. 1995. Nuevos datos sobre Diamphidaxona yungasa Cook, 1980 (Acari: Hygrobatidae) del noroeste argentino. Neotrópica 41:111-117. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, HR. 2002. Interstitial water mites of Argentina: Omartacarus Cook (Omartacaridae) and Meramecia Cook (Limnesiidae) (Acari: Hydrachnidia). Zootaxa 73:1-6. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, HR & AN PALACIOS. 1989. La fauna intersticial hiporreica de dos ríos de montaña del noroeste de Argentina. Rev. Idrobiol. 28:231-246. [ Links ]

FERNÁNDEZ, HR; F ROMERO; M PERALTA & L GROSSO. 2001. La diversidad del zoobentos en ríos de montaña del noroeste de Argentina: comparación entre seis ríos. Ecología Austral 11:9-16. [ Links ]

GIBERT, J; JA STANFORD; M-J DOLE-OLIVIER & JV WARD. 1994. Basic attributes of groundwater ecosystems and prospects for research. Pp. 7-40 in: J Gibert; D Danielopol & JA Stanford (eds). Groundwater ecology. Academic Press. San Diego. [ Links ]

GINET, R & J DAVID. 1963. Présence de Niphargus (Amphipode Gammaridae) dans certaines eaux épigées des forêt de la Dombes (département de l´Ain, France). Vie Milieu 14:299-310. [ Links ]

GROSSO, LE & HR FERNÁNDEZ. 1988. Un caso de simpatría en tres especies del género Bogidiella (Crustacea, Amphipoda) en el Noroeste argentino, con la descripción de dos nuevas especies. Stygologia 4:64-79. [ Links ]

HUMPHREYS, WF. 2000. Relict fauna and their derivation. Pp. 417-432 in: H Wilkens; DC Culver & WF Humphreys (eds). Subterranean ecosystems. Elsevier. Amsterdam. [ Links ]

LEE, DR & J CHERRY. 1978. A field exercise on groundwater flow using seepage meters and mini-piezometers. J. Geol. Educ. 27:6-10. [ Links ]

MARMONIER, P; M CREUZÉ DES CHÂTELLIERS; MJ DOLE-OLIVIER; S PLÉNET & J GIBERT. 2000. Rhône groundwater systems. Pp. 513-531 in: H Wilkens; DC Culver & WF Humphreys (eds). Subterranean ecosystems. Elsevier. Amsterdam. [ Links ]

ORGHIDAN, T. 1959. Ein neuer Lebensraum des unterirdischen Wassers: der Hyporheische Biotop. Arch. Hydrobiol. 55:392-414. [ Links ]

ORGHIDAN, T & M GRUIA. 1983. Description de deux especes nouvelles d´ Hydracariens de Cuba. Travails Inst. Speleologie "Emile Racovitza" 22:3-8. [ Links ]

PALMER, MA; AP COVICH; BJ FINLAY; J GIBERT; KD HYDE ET AL. 1997. Biodiversity and ecosystem processes in freshwater sediments. Ambio 26:571- 577. [ Links ]

PETROVA, A 1990. Origine et évolution des hydracariens souterrains. Stygologia 5:249-251. [ Links ]

SCHWOERBEL, J. 1986. Acari: Hydrachnellae. Pp. 652- 696 in: L Botosaneanu (ed.). Stygofauna mundi. E. J. Brill. Leiden. [ Links ]

SMITH, IM & DR COOK. 1994. North American species of Neomamersinae Lundblad (Acari: Hydrachnida: Limnesiidae). Can. Entomol. 126:1131-1184. [ Links ]

STANFORD, JA & JV WARD. 1993. An ecosystem perspective of alluvial rivers: connectivity and the hyporheic corridor. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 12:48-60. [ Links ]

STRAYER, DL. 2001. Ecology and distribution of hyporheic microannelids (Oligochaeta, Aphanoneura and Polychaeta) from the eastern United States. Arch. Hydrobiol. 151:493-510. [ Links ]

VIETS, KO. 1977. Rheophilen Wassermilben (Acari, Hydrachnellae) aus Guatemala. Int. J. Acarol. 3:89-98. [ Links ]

VIETS, KO. 1978a. Neue und seltene Wassermilben (Hydrachnellae, Acari) aus Guatemala - Teil III. Acarologia 19:272-297. [ Links ]

VIETS, KO. 1978b. New water mites (Hydrachnellae: Acari) from Australia. Aust. J. Mar. Fresh. Res. 29:77-92. [ Links ]

WARD, JV; F MALARD; JA STANFORD & T GONSER. 2000. Interstitial aquatic fauna of shallow unconsolidated sediments, particularly hyporheic biotopes. Pp. 41-58 in: H Wilkens; DC Culver & WF Humphreys (eds). Subterranean ecosystems. Elsevier. Amsterdam. [ Links ]