Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista veterinaria

versão On-line ISSN 1669-6840

Rev. vet. vol.29 no.2 Corrientes dez. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.30972/vet.2923283

REVISIONES BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

Distribution and pathology caused by Bothriocephalus acheilognathi Yamaguti, 1934 (Cestoda: Bothriocephalidae): a review

Ahmad, F.1; Fazili, K.M.2; Sofi, O.M.3; Sheikh, B.A.1; Sofi, T.A.1

1Department of Zoology, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, India. 2Department of Biotechnology, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, India. 3G.B.Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Pantnagar, India. E-mail: stanveer96@gmail.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.30972/vet.2923283

Abstract

The asian tapeworm or asian fish tapeworm, Bothriocephalus acheilognathi, is native to East Asia and in the past few decades has been spread widely throughout the world via human activities to all continents. Examples of these activities include the movement of cyprinid fish for aquaculture, the pet fish trade, aquatic weed control, mosquito control and more recently due to movement of bait fish. In addition, birds which eat infected fish may transport the cestode’s eggs and spread them through defecation. B. acheilognathi has been reported in an estimated 200 species of freshwater fish, and this wide host range has assisted its establishment, but it is primarily reported from cultured and wild carps. It is a problem for aquaculture and is suspected for adversely affecting endangered wild species. It is listed as a Pathogen of Regional Importance (PRI) by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (2015). The main vector of its spread appears to be the introduction of its native host, the Asian grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella, for aquacultural purposes or for use in the control of aquatic vegetation. At present, it is the common carp, koi carp, mosquito fish, and probably many other fish serve as the main vehicle of expansion of this parasite. The Asian tapeworm is pathogenic to fresh-water fishes, especially young carp fry and may cause great economic loss in hatcheries and fish farms. It has the ability to colonize new regions and adapt to a wide spectrum of fish hosts. It represents one of the most impressive and deplorable examples of a parasite widely disseminated by man assisted movements of fish. The rate of dissemination and success of colonization has been aided by the cosmopolitan distribution of

both intermediate and definitive hosts.

Key words: asian tapeworm Bothriocephalus acheilognathi, pathogenicity, cyprinid fish, dissemination, economic losses.

Resumen

La tenia asiática o tenia asiática de pez, Bothriocephalus acheilognathi, es oriunda de Asia Oriental y en las últimas décadas se ha extendido ampliamente a lo largo del mundo por diversas actividades humanas desarrolladas en todos los continentes. Ejemplos de tales actividades son los traslados de peces para satisfacer demandas de la piscicultura, el comercio de los ejemplares, la disputa por áreas acuáticas, el control de los mosquitos y más recientemente la pesca de peces. Además, las aves que se alimentan de peces infectados, pueden transportar huevos del cestode y diseminarlos a través de la defecación. Estimativamente, B. acheilognathi se ha reportado en unas 200 especies de peces de agua dulce, y este amplio rango de hospedadores colaboró en su establecimiento, aunque el parásito es principalmente reportado en las carpas salvajes y cultivadas. Ello constituye un problema para la acuacultura y se sospecha que afecta adversamente y pone en peligro a las especies silvestres. Es considerado como un patógeno de importancia regional (PRI) por el Servicio de Peces y Vida Silvestre de los Estados Unidos (US Fish and Wildlife Service, 2015). El principal vector de su propagación parece ser la introducción de su huésped natural, la carpa asiática Ctenopharyngodon idella, para su uso en acuacultura o para el control de vegetación acuática. En la actualidad, el principal vehículo de expansión de este parásito es la carpa común (koi carp, pez mosquito), aunque probablemente también intervengan otros peces. La tenia asiática es patógena para los peces de agua dulce, especialmentecarpas jóvenes y alevines, pudiendo causar gran pérdida económica en los criaderos y granjas de peces. Tiene habilidad para colonizar nuevas regiones y adaptarse a un amplio espectro de peces hospederos. Ella representa uno de los ejemplos más impresionantes y deplorables de un parásito ampliamente diseminado por el hombre, asistido por movimientos de peces. El grado de diseminación y éxito de la colonización fue favorecido por la distribución cosmopolita de los huéspedes intermediario y definitivo.

Palabras clave: tenia asiática Bothriocephalus acheilognathi, patogenicidad, pez carpa, diseminación, pérdidas económicas.

Recibido: 8 noviembre 2017

Aprobado: 16 marzo 2018

INTRODUCTION

Bothriocephalus acheilognathi (Figure 1) was first described by Yamaguti (1934) from cyprinids in Japan 142. It was subsequently reported from southern China 143 as B. gowkongensis, which was later synonymized with B. acheilognathi. It was known to be native to the Amur River grass carp in the 1950s 21. Beginning in the 1950s, it was detected in western parts of the former Soviet Union, largely because infected carp were moved to and between fish farms. Consequently it became common and widespread in cultured grass carp and common carp 10.

Figure 1. Scolex of B. acheilognathi with ribbon like segmented body.

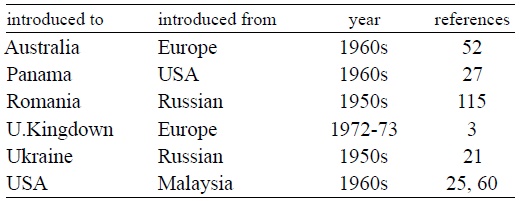

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was known from Ukraine and the Moscow area 21 as well as from Romania 115. In the early 1970s, it spread across eastern and western Europe 125. A steady stream of reports indicated its worldwide presence, for example in Sri Lanka 40 , Malaysia 41, Uzbekistan 104, Hungary 99, Croatia 64, Germany 73, United States of America 46, 47, 48, 58, 59, Czechoslovakia 39, Afghanistan 100, England 3, South Africa 14, 16, 132, 133, Mexico 81, Philippines 6, 134, Hawaii 57, 60, France 32, Italy 93, 123, Iraq 65, Korea 66, 107, Puerto Rico 19, Australia 33, 34, Turkey 8, Canada 24, Panama 27, and most recently Brazil and Honduras 121(Table 1).

Several authors reviewed the spread of B. acheilognathi 10, 28, 60, 107. The year that the parasite was first reported from a country is an unreliable indication of when it was introduced. In countries such as Russia, United States, Mexico and several European countries, there have been multiple shipments of carp and other potentially infected species. For example, grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella, were first introduced into the Czech Republic in 1961 84 but the parasite was not reported from there until the early 1970s.

Table 1. History of introduction of Bothriocephalus acheilognathi.

Similarly, infections in English fish farms were first documented in the early 1980s 3 but were tentatively traced to imports of European common carp, Cyprinus carpio, a decade earlier. These cases could mean that the parasite was present but not detected until later or that it was introduced with a subsequent shipment/introduction, or even by another host. Occasionally, the interval between the parasites actual introduction and its detection can be decades long, such as in Australia and Panama 27, 33, 34, 72.

This is also true for Mexico, where new records continue to accumulate as previously unexplored areas are surveyed 1, 92, 110, 119. The records from Mexico indicate that the parasite may have been introduced by more than one species of host 122.

Distribution. B. acheilognathi is native to eastern Asia but has been spread widely throughout the world (including all continents except Antarctica) by human activities 10. It seems to be widely distributed in China 102 but its status in Japan appears uncertain 25. The records of Bothriocephalus sp from native cyprinids in Africa and India are considered to be B. acheilognathi 74, 112 but this needs to be confirmed by molecular analyses that include tapeworms from native barbs in the interior of Africa and from native cyprinids in streams of the Himalayan foothills 87.

This is particularly important since there is some indication that the Asian fish tapeworm may be a species complex 25, 80, 83. Reports from clariid catfishes in Africa need to be verified because some investigations stated that the species could be confused with another similar tapeworm, Tetracampos ciliotheca 74. Molecular data indicate that isolates from continental North America, Hawaii, and Central America closely match B. acheilognathi isolates from Eurasia 13, 27, 121 (Table 2).

In the United States, the parasite seems to be particularly established in the western and south-western parts of the country 24, 54, 70, 75, 138. In Mexico, it appears to be widely distributed 119, 122. In Australia, it is established in the eastern part of the continent 34. In Europe, it is absent from northern European (Scandinavian) countries; the current status in many central and eastern European countries seems unclear. In South Africa, it is common in carp in certain areas and remains well established.

Species affected. Known world-wide from fish of the families Cyprinidae, Poecilidae, Cichlidae and Centrarchidae. Records of African hosts, all from Southern Africa (Transvaal), include common carp, Barbus kimberleyensis, B. trimaculatus 16, 133 and Oreochromis mossambicus (Van As, personal communication). Records of hosts from the Near East include, Common & Koi carp, Tor (=Barbus) canis, Mirogrex terrae sanctae, Tristramella sp (Cichlidae), Gambussia affinis (Israel); common carp, Barbus sp (Iraq, Khalifa, 1986).

Life cycle and transmission. B. acheilognathi has a simple two host life cycle, involving a planktonic copepod (Copepoda: Cyclopidae) as an intermediate host (Figure 2). In favorable conditions, the life cycle may be completed in about 1 month. Eggs shed by adult parasites into the gut lumen are released into the water with faeces. Depending on water temperature, an embryo (six-hooked oncosphere or hexacanth) is formed within the egg in a few days.

Figure 2. Life cycle and morphology of B. acheilognathi. (a) scolex, (b) total view (segmented body), (c) mature segments (proglottis).

The larva (coracidium) is surrounded by ciliated cells which enable its active movement in the water after hatching from the egg. A number of copepods are suitable intermediate hosts in both experimental and natural conditions. These include species of Acanthocyclops, Cyclops, Macrocyclops, Megacyclops, Mesocyclops, Thermocyclops and Tropocyclops 89, 90 which are considered common in most fresh waters throughout the world 111. Other planktonic crustaceans, such as diaptomids and cladocerans, are not suitable intermediate hosts 96.

After ingestion, the coracidium loses its ciliature and penetrates the gut into the body cavity where is develops from an oncosphere into a plerocercoid (previously also called procercoid, see article for terminology of cestode larvae 23). Larval development is completed in a few weeks depending on the water temperature: within 21-23 days at 28-29°C 78, 79, but 1.5-2 months at 15-22°C 30.

The life cycle is completed when fish ingest infected copepods. Once established within the intestine of a suitable fish, egg production may begin in as little as 20 days 78. It has been shown that transmission of adult parasites can occur from fish to fish via predation by piscivorous fish on infected prey, a phenomenon known as postcyclic transmission 949, 103.

Local spread caused by aquatic birds, such as Anas platyrhynchos and Chlidonias niger, was assumed to take place based on experiments conducted by Prigli 113 and field observations (finding of B. acheilognathi in Ixobrychus minutus) by Borgarenko 15, but this mode of parasite dissemination needs verification. There are also records of the tapeworm in an amphibian (axolotl Ambystoma dumerilii 45) and a snake Thamnophis melanogaster 109 although these records may represent only accidental infection.

Definitive (fish) hosts. The most suitable hosts of B. acheilognathi are cyprinids, especially the common carp (C. carpio) and grass carp (C. idella). However, the parasite has been reported from approximately 200 species of freshwater fishes, representing ten orders and 19 families 122. Nevertheless, maturity of the worm may be reached in only a proportion of these fish species 34. In 1979 it was identified three classes of host 62, in terms of their ability to allow the maturation of parasites: (i) required hosts; (ii) suitable hosts; and (iii) unsuitable hosts.

In required hosts parasites usually obtain full maturity. In ‘suitable hosts’ parasites may gain sexual maturity, but are only found in small numbers, while in ‘unsuitable hosts’ parasites may establish but do not reach maturity. Consequently, although a parasite may infect many fish species, the maintenance of the parasite population may rely on a much narrower range in which reproduction takes place 116, 117. Small fish are more commonly and intensively infected with B. acheilognathi than large hosts 77. In 1999 is detailed a strong negative correlation between size of host and infection intensity of B. acheilognathi 17.

Risk of introduction. B. acheilognathi is mainly spread by the introduction of infected fish hosts. Because it is able to colonize a wide range of fish and copepod hosts, over a broad latitudinal range, accidental introduction of infected fish poses a high risk in any freshwater ecosystem. Movement of water containing tapeworm eggs or infected copepods, especially from water bodies where parasite and copepod densities may be high, also contributes to the risk.

As well as its apparently low host specificity, its simple two-host life cycle using copepods 51, 90 as the intermediate host with fish as the definitive host have underpinned its great success in invading every continent except Antarctica 10, 34. Post-cyclic transmission where small fish infected with larval B. acheilognathi can serve as a source of infection to larger fish can also facilitate wide spread of the parasite 49.

Pathogen characteristics. Mature specimens of B. acheilognathi have a segmented body with an arrowhead-shaped or heart-shaped scolex with bothria (slits) situated dorsoventrally along the scolex terminating with a weak apical disc 143. The worm’s length is variable depending on the host, the ecological setting and age of the host, the age of infection and the number of worms; 3.5-8 cm is typical, although specimens up to 1 m in length have been reported. In addition, the shape of the scolex and bothria are affected by fixation and how they are mounted on glass slides.

The medial position of the genital opening on the segments is of taxonomic importance. Morphological identification should be corroborated with molecular analyses 13. Three species that are easily misidentified as B. acheilognathi are Eubothrium tulipai, E. rectangulum and Bathybothrium rectangulum as they also have a similar scolex with bothria; however, they have lateral rather than medial genital openings 35.

B. acheilognathi attaches to the gut wall by its bothria, which engulf the intestinal folds. The parasite attaches near the anterior portion of the intestine, just posterior to the bile duct. An accumulation of tapeworms in this area leads to digestive tract blockage that distends the intestinal wall leading to perforation. When attached, B. acheilognathi envelopes parts of the intestines and induces an inflammatory response. The inflammation can lead to hemorrhage and necrosis.

Symptoms can also include, weight loss, anemia, and mortality especially in young fishes 107. Infections can be detected by the presence of eggs or body parts in feces, and by the presence of the tapeworm in the gut of the fish (Figure 3). Scolex attachment may also be associated with increased mucus production 126. Tapeworm attachment also provokes a localized inflammatory response, consisting mainly of lymphocytes. In heavy infections, increased numbers of lymphocytes may occur throughout the lamina propria.

Figure 3. Scolex of B. acheilognathi engulfing the intestine of common carp causing compression of the mucosa (arrow) and localized haemorrhage.

Lesions associated with the scolex depend upon the force exerted by the bothria to maintain attachment. The scolex is often pushed firmly against the gut wall causing compression and the formation of localized pits, extending as far as the muscularis (Figures 4 and 5). These attachment sites lead to pronounced thinning of the intestine at these points.

Figure 4. Marked thinning of the intestine, with formation of pits in the intestinal wall caused by the attachment of numerous tapeworms.

Figure 5. Transverse section of common carp showing attenuation of the gut and partial occlusion from tapeworms within.

Scolex attachment can also result in a loss of brush border and an overall reduction in thickness of the terminal web. In advanced cases of infection, scolex attachment can cause localized ulceration. Desquamative catarrhal enteritis and proliferation of connective tissue around the point of scolex attachment have also been recorded 11.

Heckmann provided unique accounts of advanced scolex penetration. Studies on wound fin and round tail chub revealed severe pathology associated with penetration of the gut wall up to the muscularis, resulting in a prominent inflammatory response, extensive haemorrhaging an necrosis. The scolex of some parasites even continued to penetrate the intestine wall into the body cavity, extending as far as the liver and gonads. Thisrepresents an unusual and rarely reported consequence of B. acheilognathi infection 54.

Scolex attachment causes considerable disruption to the intestine, including: (i) destruction of the desmosomal junctions; (ii) loss of the gut microvillous border; (iii) separation and loss of enterocytes; (iv) release of host-cell debris into the gut lumen; and (v) infiltration of leukocytes into the infected area. In hosts less than 4 cm in length, damage through attachment can be extensive and is consistent with disruption of gut enzymes 63.

In many places, the plasmalemma between the microtriches and that of the epithelial cells of the host intestine are lacking, so that the matrix of the tegument is in direct contact with the cytoplasm of the host cells. Lysosomes have been demonstrated surrounding the microtriches embedded in the host cytoplasm 129.

The pathological changes caused by the strobila of B. acheilognathi generally exceed those associated with scolex attachment. The extent and severity of this damage can vary depending on host size, parasite size and intensity of infection 30, 63. In small cyprinid fish, pathological changes are characterized by distension of the intestine, compression of the intestinal folds and pronounced thinning of the gut wall (Figure 5).

In very heavy infections, severe distension may be accompanied by a complete loss of normal gut architecture, with occlusion of the intestine, congestion, compression, pressure necrosis, thinning and atrophy of the mucosa 101 (Figure 5). Separation and degeneration of the epithelium, with regions of complete epithelial loss can occur. Lysis of large areas of the mucosa with necrotic changes has also been observed in heavily infected carp fry 31, 127.

The presence of parasite eggs caught between the parasites and gut wall can lead to epithelial abrasion, exfoliation of host cells and indentation of the mucosa. This damage, combined with an already compressed gut wall, can lead to ulceration. Inflammatory changes may be pronounced during heavy tapeworm burdens, with increased numbers of lymphocytes and eosinophilic granular cells occurring throughout infected regions.

Paradoxically, heavy parasite infections and marked pathological changes have been observed in apparently healthy fish (C. Williams, unpublished data). It was described no signs of mortality, despite serious histopathological changes in common carp fry 101. What is seldom clear in these cases are the metabolic and physiological costs of these infections and the energetic or behavioural demands upon infected fish to maintain condition.

Means of movement and dispersal. B. acheilognathi is mainly spread by the introduction of infected fish hosts such as the common carp (C. carpio) and grass carp (C. idella), often for aquaculture 12, 18, 44, 93. One of the major hosts, C. idella, has been widely used for controlling aquatic weeds and this has resulted in the tapeworm invading places such as North America and Panama 27, 44, 81, 85.

Another suitable host, the mosquitofish Gambusia, is commonly used to control mosquitoes and stocking of this fish probably introduced the tapeworm to California 24, 53, 138. The movement of infected baitfish resulted in the parasite’s successful colonization of the U.S. Southwest 26, 56. The aquarium fish trade is also a potential contributing factor 36, 37, 125.

There have been cases of infected fish escaping from confinement due to flooding 25, or being introduced for ecosystems research 24. Movement of water (and probably vegetation) contaminated with tapeworm eggs or infected copepods can also spread the parasite (R. Cole, personal communication, 2015). Piscivorous birds have also been reported to act as phoretic agents, transporting viable cestode eggs from infected prey and spreading them via defecation 113 (Tables 3 & 4).

Table 3. Vectors of B. acheilognathi.

Control measures. Due to the economic importance of B. acheilognathi, its global distribution and expanding host range, considerable efforts have been made to limit disease impacts. These include: (i) the intervention of stringent legislative controls; (ii) extensive prophylaxis; (iii) veterinary examination of fish stocks; (iv) reduction of intensive stock management; and (v) active therapy 140.

Control of the parasite can be directed at either the copepod intermediate hosts (drainage of the ponds in the spring to eliminate planktonic invertebrates) or the fish stage of the life cycle, although these measures are governed by economic and practical considerations. Fish ponds can be allowed to dry and disinfected with unslaked lime 128.

European fish farmers control bothriocephalosis by drying the ponds annually or treating drained wet ponds with calcium chloride (about 70 kg/ha) or calcium hydroxide (about 2 t/acre) or calcium hypochlorite (HTH) to kill the copepod intermediate host, and treating the fish with anthelmintics. Insecticides employed as ectoparasiticides include Neguvon (Masoten or Dipterex – at 25 ppm, i.e. at 25 g of Masote per ton) or similar compounds (Bromex; Naled), can be used to reduce populations of copepods in ponds 57.

However, these are now banned in many countries as a result of environmental and health concerns. A wide range of chemotherapeutic agents have been employed with varied success including natural products such as: (i) tobacco dust 7 ; (ii) lupin seeds; (iii) conifer needles 68; and (iv) horse radish leaves 69. Also a number of compounds and insecticides have been used 16, 36, 42, 98, 108.

Drugs are usually administered orally. Such preparations are often mixed in oil (corn, soy and fish) and sprayed on to pellets or mixed with feeds. Recent efforts have focused on water-borne chemotherapeutics, which alleviate some of the problems associated with map-potency and dosage. It is important to distinguish the use of treatment to reduce parasite burden and treatment to achieve complete eradication of the infection.

Tapeworms may shed segments during adverse conditions or periods of stress, regenerating when conditions become more favourable. Another important consideration is whether anthelmintics are ovicidal (i.e. kill parasite eggs). This is necessary to avoid the discharge of large numbers of infective eggs to the environment when the worm is evacuated from the fish.

The eggs of B. acheilognathi can be killed rapidly by drying, freezing and ultraviolet rays. Among 11 chemicals tested for ovicidal effect, two chlorine-based compounds were found to be effective: (i) 3.1 ppm of sodium dichloroisocyanurate; and (ii) 9 ppm of bleaching powder 101. However, there are very few chemical treatments currently licensed for use for tape-worm infections. Furthermore, the use of chemicals for the control of parasites in open water bodies can be very difficult, ineffective, harmful, expensive and illegal.

Several chemotherapeutic formulations, when applied in food, effectively relieved fish from infection. Drugs should be mixed in oil (corn, soy, fish) and sprayed on to pellets or mixed with feeds at a rate of one litre per 70 kg dry weight. Di-n-butyl tin oxide: recommended dose, a total of 250 mg per kg of fish, fed over a period of 3 days 94. Dibutyl tin dilurate (Tinostat): a poultry product, recommended to have better efficacy than the above tin formulation 94. Yomesan (niclosamide, Lintex): 50 mg (active ingredient) per kg fish.

Options for application are as follows: 500 g per 500 kg dry pellets fed at 1.5% of body weight, 2–3 times at weekly intervals; 28 g per 40 kg, fed for 3 days. A further option is the incorporation of either of the recommended doses into pellets and distributed over 7 feeding days at 5% of fish body mass 16, 73, 94.

Yomesan, however, is toxic to fish in aquaria and tanks without running water 57, 98. Droncit (Praziquantel): 5 mg/kg of fish, by direct application or incorporated into pellets. Eradication of infection will be more complete if combined with a control of copepods in the pond water. Recommended for use are insecticides employed as ectoparasiticides; Neguvon (Masoten, or Dipterex) or similar compounds (Bromex) 60.

Conclusions and suggestions for future studies. The Asian tapeworm is pathogenic to fresh-water fishes, especially young carp fry, and may cause great economic loss in hatcheries and fish farms. It has the ability to colonize new regions, and adapt to a wide spectrum of fish hosts. It represents one of the most impressive and deplorable examples of a parasite widely disseminated by man assisted movements of fish. The rate of dissemination and success of colonization has been aided by the cosmopolitan distribution of both intermediate and definitive hosts.

However, the spread of B. acheilognathi to many parts of the world has also been the result of inadequate legislative controls, poor preventative measures and lack of appropriate health-checking procedures prior to fish introductions 54, 124. Recent data indicate that the impact of the tapeworm in Europe may have decreased during the last decade. However, surveillance should be maintained to prevent its further expansion to new areas.

Efforts are underway to identify the resistance of different strains of common carp used in European aquaculture. Authors proposed the development of a vaccine against B. acheilognathi, although practical and economic constraints continue to limit this approach 63. Exported fish, especially cyprinids and ornamental species (like guppies), should be inspected by veterinarians before their translocation to prevent further dissemination of the tapeworm into new regions. Control measures are generally effective, including treatment of infected fish, but the use of some anthelmintics are no longer allowed because of their negative effect on human health or the environment.

Future work must therefore seek to accommodate novel and effective treatments to minimize economic loss. Many aspects of the biology, ecology and pathology of B. acheilognathi are well understood and comprehensively documented. However, many of these observations are restricted to cultured fish populations. Due to the expanding host and geographical ranges of B. acheilognathi, the importance of the parasite to wild fish populations requires further assessment and documentation. This is an important consideration in view of declining global biodiversity and the growing conservation efforts to protect aquatic environments.

Comparative studies are needed to understand differences in species susceptibility and disease potential in newly infected hosts and the consequences of the parasite in new environments. Sub lethal effects of the parasite on fish growth, fitness, fecundity, behavior or tolerance to environmental changes may also hold important ecological implications. The physiological and bioenergetics costs of the parasite under natural conditions also require clarification. This information is necessary to provide better understanding of future disease risks and to evaluate the role of this introduced parasite on the health and stability of fish populations.

Gaps in knowledge and research needs. Recent work on B. acheilognathi in Africa 74 and in China 82, 83 shows that our understanding of the distribution, biogeography and systematics of this worm is still fragmentary. We still do not understand its host associations and why some hosts are susceptible and others not. We also need to develop a clearer understanding of how it affects natural populations, as well as early warning systems related to its invasiveness. Parasitologists will need to work closely with fisheries biologists and local and national agencies to develop comprehensive strategies to monitor natural fish populations.

References. El artículo incluye unas 150 citas bibliográficas que no se insertaron por su larga extensión. Los interesados pueden solicitarlas a stanveer96@gmail.com