Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cardiología

On-line version ISSN 1850-3748

Rev. argent. cardiol. vol.83 no.3 Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires June 2015

OPINIÓN ARTICLE

Medical Professionalism, Models of regulation and Professional autonomy

El profesionalismo médico, los modelos de regulación y la autonomía profesional

Raul a. BorraccimtsaC, Victor m. MauromtsaC

The aim of this article is to analyze the theoretical bases underlying medical professionalism and professional autonomy and, at the same time, to define the necessary conditions to implement a model of self-regulated medical activity.

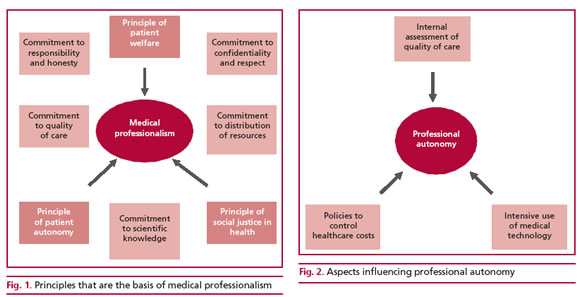

The term medical professionalism is used in different ways. In a broad sense, medical professionalism includes three key dimensions: expert knowledge, self-regulation of the profession and the obligation to subordinate the self-interest of the practitioner to the patient’s needs, interests and autonomy. (1) Altruism, empathy, humanism and high ethical and moral standards are some of the elements mentioned to describe medical professionalism. (2) However, making lists of desirable professional characteristics and behaviors is not sufficient to fully capture the social functions of medical professionalism. Although somehow more abstract but with a broader framework, medical professionalism can be defined as a system of normative beliefs about how best to organize and deliver health care. (3) Professionalism must be based on three principles: the principle of patient welfare, the principle of patient autonomy and the principle of social justice for the fair distribution of health care resources (Figure 1). These principles are supported by a set of commitments that physicians must subscribe to: commitment to professional responsibility and honesty with patients, commitment to patient confidentiality and respect, commitment to improving quality of care based on scientific knowledge, and commitment to promoting fair distribution of health care resources within the society.

A model of professional activity regulation can be defined as the mechanism used to establish the characteristics of medical practice and the technical standards to achieve. This model includes the procedures for job market insertion by educating, licensing and certifying new physicians, and, in this way, monitoring the competence for medical practice. The structure of the job market, from public to private health care systems, and the payment method, either salary or payment for service or practice, constitute other variables related and included in the regulation models.

Based on these characteristics, the scope of control models ranges from full state regulation to physician self-regulation, and includes state-sanctioned or state-approved self-regulation, in which the institutions in charge of formulating and implementing the regulation mechanism are composed by the own physicians, who are supported and consented by the State. (4) Within the different models of professional regulation, physicians play the role of health care providers for the State, trade unions and private institutions acting as financiers. In addition, the State may decide whether or not to give the professional groups the capacity of self-regulating their own practice. The State, through its agencies, can determine the number of physicians and their geographic distribution, decide their participation in health care institutions and determine their payment. On the contrary, when the participation of the State is not so broad, financiers and private producers define the regulation model imposed on physicians. An insufficiently perceived aspect is that physicians have a predominant role in pducing health care services due to their technical capabilities for operative decision-making. To a large degree, financing agents depend mostly on physicians as direct producers, as only physicians are legally and socially authorized to make technical decisions concerning health care services. Thus, due to their professional education, physicians enjoy a “technical autonomy” which gives them the capability of negotiating with the funding system.

The principle of medical autonomy is related with professionalism at different levels. Due to the characteristics of the medical profession, physicians need a high level of individual autonomy to control the terms and peculiarities of their practice. As a solitary actor, and in an ideal way, a physician usually decides the time and manner he dedicates a patient, as well as the tests ordered and the treatments indicated. Although autonomy may be revealed as a privilege among physicians, it should also be corresponded with extreme professionalism and ethical integrity. In this sense, a correct definition of professionalism and autonomy is the fundamental premise to accept that physicians themselves should converge, define, declare and trans-mit the technical competences and ethical values that govern medical practice. This confluence of actions is usually summarized in the models of self-regulation that are traditionally proposed by medical colleges.

Obviously, professional autonomy can only be maintained if physician activities and decisions are subjected to the critical evaluation of other colleagues and even to the patients' opinions. A collegial model can only assume the responsibility of medical practice regulation based on a contract between peers. The collegial model, in return for its self-regulating priv-ileges, undertakes to act as a reliable guarantor for the competence and conduct of each of its members. For this reason, a collegial structure cannot work without a clear moral influence on the behavior and competence of its members or without the capability of judging their actions. The United Kingdom, for ex-ample, endorsed the collegial model of self-regulation of medicine that endured for 150 years until the mid 90s, when this model collapsed due to several ethical scandals in medical practice. (5) Undoubtedly, the balance favoring "good" over "bad" physicians is not enough to maintain the respectability of a collegial system within the society. A few bad public examples usually weigh more than many solitary good medical attitudes.

Professional autonomy can be analyzed from the point of view of three different areas. (6) (Figure 2) The first area refers to the influence of health care policies on the control of health care costs that limits the professional autonomy of physicians in their daily practice, and includes: low salaries as a consequence of an overpopulation of physicians and, probably, of unfair distribution of economic resources; the imposi-tion of limited consultation time; the implementation

of per capita reimbursements and quotas for practices; the obligation to prescribe generic drugs of doubtful quality; the restrictions for referring patients to specialist physicians, and the inequality to access screen-ing tests and treatments depending on the health in-surance coverage. The second aspect of professional autonomy fits within the change of paradigm that goes from traditional clinical care to knowledge-based or evidence-based clinical care, usually supported by an intensive use of medical technology. Patients become more demanding due to higher access to information and to "provider-induced demand" which increases the pressure to use more diagnostic and therapeutic technology, impairing the physician-patient relationship, together with the temptation provoked by incentives offered by drug companies and the emergence of sub-specialists whose opinions are difficult to refute. (7) Finally, the third factor of interest in medical autonomy is the insufficient internal assessment of qual-ity of care and good professional practice performed by scientific societies, colleges and heath care entities controlled by unions. This area involves certification and recertification; regulation of the number of general practitioners and specialists and their geographical distribution; honest discussion of conflicts of interest; evidence-based use of innovative techniques in daily practice and fair distribution of resources; promo-tion of quaternary prevention to attenuate excessive medical intervention; critical evaluation of colleagues in ethical tribunals; reporting of medical errors; com-mitment to promote equal access to medicine for all persons; scientific disclosure to educate the population and the acknowledgement of patients' opinion as the final subjects of medical activity.

Professionalism is nowadays a matter of analysis worldwide and a global project trying to protect not only the medical profession but specially the population health from the indifference of social policies or inequality generated by economic relapses. (8-13) Nevertheless, professional autonomy is often described as a claim of professionals serving primarily their own interests, or else as a tool to construct a standard of professional practice to benefit both patients and medical activity. (6)

In practice, a physical normative structure must assume the responsibility of monitoring that the standards of medical professionalism listed above are accomplished. The regulatory dispersion of the differ-ent aspects related to professional practice in different agencies and decision makers complicates the compre-hensive treatment of medical practice. The participa-tion of physicians, organized according to the princi-ples of professionalism either in a collegial model or in any other system established by the law, will ensure the quality of care for the population.

In conclusion, medicine is a moral task, a profes-sion whose members adhere to a set of principles of respect for others, honesty and professional compe-tence. (14) These principles are the bases of medical professionalism and the foundation of the social con-tract between medicine and society.

Conflicts of interest

The authors belong to the Board of Directors of the Argenti-ne College of Cardiology.

REFERENCES

1. Ludmerer KM. Instilling professionalism in medical education. JAMA 1999;282:881-2.

2. Wynia MK, Latham SR, Kao AC, Berg J W, Emanuel LL. Medical professionalism in society. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1612-6.

3. Wynia MK, Papadakis MA, Sullivan WM, Hafferty F W. More than a list of values and desired behaviours: a fundamental under-standing of medical professionalism. Acad Med 2014;89:712-4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000212

4. Nigenda G, Machado MH. Models for physicians' professional reg-ulation in Latin America and theoretical elements for its analysis. Cad Sude Publ 1997;13:685-92.

5. Dixon-Woods M, Yeung K, Bosk CL. Why is U.K. medicine no lon-ger a self-regulating profession? The role of scandals involving "bad apple" doctors. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:1452-9.

6. Hoogland J, Jochemsen H. Professional autonomy and the norma-tive structure of medical practice. Theor Med Bioeth 2000;21:457-75.

7. Doval HC. El profesionalismo médico y las prácticas con la industria que crean conflictos de intereses. Rev Argent Cardiol 2008;76:417-22.

8. ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine; ACPA-SIM Foundation. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:243-6.

9. Tyssen R, Palmer KS, Solberg IB, Voltmer E, Krank E. Physi-cians' perceptions of quality of care, professional autonomy, and job satisfaction in Canada, Norway, and the United States. BMC Health Services Research 2013;13:516. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-516

10. Clyde JW, Domenech Rodriguez MM, Geiser C. Medical profes-sionalism: an experimental look at physicians' Facebook profiles. Med Educ Online 2014;19:23149. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.23149

11. Lombarts KMJMH, Plochg T, Thompson CA, Arah OA, on behalf of the DUQuE Project Consortium (2014) Measuring Professional-ism in Medicine and Nursing: Results of a European Survey. PLoS ONE 2014;9(5):e97069. doi:10.1371/journal.pone. 0097069

12. Chen J, Xu J, Zhang C, Fu X. Medical professionalism among clinical physicians in two tertiary hospitals, China. Social Science & Medicine 2013;96:290e296.

13. Bustamante E, Sanabria A. Spanish adaptation of The Penn State College of Medicine Scale to assess professionalism in medical students. Biomédica 2014;34:291-9. doi: 10.7705/biomedica. v34i2.1807

14. Wojtczak H. Profesionalismo médico: una problemática global. Educ Med 2006;9:144-5.