Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Boletín de la Sociedad Argentina de Botánica

versión On-line ISSN 1851-2372

Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. vol.45 no.3-4 Córdoba jul./dic. 2010

ANATOMÍA Y MORFOLOGÍA

Fruit anatomy of species of Solanum sect. Torva (Solanaceae)

Franco E. Chiarini 1, Natalia R. Moyetta & Gloria E. Barboza

1 Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal (CONICET-UNC) C.C. 495, 5000 Córdoba, Argentina. Phone (Fax) +54 351 4331056

E-mail: franco.e.chiarini@gmail.com

Summary: The mature fruits of 10 South American species of Solanum sect. Torva were studied. Cross and longitudinal microtome sections, stained with astra blue/basic fuchsin, were made for microscopic examination. All species present an epidermis formed by a unistrate layer of small, isodiametric cells, with dense content and cellulosic walls. Immediately below, a hypodermis is always found, consisting of a well-defined layer of lignified cells with a single calcium oxalate crystal occupying the whole lumen of each cell. This is followed by one layer of cellulosic, isodiametric cells with dense cytoplasm and then several collenchymatous layers, sometimes with sclerified cell walls. The mesocarp comprises two zones histologically differentiated: an external one (formed by regular, vacuolated, medium-sized cells with small intercellular spaces), and an internal one, commonly juicy, and developing proliferations among the seeds. The fruits analyzed are alike, and despite some particularities, they can be classified as berries in the conventional sense. All the traits examined agree with the ornithochorous dispersal syndrome. The homogeneity in fruit traits may be due to shared habit, habitat and sexual system.

Key words: Berry; Dispersal syndrome; Pericarp; Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum; South America.

Resumen: Anatomía del fruto en especies de Solanum sect. Torva (Solanaceae). Se estudiaron los frutos maduros de 10 especies sudamericanas de Solanum sect. Torva. Se examinaron en microscopio cortes microtómicos transversales y longitudinales teñidos con azul astral/fucsina básica. Todas las especies presentaron una epidermis unistrata de células pequeñas, isodiamétricas, de contenido denso y paredes celulósicas. Inmediatamente por debajo se encontró siempre una hipodermis, formada por una capa bien definida de células lignificadas con un cristal de oxalato de calcio en el lúmen de cada célula. A continuación se halló otra capa de celulas isodiamétricas, celulósicas, de contenido denso, y luego varias capas de colénquima, en ocasiones con paredes esclerificadas. El mesocarpo presentó dos zonas histologicamente diferenciadas: una externa (formada por células regulares, vacuoladas, de tamaño medio y espacios intercelulares pequeños) y una interna, comúnmente jugosa y que prolifera entre las semillas. No obstante algunas particularidades, los frutos analizados son similares entre sí, y se clasificaron como bayas en sentido convencional. Todos los rasgos analizados concuerdan con el síndrome de dispersión ornitócoro. La homogeneidad en los caracteres puede deberse al hábito, hábitat y sistema sexual compartidos.

Palabras clave: Baya; Síndrome de dispersión; Pericarpio; Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum; Sudamérica.

INTRODUCTION

With 1250-1700 species growing in all kinds of habitats, Solanum L. is the largest genus in Solanaceae and one of the 10 most species-rich genera of Angiosperms (Weese & Bohs, 2007). Within this genus, the Leptostemonum clade (or "spiny Solanums" clade) is the largest monophlyletic group, embracing the ca. 450 species traditionally placed in Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum (Dunal) Bitter (Bohs, 2005; Weese & Bohs, 2007). Notable representatives of the clade or subgenus are edible species like S. melongena L. (eggplant) and S. quitoense Lam. (naranjilla or lulo), weedy or invasive species like S. viarum Dunal (tropical soda apple), S. elaeagnifolium Cav. (silverleaf nightshade), S. carolinense L. (horsenettle), and S. rostratum Dunal (buffalo bur, bull thistle or Texas thistle), or ornamental plants such as S. mammosum L. (apple of Sodom, cow's udder or nipple fruit) and S. capsicoides All. (cockroach berry). In addition, some species of the Leptostemonum clade have been the subject of several studies due to their andromonoecy or functional dioecy (Wakhloo, 1975a, b; Anderson, 1979; Dulberger et al., 1981; Coleman & Coleman, 1982; Solomon, 1987; Diggle, 1991, 1993).

One of the most important and better-defined groups within subgen. Leptostemonum is section Torva Nees. It includes ca. 40-50 species, mostly South American, which concentrated in the Andes from Colombia to northern Argentina and southeastern Brazil (Whalen, 1984; Nee, 1999). The species of this section are weakly andromonoecious or hermaphrodite shrubs or small trees 2-10 m high, characterize by having entire or repand ovate leaves, several-branched inflorescences and corollas usually rotate or pentagonal. They are typical of secondary vegetation and grazed lands throughout the montane Neotropics (Whalen, 1984). The outstanding representative of sect. Torva is S. torvum Sw. (Turkey berry or devil's fig), originally from Mexico and Central America, but widely introduced in the Old World tropics (Welman, 2003).

Despite the particular importance of section Torva (and the relevance of subgen. Leptostemonum in general), some aspects of its biology, such as fruit structure, remain unexplored. This is unfortunate because fruits are one of the most conspicuous traits of seed plants. They are the mechanism by which seeds are dispersed, and also constitute a main systematic character. Knapp (2002a) proposed that within subgen. Leptostemonum, fruits can be not only fleshy, but also hard berries or variously modified non-capsular dehiscent fruits. Nevertheless, this classification of fruit types is based mostly on macroscopic features (colour, size, dehiscence) since studies focusing on the anatomical / histological point of view are scanty. Thus, in order to gain comprenhensive knowledge of the fruit anatomy within the species of subgen. Leptostemonum, and to evaluate probable taxonomical and evolutionary incidences, we developed a carpological analysis in members of different sections of this subgenus. As a result, some groups, such as the Argentine representatives of sect. Melongena (sensu Nee, 1999), revealed to be very heterogeneous concerning fruit traits (Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a), supporting the paraphyly of such section (Levin et al., 2006). Additionally, fruits of sect. Acanthophora species showed to be notably diverse despite the monophyly of the section (Levin et al., 2005; Chiarini & Barboza, 2009). In this study, we present results in species of sect. Torva in order to define their fruit type as a help to the understanding of the relationship among structure, function and dispersal syndrome. These anatomical analyses will contribute to the last phylogenetic studies performed in Solanum (Bohs, 2005; Levin et al., 2005, 2006; Martine et al., 2006), which explain evolutionary patterns and relationships among the clades considering synapomorphies of DNA sequences, but neglecting the role of morphology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ten wild species were analyzed. The following are the voucher data of the material studied:

Solanum albidum Dunal. BOLIVIA. La Paz. Nor Yungas, 16º 13' 34'' S, 67º 47' 12''W, 25-IV-2006, Barboza et al. 1833 (CORD); Sud Yungas, near Circuata, 27-IV-2006, Barboza et al. 1853 (CORD).

Solanum asperolanatum Ruiz et Pav. BOLIVIA. Santa Cruz. From Comarapa to Laguna Verde, 30-IV-2006, Barboza et al. 1902 (CORD).

Solanum bolivianum Rusby. BOLIVIA. La Paz. From Quime to Inquisivi, 16º 57' 01'' S, 67º 11' 27''W, 28-IV-2006, Barboza et al. 1856 (CORD).

Solanum bonariense L. ARGENTINA. Entre Ríos. Gualeguaychú, 33º39'28''S, 58º43'24''W, 28-VII-2005, Chiarini 640 (CORD).

Solanum consimile Morton. BOLIVIA. Tarija. Near Aguas Blancas, 30-IX-2001, Barboza et al. 279 (CORD); La Mamora, 22º14' 59''S, 64º34' 55''W, 5-X-2001, Barboza et al. 307 (CORD).

Solanum guaraniticum St. -Hil. ARGENTINA. Corrientes. Santo Tomé, 7-I-2002, Chiarini 532 (CORD); Misiones. Capital, 27º23'29''S, 55º53'35''W, 7-XII-2002, Barboza et al. 404 (CORD); Gral. San Martín, 26º59'08''S, 54º41'36''W, 28-III-2004, Barboza et al. 922 (CORD).

Solanum paniculatum L. BRAZIL. São Paulo. Faz. São Martinho, Síncroton, 2-VII-2003, Marcondes et al. s.n. (CORD 1029); PARAGUAY. Caazapá. Entrance to the city, 26º 11'08''S, 5º6 22'14''W, 13-XII-2002, Barboza et al. 500 (CORD).

Solanum scuticum M. Nee. BRAZIL. São Paulo. Campinas, Souzas, 28-VI-2003, Marcondes et al. s.n. (CORD 1030); near Salto, 29-VI-2003, Barboza et al. s.n. (CORD 1065); Rio de Janeiro. Distrito Federal, 17-VII-2003, Barboza et al. 801 (CORD).

Solanum toldense Matesevach & Barboza. ARGENTINA. Salta. Santa Victoria, 22º 21' 53'' S, 64º 43' 20''W, Barboza et al. 281 (MCNS, CORD); Santa Victoria, 29-XI-2004, Barboza et al. 1086 (CORD)

Solanum variabile Mart. BRAZIL. Rio Grande do Sul. São Francisco de Paula, 29º19'31''S, 50º07'22''W, 23-XI-2003, Mentz et al. 266 (CORD, ICN).

For microscopic examination, whole or cut up ripe fruits were preserved in a formaldehyde-acetic acid-ethanol mixture, dehydrated then in a 50 to 100 % ethanol series, and embedded in Paramat® resin. Cross and longitudinal microtome sections 10-12 μm thick were stained with a 1% astra blue solution in a 1% water/basic fuchsin solution in 50º ethanol (Kraus et al., 1998). In addition, temporary slides were made using fluoroglucin and hydrochloric acid in order to verified the presence of lignin (D'Ambrogio de Argüeso, 1986).

The specimens were visualized using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope equipped with light and differential-interference contrast (DIC). The images were captured with a digital camera assembled to the microscope.

RESULTS

According to Knapp (2002a), the fruits of Solanum sect. Torva studied here are berries in the conventional sense. They are simple fruits with an indehiscent pericarp, containing many seeds embedded in a solid fleshy mass, supported by an exocarp less than 2 mm thick. All of them are spherical, small- to medium-sized, varying from 0.7 cm (S.consimile) to 1.5 cm (S. paniculatum) in diameter. When mature, they are of a single colour, namely red or orange-red (most of the species), yellow (S. scuticum), black or brownish (S. toldense), or dark green (S. bolivianum and S. albidum). In S. asperolanatum, deciduous stellate hairs are present in the epidermis, especially at early stages, whereas the remaining species have a glabrous pericarp. Details of the anatomy of each species are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Macroscopic and anatomical fruit features of the ten species of Solanum sect. Torva studied.

Exocarp

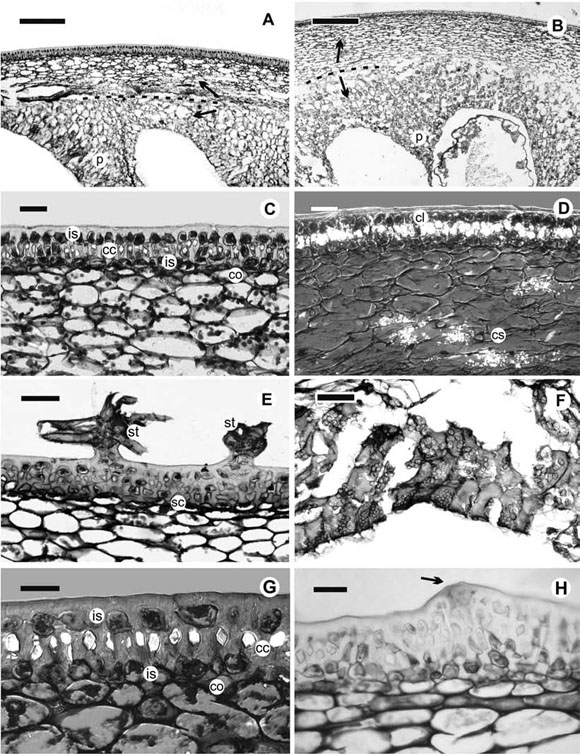

The cuticle is usually thick and smooth (e.g. S. consimile, Fig. 1 C; S. guaraniticum, Fig. 1 G), exceptionally, somewhat undulate in S. scuticum. In all species, cuticular wedges are present among the epidermal cells. Ventilation clefts are only found in S. paniculatum (Fig. 1 H), while stomata are lacking in all cases.

In all cases, the epidermis consists of a unistrate layer of small, isodiametric cells, with dense content and cellulosic walls (Fig. 1 C, E, G, H).

Immediately below the epidermis, a hypodermis is differentiated, which consists of a well-defined layer of lignified cells with a single prismatic calcium oxalate crystal occupying the whole lumen of each cell (Fig. 1 C, D); the hypodermis is followed by one layer of cellulosic, isodiametric cells with dense cytoplasm, and then several collenchymatous layers, with sclerified cell walls in some species (i.e. S. asperolanatum, Fig. 1 E). The cells containing the crystals have an irregular shape (Fig. 1 G). Both, the epidermis and the hypodermis constitute the exocarp, which generally has layers that gradually decrease their degree of lignification from the outside to the inside of the fruit.

Usually, when the fruit is immature, the cell layers located below the crystalliferous layer have chloroplasts and chromoplasts. When the fruit matures, the chloroplasts disappear and the cells become compressed. A collenchyma is always present, in which the number of layers and the degree of lignification vary according to the species (Fig. 1 C, E, G; Table 1).

Fig. 1. Photomicrographs of longitudinal sections in fruits of Solanum sect. Torva species. A. Pericarp of S. consimile, bar = 250 μm. Dotted line and arrows show the division of zones of the mesocarp. B. Pericarp of S. toldense, bar = 500 μm. Dotted line and arrows show the division of zones of the mesocarp. C. Exocarp of S. consimile, bar 50 = μm. D. Exocarp of S. consimile, taken with DIC, showing the cells with crystals and the crystal sands, bar = 50 μm. E. Exocarp of S. asperolanatum, showing the stellate hairs of the epidermis, bar = 100 μm. F. Internal zone of the mesocarp of S. albidum, showing the cells filled with grains, bar = 100 μm. G. Detail of the cells containing a crystal in the epidermis of S. guaraniticum, taken with DIC, bar = 50 μm. H. Epidermis of S. paniculatum, an arrow pointing to a ventilation cleft, bar = 50 μm. Abbreviations: cc = cells containing a crystal; cl = crystalliferous layer; co = collenchyma; cs = crystal sands; is = isodiametric cells; p = proliferations among the seeds; sc = sclerified collenchyma; st = stellate hairs.

Mesocarp

The mesocarp is formed by two zones histologically differentiated: an external one (immediately below the hypodermis), which has affinity for astra blue, and an internal one, dyed with basic fuchsin (Fig. 1 A, B). The external zone consists of 8-16 layers of regular, vacuolated, medium-sized cells with small intercellular spaces. The internal zone is commonly juicy, and develops proliferations among the seeds (Fig. 1 A, B). The cells are large, with dense content filled with grains (probably starch, Fig. 1 F); the cellulosic walls of these cells disorganize and their cellular content is released to the locules, producing a mucilage-like substance that surrounds the seeds in the ripe fruit.

In some species, the two zones have a few layers and are not clearly defined. The thickness of each zone varies according to the species (Table 1). In S. consimile and S. scuticum, the mesocarp is clearly divided into two zones, crystal sands are present in the proliferations among the seeds or on the limit between both zones (Fig. 1 D).

Endocarp

No specific particularities were observed in the endocarp. This layer, which is very difficult to observe due to its delicate structure, is uniseriate and lacks stomata in all cases.

DISCUSSION

According to van der Pijl (1982), the colour of the fruits can be attributed to the dispersal syndrome, and brightly coloured ones would be more attractive to birds (Edmonds & Chweya, 1997). This could be the case of the majority of the species analyzed here, whose fruit colour is red or orange. Cipollini et al. (2002) described a pattern in which small, red and black fruits with high nutrient, nontoxic and watery content differ from large, yellow fruits with low nutrient, toxic, high dry matter content. Nevertheless, colour seems to be independent of tissue types or morpho-anatomical structures: the fruits analyzed in this paper are anatomically resembling but show different colours.

According to Dottori (1995, 1998) and Dottori & Cosa (1999, 2003), the pericarp comprises three clearly distinguishable zones: the exocarp, the mesocarp, and the endocarp. These authors described an ontogenetic pattern in some species of Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum, apparently the same as the species studied here.

As in other berry-bearing species of Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum (Dottori, 1998; Dottori & Cosa, 1999; Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a, 2009), the epidermis of sect. Torva species is formed by simple cells: modification of shape, pit or degree of lignification, as those found in species with other fruit types (Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a, 2009), were not detected.

In S. paniculatum, ventilation clefts were observed, though these structures were not seen in the rest of the species. Similar clefts have been mentioned for Capsicum (Dave et al., 1979), for S. glaucophylum Desf. (Dottori, 1995) and for one Leptostemonum species, S. juvenale Thell. (Dottori, 1998), but their function remains unexplained.

The hypodermis, essentially constituted by collenchyma, is present in all the species studied, but there is a slight variation in the number of layers and degree of lignification. The function of this layer would be to provide mechanical support (Roth, 1977) since collenchymatous hypodermis is common in fruits with a thick outer rind, such as berries and drupes of some species of Ribes, Berberis and Paris (Roth, 1977), and even berries of some Solanum (Klemt, 1907; Roth, 1977; Valencia, 1985; Dottori & Cosa, 1999).

The tissue we referred to as "sclerified collenchyma" is a layer formed by hypodermal cells resembling the outline of a true collenchyma, but with their walls impregnated with lignin. The thicker this layer, the harder the consistency of the fruit is. Thus, the sclerified collenchyma may be a structure that makes the fruits harder and more resistant to deformation, perhaps acting as a defence against phytophagous insects. Indeed, fruit traits are typically interpreted in relation to vertebrate dispersion and consumption, while the also important insect and microbial attack is ignored (Tewksbury, 2002). The invariable presence of a subepidermic layer of crystals, embedded on cells with lignified walls, would also function as a protection against fungal or insect attack.

The crystal layer is not exclusive of sect. Torva since several species of sect. Melongena also show a similar layer (Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a). Nevertheless, in sect. Melongena the cells containing the crystals are fibres with a defined shape and two notable pits, whereas in members of sect. Torva the cells with crystals have an irregular outline. In the former, the fibres seem to be related to the dehiscence mechanism, whereas fruits of sect. Torva species are indehiscent.

Crystal sands in the placentas and on the limit between the two zones of the mesocarp in S. consimle and S. scuticum are another type of mineral deposition, different from the crystals embedded on cells, and they are not exceptional in Solanaceae. They have been reported for Physalis (Valencia, 1985) and other species of Solanum (Dottori & Cosa, 1999). There are several explanations for the presence of the different mineral deposits of calcium oxalate. They would provide multiple benefits to different plant organs, for example, a primary mechanism for controlling the excess of calcium (Franceschi & Horner, 1980; Webb, 1999), a reinforcement of vascular bundle cells (Zindler-Frank, 1995), a hardening of the cell layers within the seed coat (Webb & Arnott 1982), a structural reinforcement analogous to cell wall sclerification in epidermal or subepidermal tissues (Brubaker & Horner, 1989), a probable role in anther dehiscence (Horner & Wagner, 1980), or a defence against herbivores (Sakai et al., 1972; Thurston, 1976). Nevertheless, none of these explanations has been applied for the mineral depositions in fruits. We tend to think that they are a simple sub-product of metabolic activity.

The spongy tissue, described in several species of the subgenus Leptostemonum, and especially in species of sect. Acanthophora (Miller, 1969; Nee, 1991; Chiarini & Barboza, 2009), is absent from the species here studied. Instead, species of sect. Torva develop a two-zoned mesocarp with proliferations among the seeds, probably in response to another habit, habitat and means of dispersal. Regarding the pulp, both the placenta and, especially the pericarp, contribute to form it, which coincides with the pattern already described (Garcin, 1888; Murray, 1945). It is the same case of Physalis peruviana L. (Valencia, 1985) and other Solaneae (Filippa & Bernardello, 1992). Instead, in Solanum lycopersicum L. (sub nom. Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) only the placentas are responsible for the formation of the pulp (Murray, 1945; Roth, 1977). The first pattern is the most commonly observed whereas the second one is peculiar to S. lycopersicum.

Another particularity observed in the mesocarp of sect. Torva species, is the absence of stone cells or sclerosomes, which are widely present in many sections of Solanum and in related genera (Hunziker, 2001).

As well as noticed in several Solanaceae, the fleshy or juicy fruits examined here show a disorganisation of the inner mesocarp and the endocarp. In S. lycopersicum, fruit softening by cell disassembly is caused by the activity of polygalacturonase and pectate lyases, which catalyse modifications to the pectin fraction of the cell walls (Marín-Rodríguez et al., 2002; Seymour et al., 2002). Pectate lyase sequences have been reported for several species from different families (Medina-Escobar et al., 1997; Marín-Rodríguez et al., 2002). Different levels of expression of such genes may be responsible for the formation of the juicy zone and the firm zone in the mesocarp of the species studied here.

In some groups of Solanum, berries easily detach from the pedicel when they ripe. In the nightshades (Solanum sect. Solanum), for example, berries can fall to the ground and seeds germinate "in situ", or fruits can be eaten by birds (Burgert et al., 1973; Edmonds & Chweya, 1997). Species of other sections abscise at the base of the pedicel, releasing the fruit and the pedicel as a unit (Whalen, 1979; Knapp, 2002b). Nevertheless, none of these mechanisms has been observed in the species studied: fruits are retained on the plant until they dry, rot or are consumed.

Considering that direct observation of the dispersion is seldom possible, fruits are usually classified into different dispersal syndromes according to their morphological characters, being van der Pijl's (1982) criterion most commonly followed. Thus, the small, red/orange, few-seeded, somewhat juicy fruits produced by the species of sect. Torva, berries in the traditional sense (Spjut, 1994; Knapp, 2002a) would be presumably ornithochorous, since all the features agree in general with the syndrome of bird diaspores (van der Pijl, 1982). In fact, consumption by bats and diurnal birds has been documented for S. granulosoleprosum Dunal (Cáceres & Moura, 2003), a species of subgen. Brevantherum that has similar habit, inflorescence structure, and external fruit appearance.

From the evolutionary point of view, sect. Torva displays some particularities. On the one hand, the section is characterized by many flowered, manybranched, corymbose or paniculate cymes, with mostly hermaphrodite flowers (Child, 1979; Whalen, 1984). Symon (1979) suggested that these kinds of inflorescences can probably be considered primitive. On the other hand, the fruits, which are homogeneous among the species studied, exhibit features considered derived, like the elaborated placentas (Nee, 1986; Chiarini & Barboza, 2007b) and the hypodermal lignified cells with a crystal, probably derived from the simple parenchymatous cells of the typical berry. The derived characters make the berries of sect. Torva a slightly different from the classical berry or the berries of other Leptostemonum species (Miller, 1969; Dottori & Cosa, 1999, 2003; Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a). This mix of primitive and derived traits is reflected by molecular phylogeny, since sect. Torva has a halfway position in the phylogenetic tree of Levin et al. (2006).

Hence, fruit structure is not uniform in the genus Solanum. It is homogeneous within sect. Torva, whereas in other sections, such as Acanthophora and especially Melongena, it is more heterogeneous, and diverse fruit types can be found (Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a, 2009). Fruit traits seem to respond rapidly to selection constraints on the dispersal syndromes (Nee, 1986; Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a, b). We tend to think that similarities in fruit of sect. Torva can result from ecological conditions, for instance, a similar habitat or ecological niche. In addition, andromonoecy, which has influence on fruits traits like size and seed number (Whalen & Costich, 1986; Chiarini & Barboza, 2007a, b), is weak or not found in the species researched.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Consejo Nacional de Investicaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología de Córdoba (Argentina), SECyT (UNC, Argentina ), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil) and Myndel Botanica Foundation (Buenos Aires, Argentina) for financial support.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. ANDERSON, G. J. 1979. Dioecious Solanum species of hermaphroditic origin is an example of a broad convergence. Nature 282: 836-838. [ Links ]

2. BOHS, L. 2005. Major clades in Solanum based on ndhF sequence data. In: HOLLOWELL, V., R. KEATING, W. LEWIS, & T. CROAT (eds.), A festschrift for William D'Arcy, Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 104: 27-50. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, Missouri. [ Links ]

3. BRUBAKER, C. L. & H. T. HORNER. 1989. Development of epidermal crystals in leaflet of Stylosanthes guianensis (Leguminosae; Papilionoideae). Canad. J. Bot. 67: 1664-1670. [ Links ]

4. BURGERT, K. L., O. C. BURNSIDE & C. R. FENSTER. 1973. Black nightshade leaves its mark. Farm, Ranch Home Quart., 8-10 (not seen, taken from Edmonds & Chweya, 1997). [ Links ]

5. CÁCERES, N. C. & M. O. MOURA. 2003. Fruit removal of a wild tomato, Solanum granulosoleprosum Dunal (Solanaceae), by birds, bats, and non-flying mammals in an urban Brazilian environment. Revista Brasil. Zool. 20: 519-522. [ Links ]

6. CHIARINI, F. & G. E. BARBOZA. 2007a. Anatomical study of different fruit types in Argentine species of Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum (Solanaceae). Anales Jard. Bot. Madrid 64: 165-175. [ Links ]

7. CHIARINI, F. & G. E. BARBOZA. 2007b. Placentation patterns and seed number in fruits of South American Solanum subgen. Leptostemonum (Solanaceae) species. Darwiniana 45: 163-174. [ Links ]

8. CHIARINI, F. & G. E. BARBOZA. 2009. Fruit anatomy of species of Solanum sect. Acanthophora (Solanaceae). Flora 204: 146-156. [ Links ]

9. CHILD, A. 1979. A review of branching patterns in Solanaceae. In: HAWKES, J. G., R. N. LESTER & A. J. SKELDING (eds.), The biology and taxonomy of the Solanaceae, Linnean Society Symposium Series 7, pp. 345-356. The Linnean Society of London, London. [ Links ]

10. CIPOLLINI, M. L., L. BOHS, K. MINK, E. PAULK & K. BÖHNING-GAESE. 2002. Secondary metabolites of ripe fleshy fruits. Ecology and phylogeny in genus Solanum. In: LEVEY, D. J., W. R. SILVA & M. GALETTI (eds.), Seeddispersal and frugivory. Ecology, evolution and conservation, pp. 111-128. CAB International Publishing, Wallingford, Oxforshire. [ Links ]

11. COLEMAN, J. R. & M. A. COLEMAN. 1982. Reproductive biology of an andromonoecious Solanum (S. palinacanthum Dunal). Biotropica 14: 69-75. [ Links ]

12. D'AMBROGIO DE ARGÜESO, A. M. 1986. Manual de técnicas en histología vegetal. Ed. Hemisferio Sur, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

13. DAVE, Y. S., N. D. PATEL & K. S. RAO. 1979. Developmental and anatomical studies in the pericarp of Capsicums. Flora 168: 263-275. [ Links ]

14. DIGGLE, P. K. 1991. Labile sex expresion in andromonoecious Solanum hirtum: pattern of variation in floral structure. Canad. J. Bot. 69: 2033-2043. [ Links ]

15. DIGGLE, P. K. 1993. Developmental plasticity, genetic variation, and the evolution of andromonoecy in Solanum hirtum (Solanaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 80: 967-973. [ Links ]

16. DOTTORI, N. 1995. Desarrollo y estructura de fruto y semilla en Solanum sect. Cyphomandropsis (Solanaceae) de Argentina. Kurtziana 24: 83-104. [ Links ]

17. DOTTORI, N. 1998. Anatomía y ontogenia del fruto y semilla de Solanum juvenale Thell. (Solanaceae). Kurtziana 26: 13-22. [ Links ]

18. DOTTORI, N. & M. T. COSA. 1999. Anatomía y ontogenia de fruto y semilla en Solanum hieronymi (Solanaceae). Kurtziana 27: 293-302. [ Links ]

19. DOTTORI, N. & M. T. COSA. 2003. Desarrollo del fruto y semilla en Solanum euacanthum (Solanaceae). Kurtziana 30: 17-25. [ Links ]

20. DULBERGER, R., A. LEVY & D. PALEVITCH. 1981. Andromonoecy in Solanum marginatum. Bot. Gaz. 142: 259-266. [ Links ]

21. EDMONDS, J. M. & J. A. CHWEYA. 1997. Black nightshades. Solanum nigrum L. and related species, pp. 1-113. IPGRI, Gatersleben, Germany. [ Links ]

22. FILIPPA, E. M. & L. M. BERNARDELLO. 1992. Estructura y desarrollo del fruto y semilla en especies de Athenaea, Aureliana y Capsicum (Solaneae, Solanaceae). Darwiniana 31: 137-150. [ Links ]

23. FRANCESCHI, V. R. & H. T. HORNER. 1980. Calcium oxalate crystals in plants. Bot. Rev. 46: 361-428. [ Links ]

24. GARCIN, M. A. G. 1888. Sur le fruit des Solanées. J. Bot. 2 : 108-115. [ Links ]

25. HORNER, H. T. & B. L. WAGNER. 1980. The association of druse crystals with the developing stomium of Capsicum annuum (Solanaceae) anthers. Amer. J. Bot. 67: 1347-1360. [ Links ]

26. HUNZIKER, A. T. 2001. Genera Solanacearum. The genera of Solanaceae illustrated, arranged according to a new system. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.-G, Ruggell. [ Links ]

27. KLEMT, F. 1907. Über den bau und die Entwicklung einiger Solanaceenfrüchte. Inaugural Diss., 1-35. [ Links ]

28. KNAPP, S. 2002a. Tobacco to tomatoes, a phylogenetic perspective on fruit diversity in the Solanaceae. J. Exp. Bot. 53: 2001-2022. [ Links ]

29. KNAPP, S. 2002b. Solanum section Geminata (Solanaceae). Fl. Neotrop. Monogr. 84. [ Links ]

30. KRAUS, J. E., H. C. DE SOUSA, M. H. REZENDE, N. M. CASTRO, C. VECCHI & R. LUQUE. 1998. Astra blue and basic fuchsin double staining of plant material. Biotech. Histochem. 73: 236-243. [ Links ]

31. LEVIN, R. A., N. R. MYERS & L. BOHS. 2006. Phylogenetics relationships among the "Spiny Solanums" Solanum subgenus Leptostemonum (Solanaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 93: 157-169. [ Links ]

32. LEVIN, R. A., K. WATSON & L. BOHS. 2005. A four-gene study of evolutionary relationships in Solanum section Acanthophora. Amer. J. Bot. 92: 603-612. [ Links ]

33. MARÍN-RODRÍGUEZ, M. C., J. ORCHARD & G. B. SEYMOUR. 2002. Pectate lyases, cell wall degradation and fruit softening. J. Exp. Bot. 53: 2115-2119. [ Links ]

34. MARTINE, C. T., D. VANDERPOOL, G. J. ANDERSON & D. H. LES. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships of andromonoecious and dioecious Australian species of Solanum subgenus Leptostemonum section Melongena: inferences from ITS sequence data. Syst. Bot. 31: 410-420. [ Links ]

35. MEDINA-ESCOBAR, N., J. CÁRDENAS, E. MOYANO, J. L. CABALLERO & J. MUÑOZ-BLANCO. 1997. Cloning molecular characterisation and expression pattern of a strawberry ripening-specfic cDNA with sequence homology to pectate lyase from higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 34: 867-877. [ Links ]

36. MILLER, R. H. 1969. A morphological study of Solanum mammosum and its mammiform fruit. Bot. Gaz. 130: 230-237. [ Links ]

37. MURRAY, M. A. 1945. Carpellary and placental structure in the Solanaceae. Bot. Gaz. 107: 243-260. [ Links ]

38. NEE, M. 1986. Placentation patterns in the Solanaceae. In: D'ARCY, W.G. (ed.), Solanaceae, biology and systematics, pp. 169-175. Columbia University Press, New York. [ Links ]

39. NEE, M. 1991. Synopsis of Solanum Section Acanthophora, A group of interest for glycoalkaloids. In: HAWKES, J. G., R. LESTER, M. NEE & N. ESTRADA (eds.), Solanaceae III, Taxonomy, Chemistry, Evolution, pp. 257-266. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. [ Links ]

40. NEE, M. 1999. Synopsis of Solanum in the New World. In: NEE, M., D. E. SYMON, R. N. LESTER & J.P. JESSOP (eds.), Solanaceae IV. Advances in Biology and Utilization, pp. 285-333. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. [ Links ]

41. ROTH, I. 1977. Fruit of Angiosperms. In: LINSBAUER, K. (ed.), Encyclopaedia of plant anatomy 10, pp. 1-675. Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin. [ Links ]

42. SAKAI, W. S., M. HANSON & R. C. JONES. 1972. Raphides with barbs and grooves in Xanthosoma sagittifolium (Araceae). Science 178: 314-315. [ Links ]

43. SEYMOUR, G. B., K. MANNING, E. M. ERIKSSON, A. H. POPOVICH & G. J. KING. 2002. Genetic identification and genomic organization of factors affecting fruit texture. J. Exp. Bot. 53: 2065-2071. [ Links ]

44. SOLOMON, B. P. 1987. The role of male flowers in Solanum carolinense: pollen donors or pollinator attractors? Evol. Trends Pl. 1: 89-93. [ Links ]

45. SPJUT, R. W. 1994. A systematic treatment of fruit types. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 70: 1-82. [ Links ]

46. SYMON, D. E. 1979. Sex forms in Solanum (Solanaceae) and the role of pollen collecting insects. In: HAWKES, J. G., R. N. LESTER & A. J. SKELDING (eds.), The biology and taxonomy of the Solanaceae, Linnean Society Symposium Series 7, pp. 385-395. The Linnean Society of London, London. [ Links ]

47. TEWKSBURY, J. 2002. Fruits, frugivores and the evolutionary arms race. New Phytol. 156: 137-139. [ Links ]

48. THURSTON, E. L. 1976. Morphology, fine structure and ontogeny of the stinging emergence of Tragia ramosa and T. saxicola (Euphorbiaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 63: 710-718. [ Links ]

49. VALENCIA, M. L. C. 1985. Anatomía del fruto de la uchuva, Physalis peruviana L. Acta Biol. Colomb. 1: 63-89. [ Links ]

50. VAN DER PIJL, L. 1982. Principles of Dispersal in Higher Plants. 3rd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York. [ Links ]

51. WAKHLOO, J. L. 1975a. Studies on growth, flowering, and production of female sterile flowers as affected by different levels of foliar potassium in Solanum sisymbriifolium Lam. II. Interaction between foliar potassium and applied gibberelic acid and 6-furfurylaminopurine. J. Exp. Bot. 26: 433-440. [ Links ]

52. WAKHLOO, J. L. 1975b. Studies on growth, flowering, and production of female sterile flowers as affected by different levels of foliar potassium in Solanum sisymbriifolium Lam. III. Interaction between foliar potassium and applied daminozide, chlormequat chloride, and chlorflurecol-methyl. J. Exp. Bot. 26: 441-450. [ Links ]

53. WEBB, M. A. 1999. Cell-Mediated crystallization of calcium oxalate in plants. Plant Cell 11: 751-761. [ Links ]

54. WEBB, M. A. & H. J. ARNOTT. 1982. A survey of calcium oxalate crystals and other mineral inclusions in seeds. Scan. Electron Microscop. 3: 1109-1131. [ Links ]

55. WEESE, T. & L. BOHS. 2007. A three-gene phylogeny of the genus Solanum (Solanaceae). Syst. Bot. 32: 445-463. [ Links ]

56. WELMAN, W. G. 2003. The genus Solanum (Solanaceae) in Southern Africa: subgenus Leptostemonum, the introduced sections Acanthophora and Torva. Bothalia 33: 1-8. [ Links ]

57. WHALEN, M. D. 1979. Taxonomy of Solanum section Androceras. Gentes Herb. 11: 359- 426. [ Links ]

58. WHALEN, M. D. 1984. Conspectus of species groups in Solanum subgenus Leptostemonum. Gentes Herb. 12: 179-282. [ Links ]

59. WHALEN, M. & D. E. COSTICH. 1986. Andromonoecy in Solanum. In: D'ARCY, W. G. (ed.), Solanaceae, Biology and Systematics, pp. 284-302. Columbia University Press, New York. [ Links ]

60. ZINDLER-FRANK, E. 1995. Calcium, calcium oxalate crystals, and leaf differentiation in the common bean Phaseolus vulgaris L. Bot. Acta 108: 144-148. [ Links ]

Recibido el 22 de octubre de 2009

Aceptado el 25 de octubre de 2010.