Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Boletín de la Sociedad Argentina de Botánica

versión On-line ISSN 1851-2372

Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. vol.52 no.2 Córdoba jun. 2017

BRIOLOGÍA

Bryophytes as a material to build birds' nests in Brazil

Leandro De Almeida Amélio1, Dimas Marchi Do Carmo2, Jéssica Soares De Lima3 and Denilson Fernandes Peralta4

1 Pós Graduação em Biodiversidade Vegetal e Meio Ambiente, Instituto de Botânica, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 - CEP 04301902 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: ednlora@gmail.com

2 Instituto de Botânica, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 - CEP 04301902 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: dimas.botanica@gmail.com

3 Instituto de Botânica, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 - CEP 04301902 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: je_up@icloud.com

4 Instituto de Botânica, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 - CEP 04301902 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. E-mail: denilsonfperalta@gmail.com

Summary

Birds' nests are elaborate constructions that are built to provide a safe and secure environment for the eggs and hatchlings of birds to develop. Twigs and leaves represent common nesting materials in birds' nests globally and with their beaks, they can carry materials, sometimes larger than the birds themselves, to construct their nests. In addition to twigs and leaves, birds also use various other materials less frequently, such as bryophytes, and in this study we examined the prevalence of bryophytes in birds' nests in Brazil. We analyzed the nest composition of 21 birds' nests from the Brazilian bryophyte collection at the Institute of Botany (SP Herbarium) and found that bryophytes were a widely used nesting material. The liverworts were dominant in terms of the species richness and the main structural components of the nests were mosses because they represent the main group of structurally bigger and constitutive bryophytes in the habitat in which the birds bred.

Key words: Birds; Brazil; Bryophytes; Nest composition.

Resumen

Briofitos como material para la construcción de los nidos de pájaros en Brasil

Los nidos de aves son construcciones complejas, hechas para proporcionar un ambiente protegido y seguro para que los huevos y las crías de pájaros se desarrollen. Las ramas y hojas representan materiales comunes de anidación, transportados por las aves en sus picos. En algunas oportunidades los materiales transportados son mayores que las propias aves. Además de las ramas y hojas, las aves también usan otros materiales (aunque menos frecuentemente), como las briofitas. Así, en el presente estudio examinamos la prevalencia de bryophytes en los nidos de las aves en Brasil. Se analizó la composición de nidos de 21 nidos de aves de la colección brasileña de bryophyte en el Instituto de Botánica (Herbario SP) y se encontró que los briófitos eran un material de anidación ampliamente utilizado. Las hepáticas eran dominantes en términos de riqueza de especies y los principales componentes estructurales de los nidos eran musgos porque representan el grupo principal de briofitas estructuralmente mayores y constitutivas en el hábitat que se criaron las aves.

Palabras clave: Brasil; Briofitos; Composición nido; Pájaros.

Introduction

Life on Planet Earth is the culmination of a plethora of biotic interactions between organisms and such interactions are ubiquitously found in water, air, soil or in the bodies of invertebrates, vertebrates, plants, fungi and microorganisms (Del Claro, 2012). The cells complexity is recorded on micro-fossils from as long as 1,200 millions of years ago, when such interactions began to be established between organisms. However, a narrow green strip can only be seen around 425 millions of years ago, with the emergence of the first terrestrial plants (Attenborough, 1992). It is estimated that about 20 millions of plant species currently live on planet earth but we only have documented about two million of them (Labandeira, 2002; Slansky & Rodriguez, 1987).

Brazil is a biodiverse tropical country, with a diverse set of ecosystems with particular vegetal and geological characteristics (Machado et al., 2007). In the case of birds, the country has an estimated 1,832 bird species (Gwynne et al., 2010) many of which are endemic (Sick, 1997), and in respect of bryophytes, Brazil has an estimated 1,525 species making it home to impressive numbers of both birds and bryophytes (Flora of Brazil, 2017).

The interactions between plants and animals are the most frequent interspecific interactions and as such, are important parts of any interactive network (Del Claro, 2012). Such interactions may be positive, negative or neutral (Arthur & Mitchell, 1989; Del Claro, 2012) and interactions which are positive for one individual and neutral for the other are characterized as commensalism (Begon et al., 2006). Meanwhile, pollination and dispersion are mutualistic interactions, whereby the plants benefit through increases in their reproductive success, while the animals receiving nutritional benefits.

The maintenance and regeneration of plant communities is often related with a diverse set of interactions with both birds and bats (Fleming & Heithaus, 1981; Levey, 1988), including no trophic interactions as observed, for example, when plants are used as a shelter or a nest (Alves et al., 2012). This type of relationship can be observed in nesting birds, and more specifically when they are building nests as many exhibit considerable cognitive abilities to build nests that are usually larger and heavier than the builders' themselves.

Birds' nests keep eggs and hatchlings in a secure environment and are often strategically placed within the birds' home range. Birds' nests are often elaborate structures (Chatellenaz & Ferraro, 2000) and the structural materials are arranged to provide a safe place in which embryos can develop and nestlings develop. The use of clay, lichens, bryophytes, and other plant materials such as leaves, roots and thin stems are frequently used as nest building materials in Brazil and around the world (Márquez, 2001, Bodrati et al., 2003).

There are only a relatively few studies about the composition of bird's nests, and more specifically about the plants chosen (Hansell 2005; Deeming & Reynolds, 2015). The materials used in the construction of the nests are usually referred as "plant", "cotton wool", "fiber", "mosses" and "lichens" (De La Penâ, 1987, Narosky & Salvador, 1998, Hansell, 2005, Deeming & Reynolds, 2015), without examination of which species of these classes were used.

Moyle's (1976) study found 65 species of mosses and classified them according the origin like aquatic (Fontinalis sp. Hygrohypnum sp., and Sphagnum sp.), terrestrial (Brachythecium sp. Hedwigia sp., Thuidium sp.) and corticicolous (Frullania sp., Platygyrium sp.). In the study of Calvelo et al. (2006), meanwhile, 22 species of bryophytes were found in birds' nests with 16 mosses and 6 liverworts.

Bryophytes were one of the first groups of plants to colonize the terrestrial environments of earth and are commonly referred to as mosses (Bryophyta), but they also include the liverworts (Marchantiophyta) and hornworts (Anthocerotophyta) (Duff et al., 2007). These plants are found in all terrestrial environments, from rainforests to areas with low moisture such as savannas, caatinga and deserts, thus being prevalent in both tropical and subtropical regions of earth (Peralta, 2005). Furthermore, they grow on various substrates such as tree trunks, rocks, soil, fresh leaves and other organic and human introduced materials as plastic, glass and others, and many birds in both temperate and tropical regions use mosses for nesting material. (Delgadillo & Cárdenas, 1990; Bordin, 2008).

Our understanding of the plants used in birds' nests is absent in Brazil, and so this study aims to identity the bryophytes present in herbarium specimens of birds' nests in the bryophyte collection of the Institute of Botany (Herbarium SP).

Materials and methods

We studied 21 birds' nests held in the herbarium of bryology "Maria Eneyda P. Kauffmann Fidaldo" (SP) of the Institute of Botany, São Paulo – Brazil (herbarium exsiccate list at Annex I). Unfortunately the specimen's labels have only "bird nest", without further information about the bird species that built the nest.

The bryophyte species identification was based on Frahm (1991), Sharp et al. (1994) Buck (1998), Gradstein et al. (2001), Gradstein & Costa (2003), Costa & Lima (2005), Costa et al. (2015), Ballejo & Bastos (2009), Yano & Peralta (2009), Yano & Peralta (2011) and Bordin & Yano (2013). Meanwhile, the classification systems follow Crandall-Stotler et al. (2009) for Marchantiophyta and Goffinet et al. (2009) for Bryophyta.

The materials used to construct the nests were analyzed and quantified at the Bryology Laboratory of Institute of Botany, using a binocular optical microscope, stereoscopic microscopes and permanent slides with Kaiser glycerined gelatin (Zander, 2003). We took this approach because some species consisted of small fragments of nesting materials and because it maintained the nests in their original structure so that they are available for further studies.

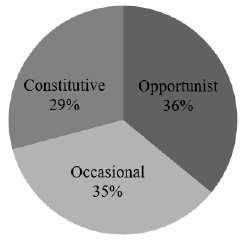

In order to classify the data, we adopt two classification systems regarding the size and constituent group were used as follows: species size (Small ≤ 2cm, Medium 2-8 cm, Big ≥ 8cm) and their group of frequency at the nest composition (Constitutive – more than 50% of the nest constitution, Opportunist – less than 10% of the nest constitution, Occasional – small fragments founded only with the stereomicroscope).

Results and Discussion

This study analyzed the nest material composition of 21 birds' nests from the Brazilian states of São Paulo (10 nests), three from Rondônia, two from Minas Gerais, two from Amazonas and one each from Bahia, Mato Grosso do Sul, Parana and Rio Grande do Sul states.

We found 57 bryophyte species in the 21 nests. The amount of liverwort species was higher in this study than Moyle (1976) for Virginia (USA) and Calvelo et al. (2006) for Patagonia (Argentina), studies performed in temperate areas, this reflects on the rich biodiversity of tropical countries and how these may have more niches than other areas.

All the nests examined had characteristics of abandoned ones, and only two of them could be distinguished as being built by hummingbirds, which meant that we were unable to relate nesting materials to bird species.

About 90% of the dried plant material was bryophytes, but we also found small twigs, roots and leaves from other plant groups in the nest materials. These materials were intertwined like the "Velcro" classification of Hansell (2000), whereby the constituents were interwoven and not easily loosened or separated which maximizes the integrity of the nest structure.

Other materials were observed intermixed within birds' nests, as previously described by Freed et al. (1987) who mentioned that hair, feathers and cotton fibers were all found in nests, and are used to create suitable thermal conditions for the optimal development of offspring both before and after hatching. Freed et al. (1987) discuss the capacity of birds to adjust the thermal qualities of their nests in response to fluctuating environmental temperatures in order to maintain optimal nest microclimates.

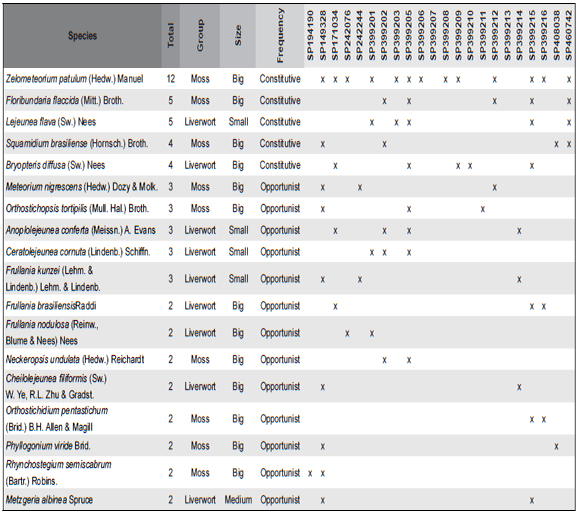

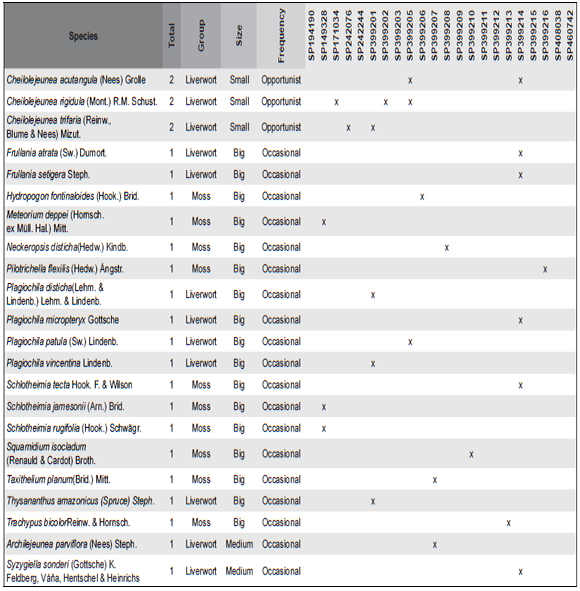

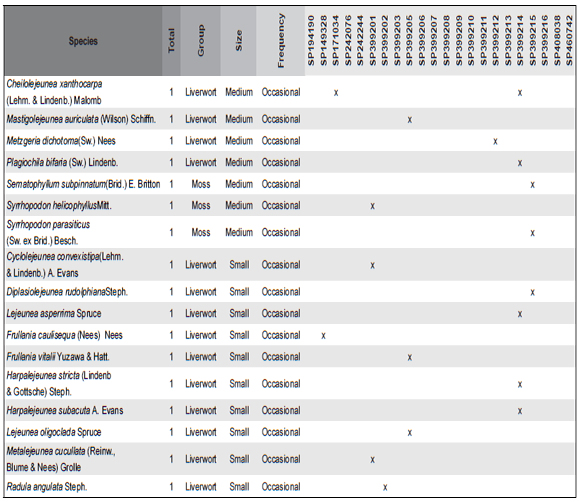

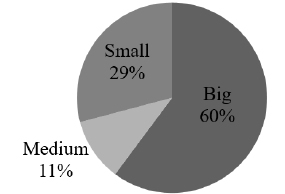

Composition of nests - Table I summarize the bryophyte species list, frequency, the size and composition group. Bryophytes made up more than 90% of the nesting material in the nests, and the size varies with 56% big species, 34% small, and 10% medium (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Checklist of bryophytes species found in the 21 Birds' nests in the herbarium of the Institute of Botany (SP) (species size (Small ≤ 2cm, Medium 2-8 cm, Big ≥ 8cm) and their frequency (Constitutive – more than 50% of the nest constitution, Opportunist – less than 10% of the nest constitution, Occasional – small fragments founded only with the stereomicroscope). The numbers were a cross reference to the samples in Annex I.

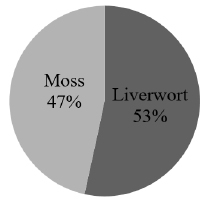

Fig. 1. Bryophyte species group composition of the 21 the birds' nests.

The commonest species were Floribundaria flaccida (Mitt.) Broth., Squamidium brasiliense (Hornsch.) Broth. and Zelometeorium patulum (Hedw.) Man. with more than four occurrences. Zelometeorium patulum was the only species with more than five occurrences, totaling 12. Meanwhile, the rare species were Anoplolejeunea conferta (Meissn.) A. Evans, Ceratolejeunea cornuta (Lindenb.) Schiffn and Frullania kunzei (Lehm. & Lindenb.) Lehm. & Lindenb. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Species size composition in the 21 the birds' nests (Small ≤ 2cm, Medium 2-8 cm, Big ≥ 8cm).

After analyzing the composition of the nests we classified the groups in terms of their frequency and the species composition. We showed that the predominance of Opportunist 36% and Occasional 35% species, because the small species are predominant in number, and the Constitutive 29% or the big ones has the small number of species (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Species frequency in the 21 the birds' nests (Constitutive – more than 50% of the nest constitution, Opportunist – less than 10% of the nest constitution, Occasional – small fragments founded only with the stereomicroscope).

More than 50% of the birds' nests composition where only five species: Zelometeorium patulum (Hedw.) Manuel, Floribundaria flaccida (Mitt.) Broth., Lejeunea flava (Sw.) Nees, Squamidium brasiliense (Hornsch.) Broth. and Bryopteris diffusa (Sw.) It is interesting to observe that among the species with the greatest composition in the nests, among them is a liverwort L. flava (Sw.) Nees, of small size, being a constitutive species. This is a generalist species, with enough occurrence in several environments, even these anthropized, what could have propitiated found there in the nests, as well as in diverse habitats.

Conclusions

The presence of bryophytes was expected in the composition of the nests, since there are records in other works of the wide occurrence for the construction of the nests, but the richness of species of liverworts in the nests was something not yet registered. Even though the liverworts were more dominant in terms of the species richness (53% liverworts x 47% moss), the main structural components of the nests were mosses because they represent the main group of structurally bigger and constitutive bryophytes.

Annex I. List of samples analyzed from the 21 birds' nest from Brazil.

Material examined: BRASIL. Amazonas. Manaus, 15-VIII-1974, Vital s.n. (SP399201); idem, Reserva Campina, 22-VI-1992, Yano & Monteiro 16911 (SP242076). Bahia. Morro do Chapéu, 3-IV-1976, Vital s.n. (SP399203). Mato Grosso do Sul. Três Lagoas, 12-IX-1992, Yano & Marcelli 17102 (SP242244). Minas Gerais, Alto Caparaó, 31-X-1994, Vital s.n. (SP399216); Itamonte, 10-VI-2015, Peralta et al. 17204 (SP460742). Paraná. Quitandinha, 23-VI-1980, Vital 9480 (SP149328). Rio Grande do Sul. Gramado, 19-VII-1980, Vital 9283 (SP149190). Rondônia, Jaru, 4-X-1986, Vital s.n. (SP399206); idem, 10-X-1986, Vital s.n. (SP399207); Ji-Paraná, 10-X-1986, Vital s.n. (SP399208). São Paulo. Bertioga, 18- V-1990, Vital s.n. (SP399211); Cananéia, 27-XI-1991, Vital s.n. (SP399213); Eldorado, 13-V-1993, Vital s.n. (SP399215); idem, 14-IV-1993, Vital s.n. (SP399214); Ibiúna, 16-I-1993, Yano s.n. (SP399212); Mogi das Cruzes, 1-XI-2008, Peralta et al. 7380 (SP408038); Peruíbe, 3-I-1987, Vital s.n. (SP399209); Registro, 10-III-1986, Vital s.n. (SP399205); idem, 13-I-1977, Vital s.n. (SP399202); Ubatuba, 9-X-1988, Vital s.n. (SP399210).

Bibliography

1. ALVES, M. A. S., M. B. VECCHI, , V. C. TOMAZ& A. J. PIRATELLI. 2012. O impacto de vertebrados terrestres sobre a comunidade vegetal: aves como exemplos de estudos. In: DEL CLARO, K. & H. M. TOREZAN-SILINGARDI (eds.) Ecologia das Interações planta-animais: uma abordagem ecológica evolutiva. pp. 89-110. Technical Books, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

2. ARTHUR, W. & P. MITCHELL. 1989. A revised scheme for the classification of population interactions. Oikos, 56: 141-143. [ Links ]

3. ATTENBOROUGH, D. F. 1992. Life on Earth: A Natural History. Collins, New York. [ Links ]

4. BALLEJOS, J. & C. J. P. BASTOS 2009. Musgos Pleurocárpicos do Parque Estadual das Sete Passagens, Miguel Calmon, Bahia, Brasil. Hoehnea 36: 479-495. [ Links ]

5. BEGON, M., C. R. TOWNSEND & J. L. HARPER. 2006. Ecology: from individuals to ecossystems. 4th ed. Blackwell Publishing, Malden. [ Links ]

6. BODRATI, A., E. MÉRIDA & L. MONTENEGRO. 2003. Nidificación del picaflor andino común (Oreotrochilus leucopleurus) en el Parque Nacional El Leoncito, Provincia de San Juan, Argentina. Nuestras Aves 45: 26–28.

7. BORDIN, J. 2008. Briófitas do centro urbano de Caxias do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Dissertação de Mestrado. Instituto de Botânica, São Paulo. [ Links ]

8. BORDIN, J & O. YANO. 2013. Fissidentaceae (Bryophyta) do Brasil. Bol. Inst. Bot. (São Paulo) 22: 1-72. [ Links ]

9. BUCK, W. R. 1998. Pleurocarpous Mosses of the West Indies. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 82: 1-401. [ Links ]

10. CALVELO, S., A. TREJO & V. OJEDA. 2006. Botanical composition and structure of hummingbird nests in different habitats from northwestern Patagonia (Argentina). J. Nat. Hist. 40: 589–603.

11. CHATELLENAZ, M. L. & L. I. FERRARO. 2000. Materiales vegetales y fúngicos en nidos de aves del noroeste argentino y Paraguay. Facena 16: 103–119.

12. COSTA, D. P. & F. M. LIMA. 2005. Moss diversity in the tropical rainforests of Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil. Revista Brasil. Bot. 28: 671-685. [ Links ]

13. COSTA, D. P., C. J. P. BASTOS & A. SCHÄFER-VERWIMP. 2015. Lejeuneaceae. In: Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro [online]. Disponible en: http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB97355 [Acceso: 20 November 2017]. [ Links ]

14. CRANDALL-STOTLER, B., R. E. STOTLER & D. G. LONG. 2009. Morphology and classification of the Marchantiophyta. pp. 1-54. In: GOFFINET, B. & A.J. SHAW, Bryophyte Biology. 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

15. DEEMING, D. C. & S. J. REYNOLDS. 2015. Nests, Eggs, and Incubation: New ideas about avian reproduction. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

16. DEL CLARO, K. 2012. Origens e importância das relações plantas animais para a ecologia e conservação. In: DEL CLARO, K. & H. M. TOREZAN-SILINGARDI (eds.) Ecologia das Interações planta-animais: uma abordagem ecológica evolutiva, pp. 35-52.: Technical Books, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

17. DELGADILLO, C. M. & A. S. CÁRDENAS. 1990. Manual de Briófitas. 2nd ed. Cuadernos del Instituto de Biologia 8. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, Mexico. [ Links ]

18. DUFF, R. J., J. C.VILLARREAL, D. C. CARGILL & K. S. RENZAGLIA. 2007. Progress and challenges toward developing a phylogeny and classification of the hornworts. Bryologist 110: 214–243.

19. FREED, L. A., S. CONANT & R. C. FLEISCHER. 1987. Evolutionary Ecology and Radiation of Hawaiian Passerine Birds. Trends Ecol. Evolut.. 2: 196-203. [ Links ]

20. FLEMING, T. H. & E. R. HEITHAUS. 1981. Frugivorous bats, seed shadows, and the structure of tropical forests. Biotropica 13: 45-53. [ Links ]

21. FLORA DO BRASIL. 2017. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro [online]. Disponible en: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/ [Acceso: 27 October 2017]. [ Links ]

22. FRAHM, J.-P. 1991. Dicranaceae: Campylopodioideae, Paraleucobryoideae. Fl. Neotrop. Monogr. 54: 1-237. [ Links ]

23. GRADSTEIN, S. R. & D. P. COSTA. 2003. The Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of Brazil. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 87:1-318. [ Links ]

24. GRADSTEIN, S. R., S. P. CHURCHILL & N. SALAZAR-ALLEN. 2001. Guide to the Bryophytes to Tropical America. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 86: 1-577. [ Links ]

25. GOFFINET, B., W. R. BUCK & A. J. SHAW. 2009. Morphology, anatomy and classification of the Bryophyta. pp. 56-138. In: GOFFINET, B. & A.J. SHAW (Second Edition). Bryophyte Biology. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

26. GWYNNE, J. A., R. S. RIDGELY, G. TUDOR & M. ARGEL. 2010. Aves do Brasil – Pantanal e Cerrado. ed. Horizonte. São Paulo

27. HANSELL, M. 2000. Bird nests and construction behavior. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

28. HANSELL, M. 2005. Animal architecture. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

29. LABANDEIRA, C. C. 2002. The history of associations between plants and animals. In: HERRERA, C.M. & O. PELLMYR (eds.) Plant Animal Interactions, an Evolutionary Approach, pp. 26-76 Blackwell, 30. Oxford. [ Links ]

31. LEVEY, D. J. 1988. Tropical wet forest treefall gaps and distributions of understory birds and plants. Ecology 69: 1076-1089. [ Links ]

32. MACHADO, G. O., M. S. MARTINS & A. L. RÓZ. 2007. Mata Atlântica. Educar, [s.l.], Licenciatura [online]. Disponible en: http://educar.sc.usp.br [Acceso: 20 October 2015]. [ Links ]

33. MÁRQUEZ, C. G. 2001. Observaciones sobre un nido de picaflor rubí (Sephanoides galeritus) en el Parque Nacional Lanín, Neuquén, Argentina. Nuestras Aves 41:12–13.

34. MOYLE, S. M. 1976. Bryophytes used in construction of Bird Nests. Bryologist 79: 95-98. [ Links ]

35. NAROSKY, T. & S. SALVADOR. 1998. Nidificación de las Aves Argentinas (Tyrannidae). Asoc. Ornit. del Plata. Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

36. DE LA PEÑA, M. R. 1987. Nidos y huevos de aves argentinas. Edic. del autor. Santa Fé [ Links ].

37. PERALTA, D. F. 2005. Musgos (Bryophyta) do Parque Estadual da Ilha Anchieta (PEIA) São Paulo, Brasil. Dissertação de mestrado, Instituto de Botânica, São Paulo. [ Links ]

38. SHARP, A. J., H. CRUM & P. M. ECKEL. 1994. The Moss Flora of Mexico. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 69: 1-1113. [ Links ]

39. SICK, H. 1997. Ornitologia brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Fronteira. [ Links ]

40. SLANSKY, F. & J. G. RODRIGUEZ. 1987. Nutritional Ecology of Insects, Mites, Spiders and Related Invertebrates. Wiley Interscience, New York. [ Links ]

41. YANO, O. & D. F. PERALTA. 2009. Flora de Grão- Mogol, Minas Gerais. Briófitas (Bryophyta e Marchantiophyta). Bol. Bot. Univ. São Paulo 27: 1-26. [ Links ]

42. YANO, O. & D. F. PERALTA. 2011. Flora da Serra do Cipó, Minas Gerais: Briófitas (Anthocerotophyta, Bryophyta e Marchantiophyta). Bol. Bot. Univ. São Paulo 29: 135-211. [ Links ]

43. ZANDER, R. H. 2003. Glycerin jelly as a substitute for Hoyer's solution [online]. Disponible en: http://www.mobot.org/plantscience/ResBot/Meth/GlycerinJelly.htm [Acceso: 5 June 2017]. [ Links ]

Recibido el 20 de febrero de 2017,

aceptado el 12 de junio de 2017.