Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Boletín de la Sociedad Argentina de Botánica

versión On-line ISSN 1851-2372

Bol. Soc. Argent. Bot. vol.53 no.2 Córdoba jun. 2018

Sistemática de Plantas Vasculares - Systematics of Vascular Plants

First Record Ofaraujia Sericifera (Apocynaceae: Asclepiadoideae) For Chile, A New Alien Climbing Species From South America

JAVIER SANTA CRUZ1 and SEBASTIÁN CORDERO2

Escuela de Agronomía, Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas y de Los Alimentos, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Calle San Francisco S/N, Quillota, Chile.

Instituto de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Campus Curauma, Avenida Universidad 330, Valparaíso, Chile. sebastian. cordero.r@mail.pucv.cl (corresponding author).

Summary: The presence of Araujia sericifera Brot. (Apocynaceae) in the vascular fora of central Chile is reported for the frst time. A morphological description and an illustration is provided, as well as a background about its habitat, ecology and phenology.

Key words: Alien species, naturalization, Valparaíso vascular fora, weeds.

Resumen: Primer registro de Araujia sericifera (Apocynaceae: Asclepiadoideae) para Chile, una nueva especie exótica trepadora de América del Sur. La presencia de Araujia sericifera Brot. (Apocynaceae) en la fora vascular de Chile central es reportada por primera vez. Se entrega una descripción morfológica y una ilustración, así como también antecedentes acerca de su hábitat, ecología y fenología.

Palabras clave: Especies exóticas, fora vascular de Valparaíso, malezas, naturalización.

Introduction

Anthropogenic activities at the global scale have strongly altered the biotic and abiotic environments with increasing speed (Van Kleunen et al., 2015), causing a weakening of the biogeographical barriers that have facilitated the dispersion of species in new regions where they can become naturalized (McNeely, 2005; Lambdon et al., 2008). Sometimes, the Introduction of plant species in new ranges derives in biological invasions, causing negative impacts on native biodiversity and ecosystems processes (Manchester & Bullock, 2000; Brooks et al., 2004). In this sense, the documentation and characterization of alien species is critical to the management of plant invasions and for the preservation of natural ecosystems (Fuentes et al., 2013). For this reason, in this study we describe for the frst time the presence of Araujia sericifera Brot. in the alien fora of Chile.

Araujia sericifera is an invasive vine belonging to the Apocynaceae family, native from northeastern Argentina, southern and southeastern Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay (Zuloaga et al., 2008; Bfig, 2015). Because of their multiple uses as a medicinal, edible, ornamental and textile plant, A. sericifera is usually cultivated worldwide (Kunkel, 1984; Gaig et al., 2005; D'Errico et al., 2014). Nevertheless, due to its ability to quickly spread, has become naturalized in Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania and South Africa (Kleinschmidt & Johnson, 1979; Joel & Liston, 1986; Hickman, 1993; Altinozlu & Donmez, 2003; Sanz et al., 2004; Henderson, 2007; Champion et al., 2010).

Araujia sericifera tends to grow in natural and disturbed habitats, where it is associated with forest and riparian vegetation (Csurhes & Edwards, 1998), as well as with species of economic interest, such as lemon and oranges trees (Sanz et al., 2004; Vladimirov et al., 2010). Its dense foliage smothers native shrubs and trees, and strangles and causes breaks tree branches, interfering with its development and preventing their natural regeneration (Weber, 2003; Sanz et al., 2004). For these reasons, it is considered as an invasive species in Australia, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Spain, South Africa, and United States (Sanz et al., 2004; D'Errico et al., 2014). Also, it has been included in the risk list by European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (D'Errico et al., 2014).

Until now, no species of the genus Araujia has been described for Chile (Marticorena & Quezada, 1985; Zuloaga et al., 2008), nevertheless, during 2016 and 2017, three populations of A. sericifera were first detected in central Chile. These populations inhabit urban settlements and crop felds, where they grow associated with other alien species. In order to increase the knowledge about alien plant species in Chile, the presence of A. sericifera in the country is reported for the frst time, and a brief morphological description and an illustration of the species are also provided.

mAterIAls And methods

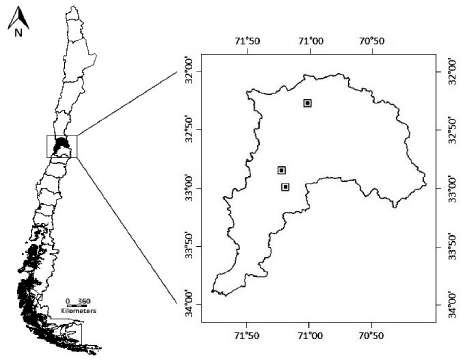

During the Austral spring and summer of the years 2016 and 2017, several foristic surveys were conducted in agricultural crops from Valparaíso region of central Chile, in which were detected populations of an unknown species in three localities: Olmué, Petorca and Quillota. Then, specimens were collected, and identification keys were used.

In order to confrm that A. sericifera is reported for the frst time for Chile, we look for other specimens of the species deposited in the SGO herbarium, as well as in checklists of the native and alien vascular Chilean fora (e.g. Marticorena & Quezada, 1985; Zuloaga et al., 2008; Fuentes et al., 2013).

results

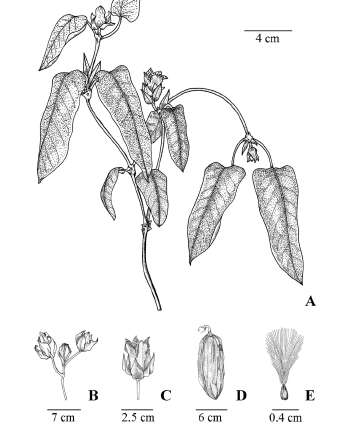

Araujia sericifera Brot. Trans. Linn. Soc. London 12: 62, t. 4-5. 1818. Type: t. 4 in Brotero, Trans. Linn. Soc. London 12: 69, 1818 (Lectotype designated by Forster & Bruyns, Taxon 41: 746. 1992). Fig. 1.

= Physianthus albens Mart. Nov. Gen. Sp. Pl. 1: 54, t. 32. 1824.

= Araujia albens G. Don. Gen. Hist. 4: 149. 1837.

= Araujia hortorum E. Fourn. Fl. Bras. 6(4): 293, t. 84. 1885. ≡ Araujia sericifera Brot. var. hortorum (E. Fourn.) Malme. Kongl. Vetensk. Acad. Handl. Ny Följd 34: 74, t. 3, f. 7. 1900.

Sub-shrub climbing or vine, up to 5 m long, evergreen, lactiferous. Stem voluble, unbranched or branched, circular in cross section and densely pubescent at the apical region. Taproot, with a main axis and smaller secondary branches. Leaves simple, opposite, petiolate with petiole of 10-20 mm long, leaf blade ovate-oblong, ovate-lanceolate or subtriangular, 40-95 x 15-60 mm, apex acuminate, base truncate or lobate, margin entire, upper surface green and glabrous, and under surface canescent and densely pubescent. Inforescences axillary of 2-5 fowers, sometimes solitary; bracts 4-10.1 x 0.9-1.9 mm; pedicels 10-16 mm long, pubescent. Calyx with 5 sepals, ovate or lanceolate, 8.5-13.3 x 5.7-8.1 mm. Corolla with tube of 11-16 x 21-28 mm, lobes 5 patent, oblong or ovate-acuminate, 7-9 x ca. 4 mm, apex obtuse, white or greenish dorsally and purple ventrally. Androecium with 5 stamens, pollinia gradually widening to the apex, forming a gynostegium inside the tube of the corolla. Follicle 85-125 x 35-55 mm, pruinosus, pendulous greenish or brown. Seeds ca. 400 per fruit, 6.3-7.8 x 2.8-3.5 mm, compressed, oval-lanceolate, rough, with pappus sericeous, 25-40 mm long, white, deciduous.

Common names: "Cruel plant", "doca", "planta cruel", "tasi", "white bladderfower".

Habitat, ecology and phenology

The presence of A. sericifera was recorded in three localities from Valparaíso region: Olmué, Petorca, and Quillota (Fig. 2). The populations from Olmué and Petorca grow in high density patches under the arboreal canopy of an avocado crop (Persea americana Mill.), and also climbing on lemon trees (Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck), orange trees (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck), olive trees (Olea europaea L.), and grape vines (Vitis vinifera L.) in agricultural crops, in association with other alien herbaceous species, such as Convolvulus arvensis L., Hirschfeldia incana (L.) Lagr.-Foss., Portulaca oleracea L., and Raphanus raphanistrum L. On the other hand, the third population from Quillota grows into a peri-urban area, in association with other alien species, such as C. arvensis, H. incana and Lactuca serriola L., and climbing on Acacia caven (Molina) Molina and on fences of the nearby houses. In all the studied locations, A. sericifera exhibits vegetative growth throughout the year, occurring its fowering between the months of December and March.

Fig. 1. Araujia sericifera. A: Floriferous branch. B: Inforescence. C: Flower. D: Fruit. E: Seed. Santa Cruz s.n. (SGO 167373). Drawing by H. Tapia Berardi.

Material examined. CHILE. Reemplazar por Region of Valparaíso: Prov. Marga-Marga, Olmué, 33°00'45''S 71°12'10'' W, 134 m, X-2016, Santa Cruz s.n. (SGO 167373); Prov. Petorca, Petorca, 32°16''45'' S 71°00'37'' W, 400 m, III-2017, Cordero s.n. (SGO 167343); Prov. Quillota, Quillota, 32°51'45'' S 71°14'09'' W, 144 m, XII-2016, Santa Cruz s.n. (SGO 167374).

dIscussIon

Araujia sericifera is capable of sustain self-replacing populations without direct human intervention by recruitment from seeds and with independent growth, for this reason, the species is suitable to be categorized as a naturalized species, according to the classifications for alien species proposed by Pysek et al. (2004). Other concepts for alien species, such as casual alien plants and transformers, are not applicable in this study for A. sericifera because its persistence is not due to repeated Introductions and no changes in the character, condition, form or nature of ecosystems over a substantial area have been observed (Pysek et al., 2004; Pysek & Richardson, 2006). On the other hand, the lack of antecedents about the distance and time of spreading of the species since its arrival in central Chile and the fact that the studied populations do not expand in large geographical areas, make it impossible to categorize it as an invasive plant (Pysek et al., 2004).

Fig. 2. Study area in Valparaíso region (central Chile), including new populations of Araujia sericifera (squares).

Since A. sericifera is widely cultivated as an ornamental species in Valparaíso region, it is possible that the species has escaped from cultivation and naturalized in surrounding areas, and eventually establishing in agricultural crops. On the other hand, an alternative explanation based on the Introduction of the species mediated by agricultural activities results less plausible because the presence of A. sericifera has been registered only in two felds of cultivation. Further, according to conversations with farmers and local people of Petorca, the presence of the species has been observed in the locality for at least 20 years, but only in recent years has it become more important as an agricultural weed.

In the agricultural plantations studied, the plants are controlled with herbicides and removed manually, as they tend to suffocate and strangle tree branches, interfering with their development and consequently reducing their production. This behavior has also been observed in other parts of the world, not only in agricultural contexts, but also in natural environments (Weber, 2003; Sanz et al., 2004). For these reasons, some preventive actions, such as avoiding the cultivation of the species for ornamental proposes in areas close to natural environments, and exhaustive inspections of agricultural felds to find new populations, could be key to control the range of expansion of the species in Chile.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hugo Tapia Berardi for the illustration and Edson Peña for allowing us to access his property to study one of the populations and provide valuable background on the species. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

bIblIogrAphy

ALTINOZLU, H. & A. DONMEZ. 2003. Araujia Brot.: a new genus (Asclepiadaceae) record for Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 27: 231-233. [ Links ]

CHAMPION, P., T. JAMES & M. DAWSON. 2010. New names for New Zealand weeds. N. Z. Plant Prot. 63: 72-77. [ Links ]

Bfig-The Brazil Flora Group. 2015. Growing knowledge: an overview of seed plant diversity in Brazil. Rodriguésia 66: 1-29. [ Links ]

BROOKS, M., C. D'ANTONIO, D. RICHARDSON, J. GRACE, J. KEELEY, J. DITOMASSO, R. HOBBS, M. PELLANT & D. PYKE. 2004. Effects of invasive alien plants on fre regimes. BioScience 54: 677-688. [ Links ]

CSURHES, S. & R. EDWARDS. 1998. Potential environmental weeds in Australia: Candidate species for preventative control. Biodiversity Group, Environment Australia, Canberra.

D'ERRICO, G., A. CRESCENZI & S. LANDI. 2014. First report of the southern root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita on the invasive weed Araujia sericifera in Italy. Plant Dis. 98: 1593-1593.

FORSTER, P. I. & P. V. BRUYNS. 1992. Clarification of synonymy for the common moth-vine Araujia sericifera (Asclepiadaceae). Taxon 41: 746-749.

FUENTES, N., A. PAUCHARD, P. SÁNCHEZ, J. ESQUIVEL & A. MARTICORENA. 2013. A new comprehensive database of alien plant species in Chile based on herbarium records. Biol. Invasions 15: 847-858.

GAIG, P., V. GÁZQUEZ, M. LOMBARDERO, E. BOTEY & P. GARCÍA-ORTEGA. 2005. Moth plant (Araujia sericifera) allergy. Allergy 60: 1092-1093.

HENDERSON, L. 2007. Invasive, naturalized and casual alien plants in southern Africa: a summary based on the Southern African Plant Invaders Atlas. Bothalia 37: 215-248.

HICKMAN, J. C. 1993. The Jepson manual: higher plants of California. University of California Press, Berkeley.

JOEL, D. & A. LISTON. 1986. New adventive weeds in Israel. Israel J. Bot. 35: 215-223.

KLEINSCHMIDT, H. & R. JOHNSON. 1997. Weeds of Queensland. Government Printer, Brisbane.

KUNKEL, G. 1984. Plants for human consumption. Koeltz Scientific Books, Koenigsten.

LAMBDON P., P. PYSEK, C. BASNOU, M. HEJDA, M. ARIANOUTSOU, F. ESSL, V. JAROSÍK, J. PERGL, M. WINTER, P. ANASTASIU, P. ANDRIOPOULOS, I. BAZOS, G. BRUNDU, L. CELESTI-GRAPOW, P. CHASSOT, P. DELIPETROU, M. JOSEFSSON, S. KARK, S. KLOTZ, Y. KOKKORIS, I. KÜHN, H. MARCHANTE, I. PERGLOVÁ, J. PINO, M. VILÀ,

A. ZIKOS et al. 2008. Alien fora of Europe: species diversity, temporal trends, geographical patterns and research needs. Preslia 80: 101-149.

MANCHESTER, S. & J. BULLOCK. 2000. The impact of non-native species on UK biodiversity and effectiveness of control. J. Appl. Ecol. 37: 845-864.

MARTICORENA, C. & M. QUEZADA. 1985. Catálogo de la fora vascular de Chile. Gayana Bot. 42: 1-157.

McNEELY, J.A. 2005. Human dimensions of invasive alien species. In: MOONEY, H., R. MACK, J. MCNEELY, L. NEVILLE, P. SCHEI & J. WAAGE (eds.), Invasive Alien Species, pp. 285-309. Island Press, Washington.

PYSEK, P. & D. RICHARDSON. 2006. The biogeography of naturalization in alien plants. J. Biogeogr. 12: 2040-2050.

PYSEK, P., D. RICHARDSON, M. REJMÁNEK, G. WEBSTER, M. WILLIAMSON & J. KIRSCHNER. 2004. Alien plants in checklists and foras: towards better communication between taxonomists and ecologists. Taxon 53: 131-143.

SANZ, M., E. DANA & E. SOBRINO. 2004. Atlas de las plantas alóctonas invasoras en España. Dirección General para la Biodiversidad, Madrid.

VAN KLEUNEN, M., W. DAWSON, F. ESSL, J. PERGL, M. WINTER, E. WEBER, H. KREFT, P. WEIGELT, J. KARTESZ, M. NISHINO, L. A. ANTONOVA, J. F. BARCELONA, F. J. CABEZAS, D. CÁRDENAS, J. CÁRDENAS-TORO, N. CASTAÑO, E. CHACÓN, C. CHATELAIN, A. L. EBEL, E. FIGUEIREDO, N. FUENTES, Q. J. GROOM, L. HENDERSON, INDERJIT, A. KUPRIYANOV, S. MASCIADRI, J. MEERMAN, O. MOROZOVA, D. MOSER, D. L. NICKRENT, A. PATZELT, P. B. PELSER, M. P. BAPTISTE, M. POOPATH, M. SCHULZE, H. SEEBENS, W.-S. SHU, J. THOMAS, M. VELAYOS, J. J. WIERINGA & P. PYSEK. 2015. Global exchange and accumulation of non-native plants. Nature 25: 100-103.

VLADIMIROV, V., F. DANE & K. TAN. 2010. New foristic records in the Balkans: 13. Phytol. Balc. 16: 143-165.

WEBER, E. 2003. Invasive Plant Species of the World: A Reference Guide to Environmental Weeds. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

ZULOAGA, F. O., O. MORRONE & M. J. BELGRANO (eds.). 2008. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares del Cono Sur (Argentina, Sur de Brasil, Chile, Paraguay y Uruguay). Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 107(2): 985-2286.

Recibido el 15 de enero de 2018, aceptado el 3 de abril de 2018. Editor: Diego G. Gutiérrez.