Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Acta Odontológica Latinoamericana

versión On-line ISSN 1852-4834

Acta odontol. latinoam. vol.26 no.3 Buenos Aires dic. 2013

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES

Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders (TDM) in patients wearing bimaxillary complete dentures, removable partial dentures and in students with natural dentition

Thaisa B. Bordin1, Ricardo A. Conci1, Maristela M. G. Pezzini1, Rolando P. Pezzini1, Márcio J. Mendonça2

1 Department of Occlusion

2 School of Dentistry, State University of West of Paraná (UNIOESTE), Cascavel, PR, Brazil;

CORRESPONDENCE Dr. Thaisa Barizan Bordin Rio Branco Street, 1900 - 85884-000 Medianeira, PR Brazil. thaisabordin@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

Temporomandibular Disorder (TMD) has attained a prominent role within the context of dental care due to its high prevalence. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMD in students at the State University of West of Parana (UNIOESTE) with natural dentition, and in patients with removable partial dentures and double complete dentures. A total of 210 randomly selected individuals of both genders were evaluated, being divided into three groups: seventy students at the UNIOESTE with natural dentition (Group 1), seventy patients with removable partial dentures (Group 2) and seventy patients with bimaxillary complete dentures (Group 3). The data were collected by a single examiner using the American Academy of Orofacial Pain questionnaire for triage, where a single affirmative response to any of the situations mentioned was enough to carry out clinical evaluation. Kolmogorov Smirnov, Mann Whitney, Chi-Square, ANOVA and Tukey's statistical tests were performed. The most prevalent signs and symptoms of TMD in Group 1 were pain or difficulty in chewing or talking, perception of recent change in bite and deviations during the course of mandibular movements. In Group 2 they were perceptions of recent changes in the bite, deflections in the mandibular movements, presence of joint sounds, pain during excursive movements and muscle tenderness. The most prevalent signs and symptoms in Group 3 were limited to mouth opening and poor stability and retention of at least one of the prostheses. Group 3 also reported having received treatment for headaches or facial pain with a high prevalence. Group 2 had the highest prevalence of signs and symptoms. Prevalence was similar in Groups 1 and 3.

Key words: Temporomandibular joint disorders; Dental prosthesis; Dentition.

Prevalência de sinais e sintomas de disfunção temporomandibular (DTM) em pacientes portadores de próteses totais duplas, próteses parciais removíveis e em estudantes com dentição natural

RESUMO

A Disfuncao Temporomandibular (DTM) tem alcancado um papel de destaque dentro do contexto odontologico devido a grande prevalencia deste problema entre a populacao. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar a prevalencia de sinais e sintomas de DTM em estudantes de Odontologia da UNIOESTE com denticao natural, em pacientes portadores de proteses parciais removiveis e proteses totais duplas. Foram avaliados 210 individuos aleatoriamente selecionados, de ambos os generos, sendo distribuidos em tres grupos: setenta estudantes de Odontologia da Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Parana (UNIOESTE) com denticao natural (Grupo 1), setenta pacientes portadores de protese parcial removivel (Grupo 2) e setenta pacientes portadores de proteses totais duplas (Grupo 3). Os dados foram avaliados por um unico examinador, sendo empregado o questionario da Academia Americana de Dor Orofacial para triagem, onde apenas uma resposta positiva das questoes formuladas foi suficiente para ser realizada a avaliacao clinica. Foi realizada a prova de Kolmogorov Smirnov, teste de Mann Whitney, do Qui-quadrado, ANOVA e Tukey para a estatistica. Os sinais e sintomas mais prevalentes de DTM encontrados no Grupo 1 foram dor ou dificuldade para mastigar ou conversar, percepcao de mudanca recente na oclusao e desvios durante a realizacao de movimentos mandibulares. No Grupo 2 foram: percepcao de mudanca recente na oclusao, deflexoes nos movimentos mandibulares, presenca de sons articulares, dor durante movimentos excursivos e sensibilidade muscular. Os sinais e sintomas mais prevalentes no Grupo 3 foram: limitacao de abertura bucal e estabilidade e retencao precarias de pelo menos uma das proteses. Tambem relataram ter realizado tratamentos para dor de cabeca ou dor na face com alta prevalencia. O Grupo com maior prevalencia de sinais e sintomas foi o Grupo 2. Houve uma prevalencia similar entre o Grupo 1 e o Grupo 3.

Palavras-chave: Disfuncao temporomandibular; Protese dentaria; Denticao.

INTRODUCTION

The Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) is a part of the stomatognathic system composed of several internal and external structures, capable of performing complex movements. Chewing, swallowing, phonation and posture depend heavily on the function, health and stability the joint to work properly1, 2.

Any change in this joint produces what we call Temporomandibular Disorder (TMD)2, which, according to the American Academy of Orofacial Pain, is defined as a group of disorders that involve the masticatory muscles, TMJ and associated structures3-8.

Although the etiology of TMD has not been fully elucidated, in general is multifactorial4, 1, 9 and may involve changes in occlusion, incorrect prosthesis, traumatic or degenerative injury of TMJ, psychological and emotional factors, missing teeth and inadequate oral habits1, 10, 11.

It is predominant in females1-3, 5, 8, 9, 11 and most authors describe it as more frequent among young adults and middle-aged individuals in the age range of 20 to 45 years3,10-13. The main symptoms include reduction of mandibular movements; decreased TMJ function; pain or muscle tenderness on palpation; pain during jaw movement; facial pain; headache and joint sounds, the latter being the most frequent2, 10, 11. TMD has attained a prominent role within the context of dentistry in recent decades4, 14. Epidemiological studies estimate that 40% to 75% of the population has at least one TMD sign, such as noise in the TMJ, and 33%, at least one symptom, facial pain or TMJ pain6.

Longitudinal studies have indicated that TMD fluctuates over time and no clear conclusion has yet been reached on its natural progression. There are various opinions on the prevalence of signs and symptoms in the dentate population, as well as the correlation between the number of teeth in occlusion and changes in TMJ15.

Some studies report that TMD appears to be almost as prevalent in patients with complete dentures as in dentate subjects. Others report that complete denture wearers have higher prevalence of symptoms than those with natural dentition8.

Al-Jabrah and Al Shumailan14 (2006) reported that patients using removable partial dentures had higher incidence of TMD signs than edentulous patients with bimaxillary complete dentures.

Pains in musculoskeletal structures of the face may have perpetuating factors that must be properly identified. This identification and the symptomatic treatment of pain also mean improvement of quality of life16.

The anamnesis and physical examination, through evaluation and palpation of muscles and TMJ, as well as evaluation of maxillomandibular relationships, are of great value in obtaining a correct diagnosis of occlusal conditions, condition of the prosthesis and level of incidence of TMD in these patients16.

Based on these considerations, the purpose of this research is to evaluate, through a triage questionnaire for orofacial pain12 and clinical examination, through part of the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD - Axis I)17 the prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms in patients with bimaxillary complete dentures, removable partial dentures and students with natural dentition.

Taking into account that these conditions can interfere with quality of life, it was proposed in this study to evaluate the prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms in UNIOESTE dental students with natural dentition, and in patients with removable partial dentures and bimaxillary complete dentures.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This research project was submitted to the Ethics Committee in Research of the Center for Health Sciences of State University of West of Parana, being approved under the Protocol 538/2010-CEP. It is in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. The sample consisted of 210 individuals, aged 19- 90 years (average 44.5 years) of both genders, divided into three groups:

Group 1 (G1) - seventy dental students from the State University of West of Parana - UNIOESTE with natural dentition;

Group 2 (G2) - seventy patients treated at the UNIOESTE Dental Clinic that wore removable partial denture (RPD);

Group 3 (G3) - seventy patients with bimaxillary complete dentures treated at Center for Dental Specialties of Cascavel - PR.

Exclusion criteria: students undergoing orthodontic treatment or less than one year after the end of orthodontic treatment, patients wearing a complete denture on one jaw and a removable partial denture on another jaw, and patients wearing just one complete denture were not included in the research.

All patients answered the questionnaire for selection of orofacial pain and temporomandibular disorders recommended by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain, consisting of ten questions directed to the most common signs and symptoms of orofacial pain and TMD. Those who provided at least one affirmative answer to the triage questionnaire underwent clinical examination, which was divided into parts, namely: identification and analysis; part of the Axis I of RDC/TMD - Research Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders; muscle palpation; and for patients with dentures, their history and clinical evaluation. Patients who provided negative answers to all the triage questions were not evaluated clinically.

The data for identification and analysis consisted of name, gender, age, presence of parafunctional habits such as centric and eccentric bruxism, onychophagy, habit of chewing gum, lip suction, nibbling cheek, tongue, tip of a pen or pencil. Part of the Axis I of RDC/TMD was used to evaluate the maximum comfortable mouth opening, mandibular deviation on opening and closing, the presence of joint noises checked with a stethoscope and pain during excursive movements (opening, closing, laterality and protrusion).

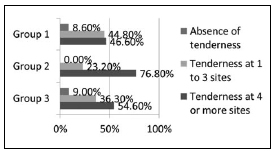

Palpation of the facial muscles such as the anterior temporal, middle and posterior, superficial and deep masseter, medial pterygoid, sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles was also performed, checking their sensitivity level, which was judged by the individual on a scale ranging from zero to three, where (0) represents no pain, (1) - mild pain, (2) - moderate pain, and (3) - severe pain. Subjects were checked for absence of sensitivity to pain, sensitivity at 1-3 sites and at 4 or more sites.

The history and clinical evaluation of the prosthesis were related to the current age of the prosthesis (in years, considering the oldest), the habit of wearing them during the day and removing them to sleep, whether patients believed that they were psychologically disturbed by the loss of their natural teeth and evaluation of stability and retention of their prostheses, being classified good or bad. If at least one of them was in a precarious condition of retention or stability, it was classified as bad.

Data were collected by a single examiner after undergoing training and calibration for four months. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with the Kolmogorov Smirnov test, the Mann-Whitney test, ANOVA (analysis of variance), Tukey and Chi- Square test, considering significant values of p<0.05. Patients received the Statement of Consent, and only patients who provided authorization were questioned and examined.

RESULTS

G1 was composed of 51 women (72.9%) and 19 men (27.1%) aged 19-27 years (average = 21.8 years). G2 included 50 women (71.4%) and 20 men (28.6%), aged 27-87 years (average = 48.5 years). G3 included 50 women (71.4%) and 20 men (28.6%) aged 41-90 years (average = 63.1 years).

All subjects answered the triage questionnaire about TMD signs and symptoms. From the natural dentition group, 12 of 70 students (6 men and 6 women) had all negative responses and were not evaluated clinically. Among the patients with RPD, 14 of 70 (7 men and 7 women), and among the patients with bimaxillary complete denture, 26 of 70 (11 men and 15 women), provided all negative answers. The remainder provided at least one affirmative response (Table 1).

Table 1: Individuals with signs and without signs and sumptoms of TMD in each group.

The analysis of responses to the anamnestic questionnaire about TMD signs and symptoms found that in G1, the highest number of affirmative responses was to Question 4 on sounds in the region of the ears (29), followed by Question 5 on the sense of tiredness in the jaws (27) and Question 7 (a) on headache (24). In G2, the highest number of affirmative responses was to Question 7 (a) (31), followed by Questions 4 and 5 (both 29). In G3, the highest number of affirmative responses was to Questions 4, 5 and 10 (18).

According to the Chi-square statistical test, there was a significant difference between G1 and the others in Question 3 (p=0.001) about TMD pain signals such as difficulty and/or pain upon chewing and speaking.

Question 8, of which the principal aim is investigating the influence of macro trauma (such as falls, car accidents, direct trauma to the maxilla or mandible or craniocervical region), differed statistically between G1 and G2, with p = 0.0024.

Question 9, which deals with patients bite perception and Question 10, about having been treated for pain in the face or headache, differed statistically between G3 and the others. The comparative analysis in relation to gender showed that there was a statistically significant difference between men in G1 and G3 (p = 0.00001) and between women in G3 and the others (p<0.003 G2 x G3, and p<0.001 in G3 x G1).

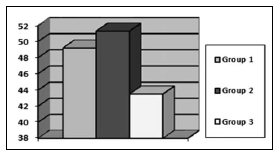

As subjects age, a statistically significant difference was found between G3 and the others (p<0.0001). Clinical examination of level of maximum comfortable mouth opening found that in G1, minimum opening was 36 mm and maximum was 61 mm, with an average of 49.2 mm, and 20.5% of the subjects having less than 40 mm opening. In Group 2, the minimum was 35 mm and the maximum was 65 mm, with an average of 51.3 mm opening, and 3.6% of the subjects having less than 40 mm. In Group 3, the minimum was 30 mm and the maximum was 54 mm, with an average of 43.5 mm, and 3.4% of the subjects having an opening smaller than 40 mm. ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) and Tukey's test were performed to verify differences among groups in relation to mouth opening, and it was found that Group 3 differed significantly from the others (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Average degree of maximum mouth opening in the three groups.

Regarding the pattern of mouth opening, in G1, 53.4% of with the subjects had deviations. In the other groups (G2 and G3), a rectilinear pattern prevailed. Mann-Whitney's statistical test was applied, showing that there was significant difference between G3 and G2.

In G2, 64.3% had joint sounds during jaw movement, which was not evident in the other groups. The statistical test showed no difference between G2 and the others, with p<0.002 compared to G1 and p=0.0001 compared to G3. Regarding pain during mandibular movements, no pain prevailed in all groups, and the group that had most pain during one or more movements was G2, with 10.7% and 17.9%, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference between G2 and the others, according to the nonparametric chi-square test (G2 X G3, p=0.001 and G2 X G3, p<0.0001). The muscle that showed the highest frequency of pain and the highest percentage of patients affected in all groups was the deep masseter. In G1, 28.4% of the subjects had sensitivity score 2 (moderate pain) and 13.8% had score 3 (severe pain). For G2, the percentages were 25.9% and 22.3%, and for G3 they were 21.6% and 22.7%, respectively. For comparative analysis, the anterior temporal muscle showed a statistically significant difference between G1 and the others and the trapezius muscle did between G2 and the others.

There was statistical difference between G2 and the others for the presence of muscle tenderness. In all groups, sensitivity in 4 or more muscles prevailed. In G2, all subjects had at least one sensitive muscle. In G1, 8.6% and in G3, 9% reported no sensitivity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Muscle tenderness in the three groups

Out of the subjects who underwent clinical evaluation, 34.5% of G1 had no parafunctional habits, 39.7% presented centric bruxism, 17.2% onychophagy and 10.3% eccentric bruxism. In G2, 25% of patients had no parafunctional habits, 51.8% presented centric bruxism, 23.2% eccentric and 17.9% onychophagy. The G3 patients, 45.5% had no parafunctional habits, 38.6% centric bruxism, 22.7% habit of sucking lip and 6.8% onychophagy. In the prostheses evaluation, 13.6% of patients had been using complete bimaxillary dentures for less than one year, 77.2% from 1 to 5 years and 9% for more than 5 years. Most of them (81.8%) wore both dentures all day and 61.4% slept with them.

In G2, 26.8% had been using the prosthesis for less than one year, 21.4% from 1 to 5 years and 51.8% for over five years. Most of them (75%) wore a prosthesis all day and 67.9% slept with it. According to the retention conditions, 29.5% of patients with complete dentures and 51.8% of patients with RPD had good prosthetic conditions. The chi-square test was performed where a significant difference was noted between G2 and G3, with p=0.008, showing that G2 prostheses had better retention and stability. In G2, 67.9% reported having been psychologically disturbed due to tooth loss and in G3, 38.6% reported the same. The most prevalent signs and symptoms of TMD in G1 were pain or difficulty for chewing or talking, perception of recent change in bite, and deviations during the course of mandibular movements.

The most prevalent signs and symptoms of TMD in G2 were perception of recent change in bite, deflections in mandibular movements, presence of joint sounds, pain during excursive movements, and muscle tenderness. In addition, there was presence of contributing, triggering and perpetuating factors such as the high prevalence of patients with parafunctional habits, with old dentures (over 5 years), with the habit of removing at least one of the prostheses during the day, removing it to sleep and even the large number of people who reported having been psychologically disturbed due to teeth loss.

The most prevalent signs and symptoms of TMD in G3 were limited mouth opening and poor stability and retention of at least one of the prostheses. Subjects in G3 also reported having received treatment for headaches or pain in the face with a high prevalence.

The highest prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms was found in patients wearing RPD, followed by patients wearing bimaxillary complete dentures. The lowest prevalence was in the group with natural dentition.

DISCUSSION

TMD is associated to multiple etiologies and presents common signs and symptoms18. The sum or exacerbation of these signs and symptoms eventually limits or even disables individuals in their physiological activities1, 19.

The higher prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms in women in this study coincides with the data in the literature1-3, 5, 8, 9, 11.

Searches in the literature that related TMD signs and symptoms with the age showed inconsistent data5. Serman et al.16 report that symptoms may vary over time and Almeida et al.10, Coronatto et al.11 and Manfredini et al.20 describe it as more frequent among young adults and middle-aged individuals, ranging from 20 to 45 years old. However, Plesh, Adams and Gansky21 disagree with these studies, because they found a correlation between increasing age and the increase in the potential for developing TMD signs and symptoms. This does not agree with the results of our study, where middle- aged individuals (average 48.3 years - G2) showed a higher incidence of signs and symptoms of dysfunction.

Several factors can be triggers, contributors or perpetuators of TMD, among them, parafunctional habits, reduction the vertical dimension of occlusion22 due to tooth loss, old dentures or the habit of not wearing the prosthesis during the day, removal of the prosthesis to sleep, lack of stability and retention of prostheses, and psychological factors. Parafunctional habits may cause serious damage to chewing structures, teeth, periodontium and TMJ, and are closely related to TMD23.

In our study, G2 presented higher prevalence of patients with parafunctional habits (75%), with statistically significant difference compared to the other groups, which is consistent with the research by Creugers et al. 24.

According to the observations of Bontempo and Zavanelli5, wearing the same prosthesis for an extended time (more than 5 years) causes the occlusal surfaces of the artificial teeth to wear out, causing alteration of the vertical dimension of occlusion, which may facilitate the development of TMD signs and symptoms. In our study, there was a high incidence of G2 patients using prostheses for more than five years, with a statistically significant difference between this group and G3, which does not agree with the study by Yannikakes, Zissis and Harrison25.

Poor adaptation of the prosthesis can cause constant muscular contractions to try to stabilize it, and can also cause pain and muscle dysfunction26. Concerning to the retention and stability of the prostheses, there was higher prevalence in G3 individuals (70.5%) wearing at least one prosthesis with poor retention and stability against 48.2% in G2, with a statistically significant difference.

There were more individuals in G2 who were not wearing the prostheses during the day than in G3. Not wearing dental prostheses causes changes in the TMJ and muscular system, whereas the rest position is changed due to loss of vertical dimension, interfering in the condylar position14.

There is a consensus among the authors that patients should be instructed to remove their dentures at bedtime to relieve the pressure on soft tissues and reduce the incidence of stomatitis10, 27 However, the literature shows that patients who do not wear their dentures while sleeping have higher muscle activity during the night28. In our study, prevalence was higher in G3 individuals who removed them (38.6%), but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (G2 and G3).

The loss of natural teeth can cause psychological problems that increase emotional stress and may contribute to the development of TMD5, 9, 11. In our study, the group with highest risk was G2 (67.9%). On clinical examination there were also signs and symptoms such as degree of maximum comfortable mouth opening, presence of deviations or deflections in the mandibular movements, presence of joint sounds, pain during excursive movements and muscle tenderness. Maximum jaw opening is one of the measures used for the evaluation of jaw function8, 14. Cattoni and Fernandes29 reported that the rates for normal maximum mouth opening range between 45 mm and 60 mm in adults, with an opening smaller than 40 mm being a warning for possible muscle and/or joint problems. In this study, maximum mouth opening was less than 40 mm in 20.5% of the patients in G3 and only 3.6% of G1 and 3.4% of G2, showing a statistically significant difference. These results are consistent with the study by Al-Shumailan and Al- Manaseer8, where the average mouth opening in patients using complete denture was lower than in the group of dentate patients. This limitation in mouth opening changes diction, mastication and consequently, deglutition2.

It should be mentioned, however, that reduced maximum mouth opening was expected in patients with complete dentures, because maintaining the stability of the inferior prosthesis during this exercise requires muscle coordination to prevent its displacement8.

In our study, the highest incidence of deviations or deflections in the mandibular movements of opening and closing the mouth found in G1 is consistent with the research by Al-Shumailan and Al- Jabrah14, where patients with RPD and bimaxillary complete dentures had a prevalence of mouth opening in a straight line. However, we found a statistically significant difference between G2 (62.5%) and G3 (52.3%).

The literature reports that joint sounds are one of the most common symptoms of TMD2, 8. In our study, we found high prevalence (64.3%) of joint sounds in patients in G2, with a statistically significant difference compared to the other groups, in agreement with the study by Al-Shumailan and Al- Jabrah14.

Regarding the complaint of pain during mandibular movements, there was a significant difference between G2 and the others. There was also higher prevalence of pain in this group (28.6%), which is in disagreement with the study by Divaris26, where edentulous patients reported more significant pain symptoms. Our study is in agreement with the studies by Al- Shumailan and Al-Jabrah14 and Al-Shumailan and Al-Manaseer8, where the most common symptom of the study groups (RPD and complete denture, and dentate and bimaxillary complete dentures, respectively) was muscle tenderness. We found high muscle tenderness in all groups, being 100% in G2, with statistical difference between this group and the others.

The most affected muscle in scores 2 and 3 was the deep masseter in all groups. Once again, our research is in accordance with the research by Al-Shumailan and Al-Jabrah14. Although the authors report that the clinical signs and symptoms of dysfunction in patients increase as the number of teeth declines, emphasizing the risk of edentulous patients with complete denture10, 28, we found a higher prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMD in G2, reiterating the claims of Wang et al. 9, who claim that it is due to the fact that the number of missing posterior teeth generally increases with age and the incidence of formation of "occlusion locked" (occlusion with teeth inclined and displaced due to the absence of adjacent teeth) decreases when the number of remaining teeth decreases.

Ribeiro et al.15 found that patients with complete dentures had TMD symptoms with a frequency similar to natural dentate. Al-Shumailan and Al- Manaseer8 found twice as many TMD signs and symptoms in dentate patients than in patients using complete dentures. All these findings disagree with the results of our study.

Serman et al.16, Cavalcante et al.30 and Divaris et al.26 report that patients with bimaxillary complete dentures had more TMD signs and symptoms than patients with natural teeth, which is consistent with our findings, as we found the same number of signs and symptoms in both groups, but fewer individuals were evaluated in G3.

The literature reviewed in this study revealed that there is still controversy regarding the prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms in different groups of individuals. There could be many reasons for this, but the most frequently suggested are differences in diagnostic criteria, clinical examination and the universe of the study population13.

1. Menezes MS, Bussadori SK, Fernandes KPS, Biasotto-Gonzalez DA. Correlation between headache and temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Fisioter Pesq. 2008; 15:183-187. [ Links ]

2. Pereira KNF, Andrade LLS, Costa MLG, Portal TF. Signs and symptoms of patients with temporomandibular dysfunction. Rev CEFAC 2005;7:221-228. [ Links ]

3. Bonjardim LR, Lopes-Filho RJ, Amado G, Albuquerque RLJr, Goncalves SR. Association between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and gender, morphological occlusion, and psychological factors in a group of university students. Indian J Dent Res 2009;20:190-194. [ Links ]

4. Bontempo KV, Zavanelli RA. Temporomandibular disorders: prevalence and treatment needs in patients with double dentures. RGO. 2011;59:87-94. [ Links ]

5. Bontempo KV, Zavanelli RA. Etiological factors related to temporomandibular disorders in patients with dentures bimaxilares: a comparative analysis. RGO 2009;57:67-75. [ Links ]

6. Carrara SV, Conti PCR, Barbosa JS. End of the first consensus on temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain. Dental Press J Orthod 2010;15:114-120. [ Links ]

7. Carvalho, LCB. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in patients with bilateral lower extremity free [monograph on the internet]. University of Brasilia. Faculty of Health Sciences, Graduate Program in Health Sciences Brasilia; 2007 [acesseced 2011 Oct 13]. URL: http://bdtd.bce.unb.br/tedesimplificado/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=2715 [ Links ]

8. Yousef R. Al-Shumailan BDS, MSc Wasfi A. Al-Manaseer BDS. Temporomandibular disorder features in complete denture patients versus patients with natural teeth; a comparative study. Pak Oral Dental J 2010;30:254-259. [ Links ]

9. Wang MQ, Xue F, He JJ, Chen JH, Chen CS, Raustia A. Missing posterior teeth and risk of temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Res 2009;88:942-945. [ Links ]

10. Almeida LHM, Lira AB, Soares MSM, Cruz JSA, Cruz RES, Lima MG. Temporomandibular disorders in the elderly. RFO UPF 2008;13:35-38. [ Links ]

11. Coronatto EAS, Zuccolotto MCC, Bataglion C, Bitondi MBM. Association between temporomandibular disorders and anxiety: epidemiologic study in edentulous patients. Int J Dent Recife 2009;8:6-10. [ Links ]

12. Manfredi APS, Da Silva AA, Vendite LL. Evaluation of the sensitivity of the screening questionnaire for orofacial pain and temporomandibular disorders recommended by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2001;67:763-768. [ Links ]

13. Ozan F, Polat S, Kara I, Kucuk D, Polat HB. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in a Turkish population. J Contemp Dent Pract 2007; 8:35-42. [ Links ]

14. Al-Jabrah OA, Al-Shumailan YR. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder signs in patients with complete versus partial dentures. Clin Oral Invest. 2006; 10:167-173. [ Links ]

15. Ribeiro RA, Mollo Junior FA, Pinelli LAP, Arioli Junior JN, Ricci WA. Symptoms of craniomandibular dysfunction in patients with dentures and dentulous natural. RGO 2003; 51:123-126. [ Links ]

16. Serman RJ, Conti PCR, Conti JV, Salvador MCG. Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction in patients with double denture. J Bras Orofac Occlusion TMJ Pain 2003; 3:141-144. [ Links ]

17. Dworkin SF, leResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specification, critique. J. Craniomandib Disord 1992;6:301-355. [ Links ]

18. Gremillion, HA. The relationship between occlusion and TMD: an evidence-based discussion. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2006;6:43-47. [ Links ]

19. Locker D, Quinonez C. To what extent do oral disorders compromise the quality of life? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011;39:3-11. [ Links ]

20. Manfredini D, Piccotti F, Ferronato G,Guarda-Nardini L. Age peaks of different RDC/TMD diagnoses in a patient population. J Dent 2010;38:392-399. [ Links ]

21. Plesh O, Adams SH, Gansky SA. Racial/Ethnic and gender prevalences in reported common pains in a national sample. J Orofac Pain 2011;25:25-31. [ Links ]

22. Compagnoni, MA Determinacao da dimensao vertical em pacientes desdentados totais. In: Lubiana NF, Bonfante G, Thadeu Filho M Pro-Odonto Protese - Programa de atualizacao em protese odontologica. Ciclo 1. Modulo 1, Organizadores. Porto Alegre: Artmed/Panamericana, 2009; 1:65-105. [ Links ]

23. Melo GM, Barbosa JFS. Parafuncoes e DTMs: Influencia dos habitos parafuncionais na etiologia dos disturbios temporomandibulares. Pos-perspect Oral Sci 2009; 1:12-17. [ Links ]

24. Creugers NHJ, Witter DJ, Spijker AV, Gerritsen AE, Kreulen CM. Occlusion and temporomandibular function among subjects with mandibular distal extension removable partial dentures. Int J Dent 2010; 2010:807850. DOI 10.1155/2010/807850. [ Links ]

25. Yannikakis S, Zissis A, Harrison A. The prevalence of temporomandibular disorders among two different denture-wearing populations. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 2009;17:35-40. [ Links ]

26. Divaris K, Ntounis A, Marinis A, Polyzois G, Polychronopoulou A. Loss of natural dentition: multi-level effects among a geriatric population. Gerodontology 2012; 29:e192-199. [ Links ]

27. Compagnoni MA, Souza RF, Marra J, Pero AC, Barbosa DB. Relationship between Candida and nocturnal denture wear: quantitative study. J Oral Rehabil 2007;34:600-605. [ Links ]

28. Johansson A, Unell L, Carlsson GE, Soderfeldt B, Halling A. Gender difference in symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders in a population of 50-year-old subjects. J Orofac Pain 2003;17:29-35. [ Links ]

29. Cattoni DM, Fernandes FDM.. Distancia interincisiva maxima em criancas na dentadura mista R Dental Press Ortodon Ortop Facial 2005;10:117-121. [ Links ]

30. Cavalcante BL, Stechman JN, Carrilho E, Milani PAP..Dor orofacial em pacientes desdentados totais: levantamento epidemiologico. PCL - Rev Bras Prot Clin Lab 2004;6: 593-597. [ Links ]