Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Acta Odontológica Latinoamericana

versión On-line ISSN 1852-4834

Acta odontol. latinoam. vol.31 no.1 Buenos Aires abr. 2018

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Risk factors for early childhood caries experience expressed by ICDAS criteria in Anapoima, Colombia. A cross-sectional study

Factores de riesgo de experiencia de caries temprana expresada con criterios ICDAS en niños de Anapoima, Colombia. Estudio de corte transversal

Stefania Martignon1,2, Margarita Usuga-Vacca1, Fabián Cortés3, Andrea Cortes1, Luis Fernando Gamboa1, Sofía Jacome-Lievano1, Jaime Alberto Ruiz-Carrizosa1, María Clara González-Carrera4, Luis Fernando Restrepo-Perez4, Nicolás Ramos5

1 Universidad El Bosque, Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones, Unidad de Investigación en Caries, Bogotá, Colombia.

2 King's College London Dental Institute, Dental Innovation and Translation Centre, London, United Kingdom.

3 Universidad El Bosque, Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones, Bogotá, Colombia.

4 Universidad El Bosque, Facultad de Odontología, Bogotá, Colombia.

5 Universidad El Bosque Programa de Pediatría, Bogotá, Colombia,

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to assess whether caries risk, nutritional status, access to dental care and socio-behavioral factors are associated to two caries experience outcome variables using the Epidemiologic International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDASepi), which includes initial enamel caries lesions: 1- The presence of ICDAS-epi caries experience (dmf-ICDASepi ≥ 1), and 2- Having an ICDAS-epi caries experience (dmft-ICDASepi) higher than national figures for the same age. The sample included 316 eight- to 71-month-old children from the municipality of Anapoima, Colombia. Assessments included: prevalence and mean of caries experience using the ICDASepi system without compressed air-drying of teeth surfaces (dmf-ICDASepi), caries risk and nutritional status. Caregivers completed an elevenitem questionnaire assessing oral health-related social determinants, practices and quality of life (OHRQoL), and children's access to dental care. Data were analysed using the Wilcoxon-rank-sum test, the test, the Fisher-exact test, and bivariate-linear and non-conditioned logistic-multivariate regression models. Prevalence and mean number of teeth with dmft-ICDASepi were 65.2% and 3.5±4.13, respectively. Nutritional status outside the normal status, lower educational level of caregivers and age were significantly associated with dmf-ICDASepi≥ 1. OHRQoL, access barriers to miss and to attend dental care, operative-treatment or emergency being the reason to attend dental care, high caries risk, and age were significantly associated with a higher-than-national dmft-ICDASepi. The significant associations found between early childhood caries experience and other variables represent oral-health inequalities in early childhood in Anapoima, Colombia.

Key words: Dental caries; dental care; Nutritional status; Health services accessibility; Quality of life.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar en la primera infancia la asociación entre el riesgo de caries, el estado nutricional, el acceso a la consulta odontológica y los factores socio-comportamentales y dos variables de desenlace de experiencia de caries usando el Sistema epidemiológico Internacional de Detección y Valoración de Caries (ICDASepi), que incluye lesiones de caries en el esmalte: 1-La presencia de experiencia de caries ICDAS-epi (ceod-ICDASepi ≥ 1) y, 2- Tener una experiencia de caries ICDASepi (ceod-ICDASepi) mayor que los datos nacionales correspondientes para la misma edad. La muestra fue de 316 niños del municipio de Anapoima, Colombia, de 8 a 71 meses de edad. Las valoraciones incluyeron: prevalencia y promedio de experiencia de caries usando el sistema ICDASepi sin secado de las superficies de los dientes con aire comprimido (dmf-ICDASepi); riesgo de caries y estado nutricional. Los cuidadores respondieron un cuestionario de once ítems que valoraba en relación con salud oral, determinantes sociales, prácticas y calidad de vida y, el acceso de los niños a la consulta odontológica. Los datos fueron analizados con la prueba de suma de rangos de Wilcoxon, la prueba de χ2, la prueba exacta de Fisher y, modelos de regresión logística multivariada tipos bivariantelineal y no condicionada. La prevalencia de experiencia de caries (ceod-ICDASepi) fue de 65.18% y el promedio de dientes con ceod-ICDASepi de 3.5 ± 4.13. El estado nutricional por fuera de rangos de normalidad, el bajo nivel educativo de los cuidadores y la edad se asociaron significativamente con ceo-ICDASepi ≥ 1. Se encontró asociación estadísticamente significativa entre tener un ceod-ICDASepi mayor que el promedio nacional y, calidad de vida relacionada con salud oral, barreras de acceso para perder y asistir a consulta odontológica, tratamiento operatorio o urgencia como motivo de consulta odontológica, alto riesgo de caries y edad. Las asociaciones estadísticamente significativas encontradas en este estudio entre la experiencia de caries de infancia temprana y demás variables representan inequidades en salud oral en la primera infancia en Anapoima, Colombia.

Palabras clave: Caries dental; Atención odontológica; Estado nutricional; Accesibilidad a los servicios de salud; Calidad de vida.

INTRODUCTION

Over half the children in Latin America are affected by the most severe form of caries (cavitation/dentinal caries lesions)1. Studies have shown significant association between caries in children and caries experience, oral health-related quality of life (OHQoL), socio-economic determinants, access to dental care, oral health care practices, diet and nutritional status2-6.

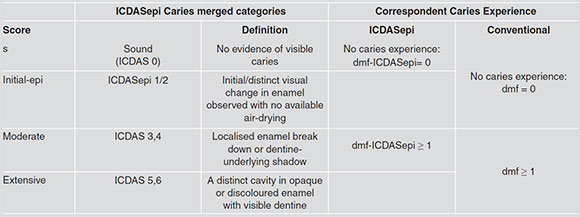

In Colombia, the recent National Oral Health Study (NOHS) reported conventional caries experience (with cavitation/dentinal caries lesions) (WHO basic reporting codes) as well as ICDAS (International Caries Detection and Assessment System) caries experience with the Epidemiologic modification (no compressed air available) (ICDASepi). In addition to the conventional caries experience, it reported initial caries lesions on enamel with no cavitation (ICDAS Initial: codes 1-2)7 (Table 1). Prevalence of conventional caries experience (dmft) in 5-year-old children was 62% with mean dmft of 2.8 (dt: 1.9), increasing to 89% and 6.8, respectively, when initial caries lesions were included (dmft-ICDASepi)8. The same study reported inequalities and barriers to access to healthcare.

With regard to the nutritional status of Colombian children, national data show that young children (up to the age of 6 years) present2.5% acute malnutrition and 12% chronic malnutrition, with rates higher than 20% for subgroups in rural areas9.

In its effort to achieve better general and oral healthcare, for more than three decades the Colombian General Social Healthcare Security System (abbreviated SGSSS in Spanish) has developed better general/oral healthcare legislation and programs: Statutory Law 1751 of 201510, which guarantees the fundamental right to health; Law 1438 of 201111, which guarantees healthcare; Law 100 of 199312, which extends coverage to the entire population; the positioning of oral health as a third priority in public healthcare13; the 2010 Primary Healthcare14, and reinforcement of healthcare through the programmes "De 0 a Siempre" (From 0 to Always) and "Soy generación sonriente" ("I belong to a smiling generation") implemented by the Ministry of Health and Social Protection15.

A four-university team recently launched the Colombian Chapter of the Alliance for a Cavity-Free Future (2011)16, which is a worldwide initiative seeking caries-free cohorts. Thus, El Bosque University agreed with Anapoima-Cundinamarca's municipal government and the community to jointly construct an early-childhood oral/general health model, which is part of an ongoing implementation study.

Taking into account the importance of better general and local understanding of the associations between risk factors and caries experience, the aim of this study was to assess, in young children, how caries risk, nutritional status, access to dental care and socio-behavioral factors are associated to two outcome variables: (1) ICDASepi caries experience ≥ 1, and (2) ICDASepi caries experience higher than national figures for the same age.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was across-sectional study conducted on children 8 to 71 months old from Anapoima, Cundinamarca, Colombia, with IRB (UEB-2011-149), following the STROBE Guidelines. Anapoima Municipality is located in Cundinamarca State in the western Andes range, approximately 87 Km southwest of Bogotá (Colombia's capital city), at 650-950 masl and temperatures 22-28 °C. Population is 13,659 (urban area 5,709)17. Sample size was based on a related prospective study which reported that there were 1,200 children under 6 years of age in Anapoima (type-I error: 0.05 probability, 0% expected population proportion, 5% population-proportion distance), resulting in a sample size of 272 children. A 20% over-sample was added to prevent for drop-outs in the future program, resulting in a total sample of 326 children. The municipal government runs a program to improve nutrition, through which once a month, families with children are invited to receive food supplements. Participation rate is higher than 80%. In connection with this program, radio announcements were broadcast, inviting children to participate in an oral and nutritional examination. The children were examined at the healthcare centre in order of attendance until the sample size was completed. Informed consent was obtained from their caregivers. Subjects were thus selected from a random sample representative of the study population.

Exclusion criteria were: children whose parents did not agree to participate, children whose behaviour prevented examination, and children whose teeth had not yet erupted.

All participants received an oral-hygiene toolkit and referral to a dentist if needed.

Data collection

Assessments were conducted from November to December 2012. Clinical assessments included caries, caries risk and nutritional status. Five dentists trained and calibrated in the ICDAS caries assessment system (inter/intra-examiner reproducibility Kappa values > 0.7) assessed caries with the ICDASepi system under epidemiological field conditions, at the Anapoima health centre, after assisted toothbrushing, with portable units, headlamp, mirror, drying cotton (no compressed air available) and WHO ball-ended probes. Filled (f) and missing (m) surfaces were also included in the examination. The caries component ("d") for the conventional caries experience was the same as the one used in the 2015 NOHS8, namely Moderate and Extensive (dentinal) lesions (Conventional caries experience: dmfs/t). The ICDASepicaries experience also included Initial epicaries lesions (dmfs/t-ICDASepi)7 (Table 1).

Table 1: Clinical ICDASepi Caries Categories, and ICDASepi and Conventional Caries Experience.

Individual caries risk was assessed with the Cariogram® software18,setting country risk as high, group risk as standard, and assessing eight of ten factors (excluding salivary buffer capacity and microbiological tests) clinically and by interviewing caregivers, and using national data for mean number of teeth with caries experience for each child's age8. Each individual's caries risk was classified as low (very low - low), intermediate, or high (high-very high).

Nutritional status was assessed at the same session, in line with WHO guidelines as adopted for Colombia19. Height and weight were measured by 4 trained physicians with achild meter and electronic table scale in children < 2 years of age and with a height rod and upright scale in children > 2 years of age. Nutritional status was calculated by means of the height to weight indicator in children under 5 years old and by means of the body mass index (BMI) age indicatorin 5-year-olds. Children's nutritional status was classified as undernutrition, underweight, normal, overweight or obese.

Access to oral healthcare and socio-behavioural aspects

An eleven-question survey, modified from nationally validated tools, was applied in the same session to parents/caregivers with regardto the children's oral health-related access to dental care (3 questions); social determinants (2 questions)8; practices (3 questions)20, andquality of life (3 questions)21.

Statistical analysis

For the general description of the variables, central tendency measures (means) and dispersion (standard deviation) were used in quantitative variables, with previous confirmation of normality distribution by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test. In case of non-normal distribution, variables were described using medians and interquartile ranks. For the comparison between subjects with and without ICDAS-epi caries experience, as well as the group of individuals with a higher-than-national vs. the lower/equal mean for ICDAS-epi caries experience, the Z-test was used for mean differences in continuous variables with normal distribution or non-parametric statistics (Wilcoxon rank sum test). The Z-test for difference in proportions was used for dichotomous qualitative variables, and for multiple qualitative variables when the expected values in each cell were >5,x2; otherwise, the Fisher exact test was used.

The association between socio-behavioural aspects (access to oral healthcare, social determinants, practices, and quality of life), and the study outcomes (caries experience and higher-than-national-mean caries experience) was initially estimated in a bivariate way using OR (odds ratio), followed by a x2 test. In order to adjust such association according to the presence of confounding and interaction variables, adjusted ORs were obtained by means of a non-conditioned logistic regression multivariate model. For the selection of the regression variables, the stepwise technique was used, with an entry probability of 0.1 and an exit probability of 0.25, from a complete model with the variables described in the literature as effect modifiers, as those statistically different between groups and the possible interactions that could occur.

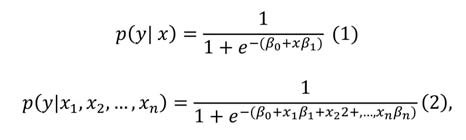

The crude and adjusted odds ratio was estimated using the logistic regression model (1) and (2), respectively:

wherep(y|x) andp(y|x1, x2,. . . ,xj are the probability of presenting the outcome given the explanatory variables x or x1, x2,...,Xn for crude and adjusted models, respectively, and the OR are eΒ1 for both models.

The reliability of each of these models was evaluated using the Deviance and the Hosmer-Lemeshov goodness to fit test.

In order to correct the type I error by multiple comparisons test, a corrected type I error a was calculated using the Bonferroni correction, where α = α|κ, being α = 0.05 the type I error rate and the number of null hypotheses; all statistical tests whose were p ≤ α considered to be statistically significant.

The rest of the statistical tests were considered significant at a p-value<0.05. The statistical analysis was conducted using STATA software (Version 12 SE; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

In total, 316 eight- to 71-month-old children were included in the assessment of both study outcomes: presence of dmfs-ICDAS-epi ≥ 1, and dmft-ICDASepi mean higher than the national mean for same age group. More than half were girls (56.01%) and of urban origin (55.38%). Caries risk in most children were classified as high (61.07%), followed by low (26.88%) and intermediate (12.02%). Over one third of children were classified outside a normal nutritional status (34.17%), with 24.05% classified as presenting overweight or obesity.

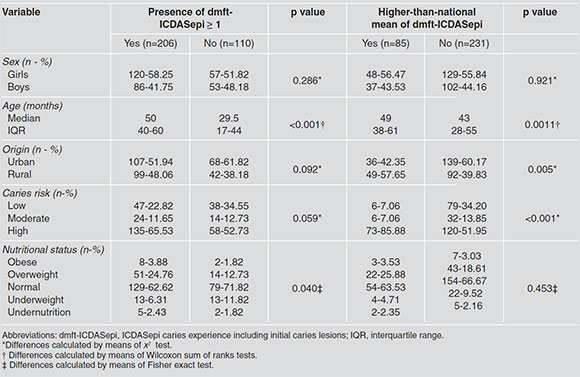

The prevalence of Conventional caries experience (dmf) was of 37.41%, increasing to 65.18% with the dmf-ICDASepi. Statistically significant differences were found between children with and without any level of caries experience (enamel or dentinal) and the variables of age and nutritional status (Table 2).

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics, caries risk and nutritional status of subjects according to the presence of dmft-ICDASepi ≥ 1 and of a higher-than-national mean of teeth with dmft-ICDASepi.

The mean Conventional caries experience was 1.4±2.5 (dmft) and 2.5±5.3 (dmfs; ds: 2.0±4.5), increasing to 3.5±4.13 (dmft-ICDASepi) and 7.5± 10.21 (dmfs-ICDASepi; ds-ICDASepi: 4.5±6.6). For the outcome higher-than-national ICDASepicaries experience (dmft-ICDASepi) for same age, Table 2 shows that statistically significant differences were found between children with anequal/lower and higher-than-national mean of dmft-ICDASepi and the variables origin, caries risk and age.

Table 3 shows the analysis of factors associated to presence/absence of ICDASepi caries experience, both with the crude model and with the model adjusted by age, caries risk, and nutritional status. A statistically significant association was found only with the adjusted model regarding access to oral healthcare for the parents' maximum educational level, with children with presence of caries experience reporting 1.9 times more parents' maximum educational level as primary school vs. secondary school (p=0.043).

Table 3: Factors associated with the presence of ICDASepi caries experience (dmft-ICDASepi≥ 1).

Table 4 shows the analysis of factors associated to having a higher-than-national mean dmft-ICDASepi, both with the crude model and with the model adjusted by patients' OHRQoL, origin, caries risk, and age. In relation to OHRQoL, statistically significant associations were found for all three risk factors; only with the crude model for the child having presented tooth pain (sometimes/frequently during the last three months vs. never) during the last three months (OR: 2.89; p=0.001); with both the crude (OR: 24.5; p=0.003) and the adjusted (OR: 12.02; p=0.022) models regarding the child having stopped activities (sometimes/frequently vs. never) during the last 3 months due to tooth pain; and with both the crude (OR: 4.8; p=0.002) and the adjusted (OR: 3.85; p=0.013) models regarding the family members having had their sleep interrupted (sometimes/frequently vs. never) during the last 3 months due to child's tooth pain. With the adjusted model, the access to oral healthcare variable regarding access barriers for taking the child to dental care showed statistically significant association with children with a higher-than-national dmft-ICDASepi(OR: 2.98; p=0.043). With regard to children not receiving dental care due to access barriers, strong statistically significant associations were found with both the crude (OR: 6.55; p<0.001) and the adjusted model(OR: 4.49; p=0.011). A statistically significant association was found only with the crude model regarding oral-health practices for operative treatment (OR: 6.8; p<0.01) and emergency (OR: 4.19;p<0.01) as the reason for child's last appointment vs. check-up or prevention.

Table 4: Factors associated with the presence of higher-than-national teeth mean ICDASepi caries experience (dmft-ICDASepi).

DISCUSSION

This study explored whether early childhood caries is associated to caries risk, nutritional status, access to care and socio-behavioural factors in young Colombian children in the municipality of Anapoima, Cundinamarca. Two caries experience outcome variables were established for exploring the associations: one within a more general scenario, where children were split into with/without caries experience, and the other within a more national scenario intended to gain further insight into the situation of more vulnerable children and their surrounding factors22, where children were split into with/withouthigher-than-national mean dmft-ICDASepifor same age group. This study found significant associations between early childhood ICDASepi caries experience and nutritional status, OHRQoL, dental care access barriers, caregivers' educational level, caries risk, and age.

The ICDAS caries system was used in this study, as it is compatible with the WHO conventional caries assessment and at the same time broadens the information about disease in a population, enabling better understanding of related risk factors and supporting public health measures722-24. Colombia, among other countries, used the ICDAS caries system in its recent National Oral Health Study8. This supports the use of the ICDAS caries system in the current study to gain further insight into possible associations of risk factors with caries, including early manifestations of caries, i. e. , non-cavitated enamel caries lesions (Initial).

In this population, the prevalence of conventional caries experience was higher than 50% (4-yr. olds: 55%; 5-yr. olds: 53%) but lower than the national values reported in the recent NOHS for 5-year olds (62%)8, and values reported recently in Bogotá in 4- (59%) and 6-yr. olds (66%)23. When initial caries lesions were included, the prevalence of ICDAS-epi caries experience in the total population was slightly lower (65.18%) than equivalent modified ICDAS caries experience for the country (NOHS) for same ages (67.05%)8.

Even though a convenience sample was selected in this study, the high participation rate in the local governmental nutrition programme and call to participate in a free oral and nutritional health examination provided subjects from both affluent and less affluent areas. It is however possible, that children from less needy families were less likely to participate in the programme.

The significant association between ICDASepi caries experience ≥ 1 and malnutrition is in agreement with Gaur and Nayak5. Overweight and obesity were more frequent in children with ICDASepi caries experience (29%) than were low-weight risk and malnutrition (9%), representing a public health alert. Recent evidence shows association between high free-sugar daily intake and caries25.

Aspects of oral health-related quality of life were strongly associated to both outcomes. Sheiham3 also found an association between caries and decreased quality of life in preschool children. The lack of association in this study between the two outcome variables and social determinants might be due to the facts that the study population is smaller and more homogeneous than in other national municipalities and that formal employment is higher, possibly with higher income levels. Social determinants have been shown to be important in the NOHS8, and are part of the dental caries 'Global oral health inequalities' task group agenda worldwide26. The significant association between caries experience and access to dental care as well as between caries experience and rural/urban origin (borderline) might reflect social inequalities, in agreement with the NOHS8. Insurance limitations and a shortage of dentists have been related to low income 26. The latter might explain the local situation and reinforces the significant association found with the crude model between higher-than-national mean of ICDASepi experience and visiting the dentist for operative treatment/emergency.

The significant associations found between both outcome variables and age, while logical with regard to natural caries history, also refer to a relevant age increase in caries experience in this study. This may reflect problems with dental care at early ages and may be partially explained by Colombia's 2000 legislation, which established that a child's first dental visit should take place at 2 years of age, including only operative treatment of cavitated caries lesions. Since 2011, it has included bi-annual fluoride varnish applications starting at the age of one year, among other oral health promotion and prevention activities8. This aspect is also supported in this study by the association between a higher-than-national mean number of teeth with ICDASepi caries experience and caries risk. It should however be noted that the Cariogram includes caries experience as one of its factors, with an implicit association effect. When analysing other relevant risk factors in this population using the Cariogram, most children presented high and frequent daily intake of carbohydrates (66.5%), which is common in Colombian diet, and more than half reported not using fluoride toothpaste (56%) even though there is strong evidence that fluoride toothpaste prevents and controls caries as from the eruption of the first teeth27.

This study and the NOHS8show that action is needed to improve oral health in infants and young children. In Anapoima, these actions, among others framed in the current paradigm of caries, are already being conducted with an emphasis on early childhood, together with government, health, education, families and community bodies, within the Colombian Chapter of the Alliance for a Cavity Free Future16.

This study found significant associations between early childhood caries experience and nutritional status, OHRQoL, dental care access barriers, caregivers' educational level, caries risk, and age, both in terms of any ICDASepi caries experience and of having a higher-than-national mean figures of ICDASepi caries experience, representing oral health inequalities in early childhood in Anapoima, Colombia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the partial funding of the study by the Colombian Chapter of the Alliance for a Cavity Free Future - Colgate Palmolive; the municipality of Anapoima - Cundinamarca; María Beatriz Ferro from Colgate Palmolive; UNICA, the dentists and Paediatrics Specialization residents from Universidad El Bosque. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CORRESPONDENCE

Dra. Stefania Martignon

UNICA - Unidad de Investigación en Caries, Vicerrectoría de Investigaciones, Universidad El Bosque

Av. Cra 9 No. 131 A - 02 Edificio de Laboratorios, 2o Piso Bogotá, 110121 - Colombia

martignonstefania@unbosque.edu.co

1. Gimenez T, Bispo BA, Souza DP, ViganóME, Wanderley MT, Mendes FM, Bonecker M, Braga MM. Does the Decline in Caries Prevalence of Latin American and Caribbean Children Continue in the New Century? Evidence from Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0164903. doi: 10.1371/journal. pone. 0164903 [ Links ]

2. Fontana M, Santiago E, Eckert GJ, Ferreira-Zandona AG. Risk Factors of Caries Progression in a Hispanic School-aged Population. J Dent Res 2011;90:1189-1196. [ Links ]

3. Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight, growth and quality of life in Pre-school children. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 625-626. [ Links ]

4. Albino J, Tiwari T. Preventing Childhood Caries: A Review of Recent Behavioral Research. J Dent Res 2016; 95:35-42. [ Links ]

5. Gaur S, Nayak R. Underweight in low socioeconomic status preschool children with severe early childhood caries. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2011; 29:305-309. [ Links ]

6. Gao XL, Hsu CY, Xu Y, Hwarng HB, Loh T, Koh D. Building caries risk assessment models for children. J Dent Res 2010; 89:637-643. [ Links ]

7. ICDAS, International Caries Detection and Assessment System URL:www.icdas.org [ Links ]

8. Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social - República de Colombia. URL: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/PP/ENSAB-IV-Situacion-Bucal-Actual.pdf [ Links ]

9. Neufeld L, Rubio M, Pinzón L, and Tolentino L. Nutrición en Colombia: estrategia de país 2011-2014. Santiago de Chile: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. 2010. URL: http://www.piaschile.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Nutricion-en-Colombia-Estrategia-de-pa%C3%ADs-2011-20141.pdf [ Links ]

10. Ley Estatutaria 1751/2015 de 16 de Febrero. Bogotá. URL: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Normatividad_Nuevo/Ley%201751%20de%202015.pdf [ Links ]

11. Ley 1438/2011. Bogotá, Congreso de Colombia. URL: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=41355 [ Links ]

12. Ley 100/1993. Bogotá, Congreso de Colombia. URL: http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=41355 [ Links ]

13. Ministerio de Protección social, Bogotá. Decreto 3039/2007 . URL: http://www.ins.gov.co/normatividad/Normatividad/DECRET0%203039_2007%20Plan%20Nacional%20SP% 202007-2010.pdf [ Links ]

14. Estrategia de Atención Integral a la Primera Infancia. República de Colombia: Gobierno de Colombia. URL: http://www.deceroasiempre.gov.co/QuienesSomos/Documents/Fundamientos-politicos-tecnicos-gestion-de-cero-a-siempre.pdf [ Links ]

15. Lineamientos Estrategia incremental de cuidado bucal y protección específica en salud bucal, para primera infancia, infancia y adolescencia "Soy generación sonriente". República de Colombia: Ministerio de Salud y Protección social. URL: http://www.deceroasiempre.gov.co/QuienesSomos/Documents/Fundamientos-politicos-tecnicos-gestion-de-cero-a-siempre.pdf [ Links ]

16. The Alliance for a Cavity-Free Future. Boston: URL:www.allianceforacavityfreefuture.org [ Links ]

17. Anapoima. Sitio oficial de Anapoima en Cundinamarca, Colombia. URL: https://archive.is/20121127162132/ http://www.anaima-cundinamarca.gov.co/nuestraalcaldia.shtml?apc=a1I1-&m=q

18. Bratthall D, Hansel-Petersson G Stjernsward J. Cariogram Internet Version 2.01. Malmo, Sweden. URL: https://www.mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Odontologiskafakulteten/Avdelning-och-kansli/Cariologi/Cariogram/ [ Links ]

19. WHO, World Health Organization]. Geneva. URL: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/Technicalreport.pdf

20. Martignon S, Bautista-Mendoza G, González-Carrera M, Lafaurie-Villamil G, Morales V, Santamaría R. Instruments for evaluating oral health knowledge, attitudes and practice for parents/caregivers of small children. Rev Salud Pública (Bogotá) 2008;10:308-314. [ Links ]

21. Tellez M, Martignon S, Lara JS, Zuluaga J, Barrero L, Builes L, Cordoba D, Gomez J. Correlación de un instrumento de calidad de vida relacionado con salud oral entre niños de 8 a 10 años y sus acudientes en Bogotá. CES Odontol. 2010; 23:9-15. http://revistas.ces.edu.co/index.php/odontologia/article/view/662 [ Links ]

22. Pitts NB, Ekstrand KR. International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) and its International Caries Classification and Management System (ICCMS) - methods for staging of the caries process and enabling dentists to manage caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013; 41:e41-52. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12025 [ Links ]

23. Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, Ekstrand K, Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Tagami J, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17030. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.30 [ Links ]

24. Cortes A, Ekstrand KR, Gamboa LF, González L, Martignon S. Caries status in young Colombian children expressed by the ICCMST visual/radiographic combined caries staging system. Acta Odontol Scand 2017; 75:12-20. [ Links ]

25. Moynihan PJ, and Kelly SA. Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: systematic review to inform WHO Guidelines. J Dent Res 2014; 93:8-18. [ Links ]

26. Pitts N, Amaechi B, Niederman R, Acevedo AM, Vianna R, Ganss C, Ismail A, et al. Global oral health inequalities: dental caries task group-research agenda. Adv Dent Res 2011; 23:211-220. [ Links ]

27. Marinho VC, Worthington HV, Walsh T, Clarkson JE. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 7:CD002279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002279.pub2 [ Links ]