INTRODUCTION

Courses at health science universities focus on generating human resources that are technically qualified and able to use strategies aimed at improving individual and community health1,2. The educational process promotes meaningful learning from the standpoint of social demands and personal development, understanding meaningful learning to mean a personal action that is achieved due to the flexibility of neural networks3,4.

In Argentina, there are 18 schools, faculties or degree programs of dentistry, of which 8 are financed by the state and the rest are privately managed. The curricular organization of degree programs is governed by the criteria established by the National Commission for the Evaluation and Approval of

Universities (CONEAU), which is responsible for the approval and qualification of the different educational options. There are different curricular options, some of which follow a flexnerian model, while others have incorporated modalities based on interdisciplinary integration following a sequence of increasing complexity5. Although there are criteria that enable the establishment of equivalence among these alternatives, no valid method has been developed that would enable the interinstitutional circulation of the students, guaranteeing a reasonable equivalence between the competencies certified by each institution6.

In the field of health, curricula based on disciplines independent of one another generally determine structures that hinder the integration of knowledge focused on the solution of complex problems. Comprehensive care clinics serve as a pragmatic projection of complexity7. Integration is not a consequence of the elimination of disciplines, but the approach to health problems as complex problems8,9.

Comprehensive care clinics are a useful tool in curriculum design, approaching health in its full complexity by using relevant interventions that require generic and subject-specific evidence-based competencies relevant to the context, and favoring meaningful learning for the actors involved.

In the present research, the objects of study are the so-called Comprehensive Clinics in the dental courses at public universities in Argentina. They were analyzed using theoretical triangulation and the comparative method. Triangulation is a heuristic process (principles, rules and strategies) aimed at documenting and contrasting information from different viewpoints. Hence, it is possible to distinguish different types of triangulation depending on the focus of comparison and contrast: techniques, agents, times, methods, or data analysis techniques.

Although there are four basic types of triangulation (data triangulation, theory triangulation, methodological triangulation, and investigator triangulation), Janesick10 and Cohen and Manion11 included interdisciplinary triangulation and time triangulation based on the simultaneous use of longitudinal and cross-sectional designs12. Analysis triangulation is the combination of two or more methods of analyzing a single group of data for the purpose of validation.

The comparative method has been applied in the field of education, with contributions based on the grounded theory methodology13-16. According to Arnal et al17, the application of comparative method enables the following to be distinguished:

a) incompatibility18, b) complementarity19, and c) epistemological unity20 among the comparative institutions or methods.

The aim of the present work was to identify the existing similarities and differences regarding the conceptual and methodological characteristics of the Comprehensive Care Clinic in the different curricula at state universities in Argentina.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analytical tools were designed and applied to compare the different comprehensive care clinics. We compared courses called Comprehensive Care Clinic in the curricula of eight Schools of Dentistry at public Argentine universities and identified congruence and divergence between them. The following institutions were analyzed:

Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBA)

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (UNC) Universidad Nacional de Rosario (UNR) Universidad Nacional de Cuyo (UNCuyo) Universidad Nacional de Río Negro (UNRN) Universidad Nacional del Nordeste (UNNE) Universidad Nacional de La Plata (UNLP) Universidad Nacional de Tucumán (UNT)

For the purpose of this study, the institutions were anonymized by using numbers to identify them.

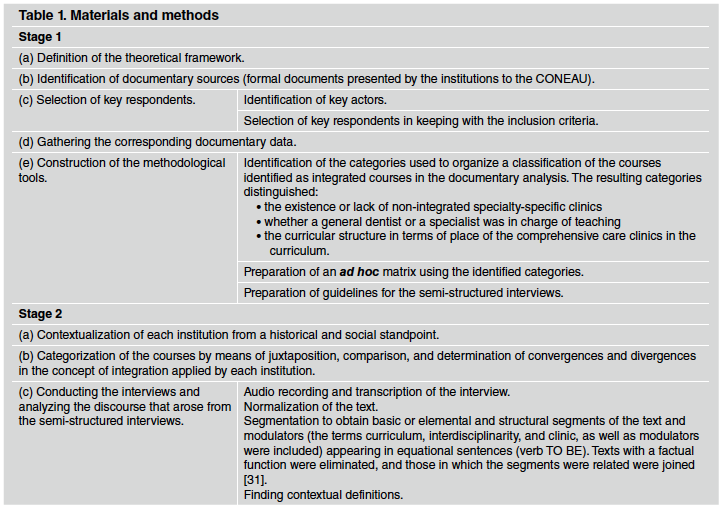

The methodology used is summarized in Table 1).

Stage 1

(a) Definition of the theoretical framework and identification of the documentary sources

The information was analyzed following criteria by Bray et al.21, which recognize three axes for the analysis. The 1st axis, defined as " Aspects of education and society", involved analyzing the clinical courses identified nominally or functionally as integrated courses providing different levels of care, and approved by the CONEAU (National Committee of University Assessment and Accreditation).

The 2nd axis, " Level of geographic location", involved identifying the corresponding province/ district with the aim of establishing epidemiological profiles that could influence prioritization of health problems.

Analysis of the 3rd axis, " Demographic characteristics", involved identifying clinics/ courses defined as comprehensive care clinics but excluding those specific to certain age group, gender or medical risk, as well as those specific to the incumbencies of the specialties.

(b) Selection of key respondents for the test interviews

Participants were selected by applying a proactive criterion, i.e., according to their knowledge of the subject22.

The following criteria were applied:

Inclusion criteria: having held a different teaching position between 2000 and 2015 and agreeing to participate in the study; participation was anonymous.

Exclusion criteria: having held a position in the governing body of their institution.

(c) Documentary data collection and analysis from the different institutions

(d) Methodological tool design

Identification of the categories used to classify the courses identified as comprehensive care clinics in the documentary analysis.

Construction of ad hoc matrices using the categories.

Preparation of rules for gathering and recording the data from the semi-structured interviews.

Stage 2:

(a) Contextualization of each institution was performed from a historic and social standpoint.

(b) Comparison of the courses proposed by the different dental schools was performed following the process described by Bereday 23 and other authors24,25. Juxtaposition enabled identification of the convergences and divergences between the concepts of integration applied at the different institutions and summarized in the matrices.

(c) Test interviews were conducted by a single researcher. From a total 3 teachers per institution, with different degrees of responsibility, one was selected as having more specific knowledge of the subject. Eight teachers with different degrees of responsibility were interviewed, one from each school. They were assured anonymity, and each interview lasted not more than 20 minutes.

(d) Test interviews were analyzed according to Magarinos de Morentin26 The aim was to identify the different meanings put forth by the respondent and that became apparent in the respondent's discourse during the interview. The following steps were used:

Tape-recording and transcription of the interview.

Normalization of the text.

Segmentation, to obtain the basic/elemental and structural units of the text, in addition to their modulators. The texts containing the terms curriculum, interdisciplinarity, clinic, and modulators in equational sentences (verb TO BE) were identified and included. Texts with a factual function were eliminated, and texts showing a relation between/among segments were joined27.

Contextual definitions, based on which conceptual axes were defined for the purpose of comparing the institutions.

RESULTS

Analysis and categorization arising from the available documents

Historical-contextual analysis

A general approach and an institution-specific approach were used.

Two events that affected all the studied institutions were detected in the general analysis:

Regulation of national universities linked to the

process of democratization of the country.

Creation and regulation of the CONEAU, in 1995 and 1996 respectively28.

The institution-specific analysis comprising the 1985-1995 period showed the following internal and external events to have had an impact on the curricular design of each institution:

Change of university authorities.

Projects with external funding at three institutions (Identified institutions as 1, 2, and 7)

Definition of the regulations regarding requirements for accreditation of degree programs and subsequent adjustments.

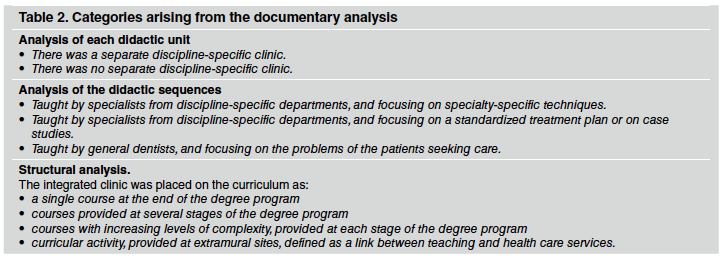

Structural analysis

The curricula of seven institutions included clinically integrated courses/comprehensive care clinics (Comprehensive Clinic, Social Practice, and so forth).

All institutions include more than one clinically integrated course or comprehensive clinic in their curricula.

The courses identified as comprehensive care clinics in the study plans corresponded to at least one of the following characteristics:

A single course at the end of the degree program.

Several courses taught at different stages of the degree program.

Courses with increasing levels of complexity, taught at each stage of the degree program.

Courses that were or were not included as a curricular activity, taught at extramural sites, and defined as a link between teaching and health care services.

Descriptive analysis of the courses and the didactic sequence (Table 2)

The following didactic modalities were detected:

-

The evidence-based theoretical contents were taught in separate courses,

-

The theoretical contents were taught in the clinically integrated course/integrated clinic

by specialists from discipline-specific departments (surgery, endodontics, etc.), focusing on specific techniques.

by specialists from discipline-specific departments, focusing on a standardized treatment plan or case studies.

by general dentists (family, community, etc.), focusing on the problems of the patients seeking care.

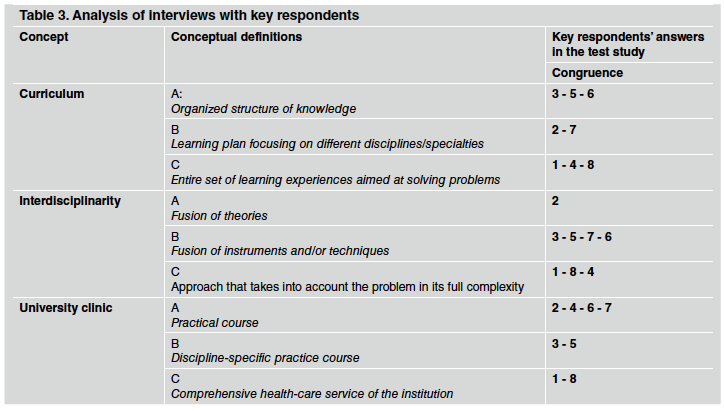

Interviews (Table 3)

Text normalization enabled the detection of subject-specific language resources, without performing normative adjustments.

Segmentation enabled the detection of 246 text segments.

Contextual definitions

The segments obtained enabled the detection of the different meanings/beliefs held by the respondent prior to the interview.

The characterization of the concept "curriculum" was identified in the texts and corresponded to one of the following descriptions29-31:

An organized structure of knowledge.

A learning plan focusing on different disciplines/specialties.

An entire set of learning experiences aimed at solving problems.

The concept "interdisciplinarity" was characterized as:

The fusion of theories.

The fusion of instruments and/or techniques.

An approach that takes into account the problem in its full complexity.

The concept "clinic" was characterized as:

A practical course.

A discipline-specific practice course.

A comprehensive healthcare service provided by the institution.

Divergences and convergences were observed in the conceptualization of the term "curriculum", "interdisciplinarity", and "clinic". Comparison of the conceptual definitions from the different institutions showed the following results:

Total convergence (convergence in all three conceptual definitions) was observed between two institutions (1 and 8).

Total divergence (no converge between any of the selected answers) was observed between two pairs:

Partial convergence in at least one of the three contextual definitions was observed in the following 8 cases:

Institutions 1 and 4

Institutions 7 and 2

Institutions 3 and 7

Institutions 3 and 6

Institutions 7 and 5

Institutions 7 and 6

Institutions 4 and 2

Institutions 8 and 4.

Partial divergence in at least one ofthe three contextual definitions was observed in the following 7 cases:

Institution 1 vs. Institutions 3, 6, 5 and 7

Institution 2 vs. Institutions 1, 8, 5 and 3

Institution 3 vs. Institutions 1, 8, 7 and 2

Institution 5 vs. Institutions 1, 8, 7 and 2

Institution 6 vs. Institutions 7; 2, 4, 1 and 8

Institution 7 vs. Institutions 1. 8 and 4

Institution 8 vs. Institutions 3, 6, 5 and 7.

DISCUSSION

Triangulation of data obtained in the present study showed that Comprehensive Clinics appeared textually in most curricula (7/8 schools), which can only be interpreted as appropriation of discourse. The convergences or divergences found during this study would seem to be the result of:

the paradigms in place or that serve as reference, and which the involved actors uphold,

the rationality of the actors involved, i.e., their capacity to think, evaluate, understand and follow a course of action in keeping with principles of consistency,

local realities governed by intellectual traditions that shape education (epistemological, organizational-institutional, subjective) and are perceived by those who have the habitus for recognizing and using such realities,

the styles and processing codes, whether inherited or emerging32,

The weight of the hegemonic institutions, the inadequate relation among ideologies (academic rationalism, social economic efficiency, social reconstructionism, orthodoxy, progressivism, cognitive pluralism) and the components of the curriculum (intentions, contents, teaching, learning and assessment methods). For the purposes of an evaluation of the courses, it would seem interesting to continue questioning the institutions about the significant weight of the "academic tribes" 33 or "the invisible school"11 in the university institutions in dispute for fields of work and allocation of funds. This phenomenon has been observed both in social and natural sciences5,9,33.

The didactic organization of the different curricula shows "who and what" are at the center of the teaching and learning processes:

The core actor is the discipline-specific teacher, and focus is placed on specific teaching techniques.

The core actor is the student, and focus is placed on learning standardized treatment plans or case studies, in which the theoretical contents are provided by discipline-specific teachers.

The core actor is the patient, and focus is placed on the patient's problems, which are usually complex.

This patient's problems must be solved according to the priorities that arise from the application of properly contextualized scientific evidence.

As tools for curricular organization, comprehensive care clinics are based on the concept of integrated and comprehensive healthcare services, and must include different integration circuits, i.e. horizontal, vertical, functional and virtual circuits. These circuits are generated through the relationships among all involved actors, and are not based on the weight of the knowledge contributed by each of the actors/teachers7.

It should be noted that the methodological tools became apparent in the test interviews aimed at identifying contextual definitions of basic concepts inherent to the study and the conceptual networks. These methods were useful to identify variables referring to the competencies that may be essential in the evaluation instances that lead to a reasonable comparison between the studied degree programs. The proper implementation of comprehensive clinics, keeping the focus on the patients and recognizing the complexity of the health problems they are going through, is an intervening variable in the achievement of the essential competencies.

This rigorous analysis is considered essential to the construction of questionnaires especially focused on the student learning process and its subsequent validations. The questionnaire or other instruments would enable the broadening of the different categories of actors and identification of the different conceptualizations and approaches used at each institution with regard to integrated learning and its various components.

In view of the characteristics of the conceptual networks identified in the present study, it would seem necessary to perform factorial studies (varimax or oblimin rotation) that enable the identification of the main components and factors that must be taken into account to facilitate the implantation of curricular changes and the identification of the intervening variables that affect the results of curriculum studies. The triangulation method used in the present study was useful to answer to the demands that higher educational institutions face today.

CONCLUSIONS

1. The method used here enables the following

conclusions:

Most curriculum documents stated the existence of clinical integration (7/8 schools).

There was divergence between the statements in the curriculum documents and the conceptualization on generic competencies to guarantee relevant learning.

The present qualitative analysis suggests that focusing on the problem/s of the patient seeking care as an issue relevant to the learning process had shifted, in several cases towards a teaching process which was strongly influenced by the teacher's personal values.

It seems recommendable to seek greater rigor in the different components of curricular integration, in line with international trends of university quality.

The present study enables us to recommend the application of this methodology in baseline institutional studies to identify the definitions and conceptual networks that are necessary to develop useful questionnaires for educational research and decision making.