Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Cuadernos de herpetología

versión On-line ISSN 1852-5768

Cuad. herpetol. vol.31 no.1 San Salvador de Jujuy mayo 2017

NOTA

Assessment of the calling detection probability throughout the day of two invasive populations of bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) in Uruguay

Gabriel Laufer1, Noelia Gobel1, Alvaro Soutullo1,2, Claudio Martinez-Debat3, Rafael O. de Sá4

1 Área Biodiversidad y Conservación - Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura. Montevideo, Uruguay.

2 Departamento de Ecología Teórica y Aplicada. Centro Universitario Regional Este - Universidad de la República. Montevideo, Uruguay.

3 Sección Bioquímica. Instituto de Biología. Facultad de Ciencias - Universidad de la República. Montevideo, Uruguay.

4 Department of Biology, University of Richmond. Richmond, EE. UU.

Recibida: 18/08/16

Revisada: 22/12/16

Aceptada: 28/12/16

ABSTRACT

Bullfrog invasion is a major conservation concern in South America, so there is an urgent need to detect and monitor its many invasion foci. Amphibian sampling methods commonly use calling display, specifically the nuptial calls of males. With the aim of obtaining the better day period to sample and monitor Lithobates catesbeianus presence, we recorded its calls at three ponds in two invaded localities in Uruguay (Aceguá, Cerro Largo, and San Carlos, Maldonado) during the reproductive season. Then, we studied the records, obtaining a subsample of calling intensity at the first 5 minutes for each hour. We detected that vocalization intensity remained almost constant between 20:00 and 05:00 h. Detection probability remained high and constant during this period, and then decreased. Therefore, bullfrog displays a constant calling activity during the nights of its reproductive period, even longer than native anurans. This long calling period facilitates its detection during nocturnal sampling.

Key Words: Invasion biology; Bullfrog; Sampling methods; Pond.

Knowing the natural history of an invasive alien species is essential, both to understand its impact and performance in a new environment, and to monitor it (Davis, 2009). The invasion of the American bullfrog, Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802), in South America is a major concern in conservation for its potential harmful effects on native biodiversity (Laufer et al., 2008; Akmentins and Cardozo, 2010; Nori et al., 2011; Ruibal and Laufer, 2012). One of the most notable attributes of the amphibians is their calling display, specifically the nuptial calls of males (Wells, 2007). L. catesbeianus displays a characteristic call, which gives its common name to be similar to the sound emitted by a bull, consisting of a loud call of between three and fifteen sequential vocalizations, with bimodal peaks at 0.2 kHz and 1.4 kHz. Silences periods between 0.5 and 1 second may occur among calls (Capranica, 1968).

Bullfrogs´ vocalizations occur over prolonged periods during the warmer months, in which males can call isolated or in large chorus (Emlen, 1976). The evidence gathered in the northern hemisphere shows that these calls occur during the evening hours, when water temperatures are higher than 20°C and under low wind conditions (Oseen and Wassersug, 2002). Recently, Medeiros et al. (2016) have found seasonal differences in the amount of males vocalizing per hour in an invasive population of southern Brazil. While in spring the average number of vocalizing males peaks their maximum between 18:00 and 0:00 pm, in summer this activity peak occurs between 2:00 and 6:00 pm.

Amphibian's vocalization is a useful tool for researchers because of its specificity. Recording males' calling activity during the breeding season is a suitable method for field sampling and monitoring. Sound sampling can be used to assess the distribution and progression of exotic invasive anurans (Heyer et al., 2014). While L. catesbeianus calling activity is well known for the northern hemisphere, it has barely been studied for invasive populations of South America. The idea of this study was to find the optimal time of the day for detecting this species during the reproductive season in invasive population of Uruguay.

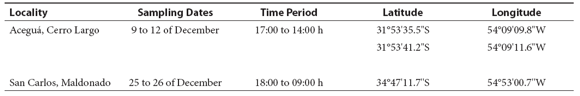

The field surveys were conducted by recording male bullfrog's calling activity in two lentic water bodies in the locality of Aceguá, Cerro Largo Department, and other one in San Carlos, Maldonado Department, in December 2015 (Table 1). In both sites recordings were made throughout the day with Panasonic RR-US310 recorders, located at 30 cm of the water bodies´ borders. Registration was performed continuously during the day, with a battery change every 20 hours. Air temperature and relative humidity at the edge of the pond, were recorded by data loggers (Extech RHT10). The same type of data logger, covered and submerged 15 cm, reordered water temperature. These environmental records were performed every 10 minutes.

Table 1. Water bodies where record sampling of bullfrog calls was performed during the sampled season in 2015. In each case the location, date and time of start and end of recording is detailed, and geographic coordinates.

Data analysis was performed with a sub-sample of the record (Table 1). We studied the sonorous records of five contiguous minutes, considering that this time is the minimum visit per point, in a rapid field sampling in search of the presence of bullfrogs. For each hour the first 30 seconds of the 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 minute was analysed, and the proportion of recordings with bullfrog calls was scored (vocalization intensity). Scores assigned values were between zero and three. Zero was assigned when there was a total absence of calls; one when one third of the 30 seconds record calling males, a score of two when two thirds of the 30 second interval record calls, and three when the entire period of 30 seconds registered bullfrog calls. Thus, six values for each hour interval were obtained, which were added to obtain the average calling intensity per hour and its standard deviation, as well as the environmental variables.

Climatic conditions during the sampling period were among the reported ranges for December in Uruguay (Marengo and Camargo, 2008; Rusticucci and Renom, 2008). Air temperature was around 20°C overnight and strongly increased throughout the day peaking at 15:00 hours. Contrary, humidity was higher overnight, falling in the hottest hours. The water temperature remained relatively constant throughout the day with small peaks associated with higher temperature hours (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Records of climatic variables during the sampled period for bullfrog vocal activity in Aceguá, Cerro Largo Department and San Carlos, Maldonado Department. The graph includes means values of air temperature and water, and relative humidity.

Male bullfrog's vocalizations were heard over the day except for a period between 13:00 to 16:00 h. Between 20:00 to 05:00 h vocalization intensity remained relatively constant at the highest levels. After 04:00 h there was a constant decrease tendency in the vocalizations intensities, disappearing completely at 14:00 h. Then at 17:00 h vocalizations started to increase until 20:00 h (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Mean hour vocalization intensity ± 1SD of Bullfrog calls in Aceguá, Cerro Largo Department and San Carlos, Maldonado Department, in December 2015. The white bars indicate the daylight hours and the gray bars indicate night hours.

The pattern observed in Uruguay is similar to that reported for the northern hemisphere (Bridges et al., 2000). Bullfrog male has a long vocalization period spanning practically overnight. Considering native anurans' natural history, it is notable that the period of maximum bullfrog calls is extensive and overlaps with the shorter periods of time used by native species (e.g. Bardier et al., 2014). The high density, intensity and duration of L. catesbeianus calls could alter the native acoustic niche, affecting native anurans. It has been reported that bullfrog vocalizations can interfere in the acoustic niche of native species of Hypsiboas in Brazil. This species alters its calling frequency in the presence of calling bullfrogs, with possible negative consequences on their reproductive fitness (Both and Grant, 2012).

Regarding bullfrog activity sampling periods, we could suggest that better day period to perform species detection by means of vocalizations will be between 20:00 and 05:00 h. We detect that vocalization intensities remained almost constant within this period (Fig. 2). Although during certain times of the day we could record bullfrog vocalizations, the probability of detection declines drastically.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Ruben Almeida, Ariel Landaburu and the Aceguá and San Carlos landowners, for their support during fieldwork, and Marcos Vaira for his contributions as Editor. GL and NG have postgraduate grants from the Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación ANII and the Programa de Desarrollo de las Ciencias Básicas PEDECIBA, Uruguay. GL is member of the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores SNI, Uruguay.

Literature cited

1. Akmentins, M.S. & Cardozo, D.E. 2010 American bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802) invasion in Argentina. Biological Invasions 12: 735-737. [ Links ]

2. Bardier, C.; Canavero, A. & Maneyro, R. 2014. Temporal and spatial activity patterns of three species in the Leptodactylus fuscus group (Amphibia, Leptodactylidae). South American Journal of Herpetology 9: 106-113. [ Links ]

3. Both, C. & Grant, T. 2012. Biological invasions and the acoustic niche: the effect of bullfrog calls on the acoustic signals of white-banded tree frogs. Biology Letters 8: 714-716. [ Links ]

4. Bridges, A.S.; Dorcas, M.E. & Montgomery, W.L. 2000. Temporal variation in anuran calling behavior: implications for surveys and monitoring programs. Copeia 2000: 587-592. [ Links ]

5. Capranica, R.R. 1968. The vocal repertoire of the bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). Behaviour 31: 302-324. [ Links ]

6. Davis, M.A. 2009. Invasion Biology. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

7. Emlen, S.T. 1976. Lek organization and mating strategies in the bullfrog. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 1: 283-313. [ Links ]

8.Heyer, R.; Donnelly, M.A.; Foster, M. & Mcdiarmid, R. 2014. Measuring and monitoring biological diversity: standard methods for amphibians. Smithsonian Institution. Washington. [ Links ]

9. Laufer, G.; Canavero, A.; Núñez, D. & Maneyro, R. 2008. Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) invasion in Uruguay. Biological Invasions 10: 1183-1189. [ Links ]

10. Marengo, J.A. & Camargo, C.C. 2008. Surface air temperature trends in Southern Brazil for 1960-2002. International Journal of Climatology 28: 893-904. [ Links ]

11. Medeiros, C.I.; Both, C.; Kaefer, I.L. & Cechin, S.Z. 2016. Reproductive phenology of the American Bullfrog in subtropical Brazil: photoperiod as a main determinant of seasonal activity. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 11, 2016. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201620150694 [ Links ]

12. Nori, J.; Urbina-Cardona J.N.; Loyola R.D.; Lescano, J.N. & Leynaud, G.C. 2011 Climate change and american bullfrog invasion: what could we expect in South America? PLoS ONE 6: e25718. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025718 [ Links ]

13. Oseen, K.L. & Wassersug, R.J. 2002. Environmental factors influencing calling in sympatric anurans. Oecologia 133: 616-625. [ Links ]

14. Ruibal, M. & Laufer, G. 2012. Bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus (Amphibia: Ranidae) tadpole diet: description and analysis for three invasive populations in Uruguay. Amphibia-Reptilia 33: 355-363. [ Links ]

15. Rusticucci, M. & Renom, M. 2008. Variability and trends in indices of quality-controlled daily temperature extremes in Uruguay. International Journal of Climatology 28: 1083-1095. [ Links ]

16. Wells, K.D. 2007. The Ecology and Behavior of Amphibians. University of Chicago Press. Chicago. [ Links ]