Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Share

Cuadernos de herpetología

On-line version ISSN 1852-5768

Cuad. herpetol. vol.31 no.2 San Salvador de Jujuy June 2017

TRABAJO

Color variation in Apostolepis nigrolineata (Serpentes, Colubridae: Dipsadinae: Elapomorphini), and contribution to the knowledge of the nigrolineata group

Thales Lema1, Albérico Nogueira de Queiroz2, Luciane Aldado Martins1

1 Vertebrate Systematic Laboratory, Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, P. O. Box 1429, 90619-900, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

2 Departamento de Arqueologia, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Av. Marechal Rondon, s/n, 49100-000, Jardim Rosa Elze, São Cristovão, Sergipe, Brazil.

Recibido: 09/08/16

Revisado: 22/12/16

Aceptado: 24/04/17

ABSTRACT

Color variation in A. nigrolineata was observed after examination of a large sample. The juveniles have five-stripes, lower sides yellowish cream, snout white, several white blotches on the supralabials, as well as on the nuchal region and the region in which other species have a white collar. The adults become dark, with the paravertebral stripes fading and eventually disappearing; the lower sides become blackish, sometimes forming a stripe under the pleural strip; the snout also darkening and becomes blackish; the supralabial blotches are reduced to small one during ontogeny, being oval, or trapezoidal, under the eye; the nuchal blotches are also reduced to a pair of oval blotches. The background coloration varies from brown to reddish during development. Juveniles from western Maranhão and adjacent areas of Pará are generally darker. The nigrolineata group is restricted to the Amazonian Forest, with the exception of one species that occurs in the northeastern enclave, remnant of the last Quaternary glaciations. A. nigrolineata differs strongly from A. quinquelineata, the latter being plesiomorphic and the former, and apomorphic in relation to it.

Key words: Amazonia; Ontogeny; Supralabial blotch; Collars; Tail blotch; Morphs.

INTRODUCTION

Apostolepis nigrolineata (Peters 1869) is the best-represented Amazonian species in collections, indicating that it might be abundant. By contrast, its congeners, Apostolepis quinquelineata Boulenger 1896, Apostolepis rondoni Amaral 1925 rev., Apostolepis nigroterminata Boulenger 1896, and Apostolepis sp. are very scarce in collections. We had the opportunity to examine a large sample of A. nigrolineata in the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG), the data of which were published by Lema and Renner (1998). In that sample, Cúrcio et al. (2011) detected another species, Apostolepis nelsonjorgei Lema & Renner 2004. In this paper, we selected the specimens determined as actually belonging to A. nigrolineata, to record color variation in the adults and also throughout development. Some photos of living specimens are also added to facilitate species identification. Apostolepis nigrolineata is the most frequent species in the Amazon Domain. It is sometimes mistaken for Apostolepis quinquelineata Boulenger 1896, a species that is very different in appearance, and has restricted distribution in northern Amazonas and adjacent lands. One difference between the two species is the absence of a tail blotch in A. quinquelineata, which may be a regression. The closest species to A. quinquelineata, is A. rondoni Amaral 1925, which is revalidated mostly because it has the tail blotch. One species of the group is endemic to the Serra de Baturité, Ceará, being very similar to A. nigrolineata, the main difference being the presence of very thin stripes which disappear in adult stage (in litteris). Another species is Apostolepis nigroterminata Boulenger 1896, from Peru and adjacent Brazil; it differs mainly by the presence of nucho-cervical collars. Apostolepis nigrolineata was analyzed by Felipe Cúrcio, from the University Fede ral de Mato Grosso (Cuiabá, Brazil), for a complete taxonomic assessment (in litteris).

The variation of each specimen was recorded in individual files (Lema and Renner, 1998) and the generalized aspects were presented. Here, we present the detailed aspects of variation color mainly the supralabial blotch which varies much during ontogenesis. The frequency of types and incidence of color variation occurrence were not recorded because variation is polymorphic in juveniles, becoming established in the adults. Data of the specimens were published in Lema and Renner (1998).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Specimens were observed directly at the Laboratory of Vertebrate Systematic of PUCRS and in the Laboratory of Herpetology of MPEG. Previously published data (Lema and Renner, 1998), not presented here, includes two types of forms, one with qualitative data and the other with quantitative data. The most important variation is commented, including detection of some morphs and rare anomalies. A large sample of A. nigrolineata was obtained thanks to the efforts of Otávio Rodrigues da Cunha, assisted by Francisco Paiva do Nascimento, both retired biologists of the MPEG now. They travelled on several roads of the state of Pará and adjacent Maranhão recruiting collaborators, to whom they gave plastic recipients of 50L with formalin 10% and collecting instructions. After some time, they returned to those places to pick up the specimens, who were then prepared and permanently stored in large glass cylinders with 70% ethanol Using this strategy, they obtained the largest known sample of Elapomorphini. This sample documents the local abundance of A. nigrolineata and the scarcity of A. quinquelineata. Three specimens of Apostolepis nelsonjorgei Lema & Renner 2004, which were erroneously determined as A. quinquelineata and later re-determined by Felipe Cúrcio (Cúrcio et al., 2011), were also re-examined.

Cunha and Nascimento (1978, 1993) considered all MPEG specimens as A. quinquelineata. We determined two morphs, which we called alpha and beta. The former corresponds to A. nigrolineata, and the latter to A. quinquelineata. More specimens from other institutions, viz. Instituto Butantan, Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia, Naturhistorisches Museum zu Wien, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Zoologisches Museum zu Berlin (see Appendix I), were also analyzed by us.

Three specimens found at the Universidade Federal do Ceará (LAROF.1349, 1950, and 2067), published as A. quinquelineata (Nascimento & Lima-Verde, 1989), were re-determined by the senior author as belonging to an unknown species (Loebmann et al., unpub. data), which is endemic to an enclave of the state of Ceará, Serra do Baturité.

Acronyms for institutions follow Sabaj-Pérez (2014); except: CEPB, Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas Biológicas, Universidade Católica de Goiás, Goiânia; CS, Christine Strüssmann field number, Cuiabá, MT; IMTM, Instituto de Medicina Tropical, Manaus; INPA, Instituto Nacional Pesquisas Amazônia; LAROF, Laboratório de Herpetologia, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza (= NUROF); LPH, Linha Pesquisa Herpetologia PUCRS (now in MCP); MZUFV, Museu Universidade Federal Viçosa; NUROF, Núcleo Regional de Ofiologia, Fortaleza, Ceará (= LAROF); WWF, Wild Life Foundation, Manaus; ZUFMS, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul.

RESULTS

General observations

(a) Specimens with five stripes are usually juveniles, whereas adults usually have three stripes. (b) In the sample from Maranhão, the paravertebral stripes with dark margins are evident in the adults, different from the majority of specimens from the state of Pará. (c) The stripes are blackish brown. (d) The paravertebral stripes have dotted margins and fade during development. (e) A comparison with other striped species of Apostolepis revealed that a reduction in the paravertebral stripes is frequent during the development of large specimens (Tables 1 and 2). (f) Females are larger than males (Tables 2 and 3). (g). All species of the nigrolineata group present a total or partial white nuchal collar, and in most of them it becomes only vestigial in adults. This fact suggests a collared ancestor.

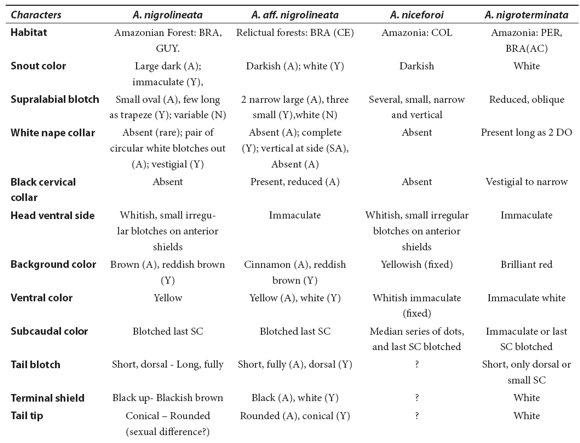

Table 1: Comparison of the Amazonian species of Apostolepis with major characters.

Table 2: Comparison of the species from nigrolineata group, including the new species. Abbreviations: A, adult; AC, anterior chin-shields; BRA, Brazil; CE, Ceará State, BRA; COL, Colombia; GUY, Guyanas, IL, infralabial shield; N, neonate; PER, Peru; R1 = SC/VE; R2 = TAL/TOL; R3 = TAL/SVL; SA, sub-adult; SC, subcaudal scale; SL, supralabial; SVL, snout-vent length; TAL, tail length; TOL, total length; VE, ventral scale; x, average; Y, juvenile.

.png)

Table 3: Statistics of measurements and number of ventral and subcaudal scales of a sample of Apostolepis nigrolineata. Measurements in millimeters; abbreviations: n, number of specimens; SVL, snout-vent length; TAL, tail length; x, average, SC, subcaudal scales; VE, ventral scales (From Lema and Renner, 1998, part)

Features of the holotype of Elapomorphus nigrolineatus Peters 1869 agree with the holotype of Apostolepis pymi Boulenger 1903 in many aspects. Therefore, both were synonymyzed with A. nigrolineata (Lema, 1997). The observed differences are due to individual variation, and several characters described by different authors, are common to many species of the tribe, and some are common to the genus. The high number of ventrals on the type- specimen (Peters, 1869) is very rare, which as noted by Lema and Renner (1998), who found up to 246 VE, in a very long body.

Another species, Apostolepis niceforoi Amaral 1935, described for Colombia, is the same as A. nigrolineata, at least based on the holotype, which was destroyed in the fire in Instituto Butantan. The original description is laconic and lacks some data, thus making this species invalid, and another synonym of A. nigrolineata.

Specific observations

Head dorsal side: The pileon is blackish brown, limited anteriorly, by the snout blotch, and posteriorly forming the nuchal ring with variable projections never reaching the gular region (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1: a. Variation of supralabial blotch, in order of development. b. Variation of tail blotch. c. Dorsal aspect of head pattern.

d. Ventral aspect of newborn (drawings: L. A. Martins).

Snout light blotch: A. nigrolineata presents a characteristic light blotch on the snout, from PF to RO, which is outlined by blackish brown, forming a polygonal figure (Fig. 2d). It is white in newborns, darkening gradually with age, becoming fully blackish in large specimens (Figs. 2e, 3b, 3c). The same happens in juveniles of A. nigroterminata Boulenger 1896 (Lema et al., in litteris). One variation is the presence of a small black blotch on RO, or the RO fully black, in which case the blotch is reduced to the PF.

Figure 2: a. Live newborn of A. nigrolineata. To notice the presence of white nuchal collar almost complete (Anonymous). b. Juvenile specimen from Montagne de Kaw, in Roura, French Guiana. c. Fixed sub-adult (MCP.9193) from Madeira Riverbank, Rondônia. To notice the dominant brown coloration (M. Di Bernado). d. Fixed sub-adult (MCP.9193) showing the characteristic white polygon on the snout, the total reduction of the supralabial blotch, and a pair of white blotches after the head, which are remnants of the white nuchal collar (Marcos Di Bernardo). e. Sub-adult from Parque Nacional do Trairão, Pará. To notice the snout becoming darker (Telêmaco Jason Mendes Pinto).

Figure 3: a. Live nascent adult from Guaporé Riverbank, Rondônia. b. Adult live specimen from, Belem, Pará. To noticed the dark snout (Breno Almeida). c. Adult specimen from Ilha do Outeiro, Pará. To notice the absence of paravertebral stripes (Marcos Di Bernardo). d. Live specimen of Apostolepís quinquelineata. To notice the absence of tail blotch (Omar Machado Entiauspe Neto).

Supralabial blotch: This is the most variable aspect of species coloration (Fig. 1a). In neonates and juveniles there is more than one blotch, or the blotch discontinuous, and it may coalesce with the snout blotch. We observed that the blotch can be very long in the early stages, shrinking gradually during development, and becoming only small, oval, white blotch under the eye. In juveniles, a long trapezoidal blotch is present (Figs. 1a, 2c), becoming shorter in large adults (Figs. 1a, 3b, 3c). For this reason, we characterize the species using only adults (Lema and Renner, 1998).

Head lower side: No variation was observed, with the basic whitish cream coloration becoming gradually yellow towards the VE. Exception occurs in neonates, which present small black blotches on the infralabial margins (Fig. 1d).

Nuchal white collar: The adult presents a single pair of nuchal white oval blotches, which disappear in giant adults (Figs. 3b, 3c). In neonates, and very early juveniles, the blotches are large and large and vertical, on the sides of neck (Fig. 1a); during development they become reduced, sometimes breaking down into two on each side; some specimens do not present light blotches on the neck (Figs. 3b, 3c).

Vertebral zone: The background coloration varies during the ontogeny, from yellowish (Fig. 2c) to brown (Figs. 2d, 2e), becoming reddish in latter stages the end (Fig. 3c), sometimes even dark (Fig. 3d).

Vertebral stripe: This is the narrowest and darkest stripe, as in most striped species of the genus. It reaches the median vertebral row of DO, and may reach the adjacent angles of the seventh rows of DO.

Light intermediary stripes: Most striped species of Apostolepis, have a linear light stripe between the paravertebral and pleural stripes, occupying one half of each row of DO. This are more evident in the early stages (Fig. 2c), darkening during development, and disappearing in the adult (Figs. 3c, 3d).

Paravertebral stripes: More evident in the early stages (Figs. 2c, 2d), fading during development, usually disappearing in the adult (Figs. 3b, 3d).

Pleural stripes: The widest stripe is darker on the upper margin than on the lower (Figs. 2c, 2d). They become more evident due to a light upper stripe that contrasts with the blackish margin of the pleural. In larger specimens, this stripe becomes is reduced to a linear stripe (Fig. 3c).

Lower pleural zones: Usually the zones under the pleural stripes are dark, sometimes blackish dark (Fig. 1a). In several specimens, the second row of DO is colored on the median line forms a stripe (Fig. 1). This is the case of the holotype of A. niceforoi, which may be a synonym of A. nigrolineata. Most specimens from eastern Maranhão are more colored in this area, apparently configuring a morph.

Ventral side: All observed have the venter immaculate, with the white basic coloration (Fig. 2c) replaced by bright yellow (Figs. 2d, 2e).

Tail blotch: This is another strongly variable feature (polymorphism) that is not subject to ontogenetic variation varies from a complete blotch (DO and SC) to one reduced to the dorsal side (DO), in length. It varies from long to short (Figs. 1b, 3a).

Terminal: The TE is stocky, with conic minute tip, without spine, varying from fully white to white tip only (Figs. 1b, 3a).

CONCLUSIONS

Apostolepis nigrolineata is frequent in the Amazon Forest Domain as shown by the MPEG collection, at least, in the Pará state (Fig. 1d). The great variation in the features of this species suggests that it became established in the area a long time ago. There are two species occurring in neighboring areas, A. nigroterminata (Fig. 5c) and A. niceforoi. Both are very similar to A. nigrolineata, belonging to the same group nigrolineata Lema 2003. Apostolepis nigroterminata is diagnosed by having nucho-cervical collars, which are absent in other species of the group, and having the polygonal snout figure (Fig. 2e). Apostolepis. niceforoi is not well known and is almost indistinct from A. nigrolineata. Its original description is short and the drawing of it is insufficient for reliable identification (Amaral, 1935). It is known only from the holotype, which was burned during a fire at Instituto Butantan. Other specimens were found and are being studied at the Universidade Federal do Acre, who prepared a communication about it (in litteris). The type-locality of A. niceforoi is La Pedrera, Colombia, at the border with the state of Amazonas, Brazil, where the Amazon Forest biome also occurs. The specimen erroneously reported from Duke Reserve in Manaus (Amazonas) by Martins and Oliveira (1998) belongs to A. nigrolineata. Several references to Apostolepis pymi, and most to A. quinquelineata (Fig. 5a), are references to A. nigrolineata, according to examination of figures and/or published data.

Figure 4: Schematic distribution of regions where specimens belonging to the Apostolepis nigrolineata group were found. Key: Apostolepis niceforoi (black circle), Apostolepis nigrolineata (circles), Apostolepis nigroterminata (black triangles), Apostolepis quinquelineata (squares), Apostolepis rondoni (triangles); triangle outlined is the occurrence of Apostolepis nigroterminata in Brazil.

Figure 5: a. Apostolepis rondoni from Rondônia. To notice the presence of the tail blotch, which is different from that of A. quinquelineata (Paulo Bernarde). b. Adult of Apostolepis nigroterminata Boulenger 1896, from Acre, Brazil (Danyella Paiva da Silva). c. Sub-adult of Apostolepis sp. endemic from Serra do Baturité, Ceará. To notice the vestige of the nucho-cervical collars (Daniel Loebmann).

Species of the nigrolineata group are distinctive by the stocky body in adults, the non protruding snout, the rounded head , the stocky and wide tail with a conic tip, and the polygonal figure on snout (Fig. 2b). The ancestor may have been widespread in the old Hylaea and, after the last glaciations, became isolated in small elevations in Ceará, where relictual forest existed. The Amazonian Forest is continuous from Brazil to Colombia and Peru, and A. nigrolineata disperse to the West, reaching southeastern Colombia (A. niceforoi), and to the Southwest reaching Rondônia and adjacent lands. We believe A. nigrolineata occurs in the whole Amazon Basin, but there are few samples from most of the area, and it is very extensive and sometimes impenetrable in many densely forested areas. The quinquelineata group is represented by A. quinquelineata (Fig. 5a) and A. rondoni (Fig. 5b) which are very small species, with five black permanent stripes and, light background color, sometimes yellowish or reddish orange. They are distributed in very distant populations, the former in northern Amazonia, and the latter in western Amazonia (Fig. 4).

Artificial key to determine the species of the Amazon Forest

1a. Vertebral color yellowish, five black stripes during all development; paraventral zones always immaculate whitish .....................................................2

b. Vertebral color brown, red to blackish, five stripes usually reduced to three in adults; paraventral zones immaculate whitish in early stages, later acquiring dots and/or dark stripes ..............................................3

2a. Tail blotch absent ...................... A. quinquelineata

b. Tail blotch present .......................... A. rondoni rev.

3a. Vertebral color brown in early stage of development, becoming bright red in adults ........................................................................... A. nigroterminata

b. Vertebral color brown in early stage, becoming reddish brown to darkish in adult ....................................................................................... A. nigrolineata

Voucher Specimens

Apostolepis niceforoi --- COLOMBIA: Amazonas: La Pedrera, Bajo Caquetá (IBSP.9197, holotype, lost).

Apostolepis nigrolineata --- (NNL.9218; ZMB.6447, holotype; ZMB.10739, Rohde Co., not Paraguay; NMW.21992, F. Steindachner col.). BRAZIL: (BMNH.1946.1.9.82, holotype A. pymi). Amapá: Macapá (IBSP.25514, ac. Ferrarezzi, 1993). Amazonas: (AMNH.101954, AMNH.101955); Manaus: INPA-WWF Reserve (INPA.1166, 'Apostolepis sp.', Martins & Oliveira, 1998); IMTM.1335, IMTM.1537, IMTM.1577, MZUSP.8423, MZUSP.8424, MZUSP.8657; AMNH.140772 (may be the same "A. flavotorquata lineata" ac. Ferrarezzi, 1993). Maranhão: Nova Vida: BR-316, 25 Km Gurupá River (MPEG.10199, 10202, 10204, 11136, 12274, 12286, 12295, 12663-12672, 13697, 13698, 13700-13702, 14409, 14780, 14781, 15004-15006, 15290-15292, 15758-15763, 16225-16229). Paruá: BR-316 [Pará/Maranhão] (MPEG.10835, 13641, 14352). Mato Grosso: Guaporé (CS.296). Pontes e Lacerda (NW Cuiabá): Triângulo Farm, near Guaporé x Madeira Rivers (CS.2500). Pará: (KU.127256, 127257, 128094). Acará Road: Pirajauara River (MPEG.10939). Apeú: Boa Vista (MPEG.586, 587, 696, 1174, 1476, 1479, 2657, 2666, 3331, 3332, 3334, 3335, 5718, 6916, 6919, 6943, 9459). Augusto Correa: Cacoal (MPEG.3905, 3954, 5399, 6712, 6713, 6721, 6724, 6737, 8999, 9937, 10764, 12450, 13074). Belém (IBSP.3033, 3034); Ananindeua, Maguari (KU.140153, 140154); Ilha de Mosqueiro (MPEG.12769-12771; IBSP.54152); IPEAN, 5 Km E Belém (KU.127256); Belém, Ilha do Outeiro (MCP.10718). Utinga, 5 Km Belém (KU.128094). Benevides (ZSM.137/11). Bragança: Bom Jesus (MPEG.1699, 1700, 1957-1959, 2216, 2217, 2237, 2238, 2973, 3046, 3047, 3050, 3670-3675, 3946-3948, 4361, 4364, 4384, 5029, 5030, 5037, 5110, 5116, 5119, 5125, 5127, 6322, 6332, 6334, 6352, 7929, 7930, 7932, 7934, 7935, 7937, 7942, 7947, 7954, 7959, 8239, 8240, 8245, 8249, 8251, 8268, 8270, 8273, 8295, 8563, 9951-9953, 9970, 12375, 13007-13009. Castanhal: Macapazinho (MPEG.5878, 7163, 7173, 10912, 10913, 11794, 12603). Colônia Nova: near Gurupí River, in BR-316 (MPEG.2174, 2970, 5160, 7821, 7827, 9546, 9558, 9818, 9829, 11486, 11488, 11933, 11937, 12882, 12883, 15060, 15063, 15863). Curuçá: Marauá (MPEG.4057, 4063, 4878, 4881, 4882, 4885, 4886, 5898, 5903, 5913, 7130, 7131, 7132, 7135, 7140, 7626). Curuá-Uma (MZUSP.8011). Fordlândia (IBSP.5126). Gurupá (MPEG.16324). Igarapé-Açu (MPEG.868-871, 910, 912, 913, 924, 925). Inhamgabi: Arraial do Carmo (MPEG.1464, 1568, 1571). Mangabeira (IBSP.48502). Marabá: Carajás, Serra Norte (MPEG.17304). Maracanã Road: Km 23 (MPEG.1596, 1600-1605, 1891-1897, 2101, 2422, 2423, 2560, 2822, 2826, 2864-2866, 3386, 3387, 3389, 3390, 3448, 3949-3951, 4086, 4094, 4801, 4802, 4807, 4808, 4811, 4813-4817, 4828, 4858, 8187. Osório: Limão Grande (MPEG.1658, 3945, 6150, 6187, 6197). Ourém: Limão Grande, Puraquequara (MPEG.4224, 5004, 5005, 5012, 7016, 7019). Pareci Novo (not Parci) (ZSBS[ZSM] w/n). Pratinha: Genipauba Road (MPEG.7570, 8399, 8615, 8631, 12571, 14285, 1546); Santa Bárbara (MPEG.1855, 2608, 3952). BR-316 [PA/MA] Km 74 (MPEG.1084, 3581, 8192, 10851). Santarém Novo: Trombetinha (MPEG.1841, 1977, 3251, 4154, 4796, 7081). Santo Antônio do Tauá (MPEG.1000, 1453, 1872, 1873, 1879, 2375,2376, 2643, 3306, 3940, 4718, 4720, 4721, 4723, 4730, 6958, 7557). Santa Rosa: Vigia Road (MPEG.3941-3944, 4614, 4615, 4617, 4620, 4642, 5656, 5665, 5666, 5683, 5685, 5686, 5690, 6774, 6792, 6799, 6802, 6887, 6984, 6988, 7487, 7497, 7537, 7542, 8490, 8514, 8517, 8551-8553, 8583, 9255, 9256, 9349, 10593, 10597-10599, 11835, 11836, 12590). Serra dos Carajás (MZUFV.1071). Uruá: Parque Nacional da Amazônia (IBSP.7285), near Tapajós River (MZUSP.7287). Viseu: Bela Vista (MPEG.1735, 2292, 2293, 3714, 5239, 5249, 7291, 7325, 7338, 7701, 8959, 11267, 11268, 15126, 15127); Curupati (MPEG.10010, 10884, 10886, 10887, 13260). Fazenda Real (MPEG.1787, 2323, 2324, 2349, 3142, 3143, 3953, 4458, 5320, 5321, 5324, 5325, 5327, 5329, 6633, 17279). Rondônia: Porto Velho (ZUEC, w. n.). Samuel: left Jamari Riverbank (CEPB.2851, 2852, 3060, 3111, 3162, 3227, 3321; MPEG.17817, MPEG.17879, MPEG.17880, MPEG.17982 MPEG.17983); Nova Colina (MZUSP.8513). GUYANA: (ZMB.6447, holotype A. nigrolineata); Georgetown: Wismar, Demerara River (FMNH.26665, re-det.); Upper Demerara, Berbice (KU.26665). SURINAME: Kaisenberg Camp, Zuid River (FMNH.121828, re-det., not A. flavotorquata acc. Van Wallach, 10/1995). )

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to collections managers, and colleagues who sent images; and to Oswaldo R. Cunha and Francisco P. Nascimento, for their attention and care at the MPEG and heir hospitality. to colleagues Marcos Di Bernardo (in memoriam), Christine Strüssmann, Paulo Bernarde, Breno Almeida, Fancisco P. Nascimento, Omar M. Entiauspe Neto, Telêmaco Jason, for photos or live specimens. To Patrick Campbell, from The Natural Museum of London, for the photos of the holotypes of A. pymi and A. quinquelineata. To Piter Keoma Bol by improvement of the english.

LITERATURE CITED

1. Amaral, A. 1935. Estudos sobre ophídios neotrópicos. XXXIII. Novas espécies de ophídios da Colômbia. Memorias do Instituto Butantan 9: 219-223. [ Links ]

2. Cunha, O.R. & Nascimento, F.P. 1978. Ofídios da Amazônia X. As cobras da região Leste do Pará. Publicacoes Avulsas Museum Paranaense Emílio Goeldi 31: 1-218. [ Links ]

3. Cunha, O.R. & Nascimento, F.P. 1993. Ofídios da Amazônia, X. As cobras da região Leste do Pará. 2nd ed. Boletin do Museo Paranaense Emílio Goeldi, Zoología 9: 1-191. [ Links ]

4. Cúrcio, F.F.; Nunes, P.M.S.; Harvey, M.B. & Rodrigues, M.T. 2011. Redescription of Apostolepis longicaudata (Serpentes: Xenodontinae) with comments on its hemipenial morphology and natural history. Herpetologica 67: 318-331. [ Links ]

5. Ferrarezzi, H. 1993. Sistemática filogenética de Elapomorphus, Phalotris e Apostolepis (Serpentes: Colubridae: Xenodontinae). Master Dissert., USP, São Paulo. [ Links ]

6. Lema, T. 1997b. A redescription of the tropical Brazilian serpent Apostolepis nigrolineata (Peters, 1869) (Colubridae: Elapomorphinae), synonymous with A. pymi Boulenger, 1903. Studies in Neotropical Fauna and Environment 32: 193-199. [ Links ]

7. Lema, T. & Renner, M.F. 1998. O status de Apostolepis quinquelineata Boulenger, 1896, A. pymi Boulenger, 1903 e A. rondoni Amaral, 1925 (Serpentes, Colubridae, Elapomorphini). Biociências 6: 99-121. [ Links ]

8. Martins, M. & Oliveira, M.E. 1998. Natural history of snakes in forests in the Manaus region, Central Amazonas, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78-150. [ Links ]

9. Nascimento, F.P. & Lima-Verde, J.S. 1989. Ocorrência de ofídios de ambientes florestais em enclaves de matas úmidas do Ceará (Ophidia: Colubridae). Boletin do Museo Paranaense Emílio Goeldi, Zoologia 5: 95-100. [ Links ]

10. Peters, W. 1869. Über neue oder weniger bekannte Amphibien des Berliner Zoologischen Museums. Monatsb. Akad. Wiss. Berlin 1869: 217-224. [ Links ]

11. Sabaj-Pérez, M.H. (editor). 2014. Standard symbolic codes for institutional resource collections in herpetology and ichthyology: an online reference. Version 5 (22 Sept 2014). American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Washington, D.C. Available at: <http://www.asih.org/ Last accessed in 10 June 2015. [ Links ]