The return of the state and the pink tide in Latin America: Implications for the capacity and democratic quality of gender equality agencies1

Around the turn of the millennium, Latin American politics radically shifted to the left, a process often labeled the pink tide (Cameron and Hershberg, 2009; Levitsky and Roberts, 2011). Despite their heterogeneous character (Beasley-Murray et al. 2009), these left-wing governments shared dissatisfaction with the neoliberal policies that dominated the region during the 1980s. Governmental agendas were reoriented towards developing policies to promote equality, social justice, inclusive citizenship, and new forms of democratic participation on the one hand (Levitsky and Roberts, 2011: 3; Reygadas y Filgueira, 2010; Iazetta, 2007), and stronger and more centralized states, with greater capacity to intervene and regulate the economy and society on the other (Cannon and Hume, 2012; Grugel and Ruggizoni, 2012, 2018). The dual agenda of strengthening state capacity and deepening democracy held some transformative promises for the architecture of feminist state-society relations and making progress towards gender equality and justice. Many of these new left governments voiced ambitions to reduce existing inequalities, to make the state more responsive to societal demands, and include social movement actors in building and monitoring political agendas and decision-making processes.

At the same time, the historically troubled relationship between the left and feminist movements in Latin America gave little reason for optimism that such drastic change would take place. Leftist politics in Latin America historically always had a complex and often contradictory relationship with women’s struggles (Friedman, 2009; Gago, 2007; Heumann, 2014). The regional track record of left-wing governments in making gender equality a policy priority has been poor as feminist demands have often been reduced to a “theme”, making gender equality objectives a theme of less priority in left-wing political agendas (Rostagnol, 2017). Also, left-wing governments have tended to marginalize body politics (sexuality and reproductive rights) (Corrales, 2015; Blofield and Ewig, 2017) or making invisible the domestic and informal economy in which women predominate (Gago, 2007; Giron and Correa, 2017). Now that the pink tide appears to be over (Rojas, 2017) and the region is facing a new wave of rightwing regimes promoting very conservative gender agendas (Blofield, Ewig, and Piscopo 2017; Biroli and Caminotti, 2020), feminist scholars are assessing the implications of the pink tide for gender equality and feminist activism in comparative perspective (Friedman, 2019; Blofield, Ewig, and Piscopo 2017).

So far relatively little attention is given to the implications for gender equality agencies (but see Rodríguez Gustá, Madera and Caminotti, 2017; González, 2020). This article seeks to contribute to this scholarship by assessing in what ways configurations of feminist state-society relations altered during the pink tide and what potential resilience or protection such changes may offer to prevent erosion of women’s rights. In particular I examine the implications of the pink tide dual agenda of strengthening state capacity and deepening democracy for gender equality institutions and governance structures in the region (Guzmán, 2001; Fernós, 2010; Guzmán y Montaño, 2012). I assess the strength and democratic quality of national gender equality institutions/institutional mechanisms for the advancement of gender equality as a measure of (1) the capacity of the state to intervene in gender and sexual relations and (2) the degree of access and influence of contemporary women’s rights movements to the state and policy-making processes. By doing this I try to answer the following questions: What are the consequences of the state reconfiguration and the increased presence of the state on the institutionalization of gender? Do we see more inclusion and participation of civil society in gender equality agencies?

The paper proceeds by first discussing the emergence and promises of the pink tide and then exploring the implications of these new left ambitions for gender equality and feminist agendas. I briefly discuss the development of gender policy machineries in the region, before outlining my comparative framework and the four cases under scrutiny: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Ecuador, each representing a different type of new left regimes. My empirical analysis of these four cases reveals large variations in how statemovement configurations developed in terms of women’s policy agencies’ capacities and participatory structures. The final section discusses the empirics comparatively and draws some theoretical conclusions.

The emergence and promises of the pink tide

The emergence of the ‘pink tide’ has been located in the failures of neoliberalism and ‘democratic disillusion’ towards the political system which promoted it (Barrett, Chavez, and Rodríguez -Garavito, 2008; Ruckert et al., 2017). The economic crisis that started in the late 1990s eroded the popular support for neoliberal policies (Panizza and Yanez, 2006). This rejection of neoliberalism was led by new political and social movements which emerged during the neoliberal era. New left-wing governments that came to power as a result of this crisis sought to break with the neoliberal macroeconomic policies that tended to reduce the role of the state and deregulate financial and labor markets that dominated the region after the Washington consensus.

The pathways to power of these new left governments varied through-out the region (Levitsky and Roberts, 2011). In the Andean region, new left mobilizations emerged outside of the political establishment as part of a popular backlash against ruling political elites. In contrast, the left in the Southern Cone followed an institutional pathway to power. Unlike the Andean region, democratic institutions were not in crisis and the party system remained stable. These different pathways to power and the historical legacies of the left across the region influenced the policy options and approaches of the new left regimes. Left governments varied both in their socioeconomic policies, their vision of the role of the state, and approaches to democratic governance.

While approaches differed, the agendas of the new left governments shared several commitments. First of all, left governments sought to counteract the perceived increase in inequality and poverty from the neoliberal era. They shared the central aim to combat social and economic inequalities through the redistribution of wealth and income to lower-income groups, erode social hierarchies, and improve the position of marginalized groups in society and in the political process. Moreover, they sought to enhance opportunities for disadvantaged groups and provide social protection against market insecurities (Levitsky and Roberts, 2011; Ruckert et al., 2017). Several studies indicate that governments of the left in the region indeed were more successful in their attempts to reduce inequalities compared to non-left governments (Cornia, 2014; Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni, 2017).

Second, in the political realm, the left sought to enhance the inclusion of marginalized groups through democratic reform and increased participation of civil society actors/social movements in policy processes (Lievesley and Ludlam, 2009; Panizza, 2009; Álvarez et al., 2017). This search for deepening democracy resulted in attempts of new left governments, to greater or lesser degrees, on a local and/or national level, to reorient state-civil society relations by facilitating greater civil society influence over policy-making processes, resulting in more emphasis on social policies to lessen poverty and inequality (Álvarez et al., 2017. In these attempts, governments often struggled to find a balanced relation with certain social movement sectors and avoid polarization (Beasley-Murray et al. 2010; Panizza, 2009). Also, they tried to incorporate social movement activists in state institutions, which resulted in demobilization and a decrease in critical distance.

Third, left-wing governments aimed to expand the role of the state in regulating state-market and state-society relations, labeled as a “return of the state” by some authors (Grugel and Riggirozzi, 2012; 2018). New left governments expressed their political aspirations to rebuild and reclaim the state, which was intended to be more than just a return of the state to the market/economy, but aimed to establish a new pact between society and state (Ibid.). Nowhere these aspirations resulted in a radical statist project (Beasley-Murray et al., 2010), yet important attempts were made to recentralize authority by reversing decentralizations of the 1980s and 1990s. The expansion of the historically weak states in the region was viewed as an important precondition for improving democratic governance, ensuring necessary means to guarantee the rule of law, to protect the rights of citizens, and to regulate economic transactions (Linz and Stepan, 1996; O’Donnell, 2001, 2004; Przeworski, 2010). Yet, the dual agenda of articulating participatory democracy and expanding the role of the state also created some potential tensions and contradictions. Tilly in his book Democracy argues that deep democracy requires state capacity “to supervise democratic decision-making and put its results into practice” (2007: 15). Rather than a static characteristic of states, Tilly views democracy as a continuous and dynamic process of changing political relations between state and citizens (2007, pp. 13-15). More democracy, for Tilly (2007:14) means a net movement toward broader, more equal, more protected, and more binding consultation. On one hand, democratization is reinforced by an increase in state capacity, as state expansion generates resistance, bargaining, and provisional settlements. While on the other hand, democratization encourages demands for expansion of state intervention, which promotes a stronger state capacity. Yet, when state capacity develops farther and faster than democratization, the path to democracy bifurcates to authoritarianism instead. Also, if democratization develops farther and faster than capacity and the regime survives, the path then passes through a risky zone of capacity building. These tensions are evident throughout the region. The state has become the “strategic terrain” of social and political struggle, blurring the traditional liberal divide between state and civil society (Cannon and Hume 2012: 34). Social movements potentially can transcend the narrow role assigned to civil society in liberal theory pushing the state to ‘alter the balance of social forces’ and making policy processes more accessible and participatory (Cannon and Hume 2012: 11). Yet, as it appears, this promise of a renewed contract between civil society and the state was not realized in most countries.

Gendering the pink tide?

The ambitions of new left governments potentially created the necessary conditions to advance gender equality and justice. Gender equality requires an effective state, capable of intervening in society, in the workplace, and in the domestic realm to strengthen the position of women and prevent sex discrimination (Htun and Weldon, 2018). In countries with weak political institutions, governments are unable to coordinate policy responses across levels of government (vertically) and departments and ministries (horizontally) and effectively implement and enforce policies. Implementation of policies to combat violence against women in Latin America, for example, has often been poor because of weak state capacity (Franceschet, 2011). Also, women’s interests and feminist issues must be effectively brought into state institutions and policy processes. It is, therefore, necessary to create effective mechanisms that facilitate access of social movements to policy-making processes and to channel their demands and ideas to state and policy agendas. In this sense, the political agenda of the new left had the potential for a new praxis -new gender equality agendas, policies, and institutions- and new relations between feminist actors and states. Yet, at the same time, feminists historically had little reason for such optimism. The relationship between the women’s organizations and the left in Latin America has been riddled with tensions and struggle (Friedman, 2009; Heumann, 2014). While feminists and the left can be seen to share a commitment to challenging the important historical inequalities in the region (Giron and Correa,2017), left-wing parties and governments only incorporated some feminist demands and have subordinated feminist issues to ‘larger’ goals (Friedman and Tabbush, 2019). The feminist agenda for social change proceeded without much overt support from the left (Friedman, 2009; Blofield, Ewig and Piscopo, 2017). Available feminist studies on the gender policies of the new left-wing governments in the region pointed to their contradictory and uneven responses to feminist demands (Biroli and Caminotti, 2020; Blofield, Ewig, and Piscopo, 2017; Friedman and Tabbush, 2019. These studies showed mixed results: some progress is made in terms of women’s welfare and representation, but far less with sexual and reproductive rights. More importantly, feminist scholarship makes clear that relations of new left governments and feminism throughout the region are multiple and levels of responsiveness towards feminist demands vary greatly. Blofield, Ewig and Piscopo (2017: 362) argue that pink tide governments can be best labeled as reactive left, not having any clearly articulated gender equality agendas, but mostly reacting to domestic gender equality activism. Patterns of policy progress are, however, not only explained by differences in the strength and autonomy of feminist mobilization, but party ideology, left party type, and policy domains also are important to explain variation in gender equality progress during the pink tide.

This complexity and multiplicity of state responses to feminism and state-movement relations thus require a careful and multidimensional analysis of the performance of new left governments in the transformation of gender and sexuality relations. Moreover, we are dealing with a “moving target” as relations between women’s organizations and governments are far from stable and opposition to gender equality and sexuality rights is also becoming more organized and mobilized throughout the region (Friedman, 2019; Biroli and Caminotti, 2020).

The institutionalization of relations between states and feminist movements

Feminist scholars see the state as gendered, and an important vehicle to reproduce gender relations in society. Gender relations imbricate in state policies and institutions. States perpetuate and enforce existing gender inequalities of status and resources. Yet, increasingly feminists have also come to view the state´s potential to challenge gender regimes and power relations, and feminist activists started to work to instate practices and rules that recast the gendered nature of the political (Beckwith, 2013:132-133). In the 1980s and 1990s, women’s movements across the globe managed to push states to develop policies and laws to promote gender equality. Governments in many countries responded, in different ways and to different degrees, by developing a set of agencies and mechanisms to take responsibility for such demands, the so-called women’s policy or gender equality agencies (McBride and Mazur, 2010).

These gender equality agencies (GEAs) vary in scope, size, resources, stability, and location. According to Lovenduski (2008), these GEAs can be seen at least in symbolic terms, as an acknowledgment of women’s demands for representation. The actions of these agencies and mechanisms are an important instrument to include women’s movement demands and actors into the state and so produce feminist policy outcomes (McBride and Mazur, 2010).

Mechanisms for the advancement of gender equality were developed relatively late in Latin American and Caribbean countries due to the presence of antidemocratic and authoritarian governments or violent political struggles (Guzmán, 2001). The first mechanisms were established in the 1970s (Belize, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Puerto Rico) and 1980s (Brazil, establishing a separate entity, and the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Panama, and Uruguay as part of a ministry) after transitions to democracy and in response to the demands of active women’s movements. Throughout the 1990s, the preparations for Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing provided an additional crucial impetus for other countries in the region to establish national mechanisms (Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Paraguay, and Peru). These mechanisms varied strongly across the region, not only in the location and rank within the governmental structure but also in terms of their acceptance as a legitimate governmental entity and the roles, mandates, and responsibilities entrusted to them (Guzmán 2001; Fernós, 2010; Guzmán and Montaño, 2012; Rodriguez Gustá et al., 2017). Also, these mechanisms were developed within difficult social and economic contexts. In particular, the policies of structural adjustments that the countries of the region faced, implied a decrease of resources or mergers with other ministries and political subdivisions and negatively affected their position, mandate, and resources. As a result, national mechanisms often exist as precariously, threatened political spaces, yet in some countries where the mandate of national mechanisms is established by organic law (Chile, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Paraguay, and Puerto Rico), these mechanisms enjoy a greater degree of stability and independence to the political pressures and changes in government (Fernós 2010: 29). Existing scholar-ship makes clear that relationships between left-wing governments and GEAs are not clear cut. Rodriguez Gustá, Madera, and Caminotti compare the machineries of Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, and Uruguay which during the pink tide indeed experienced some improvements in terms of formal hierarchy, promoting gender equality plans and establishing coordinating mechanisms and councils. Yet, they also argue that “governments did not uniformly decide that strengthening gender policy machineries was a priority” (2017: 472). Hence, their results remain inconclusive. My study complements their results but particularly focuses on the questions if and how pink tide dual agenda of strengthening state capacity and deepening democracy affected gender equality institutions and governance structures. Returning to Tilly’s insights about deep democracy and democratization as a constant process, these two dimensions should operate in tandem, but there are also potential tensions between them.

To measure both the capacity and the democratic quality of the different institutional mechanisms, I take several indicators for each dimension, based on the insights of feminist scholarship on the relations between gender, and state relations and, policy-making. To move from qualitative descriptions to comparison and to visualize patterns of change both within and between countries I operationalize the two dimensions each consisting of several indicators into numerical scales. For each indicator I assign a numerical scale ranging from 0 to the lowest value ever observed and 1 to the highest value, then I accumulate the four ratings into a single score. For each country, I compare the moment before a pink tide government took office, a second moment after five years of governing and a third moment 10 year later. The numbers assigned to each indicator for the four countries over time can be found in the annex.

1. The capacity of gender equality mechanisms to influence public policies.

The first dimension consists of four indicators to measure the capacity of state/institutional mechanisms to advance GEAs to influence political processes, in particular, to propose, elaborate, implement and evaluate public policies. These variables are strongly interrelated and are not exhaustive. In addition, it must be noted that these are determined by contextual and temporal differences.

a) Resources. This first variable is closely connected to but not similar to the second variable of role and functions. While the quantity of resources is not a determining factor in agency success in influencing policy or opening up politics to gender issues, more staff and higher budgets may mean an agency is better able to attain its goals and can do more to support women’s movement organizations, conduct research, and provide services. Three aspects should be considered: administrative capacity (budget and human resources), internal inversion (capacity/expertise building within the organization, data-gathering, and research), and external inversion (providing funding and support to civil society organizations). I assign 0 to a decrease in resources, 0,5 to stability or incremental increase and 1 to substantial increase.

b) Mandate and policy powers of the agency. Here machinery success occurs when agencies have clearly defined mandates and missions that are unambiguous. I distinguish between three central roles that agencies may play: 1) the capacity to monitor the progress of gender equality policies and or evaluate policies; 2) the capacity to propose and articulate policies; and 3) the power to execute policies that can be considered the most comprehensive role. I assign 0 to agencies that mainly supervise or monitor policy, 0,5 to agencies that can propose policies, and 1 to agencies that also execute policies.

c) Organizational stability/duration: this factor is both important for the legitimacy and access of the agency/mechanism within the administration. A policy agency that often changes in place, mandate, and personnel is less likely to play an influential role in the policy process. Here I also consider whether an agency has been created by presidential decree or law. An agency that has been created by law is more guaranteed to survive with changing governments. I assign 0 to agencies that exist less than five years and 1 to five years or more.

d) Location of the agency and placement of agency in relation to policy subsystem where a decision is made. Machineries that are located in the highest level of government, close to where important decisions are made will be more likely to be successful. Many studies on the developing world identify this as an important ingredient to more success. Also, policy subsystems that include elected leaders may privilege quasi agencies or cabinet offices; administrative offices may be important if the policy subsystem is in bureaucracy. I assign 0 to agencies that are situated outside ministries, 0,5 when located at the ministerial level, and 1 when located at the office of the executive/president.

2. The capacity of the agency/mechanism to channel feminist demands

To measure the democratic quality and capacity of women’s policies agencies/gender equality mechanisms, I look at both the dynamics and mechanisms initiated and used by the agencies to identify and capture democratic demands and the mechanisms to channel these demands and include perspectives and interests into policy processes. According to Tilly, a regime is democratic “to the degree that political relations between the state and its citizens feature broad, equal, protected and mutually binding consultation” (2007:13-14). Based on this definition I identify four indicators:

i Qualities of agency directors/ministers. Important factors include the leader’s commitment to gender equality goals, priorities set for the agency, and their political relationship with decision-makers and potential allies. Here I assign 0 to directors with no previous gender expertise or feminist profile and 1 to directors with wide experience and expertise, including a broad intersectional perspective on gender equality issues.

ii Meaningful/strong links with civil society groups: Collaborative “strategic partnerships” between agencies and women’s rights groups are identified as being conducive to success in Latin America and the Caribbean (Franceschet, 2007). This scale ranges from no links to women’s rights organizations (0) to some regular meeting and consultation of civil society organizations (0,5), to strategic partner-ships between a broad (intersectional) range of women’s rights organizations (1).

iii Mechanisms of citizen’s access and or consultation: here Tilly’s idea of a broad, equal, protected and mutually binding consultation of the citizenry is central. I distinguish between different degrees of accountability mechanisms indicating that women’s policy machineries can speak for and/or represent them access: information centers, ombudsman, or other places to make demands to the state, consultation, or deliberative mechanisms. (Htun and Weldon, 2018). Here the range is from no accountability mechanisms (0) via one-way accountability (0,5) to accountability and protected consultation (1).

iiii Relations between the agency and women in the legislative: Here I take into account descriptive representation of women, but also to some extent substantive representation by looking if and how women’s interests are channel and articulated through women’s parliamentary caucuses. I assign (0) when the percentage of female representatives is below 30%, to a representation over 30% (0,5), and a high representation combined with a women’s caucus (1).

Case selection

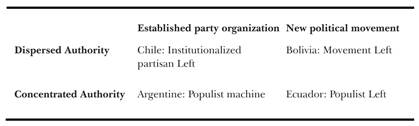

As both feminist and mainstream studies make clear, the label “pink tide” obfuscates the variation between these regimes. I propose to compare the different and changing WPA configurations in four Latin American countries that, according to the typology of left governments of Levitsky and Roberts (2011), respond to different types of left regimes. In trying to move beyond a dichotomous understanding of left-wing regimes that dominates the literature on the new left, Levitsky and Roberts (2011) propose a more complex understanding to capture the diversity of Latin American cases looking at two dimensions: (1) the level of institutionalization and (2) the locus of political authority. This allows me to explore the implications of these different left-wing regimes and their diverging paths to power, either emerging from a break-down of the traditional party system (Bolivia and Ecuador), or a continuation of institutionalized party politics (Argentina and Chile).

The first dimension of Levitsky and Roberts focuses on the level of institutionalization of WPAs. In the Latin American cases, did the emergence of new political movements that developed outside of the traditional political establishment allow for more access and influence of social movements in the new regimes, for instance? According to Levitsky and Roberts, the crisis-outsider path of Bolivia and Ecuador created incentives and opportunities for more transformative governance strategies and institutional change, for instance through “refounding” constitutional orders. The models of Bolivia and Ecuador potentially allowed for more access of social movements and more radical participatory models, whereas the more institutionalized regimes of Argentina and Chile may have developed stronger and more effective gender equality institutions.

The second dimension of Levitsky and Roberts focuses on the locus of political authority: whether power is concentrated in the hands of a dominant personality or dispersed more broadly within a party organization or social movement networks. In regimes where power is concentrated, support for gender equality issues and movement will depend a lot on the personal preferences of the leader; whereas regimes with dispersed power leaders are held accountable to the broader interests of parties or movements, and this makes possible the pressure to prioritize gender equality goals may come from below.

Source: Levitsky and Roberts (2011).

In addition, this selection of countries makes it possible to compare two cases with a female executive (Chile and Argentina) and two cases with a male executive (Bolivia and Ecuador) and allow me to contribute to debates on the gendered nature of the executive and institutional change (Waylen 2016). Given the powerful policy role of executives in Latin American governments, a sympathetic president can make an enormous difference. Yet, a female executive does not at all guarantee that gender equality becomes a policy priority or that women’s interests will be better represented and heard. For instance, Chilean President Michelle Bachelet (2006-10 and 2014-2108) made important efforts to improve the position of women, while Argentinean President Christina Fernández de Kirchner was not particularly concerned with gender equality issues.

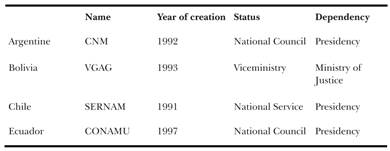

As the table below indicates, women’s policy agencies in the four countries vary in the date of creation and their original status/location. As we will see below, only the CNM and SERNAM in Chile kept their original names in the period of study, but this does not imply they have also maintained their position, resources, and mandates. The mechanisms in Bolivia and Ecuador have been replaced by several other mechanisms since their creation and also during the period of study in which I look at GEA configurations at three moments. The first moment is 2005, so just before new left governments took office in the four countries, the second moment in 2010 and the third moment is towards the end of the pink tide in 2015.

How did the pink tide influence GEA configurations?Comparing Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Ecuador

Argentina

The Argentinean Consejo Nacional de Mujeres (CNM), since its inception in 1992, had a weak structure, few resources, very little influence within the state, and no legislative role at all, leaving advocacy groups without influential insider allies (Rodríguez Gustá and Caminotti, 2010; Lopreite, 2015; Rodriguez Gustá, 2018). Radical change took place after the period under study in this article. Between 2017 and 2019, the institute has undergone a number of transformations leading to the establishment of the Ministry of Women, Genders and Diversity (Ministerio de las Mujeres, Géneros y Diversidad), meaning an upgrade in capacity, resources and protagonism and with a feminist leadership (Canelo, 2021). Yet, during the period studied in this paper, CNM remained a weak institute and its capacity not improve with the left-wing administrations of Nestor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Instead, Nestor Kirchner downgraded the CNM by giving it a new role and mission within the Consejo Nacional de Coordinación de Políticas Sociales (National Council for Social Policy Coordination), which was originally headed by his sister, Alicia Kirchner. This repositioning not only lowered CNM’s status and budget but also affected its capacity to channel feminist demands. Nestor Kirchner appointed Maria Lucila Colombo as the new president of the CNM. Colombo had been an activist in the Sindicato de Amas de Casa (Housewives’ Union) and had adopted an antiabortion position in the legislative debate on reproductive health when she was in the Buenos Aires city legislature in 2000 (Rodriguez Gustá, 2018). Under the administration of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner CNM’s resources slightly increased as a result of the agency’s role in distributing conditional cash transfer programs, yet, she zeroed out the National Women’s Council’s operating budget and leaving it ineffective (Franceschet, 2010). She had no interest in gender issues and followed a largely conservative agenda (Piscopo, 2014).

The democratic quality of the CNM had always been low and remained low under Kirchner governments. Under the Kirchner administration it had little power to affect the formulation, design, and implementation of public policies. Rodriguez Gustá, Madera and Caminotti (2017) therefore labeled CNM as a ceremonial machinery, lacking bureaucratic capacities and instruments to implement policies or promote women’s rights in practice. In terms of capacity to channel feminist demands, CNM fared very poorly. It had no formal or informal consultation spaces and did not actively involve women’s rights organizations in its planning and decision making (Rodriguez Gustá et al., 2017). Lopreite (2015) noted some short-lived efforts to reach out to grass-roots organizations in the context of an anti-poverty program when CNM offered some training workshops to these organizations.

The existence of these weaknesses at the national level facilitated their reproduction in provinces and municipalities, repeating the same structures, with little or no budget at all and very tight into their scope. If we consider the different indicators of the institute’s capacity and power to channel civil society demands in the policy process, we see that during the new left governments of Kirchner and Fernandez state feminism did not increase. CNM’s capacity to push for gender equality policies remained very low. The graph below captures the institutional changes of CNM between 2002 and 2015 both in the dimensions of democratization (channeling feminist demands) and institutional capacity. While institutional capacity remained very low in this period, a slight increase in democratic quality can be noted which was only a result of the increased political representation of women in the legislative and the creation of a women’s caucus (bancada feminina) but was not the result of more deliberative or participative mechanisms in processes of public policy-making.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Bolivia

Bolivia created a women’s policy agency in 1993 with few resources, very little influence within the state, and no legislative role at all. Over time this machinery remained notoriously fragile and suffered from institutional instability. The MAS administration of Evo Morales engaged in limited efforts to improve the institutional mechanisms to promote gender equality, despite its ambitious redistribution agenda. The Morales government dismantled the existing state machinery, the Vice-Ministry on Gender and Generational Affairs within the Ministry of Sustainable Development, and created a new Office on Gender and Generational Violence in the new Vice-Ministry on Equal Opportunities. The new office had limited decision-making authority, lacked human, technical and financial resources, and operated at the lowest level of the organizational and structural hierarchy of the Ministry of Justice (Rousseau and Ewig 2017). Due to this, it was unable to intervene in national processes nor to coordinate with gender mechanisms and bodies operating at the subnational level in the context of the process to increase the autonomy of local communities.

Furthermore, the Bolivian government created an Office for Decolonization within the Ministry of Cultures, headed by a Deputy Minister. Within the Office, there was a Depatriarchalization Unit, whose mission was to “depatriarchalize the colonial and neoliberal State, family life, society and religion” (Diaz Carrasco and Agar Diaz, 2013). The Unit’s objectives included “exposing and destabilizing patriarchal relationships and making them untenable, as well as transforming existing power relations in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, in order to construct a just and harmonious society”. Both the Gender Unit and the Depatriarchalization Unit had relatively low status in the State apparatus and lacked the resources to fulfill their mandates and create new intersectional public policies (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017).

When it comes to their democratic quality the gender equality mechanisms fared better. A partnership was been formed between the Ministry of Justice through the Office of the Deputy Minister for Equal Opportunity, the Platform of Women Assembly Members (with 28 representatives), the Comité Impulsor de la Agenda Legislativa desde las Mujeres (Action Committee for a Women’s Legislative Agenda, which brings together 28 NGOs and women’s organizations) and the Alianza de Organizaciones de Mujeres por la Revolución Cultural y Unidad (Alliance of Women’s Organizations for Cultural Revolution and Unity, which represents 17 parent organizations of indigenous and campesino women) to collectively draft a legislative agenda that benefits women. Most notably, the political participation of indigenous women and their standing in political processes was much improved (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017) and moved up to parity.

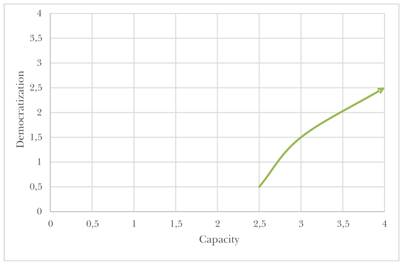

The graph below visualizes these changes in Bolivia, which are principally a steep increase in the capacity to channel the (intersectional) demands of women’s rights organizations. However, in terms of institutional capacity -despite some improvements in the strategic positioning of the new mechanisms- the Bolivian machinery remained weak.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Chile

Chile’s National Women’s Service (Servicio Nacional de la Mujer, SERNAM) was created in 1991 as part of the executive branch and played an important role in policy research, coordination, monitoring, and evaluation since then. It is arguably one of the strongest GEAs in the region in terms of capacity, funding and trajectory (Ríos Tobar, 2009; Fernos, 2010), so its position was already strong in comparison compared to the other cases. SERNAM was housed in the Ministry of Planning and Cooperation, but its director had ministerial status and therefore participated in cabinet meetings (Franceschet, 2005). Because of the ministerial status of the director, SERNAM could introduce legislative projects and was relatively successful in getting these approved (Haas 2011). Yet, as several observers have noted, the Ministerial status also made the SERNAMs’ agenda highly dependent on the ideological orientation of the ruling party (Baldez, 2001; Haas, 2011), and the personality and preferences of particular ministers (Haas, 2011). Its initial policy agenda in the 1990s largely reflected the agenda of the Christian Democrats and women’s movement organizations had limited influence on it (Baldez, 2001; Haas, 2011). Over time, the institution remained fairly stable, largely due to uninterrupted hold of the Concertación government which had been in power since the transition to democracy.

Between 1991 and 2000, SERNAMs’ budget doubled, and its staff and political influence increased (PNUD 2010, 161). After Michelle Bachelet came to power in 2006, SERNAMs’ power significantly expanded. The office received significant additional funding and was given access to interministerial negotiations for issues with important gender implications, such as pension and childcare reform. SERNAM coordinated a team of gender advisors, to monitor progress on the achievement of ministerial gender commitments within each ministry (Matamala, 2010). Another significant additional mechanism was the increased status of pre-existing Council of Ministers for Equality of Opportunities. by personally attending meetings of the Council and expecting other members of the Cabinet to do the same Bachelet advanced the gender equality agenda of her cabinet (Thomas, 2016; Staab, 2017;). Finally, SERNAMs’ influence and prestige were given a boost by the establishment of a Ministry of Women and Gender Equality under Bachelet’s second term in 2016, which is immediately after the period of study here (Thomas, 2016). These factors increased the institutional capacity of gender equality mechanisms to intervene in the political process. As part of a broader electoral reform, Bachelet introduced gender quota for the legislative in 2015. In 2018, so after the period of study, Chilean legislators established a women’s issue caucus.

As to its democratic quality, SERNAM and capacity to channel feminist demands, progress was less clear cut. According to Franceschet (2010), SERNAMs institutional design allowed it to act as a crucial “insider” ally to advocacy groups. Yet, relationships between SERNAM and Chilean women’s organizations were not very close and the level of cooperation was low. While Bachelet’s gender equality agenda was positively received by women’s rights organizations, no new institutional mechanisms for participation or inclusion were created. Also, the SERNAM so far has not developed a more intersectional perspective, paying attention to ethnic and sexual differences. While some agreements with indigenous organizations were made in 2018 - so after the period under study here- there was no structural representation of their interests (Gigena and De Cea, 2018). On the positive side, in her second period as president, Bachelet, appointed a SERNAM minister with a clear feminist profile and activist background.

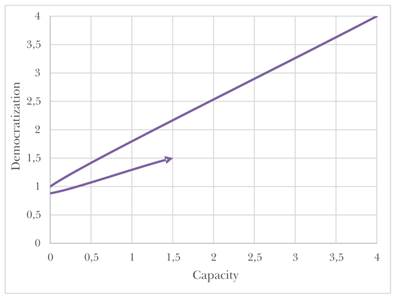

The graph visualizes the development of SERNAM’s institutional capacity and capacity to channel feminist demands between 2005 and 2015. In this period, there was an increase in both dimensions. Yet, compared to SERNAM’s institutional capacity, its capacity to channel feminist demands was much lower and did not significantly improve.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Ecuador

The National Council of Women (CONAMU) that was created in 1997 as part of the executive branch for many years served as an important and powerful link between the executive and the Ecuadorian women’s movement (Ugalde Vega, 2003; Lind, 2005). CONAMUs leadership had clear links to the women’s movement and its board of directors included three representatives of national women’s organizations. Yet, although CONAMU had an office for indigenous affairs, it did not establish a truly collaborative relationship with indigenous women organizations (Radcliffe, 2013). It established close ties to women in the legislative, but the representation of women in the National Assembly was low. In 2009 the Correa government abolished the Council with the promise to create a new National Council for Gender Equality (Lind, 2012). This promise was, however, not kept until July 2014, when the National Assembly finally passed authorizing legislation. Yet the new Councils only started to function after the end of Correa’s rule in May 2017, so beyond the period under study here, when the representatives from civil society organizations were finally elected to the different Councils, a condition necessary for the Councils to operate (Rousseau and Ewig, 2017). In the period between (2009-2014) a so-called Transitional Committee (Comisión de Transición) was established with virtually no power and resources. It operated largely at the fringes of the state bureaucracy.

Also, the strong existing link with national women’s organizations was discontinued. The new National Council for Gender Equality created in May 2014 had a very weak institutional capacity. It lacked a clear mandate to lead and coordinate the design and implementation of gender equality policies at the national and local levels and made no specific mandate for over-seeing and monitoring gender mainstreaming attributed to any institution within the executive branch. The percentage of the official budget allocated for the implementation of gender equality policies was reduced even further. Compared to CONAMU the new Council lacked the ability to closely coordinate efforts with feminist actors. No accountability mechanisms were established to monitor and assess the implementation of policies to promote and protect women’s rights. In addition, no mechanisms were put in place to ensure systematic participation of women’s organizations in the processes of the National Council or any other decision-making processes at the national and local level.2

The developments in Ecuador show a tendency opposite to the pink tide agenda with both a strong decline in the capacity of the state to intervene in gender relations and create effective gender equality policies and a steep decline in the access of civil society organizations to the women’s policy agency.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Comparison

Comparing the changes in gender equality policy agencies during the pink tide, we see heterogenous developments across the four countries (graph 5). The promises of more participatory political processes and inclusion of civil society actors in policy processes were certainly not fulfilled in relation to gender equality policies in three of the four countries. Some substantial improvement in both institutional capacity and capacity to channel women’s movement demands occurred in Chile under the leadership of Bachelet. While Chile’s SERNAM was already among the strongest GEAs in the region, Bachelet used her executive power in the agency to advance a prominent gender equality agenda and improve SERNAM’s position although the most substantive change in its institutional capacity occurred after the period under study. SERNAM advanced an agenda closer in line to feminist demands under Bachelet, yet the access of women’s rights organizations to policy processes was not substantially improved. Bolivia made significant steps on this second dimension, giving civil society a more prominent role and position in deciding upon the content and direction of gender equality policies. However, this was not backed by a reinforcement of the institutional capacity of the agencies responsible for designing and executing gender equality policies. The existing infrastructure remained a toothless tiger that voiced radical rhetoric without having the necessary power and competence to translate this into concrete policy measures or legislative change.

Remarkably, the women’s policy agencies in both Argentina and Ecuador were considerably undermined by the new left-wing governments. The Correa government eliminated the well-functioning CONAMU that held relatively good ties with women’s organizations and replaced it with a “transition” institute that functioned without mandate and budget for five years. It was finally replaced by the institutionally weak National Council for Gender Equality created in May 2014. Argentina’s CNM lost institutional capacity as it was repositioned within the state bureaucracy and experienced budget cuts. Substantive improvement in its capacity and relation to women’s rights organizations happened after the period under study here. The variation in developments across the four cases (graph 5) confirms the findings of Rodríguez Gustá, Madera and Caminotti (2017), who found no linear association between pink tide governments and strengthening of gender machineries.

The type of left party appears to explain some of the variations. The dispersed political authority seems to be positively related to a strengthening of gender equality agencies as the cases of Bolivia and Chile suggest, whereas parties with concentrated authority in Argentina and Ecuador did not lead to stronger institutions. Yet, contrary to my expectation that the new movement parties in Bolivia and Ecuador would create more access and new participatory mechanisms for women’s rights organizations, I only found this to be the case in Bolivia. Instead, in Ecuador the good working relations between state and women’s movements were disrupted under the Correa administration. This may be related to the ambiguous personal politics of president Correa, who despite labeling himself a feminist was also a vocal opponent to gender theory and blocked efforts to liberalize abortion. The concentrated authority model gave him veto power to block elements of the feminist agenda. In contrast, the MAS government opened new windows of opportunity for indigenous women to get voice and access that were absent before, yet at the same time, this significant step was not accompanied by resources and improved institutional capacity to truly translate feminist demands to strong policies and institutions. The Argentinean populist machine created limited openings to women’s rights organizations and firmly operated along partisan lines. Christina Kirchner gave only limited priority to gender equality issues. While political leadership appears to be crucial for the fate of gender equality agencies, the gender of the executive does not play a role as the contrasting protagonism of Bachelet and Fernandez de Kirchner shows. Yet, in all four countries, presidents hold large powers over the course of gender equality agendas.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Conclusions

My analysis of the development of gender equality agencies under pink tide governments in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador shows the limited effects of the pink tide agenda on these agencies. This confirms the skepticism of many Latin American feminists who experienced throughout the wave of democratization in the 1980s and phases of consolidation that left-wing parties are no natural allies and that progress in gender equality strongly depends on feminist mobilizations both within and outside the state apparatus. Women’s policy agencies can be important hubs in linking women within and outside the state and channel demands within the political realm. Yet, their political leverage largely depends on a substantial institutional capacity to initiate, execute and monitor gender equality policies in all policy domains.

The cases make clear that the steps made by pink tide governments to both increase the capacity and democratic quality of these institutions were overall limited. In some cases, we even saw opposite developments that curbed the position of such agencies both institutionally and in their capacity to channel feminist demands. In short, the promises of new left governments did certainly not materialize in the field of gender equality policy institutions. The pink tide did not result in a higher degree of “state feminism” across the region and we may therefore expect that gender equality policy transformation remained very limited. Further investigation is necessary to structurally compare policy change across some key areas and determine whether women activists have possibly found other ways to influence the policy agenda of the new left governments in the absence of significant institutional infrastructures.

The improvements in capacity found in Chile and Bolivia offer only limited protection against eventual backsliding under more hostile governments, as the influence of the executive on the agencies is very large and has not decreased. The gender equality agencies have not become more accountable to their constituencies and have not established better mechanisms for consultation, to turn them into a strong tool for women’s rights organizations to advance and defend gender equality. This makes GEAs prone to ideological manipulation and cooptation, rather than capable to act more autonomously to defend women’s rights.