Introduction

Since Brazil's redemocratization process, which occurred during the consolidation of the Federal Constitution of 1988 (FC88), we have observed the emergence of a social and political context in which citizen participation has become a key strategy in spaces of political action in Brazil's democracy. In this context, a closer relationship between the State and society has also been observed, in which, as a social achievement, the public administration is more permeable when it comes to popular participation.

This democracy with more participative features that promotes civil associationism held a privileged space within local governments throughout the 1990s. One example is the Participative Budget (Abers, 1998; Santos, 2003), but it also made its way into the federal sphere after the Political Pact established during the first term of president Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula (Labor Party - PT). During this time, new participative institutions were created: for instance, the councils and national conferences1 that were granted institutional legitimacy with decree Nº 8.2432 (during Dilma Rousseff's term), which established the National Policy of Social Participation (NPSP) and the National System of Social Participation (NSSP).

The increased presence of militant union members and social movements within the State's structure expanded formal and informal access to institutions and also improved these movements' chances of success, to significant institutional and legal impact. In this way, a new State-reformist paradigm is observed, a paradigm that Santos (1999) calls newest-social-movement-State3. This paradigm posits a rearticulation of State and society, combining representative democracy with participative democracy. With this scenario, the State's reformation began to be viewed not only as an administrative and managerial matter, but also as a political project (Santos, 2019).

The Brazilian State's condition of «newest-social-movement» was identified, during what was considered to be the most progressive period of government (2003 to 2016), on two fronts: 1. civil society leaderships' (social movements, unions, intellectuals, etc.) great adherence to direct or indirect management of the State4; and 2. increased participation space for society in the formulation and implementation of public policy (Santos and Carneiro, 2016).

However, the newest-social-movement-State's incidence involved a situation that generated many questions within popular organization. Despite the progress when it came to better conditions for dialogue and the achievement of policies with a more emancipatory perspective, such as the solidarity economy ones, there was debate, both in politics and academia, about a constant risk that permeated this closer relationship between State and society: a possible co-optation of social movements by the State.

The current Brazilian political context, even when considering a brief period of time, is very different. Starting in 2018, Michel Temer's (2016 to 2018) and Jair Bolsonaro's (2019 - present) administrations gradually eliminated participative processes in public policy management and went back to a more conservative and authoritarian kind of public administration. This premise is found in decree Nº 9.7595, from April 11, 2019, which revoked decree Nº 8.243 and also eliminated and established guidelines, rules, and limitations for federal public administration collegiates.

These conditions alter significantly the political arena of social movements, which were long accustomed to a more relational political action with the State, and that, in light of the current context, need to rethink and reorganize their resistance against capitalist, colonialist, and patriarchal forms of oppression and, consequently, need to organize an opposition and the conditions to fight the State.

Thus, reflecting about and understanding social movements through the lens of autonomy is even more necessary. If the issue of autonomy was important before, with the risk of co-optation, now it is necessary in the face of an emerging form of political action that confronts violence, including even the State's offensives. With this in mind, the goal of this article is to talk about autonomy as various different possibilities, based on the experience of the Brazilian Solidarity Economy Movement (BSEM) in its recent relations with the Brazilian State.

In order to achieve this goal, this work combines two studies6 coordinated by the authors, which were carried out within the BSEM framework and seek to understand the movement based on its political organization and its relationship with the State and other movements. These studies have a qualitative character and are linked by a methodological and epistemological proposal approached as militant research7. In this form of research, the researcher is understood to be "one who participates and shares the social and political project of their field of study" (Cunha and Santos, 2010: 15). This involves partial results of a literature review, documental and empirical research as well as conducting semi-structured interviews and participative observation, making it a scientific article based on an empirical case.

In addition to this introduction and the final remarks, the text is organized as follows: first, a presentation of schemes to interpret autonomy as a key to understanding the actions of movements in different political contexts; a section contextualizing the BSEM experience, detailing its challenges; and, finally, a section reflecting on the BSEM based on the different possibilities of autonomous action.

Autonomy as a key to analyze the actions of social movements in dynamic political contexts

The many possibilities of autonomous action

First of all, it is important to note what is understood here as the autonomy of social movements8. Therefore, it is worth our while to take a look at the farthest-reaching definitions of the idea of autonomy, albeit in a synthetic manner, and even if it is not a specific objective of this work; these definitions go beyond our more original interpretations, which are described later on in this work. In this way, Gustavo Oliveira and Massimo Modonesi (in print), for instance, performed a mapping of theoretical appearances of Latin American autonomies in the last 20 / 30 years. They found that autonomy can appear as rejection, independence, counter-power (and popular power), emancipation and community (and Good Living).

In this context, it is especially relevant to explore a definition that, as part of our analysis, traverses the five approaches mentioned above and that emphasizes a radically egalitarian form of the exercise of power, meaning a form that is radically opposed to the one practiced by the State and its colonial-capitalist rationality (Marañón, 2017). Aware of the risk of being excessively synthetical, we opt for Gilberto López y Rivas's definition, which posits that autonomy means "to be governed by one's own rules and power, opposed in consequence to all heteronomous dependence or subordination, would be the most widespread definition, regardless of the subjects who put it into practice" (2020: 81). Although the author's definition encompasses a wide variety of subjects, as he himself puts it, it is no small matter that the conversation regarding autonomies in Latin America grew exponentially as a result of the anti-neoliberal movements of the 1990s and 2000s. As part of this context, it is worth highlighting the Zapatista movement in Mexico, in 1994 -which served as a catalyst for countless other indigenous movements- as well as the uprisings of December 19-20, 2001, in Buenos Aires and its environs (the Piqueteros, neighborhood assemblies, businesses occupied and recovered).

As we can see, not all approaches to autonomy -and, in turn, autonomous actions or practices- focus on its relational character, meaning that which concerns itself both with autonomy and with the "other" that autonomy interacts with. Emancipatory or communal approaches, for example, focus more on their own constructive and constitutive characteristics than on their relationships with other subjects or institutions. In this way, it is worth highlighting that this work is embedded within the context of conversations about autonomy as independence, in which autonomy's "category pair" is the State. In other words, the way that the BSEM will become more or less independent, or more or less dependent, is through its relationship with the State.

In these terms, as well as in previous studies on the subject, autonomy is defined as the collective, lucid, and reflective capacity (Castoriadis, 2013) to, first, reject a part of the State or to reject it entirely, and, later, to build an alternative for that rejection. Therefore, autonomy is understood as a double relational process of rejection-construction, as a concrete, superimposed, and combined approach to autonomy as rejection, and also as emancipation, as we noted above in the theoretic approach. If Castoriadis's (2013) imagined society (or, in potentially more didactic terms: emancipated society) is still a project, the movements' capacity to reject injustices that have been legitimized by the State-form and to create alternatives to the space they rejected is a strategy of anticipation today for the imagined society of the future. This paragraph articulates, broadly speaking, the theoretical-analytical argument that is the guiding thread of this study.

In order to reinforce the notion of autonomy as a properly relational category, it is necessary to consider that a movement or experience can only be declared autonomous as long as there is a relationship with an "other." Basically, it is when a movement or experience is self-determined, self-organized, and self-governed in relation to an institution or an individual or collective subject that could, in theory, impose on it a way of functioning.

The very category of autonomy challenges us to think about it in a different way, since, whether or not we see it as a preview of the autonomous society of the future (Castoriadis, 2013; Oliveira and Dowbor, 2020), it represents merely localized experiences in intense interactions of conflict, mainly, with the capitalist system, with colonialism, with the patriarchy, and with the nation States that they are a part of. In this context, the process of autonomy is a process of infinite forms of action that occur in the movements' day-to-day.

We also need to emphasize that it is not possible to think about autonomy as a category that explains what a certain social movement is. Movements are fluid and oftentimes unpredictable, since they are affected by countless different social dynamics. In the words of a renowned Brazilian researcher of these movements: "There will never be a completely finished and definite theory about them. This is a characteristic of the object of study itself" (Gohn, 1997: 343). That is, we are not proposing to think of autonomy as a totalizing key to explain social movements, which, in this case, would be autonomous above all else. It is important to stress this matter concerning the arguments that frequently point to the end of autonomy when it is co-opted by another subject, in our case, the State. The analysis that sees an automatic cause-and-effect process between autonomy and co-optation is simplistic (Zibechi, 2007). For this reason, we consider autonomy to be a frame of action for movements -whether it is in the form of conflict or cooperation with the State (Santos, 2019), or in the form of developing self-governing practices and policies (Baschet, 2017)-. Therefore, this means thinking of autonomy as action located at a specific place and time (Holloway, 2011).

Keeping in mind the reflections presented up to this point, we now present the typology that is used as a reference to understand the different types of autonomy in a scheme of analysis that combines autonomy with State-movements relations:

(i) Rejecting the State in its entirety leads to constructing ways of life in its margins;

(ii) Rejecting the State's ways of functioning leads to constructing alternative forms of organization and political conflict outside of institutions;

(iii) Rejecting the historical inequality of the State's decisions leads to producing public policies and constructing alternative proposals to such policies (Oliveira y Dowbor, 2020: 3)

Putting it briefly, in the first type, the movements reject the State in its entirety and, as a result, create other ways of living based on how essentially different they are from the State and how differently they see the world. In this case, even when there are opportunities for movements to access (participate in) the State, autonomy means a set of actions at its margins, meaning the absence of direct interaction. In the second type, movements reject the State's power and hierarchical functioning and, as a result, create alternative forms of organization and political conflict outside of institutions that achieve more or less pressure, recognition, and inclusion of issues in the State's agenda. Finally, in the third type, movements reject the historical inequality in the State's decision-making process that remove these decisions from the movement's worldview, and, as a result, create public policies and practices/dynamics that aim to produce new institutional mindsets within the State itself.

Graphic 1, seen below, indicates that an experience may move up or down on the vertical variable (autonomy), according to having more or less of the relational process of rejection-construction. For such an experience, however, to be considered interdependent autonomy, embedded autonomy, or independent autonomy, it will also depend on the political context and the possibility of State-movements relations to unfold as institutional participation, as can be seen in the subsection that follows.

Political context and State-movements relations

State-movements relations as institutional participation are twofold. On one hand, participation occurs in both general and specific contexts, in an intertwined way, and not as a permanent or endogenous version of the State-form. At this point, it is important to highlight that the possibility of participation emerges as a political opportunity that a movement may or may not use as a form of institutional action (Dowbor, 2012). When this action is carried out, it is only one form of action within a wider range of a determined repertoire. On the other hand, considering a favorable political context that leads to some sort of participative or "porous" State, movements could autonomously opt for non-participation.

At this stage, it is important to keep two things in mind: 1. certain political contexts present more (or fewer) possibilities of institutional participation than others, with horizons being a total impossibility of participation ("Dependency" quadrant in Graphic 1), the possibility of participation as an interdependent autonomy or embedded autonomy (interdependent autonomy and embedded autonomy quadrants in Graphic 1); and finally, 2. even in contexts where participation is highly likely, movements could opt for actions outside of institutions that may or may not be conflictive (independent autonomy quadrant in Graphic 1). In this case, there is a State-movements relationship, but it is an extra-institutional one that may unfold in a direct or indirect manner. Considering the typology for each form of autonomy, mentioned above, types one and two may be located at some point within the interdependent autonomy quadrant, while type three may be at some point between interdependent autonomy and embedded autonomy.

To determine whether a political context leads to more or fewer possibilities of participation, we need to consider various conditions. First, it is necessary to look at each administration's political project9 during each period under analysis (Dagnino, Olvera and Panfichi, 2006). Secondly, it is necessary to reflect upon the arguments that characterize the types of management10 in the context of Latin American governments (Bringel and Falero, 2016).

It is also important to think in terms of macroeconomic association11 (Boito Jr. and Berringer, 2013) in the center-periphery relationship of the capitalist-colonial-patriarchal world-system (Wallerstein, 2008).

The Solidarity Economy Movement in Brazil: context and current challenges Methological aspects

As already exposed in the introduction, the discussions presented here are framed within the methodological scope of a comprehensive-interpretative approach; in our case such scope was carried out from militant research (Cunha y Santos, 2010; Fals Borda, 2009; Russell, 2015). The character of our militant research -as well as the choice of the case- is explained, as already mentioned, because both authors are part of BSEM as researchers and militants. The purpose of highlight this dual character is important since as researchers we are fully aware of neither generate biases in the inner organization of the movement nor in the rigor of the scientific work.

The Brazilian Solidarity Economy Movement (BSEM) has always been a political space where people with the most divergent visions and strategies coexist. Therefore, it is characterized as a heterogeneous space of political action where a significant variety of groups converge and recognize each other in the perspective of another economy project based on collective organization, political participation, self-management, solidarity, respect for nature, centering work's role in life (Coraggio, 1998; Santos, 2010). For a long time, this movement was understood based on a collective subject that responded as a privileged interlocutor: the Brazilian Solidarity Economy Forum (BSEF) which was born in 2003.

However, the current situation changed over time, not only in the State arena, as was mentioned in this article's introduction, but also in civil society. In terms of the BSEM, which emerged in the early 1990s as a political organization, about 10 years before BSEF, these changes consist of the recognition of other active subjects in this process, not just the BSEF. In this way, it is important to understand the popularity of the political movement that represents Brazil's many other economies, keeping in mind the new configurations it adopts -especially starting in 2016, when there was a break in the relationship between these movements and the State-.

It is in this context and historical framework that many collective subjects reaffirm themselves while others emerge and join the BSEM; even though at that time not all of them assume the BSEF as a legitimate representative. At the national-level, we are talking at least about Support and Promotion Entities; Network of Public Policy Managers for Solidarity Economy; Entities for the Representation of Solidarity Economy Enterprises; Quilombola and Indigenous women and men; Feminist Economy Network; Network of Community Banks and Currencies; Brazilian Network of Responsible Consumption Groups; Network of Technological Incubators of Popular Cooperatives, the latter driven by academics; National Agroecology Articulation; National Movement of Recyclable Material Collectors; Youth and Solidarity Economy Network; etc.

These views on the process are justified, given that, currently, there is a significantly larger number of solidarity economy experiences, and also other types of economy that do not necessarily identify with that forum's vision and, therefore, engage in other forms of political organization. In addition, the BSEF has experienced significant changes in its organization after the 2016 period, when Brazil's political scene changed. Considering this complexity, for the scope of this work, we used the following research techniques:

a) literature review, to deepen the research themes;

b) Participant observation in meetings (working groups, commissions, management committees), seminars, internal events of BSEM, and dialogues between the movement and the State from 2016 to 2020;

c) Semi-structured interviews with BSEM subjects (12 interviews) and with State agents linked to solidarity economy policies (4 interviews). The choice of interviewees was based on their protagonism in the movement; taking care to consider representatives from the most diverse regions of the country has been important;

d) Documentary analysis of dissemination materials, bulletins, reports, studies, technical and informative notes, and other documents and publications produced by BSEM or the State, in this case regarding solidarity economy policies.

Below, we provide some context for these two processes.

Changes in the political movement of other economies

After 2003, Brazil witnessed an advancement of the initiatives considered to be a part of the solidarity economy in favor of a nationwide organized movement that sought to consolidate space for the many different expressions of counter-hegemonic economies. It was in this context that the Brazilian Solidarity Economy Forum (BSEF) first emerged. The BSEF was born from the National Solidarity Economy Plenary Sessions (NSEPS) organized by the Brazilian Solidarity Economy Working Group.

This Working Group emerged as a result of an organization and articulation process during the first World Social Forum (WSF). It was made up of 12 organizations and solidarity economy networks, and it was structured throughout a period of two and a half years (from 2001 to 2003). In their commitment to the emancipatory character of the movement, Working Group representatives encouraged regional/state pro-forum debates in order to inspire commitment in everyone involved in the matter, especially workers. This process of debate and organization led to the birth of the NSEPS. The first NSEPS was held in December 2002 in São Paulo, with around 200 participants; the second NSEPS was in Porto Alegre during the 2003 WSF, with 800 participants; the third NSEPS was in late June 2003 in Brasilia, with 830 participants; the fourth NSEPS took place in March 2008 in Luisiânia, with approximately 400 participants; and the fifth NSEPS was held in December 2012 in Brasília, with approximately 600 participants.

Among other topics, the plenary sessions discussed pending issues in the context of Lula's and Dilma's administrations as well as the BSEF's formation and political organization. This is where Brazil's legitimate solidarity economy movement first emerged. After these plenary sessions, a commission was formed, responsible for negotiating the insertion of public solidarity economy policies in Lula's government platform; also as a result of this conversation, the National Solidarity Economy Secretariat (NSES) was formed, led by professor Paul Singer (undoubtedly one of the most renowned researchers of this topic in the country).

Another important fact that resulted from this movement was the first "Encontro de Empreendedores", held in mid-2004 in Brasília, where it was agreed that the BSEF was not merely an organization made up of agents that supported the solidarity economy, but rather a space where the public sector came together with public power and the third sector, resulting in a consolidated movement with different categories. At this event, solidarity empreendedores were evidently the protagonists, showing how they became national leaders and political subjects based on an affirmative forum.

Considering what we have discussed so far, reflections on the solidarity economy seem to transcend the socioeconomic process of the empreendimentos' day-to-day, emerging as a construction linked to a larger plane that seeks to legitimize a political space in today's society. Thus, BSEF's construction as a political subject led to new developments that allowed for innovative reflection both in the theoretical and the empirical field. The BSEF is a new organization, historically speaking; in previous studies, we sought to understand its origins, management, possibilities, and political potential -the movement itself-.

It is very symbolic for solidarity economy subjects, as well as frequently mentioned in its documents12, that the BSEF's creation and the elaboration of a Letter of Principles and of a Solidarity Economy Platform materialized in the third NSEPS, in June 2003, around the same time that the NSES was officially implemented at the heart of the Ministry of Labor and Employment (MLE). In this way, it is possible to say that the birth of the solidarity economy at the national level occurred in the State and in civil society at the same historical moment through interlinked processes.

Since its creation, the BSEF and its member-entities enjoyed a role as privileged interlocutors at the NSES -at least during Lula's first term- when it came to demanding, proposing, executing, and monitoring actions and public policies. The BSEF was often questioned regarding this role in relation to the State and its composition and management structure (very contentious issues at the fourth National Plenary Session in 2008), although it is hard to deny that it has obtained the leading position as the main national solidarity economy network in Brazil.

When defining and describing the solidarity economy movement, it was always taken into account that the BSEF is not the be-all and end-all of Brazil's solidarity economy. The latter is much broader and includes subjects who do not identify with this Forum. However, in recent years, this diversity has increased significantly, not only in terms of economic organization forms, but also in terms of collective and representative organization. For this reason, we choose to see this movement as a political movement of other economies, recognizing the movement based on the solidarity economy, while also broadening perspectives in order to study the forms of political organization of the different subjects that make up the universe of other economies13. By other economies we mean the economic initiatives that oppose the hegemonic concept of economy and use survival strategies practices to bring to the economical scene political elements characterized by solidarity, collectivity, sustainability, trust, and emancipation, among others. From this, a significant diversity of economic activities considered counter-hegemonic arise (solidarity economy, indigenous economy, feminist economy, peasant economy, economy of the common, popular economy, etc.) that make up the universe of other economies (Santos, 2019).

Changes in the Brazilian political context

President Dilma Rousseff's (PT) second term adopted a stance that was closely related to the neoliberal offensive. The electoral process that reelected Dilma was a very tight race, and the president only emerged victorious after she made a commitment to focus the government's attention on the demands of social movements (who played a key role in the reelection), to the detriment of the dominant system's economic growth logic. However, this did not happen. After the campaign, the president began to adopt economic measures that she had promised she would not, such as changing labor laws and increasing taxes. Instead of honoring her commitment to youth, women's, black, and rural/urban workers' movements, all of which supported the government in the campaign, Dilma presented names for ministerial composition that favored economic policies more than social ones (for example, Kátia Abreu, the main leader of agribusiness Brazil and enemy of the rural movement, nominated as head of the Ministry of Agriculture). She also limited the space for emancipatory policies, merging the offices for women, youth, human rights, and race into a single ministry.

In addition to upsetting social movements and leftist sectors, Dilma also made things uncomfortable for allied parties when she rearranged the ministries. The government base parties claimed that they were not contemplated as they would have liked in the distribution of high-ranking posts. This generated an even bigger crisis in the public machine because these went on to join forces and an extensive coalition (even with a significant adherence to common sense produced by the media and by more conservative groups of society) against PT, which, later on, led to an impeachment and the removal of the president from office. This process was possible only with the complicity of the judiciary branch, server of the interests of the ruling class, which created the conditions for the removal of the president, once it promoted a judgment much more political than technical, providing evidence of abuses to the Federal Constitution of `88, as seen in the display, on national television, of an illegal clip, in order to encourage the tacit and public condemnation of president Dilma. In this case, we can State that the dispersion mechanisms enabled by the law in order to mediate the capitalist State's power relations and which were pointed out by Santos in the Negative State Dialectic (1982) now take on a new appearance (one that deserves to be studied future analyses), but what still stands out is the starring role played by the law in the capitalist State's revitalization.

This brief historical review allows us to comprehend structural differences that precede the timeline of the PT's actions over the last few years. There were some very important and recognized steps forward. However, expectations surrounding the highly anticipated reforms (tax, political, agrarian, etc.) were higher, even when it came to the State's democratization. The complexity in comprehending the reasons for the processes that occur in this story lies in the political capacity to attend various matrices that unfold in a wide variety of organized interests in all sectors of Brazilian society that reflect directly on the interests of the different political forces that made up the government. In this sense, the PT made an effort to address these different interests, but it did nothing to compromise the project to accelerate Brazilian capitalism.

The PT's choices with regard to the contradictions of the heterogeneous State (Dagnino, Olvera and Panfichi, 2006) were naive and created the conditions for the removal of president Dilma. According to Santos (2016), such choices reflect a significative number of misconceptions:

[...] once in power, the PT decided to rule in an old-fashioned manner (that is, through oligarchy) with new and innovative goals. Ignorant of the lessons left behind by the Weimar Republic, they believed that any «irregularities» they committed would be treated with the same benevolence as the irregularities of the elite and conservative political classes that had dominated the country since it became independent. Ignorant of the Marxist lessons they claimed to have learned, they did not understand that capital trusts only its own to govern and that it is never grateful to those who are not its own yet do it favors. Taking advantage of an international context of great appreciation for primary products, caused by China's development, it encouraged the rich to become richer as a way to guarantee that it would have the necessary resources to carry out the extraordinary social redistribution politics that made Brazil a substantially less unjust country by freeing more than 45 million

Brazilians from poverty's endemic yoke. As the favorable international context comes to an end, only a «new-style» politics could sustain the social redistribution, that is, a politics that, among many other aspects, would be based on the political reform to neutralize the promiscuity between political power and economic power, on the reform to tax rich people in order to finance the social redistribution after the end of the commodities boom, and on the media reform, not to censor, but to ensure the diversity of published opinions. However, it was too late to accomplish so many things that could only be done on their own time and not during a crisis (Santos, 2016).

Given the circumstances, Michel Temer began his term in office based on a perverse agenda against the poor, workers, minorities, and public assets, as is expressed on the program called "Ponte para o futuro". It is a neoliberal proposal similar to the one in Europe and that had been losing the race against the popular vote in the elections that preceded this administration, although previous administrations had already shown strong signs of implementing it. Either way, it is a governmental logic that attacks labor victories and social policies in particular, while also limiting the space for the emancipatory policies, the solidarity economy ones, for instance.

Subsequently, in 2018, Jair Bolsonaro was elected, and with him a project even more conservative and offensive to social policies and human rights. The new administration would go on to end a significant number of social policies, relegating them to a more peripheral and assistance-based status. In this context, solidarity economy policies are downgraded and sent to a department within the Ministry of Citizenship that is managed by people without political recognition in the universe of other economies.

Considering that the BSEF initially emerged as a political interlocutor and that it had at its disposal public resources not just to support its causes, which became NSES programs, but also for the movement's political formation and organization, we can see, in a certain way, the dismantling of a State that is more attentive to the matters of social movements has a significant impact on civil society. It is important to understand these conditions when it comes to the political dynamics (progress and limits) of the solidarity economy within the federal government, especially, because they influence the social movements' organization designs and the construction of resistance against the dominant logic.

The changing political contexts and autonomous actions of the Brazilian Solidarity Economy Movement

It is within the context presented above that the BSEF became fragile, and other political forces in the movement, especially the ones linked to unions, such as the National Union of Solidary Cooperativist Organizations (UNICOPAS), went on to become the protagonists and principal interlocutors. With this in mind, the BSEF, alongside other solidarity economy subjects, is organizing the sixth NSEPS, the mobilization for which began in 2019 and is supposed to end in 2022. In this way, it becomes important to comprehend the protagonism of this movement in a historical moment in which it is articulating the resistance and rethinking its political organization.

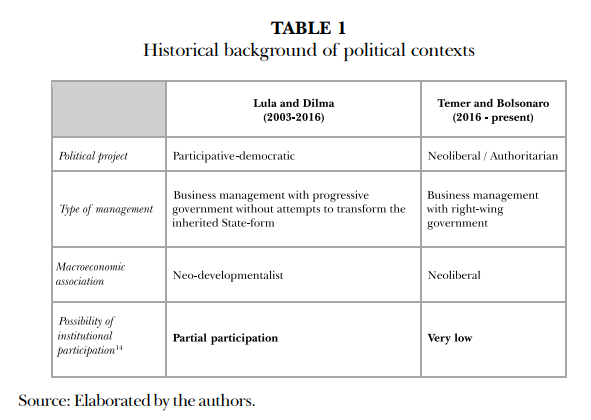

The BSEM's experience takes place within the social whole. Therefore, it exists in an intense interaction with the political context; it also produces a determined context. This observation helps avoid misconceptions that deny in any way the link between action and context: the action happens within the context and, therefore, it has an impact on its continuity or breaks, which, in turn, will also have an impact on the movement's future actions. The description and analysis in this section look at the context backgrounds as presented on Table 1, on one hand, and on Graphic 1, on the other.

Considering the factors for the different political contexts, as presented in the "Political context and State-movements relations" subsection (notes 12, 13 and 14), and the contextual description in the section immediately before this one, we can assert that the political context of both PT administrations (Lula and Dilma) was a context that combined a participative-democratic political project, a business type of management with a progressive government without attempts to transform the inherited State-form, and neo-developmentalist macroeconomic association. It is necessary to highlight that, particularly with the last variable in mind, almost at the same time that Lula handed over the presidency to Dilma the world economy was in a deep recession. This meant, among other things, the previously mentioned end of the commodities boom that, consequently, brought Dilma's macroeconomic policies to the border between neo-developmentalists and neoliberals. It is important to highlight this situation because this movement also represented the beginning of a troubled period in Brazil's politics and economy that would lead to the 2016 Coup.

The possibility to participate in Lula's and Dilma's administrations was the «partial participation» kind, meaning that the social movements that understood that participation was a strategy that they could use found opportunities to do so. It is worth mentioning, though, that this "opportunity to participate" was seen by some authors as a form of currency, given the need to "soften" in a way the social movements' critiques of the government. For example, Mauro Iasi (2012), called this process the silencing of the working class. Ana Claudia Teixeira (2013), in turn, found that the State's openness to participation during the PT administrations started out promising to be provide an opportunity for a true social transformation, but it ended up being, however, no more than a space for the government to listen, without any real progress regarding the movement's demands.

In this context, it is necessary to point out that this silencing, to borrow Iasi's term, at least in the BSEM's case, did not mean co-optation, as Lúcia says in an interview15:

I always say that it is not a matter of co-optation -it never has been- of any movement: "oh, the State co-opted the movements!"

No, the movements discussed that relationship and decided…they were aware of the risks, they were aware of the issues, they asked questions, and, despite that, they decided to have a closer relationship with the State (2020).

From the point of view of the autonomies, going back to Graphic 1, it is necessary to note the difference between interdependent autonomy and embedded autonomy. Three aspects are important: 1. both have a direct and explicit relationship with the State; however, 2. the intensity of the movement's twofold process of rejection-construction in relation to the State is different for each case; this means 3. conflictive interaction16 for embedded autonomy and passive interaction for the interdependent autonomy.

From 2003 to 2010, Lula's administrations, the BSEM's worldview was so aligned with the administration's political project that the movement entered the State, participated, and achieved some of its demands. However, it did not play a starring role in explicit conflicts of ideas; and if there are no opposing ideas or practices, there is no dialectic in the relationship under analysis. Autonomy and dialectics go hand in hand; therefore, it was a low-intensity period for the BSEM'S autonomy in relation to the State, per the terms used here.

In contrast to Dilma's presidency, in which the PT's political project remained, from the point of view of intentions, but was not consolidated in practical terms, in Lula's administrations, especially because the world's economy was going through a "good time" and Brazil was a part of it, the difference between intentions and action was pretty small. And so, the social, democratic and popular character that is a historical feature of the PT's political projects was aligned with the BSEM's identity when it came to intentions in both administrations (Lula and Dilma), but they diverged when it came to concrete actions in both periods. During Lula's administration, the BSEM's constructions based on the State-movement relationship were more or less agreed upon between the two subjects. Therefore, it was almost impossible to see anything related to the process of rejection-construction that is a characteristic of autonomy. In other words, the movement rejected little to nothing from the State and, because of it, its constructions did not originate in an intense process of rejection. Lula's presidency was a time during which the BSEM's autonomy was of the interdependent autonomy type. There was clarity and reflection in the movement's actions (as is clearly expressed in Lúcia's words, presented above), but this rarely showed itself as a rejection of the State or of any of its fractions or facets.

This first year of Dilma's administration would change the BSEM's autonomy, from interdependent to embedded autonomy. Two important events marked this shift in autonomy type because they produced intense conflicts of ideas that were responsible for the emergence of rejection as a precedent for the BSEM's constructions. In 2011, the first year of Dilma's administration, two State measures produced intense debate at the heart of the movement. The first one was when the executive branch sent the legislative branch Bill 865, dated March 31, 2011 (Bill 865)17, which would create the Special Microbusiness Secretariat; the latter would function as a sort of ministry and incorporate the NSES and the National Solidarity Economy Council (NSEC). According to interviewee Joaquim (2020, verbal information), who was part of the BSEF's executive secretariat, the BSEM responded with a form of mobilization that was a first in its history. The novelty lay, precisely, in the conflictive character, in terms of the ideas and evaluations about the institutional architecture and the solidarity economy's place within it, which was debuting in the State-BSEM relationship at the time.

Realizing the need to reject that State action, the movement mobilized a great deal of its bases and built, within the State itself, a form of collective action new to it. There were "twenty-three public hearings (in different States of the country), with over 2,500 attendees, dozens of federal and State representatives, micro and small business leaders, representatives from the federal government (NSES) and State governments [...]" (Bertucci, 2011). The rejection of State action as expressed in the mobilization against the approval of Bill 865 was effective, and the movement's constructions resulted in the NSES remaining within the structure of the Ministry of Labor and Employment. This is a textbook case of embedded autonomy because the movement rejected something in/from the State and built, based on institutional participation, ways to guarantee a consensus regarding what the BSEM saw as appropriate for its demands.

The second measure of Dilma's presidency, also in June 2011, that would generate unease in the State-BSEM relationship was the launching of the Brasil Sem Miséria (BSM) plan. BSM was a program that integrated many ministries in its actions and whose main objective was expanding the effects of the Programa Bolsa Família. It was a plan led by the Ministry of Social Development and Combate à Fome. The solidarity economy was part of BSM's action plan. It was precisely this what led to great differences (rejection) in the BSEM with regard to the plan. As Joaquim points out, discussions revolved around diverging ideas about the character of solidarity economy policies that would be a part of social assistance policies.

On one hand, the opinion of a considerable number of BSEM workers and activists who found that the solidarity economy, due to its liberating character and potential to reinvent the labor relationships rendered natural by the capitalist-colonial-patriarchal world-system, should not be confused for charitable social assistance actions; on the other hand, the Dilma administration, as well as some of the NSES's commissioned positions, who believed that the high budgetary contribution that would result from this integration could produce positive results for solidarity economy experiences and vulnerable sectors of the population. At this point, even with the twofold relational process of rejection-construction in evidence, the struggle to reach a consensus at the heart of the movement resulted in low mobilization, and the solidarity economy remained within the actions of BWP. Even so, this event can also be seen as embedded autonomy because, although the State measure prevailed, the BSEM rejected something in/from the State that it did not agree with and proposed its own alternative for actions to replace what it rejected. However, the lack of consensus and, in turn, of mobilization within the movement itself, reduced its chances of success.

The last period to be analyzed is the time between the Coup of 2016 and the present time (December 2020). In terms of political context, it is a period in which the political project is a clear mix of neoliberal and authoritarian projects, with a business-type management and a right-wing government, although at the border of selective authoritarianism and extended violence in the social fabric, and with a neoliberal macroeconomic association. This alignment of conditions in the political context indicates a very low possibility of institutional participation. Proof of this is Jair Bolsonaro's attempt to end the functioning of national councils that managed public policies, to which the NSEC belongs; and, specifically about the solidarity economy sector, it is important to point out the NSES's depreciation during Michel Temer's administration and its end during Bolsonaro's.

The State's evident rejection of participation, which began with Temer in 2016, produced a new wave of internal discussions in the movement about a wide range of issues, including discussions about the very reason for the existence of its main political subject, the BSEF. In a BSEF reunion during the Latin American Solidarity Economy Fair in Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, in July 2017, many workers and activists from across Brazil were of the opinion that the experience of intense State-BSEM relations, which started in 2003 and ended in 2016, had left them a few lessons. With a focus on critiques of the BSEM's financial dependence on the State, some of the remarks were striking: "We understand that we are coming from a time of dependence on public policy, and now we need to move forward with the idea of becoming self-sustainable", "we became spoiled because we trusted too much that we would always public policy money", "I think that we have always played a subaltern role in relation to the [institutional] policy -we need to revert this-", "could this be the right time to detach ourselves a little from this [institutional policy, political parties]?".

The BSEM's withdrawal from direct relations with the State, is, for the most part, a product of the political context post-2016 and could be interpreted as a return of sorts to an emancipatory historical horizon with regard to the capitalist-colonial-patriarchal world-system and, specifically, the State. Even before the meeting mentioned above, which took place between May and June 2016, when Dilma had just temporarily left her post due to the impeachment process that would lead to the Coup, two facts stood out: first, on May 11, soon after the president's temporary removal, Paul Singer and Roberto Marinho, his assistant secretary, asked to be dismissed from their positions at the NSES; afterwards, on the first days of June, the BSEF sent out a letter announcing its disapproval, that it did not recognize the new secretary, appointed by Temer, and that it would be unwilling to participate in dialogue with the new government (Santos, 2019).

From that moment on, what we could see in terms of public solidarity economy policies at the federal level was an ever greater dismantling. It is too early to say what the movement is constructing with regard to the place of explicit rejection articulated in the letter of repudiation. From the autonomies' perspective, we could go as far as to say that the present moment represents a return to independent autonomy18. With an open horizon, it is true that, as part of the mobilization and construction of the sixth NSEPS, the movement's restructuring concerns itself with the following topics19: resistance to capitalism's crisis; convergence with other social movements; the BSEF's organicity; and the relations with the State.

In order to make a summary of the period under analysis, it is worth noting that in the time of intense BSEM-NSES interactions -meaning, the PT administrations (2003-2016)- either in the period of interdependent autonomy or embedded autonomy, the State-movement relationship produced countless public policies that had been, for the most part, demanded by the BSEM, as Natália States (verbal information):

I think the NSES was very mindful of the guidelines agreed upon at the conferences; I think their policies were designed based on what was discussed at the conferences, especially the first conference. So, in this way, I am completely certain that all the government programs were put in motion according to the movement's causes. Therefore, there was, as you can see, the movement's strategy platform, there were two main documents, a statement of principles and a strategy platform (I can't remember its name), and in the platform were the movement's main causes. If you look at the political organization of the government programs, they correspond with those causes; in a way, they correspond with the guidelines that were discussed at the conferences (2020).

In more specific terms regarding public policies, along the axes of "credits for the solidarity economy and support for solidarity finances", "technical training and assistance", "commercialization and production and consumption networks", "solidarity economy's legal framework", "information and knowledge for the promotion of the solidarity economy", "the institutionalization of solidarity economy policies and social dialogue", "promotion of specific segments" (Cunha, 2012), there were more than 40 actions and policies in only the first eight years of the secretariat, during Lula's terms.

In an interview, João (2020, verbal information) notes three policy areas that he considered were successful. First, he highlights the Cataforte program, which focused on recycling cooperatives. Also, the Cooperation Networks program, which sought to promote productive activities, services, credit, commercialization, and consumption among the solidarity economy's-associated-collective working groups.

Lastly, João highlights the policies related to solidarity finances, which promoted everything from local experiments with social currency to the creation of community banks -Banco Palmas stands out- of which there were more than 1,000 in Brazil at the end of 2013 (Singer, 2014).

Around the time when the BSEM stepped back from interactions with the State, a period that we call "a return to independent autonomy" (from 2016 onwards), the question is: in terms of autonomies in the broadest sense, meaning the sense promoted by López y Rivas (2020), for example, what is the legacy left behind by the years of intense interactions between the State and the BSEM? As we look for a possible answer, it is important to point out that, although Paul Singer has tried to push forward his endo-development20 proposal, Paola (in an interview), whose views are shared by Leda (also in interview), seems to find that the BSEM's relationship with the State has, in some way, rendered the colonial-capitalist (Marañón, 2017) reasoning insurmountable at the heart of the movement itself, turning it into an obstacle for the strengthening of autonomy and self-management:

I think there's something linked to the present moment, a paradigmatic moment, let's say. We have a pyramidal way of structuring society, and, obviously, this reflects on political parties, unions, and social movements too. For me, the problem is that, no matter how much we defend self-management, we were not able to effectively come up with another structure, and this impacted the way the BSEF was organized. But I don't know if we could have done anything differently because, somehow, we mirror a structure that is part of society. A more horizontal structure, a structure that is more associated with self-management, etc. That structure doesn't exist that much in our society; it is still being born and there, obviously, it has an impact on the lives of people in various places (Paola, 2020, verbal information).

Although, strictly speaking, the endo-development proposal has not become effective as a public policy -which has consequently been a barrier, on the one hand, to overcoming the capitalist-colonial rationality within the BSEM and, on the other, to strengthening autonomy and self-management-, it is necessary to recognize that: 1. the solidarity economy policy in Brazil was a BSEM conquest that articulated the processes and meant guaranteeing the State's attention to the demands; 2. the relationship between the movement and the State was exhaustively discussed in the internal political organization, even when BSEM opted for collective action in dialogue with the State; 3. public policy, although peripheral in the budgetary sense, made a difference in the lives of the subjects of the solidarity economy; as a result, they began to have access to rights and dignity through programs and projects resulting from the public policy of solidarity economy in Brazil.

There have been mistakes and victories, progress and setbacks, but one thing is certain, and that is that the BSEM's experience, from its birth to the present time, calls our attention both economically and politically, as well as academically speaking.

Final remarks

From a theoretical perspective, this analysis sought to go beyond the appraisals that see the actions of movements that enter processes of intense relations with the State and the government as a loss of autonomy. If we understand autonomy, first of all, as a collective capacity for clarity and reflection about the necessary decision-making that the movements must face in their daily activities, this opens up an attractive field of study concerning autonomies. In other words, it could be fruitful, instead of abandoning the autonomy category and substituting it for others such as interdependence or even co-optation, to look at it in terms of its analytical potential as well as its potential to define abilities and strengths in the State-movements relationship. To continue with this theoretical discussion, it is worth noting that, in the context of emancipatory struggles within the capitalist-colonial-patriarchal world-system, it is this twofold relational process of rejection-construction that expresses the capacity of clarity and critical reflection that assume various shapes in determined political contexts.

For a critical, albeit synthetic, analysis of the BSEM's experience in the two periods studied in this chapter, we add some final remarks that are, obviously, not definitive nor seek to be hegemonic with regard to different assessments. For this critical assessment, it is important to point out that talking about the solidarity economy presupposes, at least within a diverse group of characteristics, thinking about self-management and thinking about it as a form of organization of associated-collective work. With this in mind, we can identify mistakes and possibilities in the historical process in which the BSEM was and still is involved.

For the first half of the first period under analysis, that of Lula's presidency, we find that the BSEM's almost nonexistent critical rejection regarding the State left the door open for a kind of adaptation or an "unintentional feeling of dependence". It is important to highlight that, in terms of actions that aim at a radically different society from the ones that make up the capitalist-colonial-patriarchal world-system, it would not be possible to relate with the State architecture and its functioning without an intense process of critical rejection. The absence of rejection could only produce continuities on the side of civil society, culture, and the reproduction of symbols, since more significant ruptures, of production and reproduction of autonomies, would require the construction of alternatives and rejection of the "State status quo". It was precisely the capacity and intentionality of critical rejection what took the second half of the first period under analysis into embedded-autonomy territory. In this second half, the rejection was evident, and this evidence is what allows for the politicization of the moment of construction, whether it is within the State or at its margins.

Finally, the second period under analysis opened the door for BSEM itself to discuss its tactics and even its strategic objectives. It also makes it possible to project that a context of extremely low possibilities of institutional participation points to at least two movements: a) that defining, explaining, and promoting self-management - understood as a way of organizing work- should be the movement's top priority; and that all the movement's actions as a collective subject, within the State or in its margins, should strive for this b) the BSEM opting for institutional participation as an action strategy is only explained by the possibility of using the State as a tool to build and strengthen experiences of self-managed associated-collective work; changes in the political context may result in the disruption of some policies -however, these changes are unable to take away the lessons about self-management learned by subjects of the solidarity economy-.

If a movement's objective is to reinvent certain types of social relationships, as is the case of the BSEM in terms of work, production, circulation, and consumption relationships, it can be powerful to think about interdependent and embedded autonomies simply as mean or paths -mostly hard to walk on- that take us to independent autonomy as a total rejection of the State and as the construction of forms of self-managed work and life in community.