Yearning for the comfort of an idyllic (and fastreceding) past is nothing new. In the late nineteenth century, the United States was still reeling from questions of self-identity posed by a devastating civil war, and the lure of an idyllic Antebellum time with clearly defined identities was seductive. During this period, images of domestic history intended for American audiences by George Henry Boughton (1833-1905), Edwin Austin Abbey (1852-1911), and Francis Davis (“Frank”) Millet (1848-1912) reflected a fascination with the past that moved beyond memory to fantasy. These images are also manifestations of longing for an imagined, particularly English past inextricable from a historically-related selfidentity. In their mature works, Millet and especially Abbey frequently dilate on English settings and subjects, while Boughton’s work represents the reverse: historical American subjects created in England. Boughton mythologizes Puritans in the same way that Abbey and Millet turn the English country narratives into archetypes. In all of these cases, the desire to recuperate an ever-attenuating past appears again and again.

This article will argue that England acted not just as a setting but also as a flexible temporal construct for artists like Boughton, Abbey, and Millet who were invested in recuperating a halcyon Anglo-American past, and that the familiar and domestic worlds created in their works reveal the palimpsestic nature of American identity in the transatlantic gilded age. While an anachronistic scene might be out of reach of personal memory, setting the scene in a recent past could place it within access of collective memory. By deformalizing the past, the artist renders that past moment more accessible to his intended audience.

Like a number of other American artists who relocated to England in the late nineteenth century (Woods-Puckett, 2016), these three men reenacted the tradition of transatlantic relocation to access the more robust art market and reliable patronage of the British Isles inaugurated by Benjamin West (1738-1820), John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), and Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) in the latter decades of the eighteenth century.

As cultural historian Elisa Tamarkin argues in her book on the subject of American Anglophilia, Britain was “imagined always as a reliquary of tradition, ornament, and ritual” (2008, p. xxviii). Indeed, the English past has been a continual source of myth, cherished by both British and American constituencies, and England was an inescapable part of American culture in the late nineteenth century. England was, after all, the country of origin for a large number of North America’s first immigrants and governed the colonies for over 150 years. The United States of America would not exist in its current form without its colonial English heritage. Much of what it is, how it functions, and its values (inasmuch as any nation can be said to have a set of shared values) turn on this inescapable fact. Continued historical and cultural congruencies between the United States and the United Kingdom-a shared language, literature, drama, history, ancestry, legal fundaments, concepts of human rights, parliamentary systems of governance, and close economic ties-endowed a beguilingly cozy patina to the American conception of England. As the great British historian of the early twentieth century George M. Trevelyan observed, familiarity made the ties tighter: In [Sir Robert] Peel’s day [1788-1850] the difficulties between the old country and the United States were still those of two branches of the same race and civilisation, kept apart by historical, political and social differences that were beginning to be less acute as England grew more democratic, and as increased trade and more rapid communication began to dispel mutual ignorance. A steady stream of British working-class immigrants had set in to the United States, forming a fresh link between the two nations and confirming the transatlantic belief that the people in Britain ‘were a very decent body, shamefully oppressed by a haughty group of Peers and clergy,’ though less shamefully now than in former years. … Dickens drew the ties closer, by revealing to Americans the existence of ‘plain people’ in England of a kind they could appreciate. (Trevelyan, 1923, p. 290)

There is a particular strain of Anglophilia that is unique to Americans, who had been convinced, like many colonists and diasporas, to consider their “new” culture inauthentic and ersatz. Imbricated in-and necessary for-American Anglophilia is the position of England as the “origin” of American culture (despite this being only partially the case).

While all three artists were invested in invoking an Anglo-American Heimat within their images, for no other artist is Stephen Keane’s description of Heimat as, “both geographical place and mythic space, the locus of national and collective identity” (1997, p. 81) more appropriate than for Abbey. Locating Abbey’s place within the bounds of nostalgia for an English past is particularly interesting. The intense American hunger for scenes of “Old England” found expression in the seven illustrated volumes Abbey produced for the New York City-based Harper’s publishing house, set in some version of historic England but intended for American audiences. The subjects of these volumes ranged from Robert Herrick’s poetry, old English songs and poetry in Old Songs and The Quiet Life, to illustrated volumes of Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies, and two different texts by Anglo-Irish playwright Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774): his classic 1771 comedy She Stoops to Conquer and his 1770 poem, The Deserted Village, which laments the depopulation of the rural countryside as a result of enclosure.

In 1902, Harper and Brothers published Abbey’s illustrated version of The Deserted Village. The poem itself, composed in rhyming couplets, describes a country village ultimately decimated by enclosure, relocation to cities, and immigration to America1. Goldsmith’s text juxtaposes inhabited and deserted versions of the village with a series of vignettes fondly describing inhabitants and their peccadillos. Illustrating this poem allowed Abbey to indulge in an explicit nostalgia for a lost time and place. Abbey exploited Goldsmith’s lack of geographic specificity to create an ideal Olde English village from top to bottom- and he, like Goldsmith, does this by combining features of many places to create a village arcadia. The village green line is particularly apt for this discussion: “How often I have loitered o’er thy green,” which not only eulogizes the space itself but a kind of ownership of that space. Abbey’s illustration shows an open field where a myriad of people cavort over its rolling hillocks (Figure 1).

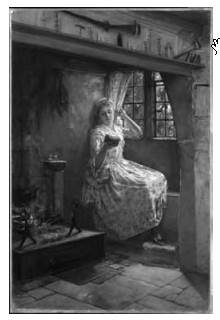

Reverence for antiquarianism permeates Abbey’s illustrations even when it contradicts Goldsmith’s text. Though Goldsmith deplores the luxuries of wealth in lines like “She then shines forth, solicitous to bless, in all the glaring impotence of dress” (Figure 2), Abbey is unable to make grotesqueries of the opulence he clearly cherishes. Instead, the artist revels in the high wig and furbelows festooning the ballgown of an aristocratic lady. Similarly, his illustration for “But the long pomp, the midnight masquerade…” (Figure 3), which shows a scene from an eighteenth-century masquerade ball, luxuriates in the heavily embellished ballgown and manners of a bygone era rather than exposing the gentry’s hypocrisies as Goldsmith intended.

Goldsmith’s condemnation of the depopulation of the rural countryside and concomitant sense of loss would have spoken directly to Abbey’s own fetishization of historical England. However, the irony that an American artist illustrates a lamentation of the emptying of the English/Irish countryside is best displayed in Abbey’s image for “Downward they move, a melancholy band Pass from the shore, and darken all the land” (Figure 4). The poem’s negative view of immigration to America (insofar as it depletes the English countryside of its inhabitants) is gently contradicted by Abbey’s rather sprightly treatment. Along with his unwillingness to martyr his gloriously attired aristocrats on Goldsmith’s altar, Abbey’s optimism subverts the writer’s message.

Figure 1 Edwin Austin Abbey, “How often I have loitered o’er thy green” - illustration for (Goldsmith, Dobson, & Abbey, 1902), undated. Pen and ink, 34.6 x 48.9 cm (13 5/8 x 19 1/4 in.) (sight). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Collection, 1937.1202.

Figure 2 Edwin Austin Abbey, “She then shines forth, solicitous to bless, in all the glaring impotence of dress” - illustration for (Goldsmith et al., 1902, p. 87), undated. Pen and ink, 44.5 x 27.3 cm (17 1/2 x 10 3/4 in.) (sight). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Collection, 1937.1226.

Figure 3 Edwin Austin Abbey, “But the long pomp, the midnight masquerade…” - illustration for (Goldsmith et al., 1902, p. 79), 1890. Pen and ink, Composition board, 45 x 28.7 cm (17 11/16 x 11 5/16 in.) (sheet). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Collection, 1937.1223.

Figure 4 Edwin Austin Abbey, “Downward they move, a melancholy band Pass from the shore, and darken all the land,” illustration for (Goldsmith et al., 1902, p. 99), undated. Pen and ink, 50.2 x 28.9 cm (19 3/4 x 11 3/8 in.) (sight). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Collection, 1937.1231.

Abbey’s images-moments of leisure, sport, or romance-celebrate an idyllic recent past. Indeed, Abbey cannot help but celebrate all aspects of the eighteenth century, including the very gentry Goldsmith’s poem deplores. Goldsmith’s poem “The Deserted Village” acts as a potent metaphor for the artists under consideration in an almost perfect proxy for the nostalgia prevalent in Boughton, Abbey, and Millet’s oeuvres: this backward-looking poem remonstrates against the loss of an older, more picturesque way of life. Abbey’s artistic pluperfect compounds Goldsmith’s nostalgia, and in this it relates both to the revivalist drive of grand manner portraiture of John Singer Sargent and to the elegiac landscapes of Albion popular amongst American landscapists at the time. Each genre is indebted to the idea of England as a mythical place, and these images are no exception.

Images set in the American Colonies (roughly 1607-1776) could be counted as part of this English past-Colonists were technically British subjects, after all, and Boughton sets several of his pictures before those national ties were cut by the American Revolution. George Henry Boughton was born in Norwich (UK) but raised in upstate New York, and a number of his paintings from 1850s through the 1890s evidence a fixation on a lost, specifically Colonial American, history. Boughton’s Pilgrims Going to Church (1867, Figure 5 is the best example of this tendency: the viewer peers through a wood on a snowy day to see a group of fourteen or so people trudging through the white and brown landscape. Two of the four or five men holding muskets look out at the viewer, emphasizing the anachronistic act of viewing-Can they feel our gazes across the centuries? And who are we-are we the Native threat, are we watching through time? Furthermore, this example of historical simulacra does not represent actual recorded events and therefore cannot be called a “history painting” in the same way as David’s Oath of the Horatii. Boughton’s specialty was what art historian Jochen Wierich calls “the domestication of history” (1998, p. 3): genre scenes of colonial Americans or contemporary Dutch peasants, which do double work as narrative images and period pieces. Pilgrims Going to Church was a nineteenth-century vision of the seventeenth century: at its most basic, the picture is incorrect in its placement of church-goers trudging through snowy woods, as the meeting houses of early settlements would have been located in the center of the settlement and surrounded by other structures, thus obviating the need to walk there in single file. There are other inaccuracies, such as the fact that the arms carried by the men are anachronistic nineteenth-century rifles, not muskets (Glesmann, 2002, pp. 6-7).

Boughton also produced a series of full-length studies of young women from Colonial American history, including Priscilla (1879), Rose Standish (1881, Figure 6, and Hester Prynne (1881). Along with images like The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers (1869), The March of Miles Standish (1869),2 and New Year’s Day in Old New York (1882, Figure 7, Boughton’s images evidence a fixation on a lost, specifically American, history. Boughton particularly cherished literary sources. Longfellow’s extremely popular poem “The Court-ship of Miles Standish” (published in 1858) takes as its subject the apocryphal love story of Priscilla Mullins and John Alden, Mayflower passengers and Longfellow’s direct ancestors. Longfellow presents one of Priscilla’s speeches as a lament for her Old English home:

Figure 5 George Henry Boughton, Pilgrims Going to Church, 1867. Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 132.1 cm (29 x 52 in.). New York Historical Society, The Robert L. Stuart Collection, the gift of his widow Mrs. Mary Stuart. S-117. Image from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, digital file from b&w film copy neg., reproduction number LC-USZ62-3291, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc. pnp/cph.3a06801.

Figure 6 George Henry Boughton, Rose Standish, 1881. 51 x 27 in. Illustration in (Blackburn, 1881, p. 14).

Figure 7 After George Henry Boughton, New Year’s Day in Old New York, from “The Graphic” Christmas Number, December 2, 1882. Color wood engraving [print]. Image: 11 13/16 8 9/16 in. (30 × 21.7 cm). Sheet: 15 3/4 × 11 1/4 in. (40 × 28.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Donato Esposito, 2015. 2015.653.13.

“I have been thinking all day,” said gently the Puritan maiden,

“Dreaming all night, and thinking all day, of the hedge-rows of England,- They are in blossom now, and the country is all like a garden;

Thinking of lanes and fields, and the song of the lark and the linnet,

Seeing the village street, and familiar faces of neighbors,

Going about as of old, and stopping to gossip together,

And, at the end of the street, the village church, with the ivy

Climbing the old gray tower, and the quiet graves in the churchyard.

Kind are the people I live with, and dear to me my religion;

Still my heart is so sad, that I wish myself back in Old England.

You will say it is wrong, but I cannot help it: I almost

Wish myself back in Old England, I feel so lonely and wretched.” (Longfellow, 1858, p. 36)

Boughton’s painting of Priscilla depicts a thoughtful young Puritan woman trudging through the snow with a book. It is a contemplative scene, the “Puritan maiden” seen in profile with timbered houses in the background and the cold waters of the Massachusetts Bay in the distance. Boughton emphasizes Priscilla’s youth and luscious body by the way she clutches the skirt of her dress, pulling it taut and exposing her ankles as well as the shape of her buttocks. That she is a “Puritan maiden” (i.e., a virgin) emphasizes the delicious inappropriateness of her innocent fleshly display. As Boughton’s visions of an idealized and exciting (Guns! Indians! Nubile Puritan maidens!) American past demonstrate, the desire to fetishize Anglo-American heritage was neither limited to American-born artists nor was it restricted to representations of English history.

Francis Davis Millet-universally known as Frank-was born in 1846 in Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, trained at the Royal Academy in Antwerp, and died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic on 15 April 1912. Millet’s easel paintings reflect his dedication to narrative stories in a variety of historical periods, with a focus on eighteenth-century and early-nineteenth-century interior scenes. In general, Millet’s work strives to recuperate “Golden Ages” of various dates-Classical Greece, Puritan America or Holland, or Regency England-represented in naturalistic scenes that were generally domestic rather than heroic. The American Colonial era appears regularly throughout Millet’s oeuvre, perhaps because of his family’s ancestral ties to the aforementioned Mayflower passengers John Alden and Priscilla Mullins. The recursive capacity of Millet’s interiors demonstrates the seductive-ness of nostalgia on a grander scale than Abbey’s illustrations. Now largely fallen from favor, Millet’s genre images such as Love Letter evince a sentimental yearning for the past. Unlike portraits, which are inextricable from questions of class and privilege, and unlike images of landscape, which tap into specific agrarian fantasias, Millet’s work allows and creates imaginative access to reconstituted history.

The Love Letter (before 1893), which takes place in a white-walled room in the Regency era, is one of several images that are placed in period settings without being impelled to do so by the narrative. The Love Letter is one of Millet’s series of English period domestic interior scenes that identify a female subject and use costume-in this case, the high-waisted dress indicative of the Regency era-to place the action in a recent past. Millet brings his early experience with orientalist staging to soft English interiors glittering with silver and silk wall draperies, as though these plush interiors are rare birds being detailed. In its rehearsal of lighter subject matter and nostalgic rhythms, Millet’s repetition of domesticity among the well-to-do-indicated here in the silver and paintings that adorn the room-carries with it the whiff of wistfulness. In their active anti-modernity, they may also be understood as opposition to avantgarde experiments happening in France at the time. Such fixation on the past and creation of historical simulacra indicates a desire to place oneself (that is, the artist/viewer) in relation to that past, as part of developing and confirming self-identity and place in society. Supporting such a reading is the conspicuous presence of an even older picture in the background, which attests to the social position of the family depicted while simultaneously performing that exact legitimating function for the owners of The Love Letter itself in a neat circularity. Yet Millet’s canvas is a fabulation, rather than a document.

One of Millet’s best-known pictures, Between Two Fires (1892, Figure 8 combines his later interest in narrative with his earlier Dutch-inspired paintings-period costume and setting with sunlight in a light room, contrasting with judiciously chosen moments of darkness. The title refers to the two women in between which a behatted man finds himself (an alternate title could be Between a Rock and a Hard Place). The humor of the image comes not only from the man’s slightly alarmed expression but also, pointedly, from his identity as a “Puritan parson or student”-a profession typically represented as strict, un-yielding, and humorless (as in Millet’s The Black Sheep and Abbey’s Stony Ground, 1884, Figure 9 (Coffin, 1912, p. 644). The inversion of power relations-the man must wait for these two irate women to serve him his food-provides some of the humor of the image and heightens the approachability of the work. The facial expressions and poses, particularly that of the man, show Millet at the height of his compositional power. This is, perhaps, Millet’s masterpiece. The handling of paint is clear and sure, the composition compelling, and fussy incident is kept to a minimum. Certain objects Millet depicts in Between Two Fires would have been familiar to the viewer from the fringes of memory: a cuckoo-clock, candle, serving implements, etc.-items owned by a grandparent, maybe passed down or hung on a wall: heritage items. In comparison to earlier pictures like A Cosey Corner (Figure 10, crammed full of bric-a-brac (Simpson, 1990, pp. 71-72), the interior is spare. The costumes are essential to understanding the image, in this case that the man’s collar and hat identify him as a Roundhead (that is, a Puritan supporter of the Parliamentary Party during the time of the English Civil Wars from 1642-51). Like that of its nineteenth-century American relative, the English Civil War was famous for pitting neighbors and family members against each other. The conflict was romanticized by nineteenth century interpretations like William Frederick Yeames’s And When Did You Last See Your Father? (1878). Set on the fringes of memory, Millet’s period scenes play in the interstices between a hazy past and an all-too-familiar present.

Figure 8 Frank Millet, Between Two Fires, c. 1892. Oil on canvas, 74 x 93 cm (29 1/8 x 36 5/8 in.). Tate, London. Chantrey Purchase 1892. N01611. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported). https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millet-between-two-fires-n01611.

Figure 9 Edwin Austin Abbey, Stony Ground, 1884. Gouache on paper (watercolor), 101.6 x 152.4 cm (40 x 60 in.). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Abraham Adler, 70.7.

Figure 10 Frank Millet, A Cosey Corner, 1884. Oil on canvas, 92.1 x 61.6 cm (36 1/4 x 24 1/4 in.). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of George I. Seney, 1887: 87.8.3

Yet these seventeenth and eighteenth century English pasts are only some of the many different pasts from which to choose. As has been demonstrated, the English past has been a continual source of myth, cherished by both British and American constituencies. Other time periods could be evocative in different ways: the middle ages were dark and difficult, while the time of the English Civil War was tragically romantic, and the Dutch golden age was musical and jolly (generalizations, to be sure). In contrast, the Classical tradition was too far from immediate collective memory to be instantly evocative to the viewer. One must distinguish here between Millet’s classicizing paintings like An Autumn Idyll (also 1892, Figure 11 and his English interiors like Between Two Fires. Though both works are set in the “past,” the generalized idyllic space of the former gives little insight into the lives of the figures depicted-it is pleasant to look upon-while the highly specific setting of latter encourages the viewer to parse and create a narrative for the scene (Fletcher, 2003). Generally, because the classical past was exponentially more distant from the present than, say, the Interregnum, images set in a classical past encouraged a cerebral, rather than a visceral, connection that was given to allegory rather than sentiment. By providing universal access to lofty themes, cloaking current events in an ancient Greek or Roman mantle could elevate the tenor of the scene, as Jacques-Louis David and Thomas Couture (1815-1879) understood in Oath of the Horatii (1784, Louvre) or Romans of the Decadence (1847)- no need to actually be Greek or Roman. (The Roman history of Britain-from ancient Londinium to Hadrian’s Wall-provided a tangible connection with ancient scenes that would have been impossible in America, though of course American artists also created classicizing scenes.) In any case, while an anachronistic scene might be out of reach of personal memory, setting the scene in a recent past could place it within access of collective memory. Albion-the mythic England of King Arthur and the quaint England of Oliver Goldsmith-was a flexible temporal construct for the three artists in question. Al-most diametrically opposed to the modernity sought by certain of their contemporaries in France, Abbey and Millet’s evocations of anachronistic English pasts helped their audience locate themselves vis-à-vis historic England by literally imagining (image-in: to put the image of oneself in) themselves in the world of the image using sensory cues found in the image and by the source text(s). Such synesthetic devices included information on not only what these historical spaces looked like but how they sounded, smelled, felt (and in images like Millet’s Between Two Fires, even how they tasted). Similarly, the accretion of specific historical details in a work like Abbey’s watercolor The Wandering Minstrels (1890, Figure 12 -also a Georgianera scene populated by figures wearing tailed coats and buckled shoes and set amongst picturesquely deteriorating timber houses with mullioned windows-strengthens the image.

Whether it is Abbey’s volume of old English songs-illustrated by meticulously re-searched drawings-or Boughton’s nubile Colonial maidens, these artists produced an England that was tidy, comfortable, and picturesque, aligning closely with conceptions of “home” and associated with the cozy, the true, “the traditional, the usual and the hereditary [which] is dear and familiar to most people” (Jentsch, 1997, p. 8). Illuminative for this formulation is the German notion of Heimat, which is literally translated as ‘homeland’ or ‘rootedness in a place of origin,’ that conflates the motherly and the homely3. Beyond this basic understanding of ‘homeland,’ Heimat refers to both geographical place and mythic space, the locus of national dispute and collective identity. … Released from geography into the conceptual, Heimat also allows a revisiting of historical time through subjective memory. It is always past. … As place, Heimat exists as village community; in time, it exists as tradition. Heimat is the parochial in history. (Keane, 1997, pp. 81, 82)

Figure 11 (right). Frank Millet, An Autumn Idyll, 1892. Oil on canvas, 54.8 x 33.6 cm (21 9/16 x 13 1/4 in.). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the executors of the estate of Colonel Michael Friedsam, 32.844. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, CUR.32.844.jpg).

Figure 12 Edwin Austin Abbey, The Wandering Minstrels Strolling Players, 1890. Transparent and opaque watercolor with graphite underdrawing on wove paper, 62.9 x 89.5 cm (24 3/4 x 35 1/4 in.) (inside frame). Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Edwin Austin Abbey Memorial Collection, 1937.2685.

The manifestation of this cultural incongruity in Americans in England follows specific lineaments, most eloquently conveyed by the landscape architect Fredrick Law Olmsted, visiting England as a young man for the first time in the 1840s:

Parting the foliage with my hands, I looked out upon a cluster of low-thatched cottages, half overgrown with ivy; a blooming hawthorn hedge, enclosing a field of heavy grass and clover glistening with dew; a few haystacks; another field beyond, spotted with sheep; a group of trees; and then some low hills, over which the dawn was kindling, with a faint blush, the quiet, smoky clouds in a grey sky. It may seem an uninteresting landscape, but I gazed upon it with great emotion, so great that I wondered at it. Such a scene I had never looked upon before, and yet it was in all its parts as familiar to me as my native valley. Land of our poets! Home of our fathers! Dear old mother England! (1852, p. 99) [my emphasis] By explicitly positioning the English countryside as maternal, Olmsted portrays the relationship between England and America as one of parent/source and child; an American’s trip to England thus explicitly becomes one of homecoming. If we take as given that such reenactments metaphorically locate the past as a foreign country that can be visited and colonized (Lowenthal, 1985), then Boughton, Abbey, and Millet can also be positioned as travelers both in geography and in time. They become guides to what cultural theorist Patrick Wright (2009) describes as “Deep England,” a collectively imagined, pseudo-historical England that is “founded on an imagined participation immemorial rather than any mere legality” (p. 79). For Americans, images of an English past were reassuringly familiar and yet exotic at the same time, simultaneously accessing both a “homeland” and a timeless past-the basis, perhaps, for an analogous “Deep America” found in Boughton and Millet’s work. Closely related to a native British nostalgia for Deep England, America’s separation from its erstwhile English “homeland” simultaneously constitutes the rupture essential to the nostalgic drive and begs for a return to that origin.

Appropriated here to the two-dimensional form and the trans-temporal subject of domestic genre scenes, Heimat is indelibly linked to nostalgia. In aggregate, the repetition of nostalgic themes also represents the drive to find a resonant source of personal history among these artists, whose oeuvres occupy a liminal space between American and British, past and present. As philosopher Janelle Wilson suggests, nostalgia “helps to facilitate continuity of identity. … Nostalgia recollection gives us the opportunity to observe and juxtapose past and present identity” (Wilson, 2005, p. 35). These time traveling episodes are both performative and constitutive of identity, supplemental to an ontological understanding of one’s self in the world as well as “a quest for an authentic domain of being” (Frow, 1991, p. 129). These images, therefore, must be repositioned as actively constituting identities by way of a compulsive retrospection and return to the home/motherland. Yet this constant repetition of the past-the antique rhythms of Boughton’s colonial maidens, Abbey’s quiet tea-drinkers and poets, and Millet’s romantic Regency and Cavalier mises-en-scènes-denotes the unmoored feeling of the present. Semiotically speaking, the simulation of the past signals its increasing distance and estrangement from the present, even as it “preserves” that past. In other words, the more the past is invoked, the further it recedes. Images of historical domesticity-of interiors refulgent with warmth and anecdotal details-advertise the present day lack of those objects, manners, and mores, enacting Slavoj Žižek’s interpretation of the Lacanian drive:

[T]he image that most appropriately exemplifies drive is… the ethical compulsion which compels us to mark repeatedly the memory of a lost Cause. … This is how Lacan defines drive: the compulsion to encircle again and again the site of the lost Thing, to mark it in its very impossibility - as exemplified by the embodiment of the drive in its zero degree, in its most elementary, the tombstone which just marks the site of the dead (Žižek, 2002, pp. 272-273).

The desire to inscribe oneself in-or, as Žižek would have it, around-the past is palpable in a painting like Millet’s How the Gossip Grew, where the artist’s wife Lily is placed in a fully imagined eighteenth century sitting room, reconstituted as a historical figure even as she exists in the present. Yearning for Old “Mother England” is a desire for not just the place but for the place in time: travel through multiple dimensions.

To paraphrase sociologist Judith Adler, travel through time is world-making (1989, p. 1368). Abbey’s illustrations, and Millet’s and Boughton’s paintings hold up Anglo-American histories as worthy of commendation and remembrance. Abbey’s illustrations in Old Songs commemorate snippets of the past that are historically unimportant, but whose depiction reifies their significance. This is part of their magic, for, as Wilson states:

[N]ostalgia can be viewed as a picture of our meaning. There is something strongly transcendent to it-looking for more, looking for a purpose. What we are nostalgic for reveals what we value, what we deem worthwhile and important. Through our nostalgia, we are recreating happy memories, pursuing happiness in the past. We may face constraints in the present, but in the past there are no constraints. (2005, p. 26)

From subject matter and style to reception, the domestic works of Abbey, Millet, and Boughton are indicative of a continuing concern dear to the American psyche: a search for origins and legitimacy through the construction of fantasies of heritage. There is a further paradox at work here: though England was central to the origin myth of American culture, it was, nevertheless, still foreign. Frow casts this estrangement as “one of the period’s key metaphors for the condition of modernity ([which] is also one of the central conditions of tourism, where the Heimat functions simultaneously as the place of safety to which we return and as that lost origin which is sought in the alien world)” (1991, p. 135). For American artists like Abbey, pilgrimage is not just to a specific point on the map (e.g., Stratford-upon-Avon), but to a generalized historical space.

Pictures like Boughton’s Pilgrims Going to Church, Abbey’s illustrated volumes for Harper’s, and Millet’s Between Two Fires do more than just actively reconstruct the past: they actively mythologize it. In so doing, these images demonstrate an increasingly recursive facet of contemporary American identity: nostalgia for an imagined, possibly fantastical, history that legitimates our present and slips ever further from our grasp. The irony that this study of domestic quaintness could at all relate to some of the most xenophobic and retrogressive tendencies in recent political history must not be allowed to escape the reader. The popularity of Make America Great Again (MAGA)-the slogan of now-President Donald J. Trump during his presidential bid in 2016-with its generalized dissatisfaction with the present without a clear identification work understanding of the explicitly historicized desire for that past-represents the weaponized metastasis of a return to a beatific origin. While, grammatically speaking, Make America Great Again is an imperative present with implication for a future, it is predicated entirely on the disentombment of a past “great” America4. Which past, exactly, is left tantalizingly unidentified. This lack of specificity allows the “again” referent to oscillate: a past of Reaganomics? Of 1950s gender restrictions? Of 1960s space exploration? Of 1990s financial blooms? Of manifest destiny and westward expansion? All of these are implied simultaneously. By placing MAGA in context with the seemingly benign paintings of Boughton, Abbey, and Millet, perhaps we can also identify 1) that the artworks in question are themselves less innocuous than they appear, and 2) that the estrangement from, loss of, and fetish for historical identity at of the heart of the MAGA fantasy may signify the emptiness at its heart-Žižek’s “tombstone which just marks the site of the dead” (2002, p. 273).

In fact the story of American artists in England in the late nineteenth century is part of a larger and longer narrative of the post-colonial transatlantic sphere writ large. The appeal of searching through time to gain access to mythic heritage and the authenticity with which it comes continues to be felt in anxieties undergirding contemporary American politics. In neither case, however, as I hope I have made clear, has this origin existed anywhere but in the imagination: the sacralization of the past “is an act not only of re-contextualization but of invention…even the most ‘authentic’ traditions are thus effects of a stylized simulation” (Frow, 1991, p. 133). The works of Abbey, Boughton, and Millet manifest a hyper-nostalgic vision of a unified Anglo-American transatlantic past that is only histrionically-that is to say, impartially-accurate. Familiar yet aloof, these images straddle the boundary between present and past, British and American, Heimatlich and foreign, known and unknowable.