The ontograph

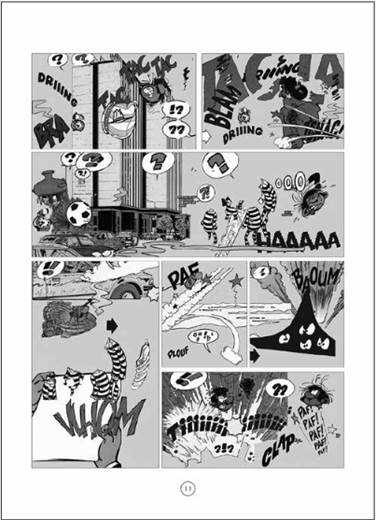

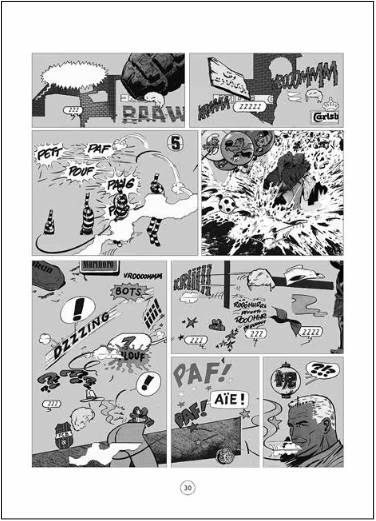

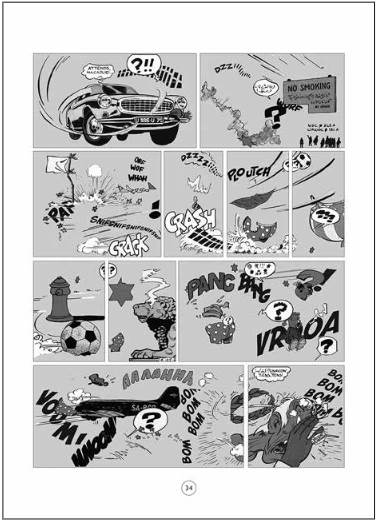

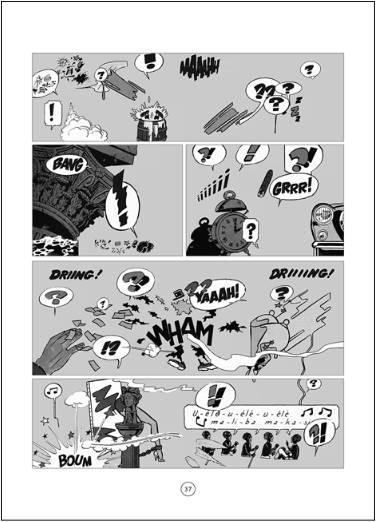

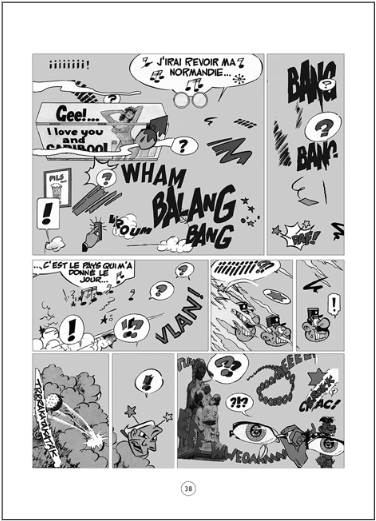

...puffs of smoke, falling pianos, mildew, shark wings, onomatopoeia, movement lines, the Dalton Brothers, cellulose oxidation and sweat droplets.

In his book Alien Phenomenology, video game designer and philosopher Ian Bogost, rediscovers the concept of the ontograph. The term consists etymologically in the determinative “onto” that refers to being or reality and the determinatum “graph” denoting forms or processes of writing, representing, recording, etc. Ontography is therefore a catalogue of being and an elegant representation for Bogost’s complex philosophical program of flat ontology. In this paper I examine my book Abrégé de bande dessinée franco-belge (Figure 1) and how its composition process was informed by the ontograph’s operational clarity.

The term ontography has been used in many different research fields ranging from geography (Davis, 1902), to Gothic literature (James, 1904) and Kantian metaphysics (Harms, 1941). The first occurrence of the term ontography and the one I would like to bring here is found nevertheless much earlier (Stadler, 2015), in a short article from Karl Christian Friedrich Krause published in 1822. In this text, the philosopher argued in favour of an essential language (ontoglossa) consisting of primitive sounds (ontolaly) and signs (ontography) that allow for a seamless interoperability and a flawless translation between different expression modalities. The essential language and its proto-alphabet could form, according to the author, a universal system of signification that can perfectly account for and express the common essence of human cognition and cognizable reality. Based on a self-explaining dictionary, this essential language is independent from the natural languages or any other systems of communications that have been developed through use and without conscious planning or explicit premeditation, and whose limitations ultimately were thought to hamper the development of scientific research. Besides the text’s historical fiction for a signification system that can reflect the potentialities of human cognition without the distortions of culture, Krause’s speculative constructed language with its objects that can be distributed in a multimodal fashion was an inspiring example for controlled language environments that favor reduced ambiguity like in the context of technical documentation. This paper argues that as an inscriptive strategy, in can be inspiring for comics and for the book description that follows.

Following Bogost’s intuition, the ontograph is a graphical or diagrammatic representation that provides concise and detailed information about the units and the ways they relate with each other in a particular situation. Ontographic information is organized in ways that not only appeal to multiple sensual modalities, as Krause intuited, but can also take multiple forms. Examples of ontographs would include shopping lists, the “exploded views” of technical drawings (McLellan, 2019), the cross-section diagrams of manuals revealing the inner function of products (Warren & Woddward, 2018), Bogost’s own generator of random wikipedia API queries aptly named Latour Litanizer1, or just any assortment or compendium where, without any additional need of interpretation, the objects’ mere belonging to the same group reveals “the repleteness of units and their interobjectivity” (Bogost, 2012, p.38).

There is a rich variety of models of visual thinking and exceptional expressions of visual cognition coming from diverse cultural fields and in the Humanities. Ontography is an elegant representation of what Bogost calls flat ontology; a system where “the abandonment of anthropocentric narrative coherence in favor of worldly detail” (Bogost, 2012, pp. 41-42) allows unusual associations between singular objects to emerge. Objects can be described according to philosopher Graham Harman as “anything that has a surplus beyond its constituent pieces and beneath its sum of total effects on the world” (Harman, 2018, p. 51). An ontograph would function as an exercise in the “democracy of objects” where every object, small and large, real or fictional, will be displayed bare, claiming equal ontological footprint. The list’s structural non-hierarchical juxtaposition would therefore allow singular and unpredictable objects to be contemplated as such: without being reducible, in infinite regress, as aggregations of smaller bits, an operation Graham Harman calls undermining, or on the other hand overmined, trapped in a sort of pre-individual state and entirely existing as parts of a larger system or a meaningful arrangement. Both of these operations exemplify the negation for a plurality of being; they withhold the emergent realities that can happen in all levels of experience by the enforcement of a supplementary existence in the life of an object.

Published in 2018 under the catalogs of eight different comic book publishers, Abrégé de bande dessinée franco-belge is an attempt to investigate the Franco-Belgian tradition of bande dessinee through the lenses of its objects. Presented as an ontograph, the book reads as a multi-layered, multivoiced piece. It is a reflection on the particularities of a local comics industry that has been seminal in the evolution of the comics medium, but whose national and linguistic gravitational pull, in the midst of globalized industrial flows, has been gradually diminishing. Franco-Belgian comics have many distinctive marks including their signature humor, the graphic style and modes of address, but also their format, which has been a constitutive factor for this project (Figure 2).

The book’s format

In 2005, Jean-Christophe Menu, the publisher of L’Association publishes a biting manifesto, Plates Bandes. In the book, he explicitly positions l’Association as an avant-garde, a group of dissident authors, whose work could not be contained in France’s publishing market-driven landscape of their times. These artists wanted to use comics as an expressive medium. In his manifest, Menu was attempting to insulate the Association’s book catalog from the sensibilities of the Franco-Belgian mainstream comics industry. While words such as “avant-garde” rely on sets of cultural appreciation criteria that assume distinctions between high and low form of artistic engagement (Beaty, 2007), and might seem dated to the contemporary reader, Menu’s claim to belong in a counter-institutional movance with a certain modernist ethos, thematizes the conflicting relations of the comics industry with contemporary art. His infectious negativity has been rarely expressed in the comics world, or in the counter-cultural comics scene of the french speaking underground. Plates Bandes departs from the prevailing assumptions according to which the format of a book is a transparent signifier whose sole function is to frame the content. Now seen as a premonitory call, in the twilight of massive remediation towards the digital, Plates Bandes posits the question of the format as the most salient aspect of the French comic book industry. Menu christens the national industrial standard for comic books in the french-speaking market: 48CC, is the abbreviation for a forty-eight-page hardbound full-color printed album, whose predecessor can be found in children’s books from the 1950s and that has now been largely adopted by mainstream publishers Dupuis, Dargaud, Lombard and Casterman for their serialized narratives. By this coinage, Menu attempts a performative utterance; he reveals how comics rather than being the aspiration of an artist and a publisher, have to be thought as products defined by an industrial and a commercial ordeal: the complicities and conflicting interests of workflow management, format standardization, economies of scale, paper bulk orders, reader attention spans, shelf space and collectors’ best practices. In the center of the book standardization process in the publishing microcosm, Menu blames the corporate ethos of publishers, and the retailers who did not have much use for Association’s extra-ordinary formats. He barely absolves the role of the reader, receptive in participating in what the author disdainfully calls “La culture BD” where readers and fans alike, accumulate entire series and comics derivatives (Menu, 2005, p.20) and are prone to follow the mindset of speculative philately. The ubiquity of the 48CC format, and the various camp practices organized around its collections and discussions, can be seen as an impoverishment compared to previous publishing practices, where a multitude of different formats, layouts, technical features constituted a much more varied publishing landscape against the uniform landscape of a “monoculture” (Löwenthal, 2006). It certainly functions also as an insulation from the larger book industry where purposely comics in french are not described as books but as albums. The standardization of the comics album that took place in the 80s comes, according to Menu, as a natural step of the withdrawal of the Author. Mainstream comics are no longer described so much as author productions but as situated in a constellation of descriptives and production categories, such as Genres, Heroes, Series and album Formats (Menu, 2005, p.18). Menu capitalizes all those terms, ironically conferring them equal value as the Author’s name. Nonetheless, his manifesto historicizes the consolidation of the mainstream, as an important step towards the creation of the authorial ethos and the rediscovery of the avant-garde in comics, a term that might produce the counter-effect of further confining comics to the status of a paraliterary medium (Baetens, 2012), buffering any meaningful exchange with other book arts and publishing practices.

Plates Bandes doesn’t have only the merit to be a rare materialist analysis of the comic book format coming from a celebrated publisher, and an art worker. Menu articulates a reflection on the particularities of a dominant national market and the challenges it faces in the midst of increasingly globalizing flows in the production and appreciation of comics. This situation is naturally not specific to the comics industry. Already in 1982, Robert Darnton in a seminal essay argued that book history cannot easily be satisfied by narrowly defined disciplinary research and analyses based on national economies. It had to take the form of an intersectional, transdisciplinary scholarship, mapping consistent patterns and intersections along global economic, social, legal and political forces and processes. He went to describe the book industry and its global dimensions as a “communication circuit” (Darnton, 1982), a transnational industrial network shaped by an international “republic of letters” consisting of book professionals such as authors, publishers, printers, shippers, booksellers but also readers, critics and scholars, that aggressively compete for the products of cognitive labour. Often situated at the forefront of semiocapitalism, these operators and professionals of the book industry, and one might add the comics industry, speak many different languages, come from different cultures and often their practices cross linguistic, national and market boundaries. The standardization of the 48CC, and its national appeal, whose relevance was rather limited in other markets such as in US or Japan has been a short-term solution for a market who soon was to be globalized. The products of global market increasingly exhibit “an enormous variety in production, distribution, consumption, and formal and thematic characteristics” (Lefèvre, 2010). These cultural products gain international popularity, and are progressively competing with local industries for a market share (Suzuki, 2010). In Plates Bandes, Menu uses the example of the manga industry to substantiate his point: contrary to the massive standardized national paperback newsprint books produced in Japan, only author-based manga works are imported in Europe. Standards don’t travel, authors do2. This begs the question: what is the future for national standards and formats in a globalized book industry? Abrégé addresses this question by producing a quasi-archaeological artifact that accounts for the Franco-Belgian industry’s format dominance (Figure 3).

The Selection Process

In one single day, I visited a dozen second-hand bookstores in Brussels, where I acquired forty-eight albums, of 48CC standard format. The choice to address the second-hand book market was a strategic one. In Belgium, the spontaneous small town conventions and the seasonal book fairs with their bouquinistes, play an important part in extending the economic cycle of a comic book. Used books are also richer in inscriptions than new ones. They usually carry an assortment of additional marks that indicate the social and economic activities, and the commercial routines that composed the book’s meaning-signifying trajectory. These inscriptions are bookseller’s price marks, the various book dedications, the ownership signature, the library stigmata with their date slips, card pockets, catalogue information and inventory control strips but also the signs that manifest of the social life cycle of the book such as page corner doodles, the tear and wear marks, mildew traces, coffee stains, cover degradation and others. For an ontographic understanding of bande dessinée, the distinction between textual and pictorial elements that conventionally account for comics craftsmanship, and the insciptions of the social-economical life of book here collapses; each inscription is part of a material language that is expressed on the same informational level of the artifact’s substrate.

Once the books were collected I carefully scanned them from cover to cover. A total of 2400 digital files were stored locally and were named according to a simple classification rule: files carried the book’s title followed by the page number, i.e. Gil Jourdan (29). The files coming from different books but carrying the same page number, were grouped together in a single folder (named after that number), i.e. in the folder “29”, one can find all the twenty-ninth pages of the forty-eight collected books. The content of each page of the final book Abrégé, will be an edited version of all the pages carrying that same page number from all the different books (Figure 4).

The database

Following the principles of ontography, I started by establishing a list that indexed all the elements that I personally considered to characterize the tradition of the Franco-Belgian comics school: This was a non-exhaustive list, a sort of a partial knowledge, an intuitive subjective repertoire of what Belgian comic books feel like to me. The database grouped elements of visual language that became popular through these very same works (line movements, hovering dark clouds and sweat droplets), iconic running jokes and graphic material from the comics “genome” (digesting snakes, falling pianos, shark wings and body-shaped holes), discursive representational forms (racial and sexist stereotypes, historical, architectural and geographical references, product advertisements), textual devices (all different sorts of bubbles, and rhetorical utterances such as constructed language, rebus, misspellings, references to song lyrics and graphic obscenities), meta-narrative devices (directional arrows, black panels, asterisks and self-referential marks). Following the precepts of flat ontology this list could not limit itself in the graphic content but should also engage with the material properties of the book as an object. Inspired by Bogost’s description of the ontograph as “a crowd, not a cellular automaton […], [a] landfill, not a Japanese garden” (Bogost, 2012, p.59), the database included a variety of features that I would expect to specifically locate in the second-hand book market; a variety of paratextual information such as author signings, collector’s insignia, paper discolouration, laid-in documents, mildew degradation, torn pages, shelf wear, general marginalia, etc. All the elements were eventually attributed a numerical index. Wherever I felt it necessary, I added a footnote for further elaboration or disambiguation, related for example to an element defined too roughly, or to a categorical overlap, which I didn’t necessarily mind. While there is an arts pedigree of humorous quasi-scientific repertories of vernacular collections, my only goal was to produce a clear taxonomy that would allow me to lay bare all the elements that I personally considered to belong in the Franco-Belgian tradition of bande dessinée (Figure 5).

The score

Once I established the taxonomy indexing the elements of the Franco-Belgian bande dessinée, I produced a two-axis diagrammatic score3 that would eventually allow me to visualize how the elements of my typology were distributed in the pages of the books I bought. The score’s horizontal axis, listed the source books, grouped by vague affinity, not unlike the instrument families in the multi-staved sheet for orchestral music (strings, percussion, woodwind, etc). Some book titles contained in their stories recurrent graphic leitmotivs that could establish a sense of visual continuity in the production of the final Abrégé book. Other books were deemed to provide the equivalent of a musical drone or a sheet of sound with their uniform colorfieds, while others, like percussion instruments could only be used as sparks, in order to accentuate specific events. The vertical axis represented comics’ expression of time. It contained 48 parent columns (each accounting for every single page of a 48CC album) that was further subdivided in child columns that referred to the individual panels. The objects that made the initial index and that could be harvested from the collected books were to be cited in the score according to their origin (book) and their placement in the book volume (page and panel number). Although the score in its present state was an empty structure, it could already bring certain aspects of the operation in selective focus: the score certainly defined the overall duration (the length of the narrative) with its discreet subdivisions of time and through the layering of the different books, the score was already setting the conditions for an interplay that delineated the field of all the possible narratives that could unfold once the different books were percolated through the database of my ontograph.

The composition

During this stage, I proceeded to what Kirchenbaum defined in a personal exchange with Katherine Hayles as rapid shuttling: I repeatedly switched between an interpretation of the collected books based on close reading, and how they responded quantitatively in terms of the ontograph’s database I previously created. I carefully located the elements and, taking in account their page and panel number, I registered their particular instantiation by marking their attributed index number in the empty score. At that stage the composition graphed all the elements that could be mined from the specific list of second hand 48CC comics that were bought. I now only had to retrieve from the folder the digital file and isolate the element by erasing all the surrounding information with the use of a digital photo editor. The isolated elements were marshaled into the empty panel structure of one of the books that were purchased, Giraud’s Arizona Love. The book was expressly selected for its varied panel composition. As for the uniform background color I had to turn once again to music in order to make an informed choice: space is a determinant factor for sound production and some works, such as chamber music require specific locations in order to be performed. I decided that the equivalent backdrop feature for the purposes of my experiment will be a uniform cyan of 30% saturation that will allow the graphic qualities of this experiment to emerge (Figure 6).

Indexation and other related forms of data visualization like the exploded diagram of a technical manual, run counter to the temporal sequencing of the narrative, conventionally intuited to be a crucial feature of the comics medium. Although big data accumulation might ultimately collapse the difference between the narrative and the database as opposed forms of knowledge production, the discussion that culminates in the uses and abuses of data as a self-descriptive form of information aggregation has deep political implications that go beyond the purposes of this paper. Although comics, like poetry, is slowly moving in the world of big data visualization, procedural artistic practices that involve indexation are very marginal in contemporary comics.

Abrégé was composed following a typology of pictorial-narrative units drawn from a shared reservoir of the bande dessinée tradition. Although it utilizes the form of the database, the selection of the entries explicitly embodies the values and structures of my own understanding and experience of the bande dessinée tradition, a genre that I came to know in an adult age. Paul Stephens has argued in his article on conceptual writing, that indexical appropriation as a popular procedural strategy in contemporary practices in poetry, “demonstrates considerable self-reflexivity with respect to the conditions of its own existence” (Stephens, 2013) by enmeshing the writer in the very same processes of informatization and financialization of global media production flows they are indexing. Abrégé claims therefore the position of both a book and an archive in motion that expresses my understanding of this tradition. Abrégé mimics the 48CC by collapsing the distinction between “primary” artifacts (the original book product multiples of an industrial fabrication) and second-order commentary, except for one important feature; the book, as if overdetermined by the abundance of its own content, is bigger in size than the collected books.

Abrégé invites the readers to forensically parse the cited works by putting on display the heterogeneous objects of a local comics industry, to be contemplated as such. It points towards the constitution of new practices of indexation. It uses the concept of the ontograph as a way to present comics as objects, without requiring an interpretation that comes from the elucidation of the original narrative functionalities, or having to demonstrate the referential significance of distinct narrative units and building blocks. By merely charting the networks among reading experiences, Abrégé provides a virtually present construct of relational juxtapositions and claims the irreducibility of objects to their effects or compounds. Abrégé argues for the necessity of different modes of reading in relation to comics by exemplifying how combined modes of an approach to a text can allow new works to develop. Its objects are freed from the imperatives of the specific narrative in which they were initially implemented, and from the correlations implied by storytelling functionalities. Similar to an autopsy, the distinct narrative units and the building blocks of Franco-Belgian comics tradition are laying bare, emerging and imposing themselves as dense singularities.