Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo

versión impresa ISSN 1853-8665versión On-line ISSN 1853-8665

Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar., Univ. Nac. Cuyo vol.52 no.2 Mendoza dic. 2020

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Indirect selection for content of carotenoid in pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch) accessions

Selección indirecta del contenido de carotenoides en accesiones de calabaza (Cucurbita moschata Duch)

Rayanne Maria Paula Ribeiro 1; Carla Caroline Alves Pereira 1; Lindomar Maria da Silveira 1; Glauber Henrique de Sousa Nunes 1; Semíramis Rabelo Ramalho Ramos 2; Manoel Abílio de Queiroz 3; Matheus de Freitas Souza 1; Hamurábi Anizio Lins 1; Aurélio Paes Barros Júnior 1

1 Department of Agronomic and Forest Sciences. Universidade Federal Rural do SemiÁrido. Mossoró. RN. Brazil.

2 Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. Embrapa Tabuleiros Costeiros. Aracaju. SE. Brazil.

3 Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding. Universidade do Estado da Bahia. Juazeiro. BA. Brazil. hamurabi_a_@hotmail.com

Originales: Recepción: 02/04/2020 - Aceptación: 06/07/2020

ABSTRACT

Carotenoid quantification in food can be performed by various techniques, such as spectrophotometry, mass spectrometry, high performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, and colorimetry. The objective of this study was to verify the feasibility of indirect selection for assessment of total carotenoids in pumpkin accessions. The experimental design comprised of complete randomized blocks with two replications and three plants per plot. The treatments consisted of 51 Cucurbita moschata Duch accessions from the DCAF/UFERSA Cucurbitaceae germplasm collection and a commercial C. maxima Duch cultivar. After maturation, the fruits were harvested, and colorimetric and total carotenoid contents were evaluated. Considering the effect of accessions as random, variance components were estimated, and the genotypic values were predicted by maximum restricted likelihood (REML) or best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP). Both direct and indirect genetic gains were estimated from a selection intensity of 50%. Pulp color intensity parameters and h° angle indicated the possibility of indirect selection of accessions with higher total carotenoid contents. The ABO22 accession presented higher total carotenoid content under the evaluation conditions of the experiment.

Keywords: Cucurbita moschata Duch; Colorimetry; Correlation; Variability

RESUMEN

La cuantificación de los carotenoides en los alimentos se puede realizar mediante diversas técnicas, como la espectrofotometría, la espectrometría de masas, la cromatografía líquida de alto rendimiento, la cromatografía de gases y la colorimetría. El objetivo de este estudio fue verificar la viabilidad de la selección indirecta para evaluar los carotenoides totales en las accesiones de calabaza. El diseño experimental fue bloques completos al azar, con dos repeticiones y tres plantas por parcela. Los tratamientos consistieron en 51 accesiones de Cucurbita moschata Duch de la colección de germoplasma DCAF/UFERSA Cucurbitaceae y un cultivar comercial de C. maxima Duch. Después de la maduración, se cosecharon los frutos y se evaluó el contenido colorimétrico y total de carotenoides. Considerando el efecto de las accesiones como aleatorio, se estimaron los componentes de la varianza y se predijeron los valores genotípicos mediante la máxima verosimilitud restringida (REML) o una mejor predicción lineal e imparcial (BLUP). Las ganancias genéticas directas e indirectas se estimaron con base en una intensidad de selección del 50%. Los parámetros de intensidad de color de la pulpa y el ángulo h° indicaron la posibilidad de selección indirecta de accesiones con un contenido de carotenoides total más alto. La adhesión a ABO22 mostró un mayor contenido de carotenoides totales en las condiciones de evaluación del experimento.

Palabras clave: Cucurbita moschata Duch; Colorimetría; Correlación; Variabilidad

INTRODUCTION

Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch) is considered to be an important source of carotenoids, which are the β-carotene precursors of vitamin A the most abundant with antioxidant activity (38). Carotenoids belong to the most commonly used group of natural dyes with colors ranging from yellow to red which are used in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries (29, 30). The use of natural dyes has increased because they add nutritional value to food and are healthy when compared with artificial dyes (25, 43).

Concern about the growing increase in malnutrition worldwide has led to the development of studies on food biofortification with the aim of improving the quality of agricultural products through conventional plant breeding. Food biofortification programs intend to reduce malnutrition and ensure greater food security through increased iron, zinc, and vitamin A levels in the diets of the poor (9, 33). Pumpkin, considered a traditional vegetable in the diet of the Brazilian population, especially in the Northeast, constitutes an important focus of study in the field of food biofortification (32, 42).

Pumpkin has a wide genetic variability across the regions of Brazil. It is cultivated mainly by family producers who select seeds over the year, which allows the identification of parents with important breeding characteristics. Thus, evaluation of the largest number of accessions could lead to the identification of superior genotypes in terms of nutritional characteristics, as well as other components that add value to the product (21).

The most commonly used methods for carotenoid quantification are the extraction, characterization, and identification of carotenoid pigments by spectrophotometry, mass spectrometry, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and the extremely accurate gas chromatography. However, these methods are expensive and time-consuming due to their use of many reagents. Therefore, alternatives for indirect quantification of carotenoids have been sought; in this context, colorimetry has been used because it is an instrumental method capable of measuring color characteristics in objects, in addition to being faster and less expensive when compared with other methods (6, 7).

When one considers that in the initial phase of breeding programs the evaluation of a large number of samples is common, the use of less expensive methodologies could result in greater germplasm coverage. Some studies involving pumpkin, tomato, and carrot have observed a high correlation between colorimetric methods and the content of carotenoids, demonstrating their great potential to replace spectrophotometric and chromatographic methods (4, 12, 23, 45).

On the other hand, the scientific literature dealing with the genus Cucurbita have reported variability of morphological and quality characteristics (5, 8, 34). Thus, the efficiency of the method must be proven in the germplasm that is intended to be used as the basis for a breeding program, because if there is no correlation between colorimetric values and carotenoid content, selection may be compromised. Therefore, using the methodology of mixed linear models, the objective of the present work was to verify the viability of indirect selection for assessment of the total content of carotenoids in pumpkin accessions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted at the experimental vegetable garden of the Departamento de Ciências Agronômicas e Florestais (DCAF), Universidade Federal Rural do SemiÁrido, Mossoró-RN (latitude 5° 11’ S, 37° 20’ long WGr and altitude 18 m) from September 2017 to February 2018. The soil of the experimental area is classified as Eutrophic Red Yellow Ultisol (14).

The experimental design comprised of complete randomized blocks with two replications and three plants per plot. The treatments consisted of 51 C. moschata Duch accessions from the DCAF/CCA/UFERSA Cucurbitaceae germplasm collection and a commercial C. maxima Duch cultivar obtained from a local wholesaler. The species C. maxima Duch was used as a new object in the study; it is commonly used in diversity studies with nearby species (15, 31). The spacing used was 4.00 x 3.00 m between rows and between plants, respectively.

The seeds were sown in 128-cell polystyrene trays with a commercial substrate in order to obtain the seedlings; transplanting took place when the seedlings had two to three definite leaves.

Tillage consisted of plowing and harrowing. The irrigation system used was a drip; an adjustable drip was placed in each plant with a flow rate of 18 liters/hour, providing the slide according to the phenological stage of the crop (3). Branch combing and weed control were performed manually.

After maturation, the fruits were harvested and sent to the postharvest laboratory located at the DCAF Centro de Pesquisas Vegetais do Semiárido (CPVSA). Then, pulp color and total carotenoid content were evaluated using one fruit per plant.

Pulp staining was determined at four equidistant points (fruit region around to the sun, fruit region exposed to the soil, fruit region exposed to the stalk, and fruit region exposed to inflorescence), followed by the arithmetic mean of staining. A Color Reader CR-400 Konica Minolta tri-stimulant manual colorimeter was used, with the following parameters: L*, luminosity; a*, contribution of red; and b*, the contribution of yellow. Chromaticity or saturation (C*) and hue (h°) were calculated based on the equations described by Itle and Kabelka (23).

The pulp color intensity was obtained from the visual analysis of the pulp of the fruits using grade descriptors, where fruits with light-colored pulp received grade 3, medium colored pulp, grade 5, and dark-colored pulp, grade 7. The total carotenoid content was measured using a UV Vis spectrophotometer FEMTO model 800 XI, according to the analytical methodology of separation and extraction of compounds with organic solvents of Rodriguez-Amaya and Kimura (2004) in duplicate.

Statistical analysis was performed according to statistical model 21 of the Selegen-REML/ BLUP software (36). The correlation between the variables was determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (16).

The selection gain for the variables was estimated using the formula GS = h2 mg x Ds, where h2mg is the average heritability of the genotype and Ds is the selection differential, Ds = Ms - Mo , where Ms is the selected average and Mo the original average. The percentage gain with selection (GS%) was obtained through ![]() (44). Selection was performed considering 50% of accessions, because it is an initial selection.

(44). Selection was performed considering 50% of accessions, because it is an initial selection.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

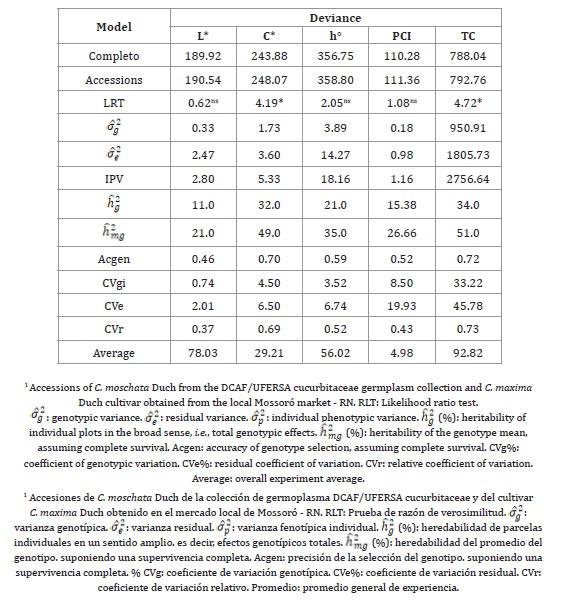

The effect of accessions was significant at the 5% probability level by the Chi-square test for chromaticity (C*) and total carotenoid (TC) characteristics. For the other characteristics, no significance was verified (table 1).

Table 1. Deviance analysis and estimates of variance components for pulp color characteristics: luminosity (L *), saturation (C*), hue (h°), pulp color intensity (PCI), and total carotenoids (TC) in accessions of Cucurbita sp1.

Tabla 1. Análisis de desviación y estimaciones de los componentes de varianza para las características del color de la pulpa: luminosidad (L*), saturación (C*), tonalidad (h°), intensidad del color de la pulpa (ICP) y carotenoides totales (CT) en las accesiones de Cucurbita sp1.

The average heritability of accessions obtained average magnitude values for the variables C* (49%) and TC (51%) (table 1). Heritability measures the level of correspondence between the phenotype value and the genetic value when heritability is high. Selection in the early generations of self-fertilization is effective; however, if its value is low, selection should be practiced only in the most advanced generations to determine the procedures and strategies to be adopted in the development stages of the cultivar (17, 39). For accuracy, high magnitude values were observed for C* (0.70) and TC (0.72) (table 2, page 16).

Table 2. Genetic correlation coefficient for pulp color characteristics: luminosity (L*), chromaticity (C*), hue (h°), pulp color intensity (PCI), and total carotenoids (TC) in accessions of Cucurbita sp.

Tabla 2. Coeficiente de correlación genética para las características del color de la pulpa: luminosidad (L*), cromaticidad (C*), tono (h°), intensidad del color de la pulpa (ICP) y carotenoides totales (CT) en las accesiones de Cucurbita sp.

**, *, and ns: significant at 1%, 5% probability, and non-significant by t-test, respectively.

**, * y ns: significativo al 1%, 5% de probabilidad y no significativo por la prueba t, respectivamente.

For the relative coefficient of variation, the variables presented values lower than one unit (table 1, page 15). Thus, the values found demonstrate that there was greater environmental influence for the variables, in accordance with Vencovsky (1987). Estimates of genetic parameters are important indicators for breeding programs, because they predict genetic values and maximize selection, where the significance of accession effects indicates the existence of genetic variability (11, 13, 28). According to the results of the parameters, it is evident that the adoption of breeding methods capable of returning considerable gains is necessary (1).

Recurrent selection is a methodology that allows for gains in traits with quantitative inheritance, resulting in a new population higher than the original, and providing better performance in selected individuals (19). Recurrent intrapopulation selection may be an appropriate methodology to obtain significant and consistent gains across generations. The procedure leads to improvements in genetic parameters, especially heritability, because it continuously and progressively improves population performance by increasing favorable allele frequencies of the characters under selection through the repeated selection and recombination cycles (10, 22).

The L* variable presented negative correlations of medium magnitude for the INTP (-0.54) and TC (-0.47) variables, where an increase in one variable meant a decrease in another (table 2). Thus, pumpkin fruits with lighter pulp (yellow) have higher L* values and lower PCI and TC values, and darker pulps (intense orange) have lower L* values and higher PCI and TC values.

C*, which is directly linked to the element concentration and represents a quantitative attribute for intensity (20), presented a positive mean correlation for PCI (0.53) and TC (0.58), and a high magnitude negative correlation to h° in the same variables (-0.85 and -0.82 respectively). Here, the increase in pulp saturation, C*, causes an increase for PCI and TC variables, and a reduction in h° angle, resulting in fruits with orange and very bright pulp which are more attractive to the consumer market (table 2). Aquino et al. (2016) studied ripe banana pulp and found that the h° index was negatively correlated with C* (-0.71), which is similar to the results of the current study.

The PCI variable showed a high positive correlation with TC of 0.71 (table 2), demonstrating that total carotenoid content is directly related to pulp color. The darker pulp indicts a higher content of carotenoid. Although visual assessment shows a higher variation in grades due to the subjectivity of the evaluator, it can be used with favorable results at the beginning of selection in breeding programs, where there are a large number of accessions to be evaluated. However, as selection advances, this method will have low efficiency.

The orange coloration of the pulp is a desirable component of quality in pumpkin fruits, and the angle h° is the variable that best defines this characteristic, where values above 30° and below 75° represent the orange color; the lower the values in this range, the more intense the pulp coloring (18, 27, 40). In the present study, evaluation of the angle h° was not verified by the chi-square test between the accessions, but showed high correlation with PCI (-0.85) and TC (-0.82), demonstrating a difference in the content of carotenoids between accessions.

The results found by Itle and Kabelka (2009) show a strong correlation between colorimetric values and carotenoid content, indicating that indirect selection for the high carotenoid index in pumpkin can be successful, easy to perform, and low cost.

The total carotenoid content in the different accessions ranged from 52.65 μg g-1 for ABO40 accession and 155.78 μg g-1 for ABO22 (table 3, page 17-18).

Table 3. Genotypic means of pumpkin accessions.

Tabla 3. Media genotípica de accesiones de calabaza.

Table 3 (cont.). Genotypic means of pumpkin accessions.

Tabla 3 (cont.). Media genotípica de accesiones de calabaza.

Amariz et al. (2009) studied C. moschata accessions belonging to the “Embrapa Semi-Árido” Cucurbitaceae Germplasm Active Bank and found variation from 21.3 to 78.5 μg g-1 in the total carotenoid content. When studying other accessions of “Embrapa Semi-Árido” Cucurbitaceae Germplasm Active Bank grown in Petrolina-PE (42), the same authors found total carotenoid contents ranging from 14.93 to 290.62 μg g-1. Variation in the results of different authors may occur due to the processes of preparation of raw materials, the different cultivars, the places of cultivation, and the ripening states of the fruit (26, 41, 45).

Taking into account the results obtained for the estimation of genetic parameters in the evaluated accessions and using a selection intensity of 50% because it was an initial selection, a selection of 26 accessions was performed with a prediction of genetic gains for the characters L*, C*, h°, PCI, and total carotenoid content (table 4, page 19).

Table 4. Estimation of indirect selection in pumpkin accessions for total carotenoids with a selection level of 50%.

Tabla 4. Estimación de la selección indirecta en accesiones de calabaza para carotenoides totales con un nivel de selección del 50%.

The L* variable presented the smallest gain with indirect selection at 4.76%. The h° variable presented the largest indirect selection gain of 6.76%, with a selected average of 105.12 μg g-1; this variable obtained the average closest to direct selection of total carotenoids from evaluation using a spectrophotometer (108.26 μg g-1) (table 4, page 19).

The selection gain estimate obtained a low percentage, which can be explained by the heritability with a maximum estimate of 51% (TC). Heritability represents the reliability with which the phenotypic value represents the genotypic value; therefore, characteristics with low heritability reflect a greater influence of the environment, reducing their discriminatory power (24, 35).

Direct selection of total carotenoids obtained the highest estimate for selection gain (8.48%) compared with other variables (table 4, page 19). From the selection obtained, it can be observed that the ten accessions with the highest total carotenoid contents may be the most promising for improvement, with averages above 110 μg g-1, whereas the ABO22 accession obtained the highest average of 155.78 μg g-1 (table 3, page 17-18). The accessions were collected in the cities of Rio do Fogo, Touros, Ipanguaçu, Assú, and some unknown sites. No relation was found between the accession collection site and the total carotenoid content because of the variability of the accessions collected.

CONCLUSIONS

The results associated with the parameters for the chromaticity and content of carotenoids present heritability and accuracy varying from medium to high magnitude, respectively, and obtained better results by using the recurrent selection method. Pulp color intensity parameters and h° angle indicate the possibility of indirect selection of accessions with a higher total carotenoid content. The ABO22 accession presented higher total carotenoid content under the evaluation conditions of the experiment.

1. Alves, J. C. S.; Peixoto, J. R.; Vieira, J. V.; Boiteux, L. S. 2006. Herdabilidade e correlações genotípicas entre caracteres de folhagem e sistema radicular em famílias de cenoura, cultivar Brasília. Horticultura Brasileira. 24: 363-367. DOI: 10.1590/S0102-05362006000300019. [ Links ]

2. Amariz, A.; Lima, M. A. C.; Borges, R. M.; Belém, S. F.; Passos, M. C. L. M. S.; Trindade, D. C. G.; Ribeiro, T. P. 2009. Caracterização da qualidade comercial e teor de carotenoides em acessos de abóbora. Horticultura Brasileira. 27: 541-547. [ Links ]

3. Amaro, G. B.; Pinheiro, J. B.; Lopes, J. F.; Carvalho, A. D. F.; Michereff Filho, M.; Vilela, N. J. 2014. Recomendações técnicas para o cultivo de abóbora híbrida do tipo japonesa. Brasília, DF: Embrapa Hortaliças. Circular técnica. 137 p. [ Links ]

4. Aquino, C. F.; Salomão, L. C. C.; Azevedo, A. M. 2016. Fenotipagem de alta eficiência para vitamina A em banana utilizando redes neurais artificiais e dados colorimétricos. Bragantia. 75: 268- 274. DOI: 10.1590/1678-4499.467. [ Links ]

5. Balkaya, A.; Özbakir, M.; Kurtar, E. S. 2010. The phenotypic diversity and fruit characterization of winter squash (Cucurbita maxima) populations from the Black Sea Region of Turkey. African Journal of Biotechnology. 9: 152-162. DOI: 10.5897/AJB09.1416. [ Links ]

6. Barrett, D. M.; Beaulieu, J. C.; Shewfelt, R. 2010. Color, flavor, texture and nutritional quality of fresh cut fruits and vegetables: desirable levels. Instrumental and sensory measurement. And the effects of processing. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 50: 369-389. DOI: 10.1080/10408391003626322. [ Links ]

7. Biehler, E.; Mayer, F.; Hoffmann, L.; Krause, E.; Bohn, T. 2010. Comparison of 3 spectrophotometric methods for carotenoid determination in frequently consumed fruits and vegetables. Journal of Food Science. 75: 55-61. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01417.x. [ Links ]

8. Blank, A. F.; Silva, T. B.; Matos, M. L.; Carvalho Filho, J. L. S.; Silva-Mann, R. 2013. Parâmetros genotípicos, fenotípicos e ambientais para caracteres morfológicos e agronômicos em abóbora. Horticultura Brasileira. 31: 106-111. DOI: 10.1590/S0102-05362013000100017. [ Links ]

9. Bouis, H. E.; Hotz, C.; Mcclafferty, B.; Meenakshi, J. V.; Pfeiffer, W. H. 2011. Biofortification: a new tool to reduce micronutrient malnutrition. Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 32: 31-40. DOI: 10.1177/15648265110321S105. [ Links ]

10. Cardoso, A. I. I. 2007. Seleção recorrente para produtividade e qualidade de frutos em abobrinha braquítica. Horticultura Brasileira. 25: 143-148. DOI: 10.1590/S0102- 05362007000200003. [ Links ]

11. Carloni, E.; López Colomba , E.; Ribotta, A.; Quiroga, M.; Tommasino, E.; Griffa, S.; Grunberg, K. 2018. Análisis de variabilidad genética en plantas regeneradas in vitro de buffelgrass mediante marcadores moleculares issr. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 50(2): 1-13. [ Links ]

12. Carvalho, W.; Fonseca, M. E. N.; Silva, H. R.; Boiteux, L. S.; Giordano, L. B. 2005. Estimativa indireta de teores de licopeno em frutos de genótipos de tomateiro via análise colorimétrica. Horticultura Brasileira. 232: 819-825. DOI: 10.1590/S0102-05362005000300026. [ Links ]

13. Cruz, C. D.; Regazzi, A. J.; Carneiro, P. C. S. 2012. Modelos biométricos aplicados ao melhoramento genético. Viçosa: UFV. Imprensa universitária. 514 p. [ Links ]

14. Embrapa. 2018. Sistema brasileiro de classificação de solos. Brasília. DF: Embrapa Solos. 567 p. [ Links ]

15. Endl, J.; Achigan-Dako, E. G.; Pandey, A. K.; Monforte, A. J.; Pico, B.; Schaefer, H. 2018. Repeated domestication of melon (Cucumis melo) in Africa and Asia and a new close relative from India. American Journal of Botany. 105: 1-10. DOI: 10.1002/ajb2.1172. [ Links ]

16. Excel. 2019. Microsoft office - Excel. Função Pearson. https://support.office.com/pt-br/article/ pearson-fun%C3%A7%C3%A3o-pearson-0c3e30fc-e5af-49c4-808a-3ef66e034c18. Accessed in: 21 nov. 2019. [ Links ]

17. Falconer, D. S.; Mackay, T. F. C. 1996. Introduction to quantitative genetics. Longman. New York. 464 p. DOI: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)81458-2. [ Links ]

18. Faustino, R. M. E. B. 2017. Predição de parâmetros genéticos e incremento da qualidade em frutos de progênies de aboboeira (Cucurbita moschata Duch.). 99 p. Thesis (PhD)-Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana. [ Links ]

19. Fehr, W. R. 1987. Principles of cultivar development: theory and technique. New York: MacMillan. 536 p. [ Links ]

20. Ferreira, M. D.; Spricigo, P. C. 2017. Colorimetria: princípios de aplicações na agricultura. In: Ferreira, M. D. (Org.). Instrumentação pós-colheita em frutas e hortaliças. Brasília. DF: Embrapa. 209-220 p. [ Links ]

21. Ferreira, M. A. J. F. 2008. Abóboras e morangas. In: Barbieri. R. L. Stumpf. E. R. T. (Eds.). Origem e evolução de plantas cultivadas. Embrapa Informações Tecnológicas. 59-88 p. [ Links ]

22. Hallauer, A. R. 1992. Recurrent selection in maize. Advanced Agronomy. 102: 115-179. DOI: 10.1002/9780470650363.ch6. [ Links ]

23. Itle, R. A.; Kabelka, E. A. 2009. Correlation between L* a* b* color space values and carotenoid content in pumpkins and squash (Cucurbita spp.). HortScience. 44: 633-637. DOI: 10.21273/HORTSCI.44.3.633. [ Links ]

24. Ivoglo, M. G.; Fazuoli, L. C.; Oliveira, A. C. B.; Gallo, P. B.; Mistro, J. C.; Silvarolla, M. B.; Toma-Braghini, M. 2008. Divergência genética entre progênies de café robusta. Bragantia. 67: 823-83. DOI: 10.1590/S0006-87052008000400003. [ Links ]

25. Kayodé, A. P. P.; Bara, C. A.; Dalodé-Vieira, G.; Linnemann, A. R.; Nout, M. J. R. 2012. Extraction of antioxidant pigments from dye sorghum leaf sheaths. Food Science and Technology. 46: 49-55. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.11.003. [ Links ]

26. Lorello, I. M.; García Lampasona, S. C.; Peralta, I. E. 2020. Genetic diversity of squash landraces (Cucurbita maxima) collected in Andean Valleys of Argentina. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 52(1): 293-313. [ Links ]

27. Luna Guevara, M. L.; Ochoa Velasco, C. E.; Hernández Carranza, P.; Contreras Cortes, L. E. U.; Luna Guevara , J. J. 2018. Composición, propiedades físico-químicas y capacidad antioxidante del fruto Renealmia alpinia (Rottb.) Maas. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 50(2): 377-385. [ Links ]

28. Maia, M. C. C.; Resende, M. D. V.; Paiva, J. R.; Cavalcanti, J. J. V.; Barros, L. M. B. 2009. Seleção simultânea para produção, adaptabilidade e estabilidade genotípicas em clones de cajueiro, via modelos mistos. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical. 39: 43-50. [ Links ]

29. Martín, A.; Mattea, F.; Gutiérrez, L.; Miguel, F.; Cocero, M. J. 2007. Co-precipitation of carotenoids and bio-polymers with the supercritical anti-solvent process. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 41: 138-147. DOI: 10.1016/j.supflu.2006.08.009. [ Links ]

30. Martins, N.; Roriz, C. L.; Morales, P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I. C. F. R. 2016. Food colorants: Challenges. opportunities and current desires of agroindustries to ensure consumer expectations and regulatory practices. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 52: 1-15. DOI: 10.1016/j. tifs.2016.03.009. [ Links ]

31. Morales, R. G. F.; Resende, J. T. V.; Faria, M. V.; Silva, P. R.; Figueiredo, A. S. T.; Carminatti, R. 2011. Divergência genética em cultivares de morangueiro, baseada em caracteres morfoagronômicos. Revista Ceres. 58: 323-329. DOI: 10.1590/S0034- 737X2011000300012. [ Links ]

32. Moreira, L. A. S.; Carvalho, L. M. J.; Cardoso, F. S. S. N.; Ortiz, G. M. D.; Finco, F. D. B. A. Carvalho, J. L. V. 2019. Different cooking styles enhance antioxidant properties and carotenoids of biofortified pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch) genotypes. Food Science and Technology. 3: 1-5. DOI: 10.1590/fst.39818. [ Links ]

33. Moura, F. F.; Palmer, A. C.; Finkelstein, J. L.; Haas, J. D.; Murray-Kolb, L. E.; Wenger, M. J.; Birol, E.; Boy, E.; Peña-Rosas, J. P. 2014. Are biofortified staple food crops improving vitamin A and iron status in women and children? New evidence from efficacy trials. Advances in nutrition. 5: 568-570. DOI: 10.3945/an.114.006627. [ Links ]

34. Oliveira, R. L.; Gonçalves, L. S. A.; Rodrigues, R.; Baba, V. Y.; Sudré, C. P.; Santos, M. H.; Aranha, F. M. 2016. Genetic divergence among pumpkin landraces. Semina: Ciências Agrárias. 37: 547- 556. DOI: 10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n2p547. [ Links ]

35. Oliveira de Souza, N.; Silva Alves, R.; Teodoro, P. E.; Silva, L. A.; Dessaune Tardin, F.; Baldoni Tardin, A.; Vilela de Resende, M. D.; Lopes Bhering, L. 2019. Single- and multiple-trait BLUP in genetic selection of parents and hybrids of grain sorghum. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. Mendoza. Argentina. 51(2): 1-12. [ Links ]

36. Resende, M. D. V. 2007. Software SELEGEN-REML/BLUP: sistema estatístico e seleção genética computadorizada via modelos lineares mistos. Colombo: EMBRAPA Florestas. 359 p. [ Links ]

37. Rodriguez-Amaya, D. B.; Kimura, M. 2004. HarvestPlus handbook for carotenoid analysis. Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute. [ Links ]

38. Rodriguez-Amaya, D. B.; Kimura, M.; Godoy, H. T.; Amaya-Farfan, J. 2008. Updated Brazilian database on food carotenoids: Factors affecting carotenoids composition. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 21: 445-463. DOI: 10.1016/j.jfca.2008.04.001. [ Links ]

39. Ruiz, E.; Sigarroa, A.; Cruz, J. A. 2004. Analisis dialelico del rendimiento y sus principales componentes en variedades de calabaza (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) I. Tabla dialelica de griffing. Revista Biología. 18: 65-73. [ Links ]

40. Sasaki, F. F. C.; Aguila, J. S.; Gallo, C. R. 2014. Jacomino AP and Kluge RA Physiological. Qualitative and microbiological changes of minimally processed squash stored at different temperatures. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologia Poscosecha. 15: 210-220. [ Links ]

41. Shi, J.; Yi, C.; Ye, X.; Xue, S.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, D. 2010. Effects of supercritical CO2 fluid parameters on chemical composition and yeld of carotenoids extracted from pumpkin. Food Science and Technology. 43: 39-44. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.07.003. [ Links ]

42. Souza, C. O.; Menezes, J. D. S.; Ramos Neto, D. C.; Assis, J. G. A.; Silva, S. R.; Druzian, J. I. 2012. Carotenoides totais e vitamina A de cucurbitáceas do Banco Ativo de Germoplasma da Embrapa Semiárido. Ciência Rural. 42: 926-933. DOI: 10.1590/S0103-84782012005000024. [ Links ]

43. Valduga, E.; Tatsch, P. O.; Tiggemann, L.; Treichel, H.; Toniazzo, G.; Zeni, J.; Di Luccio, M.; Fúrigo Júnior, A. 2009. Produção de carotenoides: microrganismos como fonte de pigmentos naturais. Química Nova. 32: 2429-2436. DOI: 10.1590/S0100-40422009000900036. [ Links ]

44. Vencovsky, R. 1987. Herança quantitativa. In: Paterniani, E.; Viegas, G.P. (ed). Melhoramento e produção do milho. Campinas: Fundação Cargill. 137-214 p. [ Links ]

45. Veronezi, C. M.; Jorge, N. 2011. Carotenoides em abóboras. Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos. Curitiba. 29 p. [ Links ]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To “Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001” for financial support.