Introduction

The introduction of exotic species represents a threat to the biodiversity of ecosystems and a serious problem for agriculture 13,25.

The red palm mite, Raoiella indica Hirst 1924 (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) is an exotic pest native to India 30. In the American continent, it was first detected in 2004 in the Caribbean, in the Island of Martinique 9. Since then, it spread throughout most of the islands of the region 9,24. In 2008, R. indica appeared in Venezuela 36 and Florida, USA, 23; in 2009 it was recorded in Mexico 17.

The coconut palm (Cocos nucifera L.) is the main host of R. indica, although its host list has almost 70 species 6, R. indica causes damage to coconut palms by inserting its chelicerae through stomatal openings in order to feed on the cellular content of the mesophyll 19. The greatest damage has been observed during the nursery phase, even leading to the death of plants. In adult plants, the damages are more evident in mature leaves, which turn yellowish and can dry up completely, reducing the plant’s photosynthetic rate and causing flower abortion, which affects the coconut yield 24,29.

The control of R. indica has been carried out mainly through the use of chemical products, but given the height of some of its hosts and its presence in areas where this type of control is problematic, such as tourist and residential areas, the use of natural enemies can be considered a promising alternative 5,11,12.

Chrysopidae species are excellent predators that feed on a wide variety of phytophagous insects and mites that are found on plant leaves 1,10,34. Peña et al. (2009) reported species of Chrysopidae feeding on R. indica in Trinidad and Tobago, Puerto Rico and Florida, United States. Carrillo et al. (2011) identified two species of Chrysopidae, including Ceraeochrysa claveri (Navás, 1911) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), that fed on R. indica. Contreras-Bermúndez et al. (2017) also reported five species of Chrysopidae, including C. claveri, that naturally fed on R. indica in the area of Tecomán, Colima, Mexico.

Ceraeochrysa claveri is an important predator of phytophagous pests in many Neotropical agroecosystems and because of a broad prey range, high voracity, high search capacity and short developmental time, C. claveri can be considered an efficient biological control agent 1.

Based on the information presented above and given the little information available on the biology and predatory activity of Chrysopidae on phytophagous mites, the present study aimed to study the predatory capacity, larval development and longevity of adults of C. claveri when having R. indica as its main prey. The information obtained would be useful for the integrated management of this pest.

Materials and methods

A C. claveri colony was established using the method developed by the Entomophagous Insects Department of the Centro Nacional de Referencia de Control Biológico (IE-CNRCB) 22. The insects were collected in a commercial coconut palm crop located on the malecon of Real-Pascuales, Municipality of Tecomán, Colima, Mexico (18°50’56.43’’ N; 103°57’15.08’’ W). The mites were collected in a commercial coconut palm crop located in the Amela Lagoon, of the same municipality (18°49’39.60’’ N; 103°47’08.83’’ W).

Prior to the study, C. claveri was identified using the keys of Tauber et al. (2000). The identity of R. indica was confirmed by molecular analysis (genomic DNA extraction using the HotSHOT method) at the Molecular Biology Laboratory (MBL) of the CNRCB 32,35. The specimens were deposited in the Entomophagous Insect Collection (CIE) of the CNRCB.

The evaluations were performed on the F0 generation of C. claveri in a laboratory of the IE-CNRCB located in the city of Tecomán, Colima, Mexico (18°55’37.62’’ N and 103°53’ 01.45’’ W; 45 m a. s. l.) under the following conditions: 25 ± 2°C, 60-70% RH and 14:10 h LD.

Predation capacity

The predation capacity of C. claveri was evaluated using the sand paper method, which consisted of a Petri dish (5 cm in diameter) with a disk of sterile wet filter paper at the bottom, covered by a disk of banana leaf (5 cm in diameter), on top of which were placed 50 individuals of R. indica. An hour later, a predator was introduced to each experimental arena. Before starting the experiment, the larvae were fasted for 12 h. The first larval instar was used 24 h after emerging from the egg; the second and third instars were used 24 h after the immediately previous instar change. The number of individuals consumed in a period of 5 h was determined. The individuals consumed by the predator were not replaced during the experiment. Ten repetitions were performed in a breeding chamber under the environmental conditions mentioned above.

The number of individuals consumed by each instar was analysed by ANOVA. When significant differences were observed, a Tukey’s multiple comparison test (α = 0.05) was applied 28.

Larval development

Two larval development assays were conducted. The first consisted of a cohort of 129 larvae with 24 h of having emerged, which were placed individually in Petri dishes whose bottom was covered with a 5-cm-diameter banana leaf. The first and second instars were fed with 50 individuals of R. indica; the third with 100. The second assay consisted of a cohort of 90 larvae with 24 h of having emerged, which were fed using the method described above. To evaluate the effect of diet on larval development, 100 eggs of Sitotroga cerealella (Oliver, 1789) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) were added to larva 3 in the second trial. Every 24 h observations were made and the food was changed until the pupae were obtained. The presence of larval exuviae was taken into account to estimate the duration of each biological stage in days; survival was also recorded. The pupa was defined by the presence of the cocoon and culminated in the emergence of the adult.

The emerging adults were individually transferred to Styrofoam cups of 8 cm in diameter and 6 cm in height to determine their longevity. To facilitate aeration and to prevent insects from escaping, a 4-cm-diameter opening was made in the lid and covered with organza cloth. A 1.5-cm-diameter opening was made on the lower side of the cup; it was plugged with cotton and moistened daily to supply water to the adult. To feed the adults, a piece of 1.5 X 2 cm bond paper impregnated in the artificial diet (honey, brewer’s yeast, pollen, ascorbic acid and spirulina) was placed inside the cup every third day 22.

The data were recorded per day and the survival and development time of the biological stages were evaluated. It allowed to determine the mortality rate (qx = Death rate [dx/lx]) and life expectancy (ex = Life expectancy [Tx/lx]), where lx = proportion of survivors at the beginning of each stage (Nx/N0), dx = number of deaths between stages lx and lx + 1, and Tx = Time left to live until extinction (inverse summation lx). The sex ratio was determined by the formula rs = number of females/number of females + number of males 31.

Results and discussion

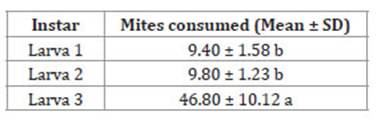

Predation capacity: the statistical analysis showed a significant (α = 0.05) difference between instars (F value = 32.99; P < 0.0001) indicating a greater consumption by third instar larvae (Table 1).

Table 1: Tabla 1: Average consumption of Raoiella indica by the F0 generation of Ceraeochrysa claveri after 5 h of evaluation (25 ± 2°C, 60-70% RH, 14:10 LD). Consumo promedio de la generación F0 de Ceraeochrysa claveri alimentada con Raoiella indica a las 5 h de evaluación (25 ± 2°C, 60 - 70 % HR, 14:10 LO).

* Means with the same letter are statistically the same.

* Medias con la misma letra estadísticamente son iguales.

Although species of the family Chrysopidae have been reported feeding on mites, we found no previous study on predation capacity against mites. For this reason, the data obtained in the present study was compared with other species and other preys. The greatest voracity was recorded in the third instar larvae (larva 3). Guarín (2003) and Velásquez (2004) mentioned that the third larval instar of Chrysopidae species shows a voracious appetite, as well as a high degree of cannibalism. In agreement with it, Ferreira-Almeida et al. (2009) reported that third instar larvae of C. claveri consumed 80% of preys when fed with Plutella xylostella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Similarly, when evaluating Ceraeochrysa cincta (Schneider) and C. valida Banks (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) fed with Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liividae), Pacheco-Rueda et al. (2015) and Palomares-Pérez et al. (2016) concluded that third instar larvae are the most voracious. Probably, the greater voracity of third instar larvae is a behaviour associated with the larger size of these larvae 26 and the need to accumulate and store molecules, such as lipids, proteins and carbohydrates, which will be used for keeping the insect alive during the diapause and for nutrition afterwards.

Larval development. Table 2 (page 229), shows the data on larval development.

Table 2: Tabla 2: Larval development in days of the F0 generation of Ceraeochrysa claveri fed with Raoiella indica and with eggs of Sitotroga cerealella at 25 ± 2°C, 60-70% RH and 14:10 h LD. Desarrollo larval en días de la generación F0 de Ceraeochrysa claveri alimentado con Raoiella indica y con huevo de Sitotroga cerealella a 25 ± 2°C, 60-70% HR y 14:10 h. LO.

n = Individuals evaluated; SD = Standard deviation; qx= Mortality rate; ex = Life expectancy.

n=Individuos evaluados; SD=Desviación estándar; qx =Tasa de mortalidad; ex = Esperanza de vida.

It shows that all individuals in the third instar died when feeding only on R. indica (Table 2a, page 229). When eggs of S. cerealella were added to the diet of third instar larvae of C. claveri they were able to surpass the larval and pupal stages and reach adulthood in 35.4 ± 2.8 d, with a survival rate of 13.3% (Table 2b, page 229).

Table 2 (page 229) shows that the duration of the first instar (Larva 1) is similar to that of the second instar (Larva 2), unlike the third instar (Larva 3), which lasts longer but is shortened when S. cerealella eggs are added to the diet (Table 2b, page 229). This may be due to the nutritional quality provided by S. cerealella eggs compared to R. indica. Soffiantini-Lira and De Luna-Batista (2006) mentioned that a shorter life cycle is a consequence of good nutrition.

Ferreira-Almeida et al. (2009) reported shorter periods for the three larval instars of C. claveri when fed with different preys; they concluded that this was due to good nutrition. Santa-Cecília et al. (1997) evaluated the performance of Ceraeochrysa cubana (Hagen) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) with different preys and found that the quality of food ingested by larvae affected their biological development.

The mortality rate was high in larva 2, and in larva 3, total death occurred when the three larval instars were fed only with R. indica. Possibly the size and number of prey offered did not provide the necessary amounts of nutrients to allow the full development of the larvae, the good formation of the pupae and as a result, give rise to adults. When adding S. cerealella eggs to the diet of the larva 3, 12 individuals of 90 reached the adult state, living on average 6.7 ± 4.9 d (Table 2b), this time was not sufficient to exceed the period of pre-oviposition (10.6 ± 0.51 days) 8 as a consequence, there was no offspring. The data suggest that C. claveri can take R. indica as an secundary prey since feeding on this mite alone it could not complete its cycle, unlike the results obtained by Carrillo et al. (2011), where they found that C. claveri complete its cycle, although adults don’t get to reproduce.

The results obtained in the present study indicate that increasing the quality of food in the diet of the third instar larvae provides sufficient nutrients to complete the larval and pupal stage, but requires better feeding, possibly during the first two instars, for the adult to develop fully.

Although the sex ratio (rs = 0.42) indicates a greater number of males, it is close to the 50/50 ratio reported by Núñez (1988). However, a biased sex ratio to males may favor fertility by increasing the possibility of female encounters with virgin males, which would result in increased egg production 16.

The type of feeding during the larval period is crucial for preimaginal development and can affect the time of development, survival, fertility and longevity in the adult stage 3,15. Santa-Cecília et al. (1997), Auad et al. (2001) and Ferreira-Almeida et al. (2009) mentioned that the quality of the food ingested by larvae of C. cincta, C. cubana and C. claveri can interfere with the development and survival of adults.

Conclusions

According to the information obtained, C. claveri is unable to complete its larval development using R. indica as the only prey and therefore, this mite can be considered as a secondary prey.

Its high voracity, especially in the third stage, demonstrates its potential to be included in a biological control program for R. indica.