Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is the most common greenhouse-grown vegetable, greatly demanded worldwide. The intensive tomato greenhouse production system employs indeterminate variety types with low planting densities ranging from two to three plants per square meter. Side shoots are often pruned, leaving a single stem that reaches more than seven meters long, achieving 15 or more bunches per plant in a single season per year at harvest 3. This production system is relatively new in Mexico and has contributed to the increase in cultivated area, productivity, profitability and quality 20,21.

Plant density and other management practices, such as pruning, side shoot removal and plant staking, are considered important in intensive production systems 6,24. Pruning reduces plant height and the crop-growing period, and induces the plant to develop better quality fruit in terms of size and yield 5,18,29,36,37. Side shoot removal reduces internal competition for water, nutrients and assimilates, and the string trellis method supports the plant and improves canopy illumination 24. However, the manipulation of plant density optimizes the intercepted radiation 28,37. A high plant density increases the number of small fruit 20.

The leaf area index (LAI) is an important variable for studying crop growth and development. In addition, it is the basis for estimating crop water and nutrient requirements, bioenergy efficiency, and potential crop damage. There is a close relationship between LAI and solar radiation interception, which is associated with photosynthesis and transpiration processes, both of which are strongly linked to biomass accumulation and productivity. Therefore, LAI is a variable used to quantify crop growth and yield 14,17. The electromagnetic spectrum region of greatest interest in agriculture is photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), which has wavelengths between 400-700 nm. It is important to know the spatial and temporal distribution of PAR interception by crops, as it is the basis for the analysis of biological processes 13.

Direct LAI determinations are often destructive and require instruments to penetrate the leaf surface 40. As a variant of this method, Rodríguez (2000) used digital photographs and image interpretation techniques to measure leaf area and determine LAI in potato crops. However, there are indirect, non-destructive methods that allow for a quick in-field determination of the relationship between radiation penetration and canopy structure.

To measure PAR, devices such as the ceptometer have often been used. This device measures photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), defined as the amount of photosynthetically active photons falling on a given surface per unit area per unit of time, and is expressed in μmol m-2 s -1. De La Casa et al. (2008) obtained a correlation of R2 = 0.86 when comparing the LAI measured by the ceptometer with measurements obtained from digital photographs of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) crops. Mendoza-Pérez et al. (2017) obtained promising results when comparing the LAI values produced by the ceptometer as compared to direct measurements obtained using an LI-3100C leaf integrator on Poblano pepper (Capsicum annuum L.).

The development of many plant species and organisms is mainly controlled by temperature (thermal time). The basic concept of thermal time is that many phenological and growth crop processes proceed in direct relation to the accumulated temperature experienced by the crop. Below a base temperature, no thermal time accumulates and crop development ceases. Above an optimum temperature, crop development is not enhanced; presumably, between these temperature thresholds, the plant must accumulate a certain amount of thermal time to complete development 22,32.

There is a clear need to identify the growth and development stages of tomato crops in terms of irrigation and fertilization planning in a controlled environment. LAI, as influenced by the number of stems per plant, is one of the agronomic management variables associated with productivity. The greater the number of stems per plant, the greater the leaf area. However, the overall production (fruit quantity and quality) can be affected, as reported by Mendoza-Pérez et al. (2017). Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the LAI of tomato with an indirect method (ceptometer), compare it with a direct method, and analyze the relationship between LAI and the biomass, yield and quality of fruit grown under greenhouse conditions.

Materials and methods

Description of the experiment

The experiment was carried out in a greenhouse located on the Graduate College, Montecillo Campus, (19°28’05” North latitude and 98°54’31” West longitude, at 2244 m a. s. l.). Saladette-type tomato variety ‘Cid’ was planted. Seeding occurred on March 5th, transplanting on April 20th and harvesting finished on September 20th, 2015. Plantation frame was 40 cm x 40 cm. Seedlings were transplanted in 35 × 35 cm black polyethylene bags using tezontle (red volcanic scoria) as the substrate.

Treatments consisted of three management conditions as a function of stems per plant: T1 = one stem, T2 = two stems and T3 = three stems per plant. The main stem in T1 was left to grow. T2 and T3 maintained the main stem with one and two secondary stems, respectively. The area of each treatment was 53 m2. Each main treatment was established in plots with two beds 20 m long and 1.35 m apart, resulting in a crop density of 3 plant m-2. A split-plot randomized complete block experimental design was used, with four replicates.

The drip irrigation system employed on-surface driplines, 16 mm in diameter with self-compensating drippers of 4 L h−1 at 40 cm apart and an operating pressure of 0.7 kg cm-2. Irrigation with Steiner’s nutrient solution was applied throughout the season. The flow rate (Q) was 0.155 L per plant for the first 30 days after transplant (DAT), which corresponded to the initial stage, while 0.462 L and 0.891 L per plant were applied in vegetative and reproductive stages, respectively. At maximum demand (production), the flow rate increased to 1.650 L per plant.

Estimate of LAI using a ceptometer

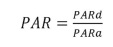

The LAI measurement was performed with an AccuPAR LP-80 ceptometer (PAR/LAI Ceptometer, Decagon Devices, Pullman, Washington, USA), which estimates PAR under field conditions and consists of a 1-m long bar with 80 sensors divided into eight segments. Readings were taken every 8 days starting at 20 days after transplant (date on which the division of the number of stems began) until the harvest of the tenth cluster of fruit (September 20th, 2015). Measurements were made above and below the canopy, with six replications per treatment. The intercepted PAR values were estimated from two positional levels of radiation, one above the foliage to obtain the incident PAR (PARa) and the other below the foliage to obtain the PAR reaching the ground (PARd) in μmol m-2 s-1 (Equation 1).

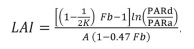

Once the PAR was obtained, it was combined with other variables, such as leaf angle factor, solar zenith angle and radiation extinction coefficient. Finally, an adjustment was made to estimate the LAI of the plant according to Equation 2 proposed by Campbell and Norman (1989).

where:

K = the radiation extinction coefficient that considers a spherical angular distribution parameter k = 1

Fb = the fraction of direct radiation with respect to global solar radiation (0.25)

A = the absorption coefficient of the canopy that is equal to 0.86 (Campbell and Norman, 1989).

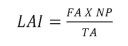

Ceptometer readings were taken only under clear sky conditions during the period of maximum solar insolation (noon). Thus, the zenith angle was as low as possible, and factor Fb corresponded to high fractions of direct solar radiation that made it possible to homogenize data. LAI measurements were made with the destructive method (extracting the plant, separating the leaves and measuring the leaf area) with the electronic leaf area integrator (Area Meter Model LI-3100, Decagon Device, Inc. Lincoln, Nebraska, USA) to compare that data with that obtained from the ceptometer. In addition, plant LAI was calculated using Equation 3, as described by Reis et al. (2013).

where:

LAI = leaf area index (m2 m-2)

FA = the average foliar area of three plants (m2)

NP = the number of plants per m2 and TA is the total area considered to be 1m2

Description of variables

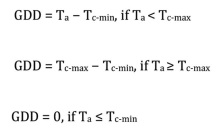

Growing degree days (GDD) for each day were calculated using Equation 4, as proposed by Ojeda-Bustamante et al. (2004).

where:

T a = daily air temperature

T c-max and T c-min = maximum and minimum air temperature. The temperature range for tomato growth is 6 and 29°C (Iglesias, 2015).

The cumulative GDD values for n days are expressed as follows:

where:

i = the number of days elapsed from an initial day of interest, usually the transplant date or the first day of a stage

GDD = growing degree day for each day

For dry weight determination, plant stems, roots, leaves and fruit were weighed fresh and then placed on a forced air oven at 70°C for 72 hours for complete dehydration. Finally, all samples were weighed using a digital scale 5000p model with 0.001 g resolution.

To estimate yield, eight plants were selected per treatment. Plant height and the number and size of fruit were also evaluated. Classification of fruit sizes was made with the following categories (large, medium, small and tiny) based on the equatorial diameter using the fruit diameter Mexican standard NMX-FF-009-1982.

Results and discussion

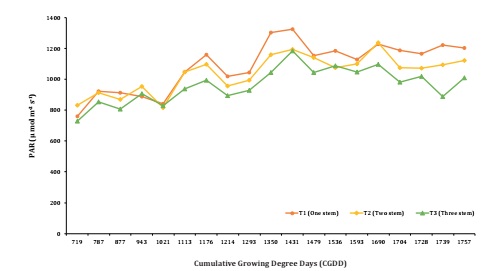

Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR)

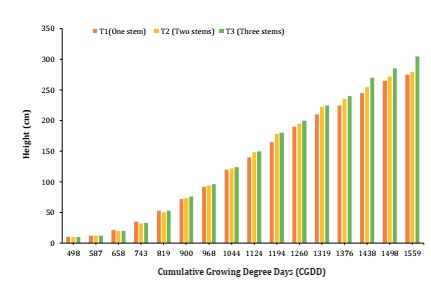

Photosynthetically active radiation intercepted in the canopy at the initial stage was approximately 900 μ mol m-2 s-1 in all treatments. Plant leaf area and, consequently, biomass increased over time. The maximum amount of radiation intercepted was 1300 μ mol m-2 s-1, which coincided with the maximum LAI at flowering (seventh floral cluster and 1431 CGDD). Afterwards, it started to decrease (from June through September), coinciding with the rainy months in the study area (Figure 1).

Figura 1: Radiación fotosintéticamente activa interceptada en el dosel de la planta durante todo el ciclo de desarrollo del cultivo.

Mendoza-Pérez et al. (2017) obtained similar PAR trends in greenhouse-cultivated Poblano pepper. In addition, García-Enciso et al. (2014) obtained similar PAR trends in the production and quality of greenhouse-grown tomato fruit.

Leaf area index (LAI)

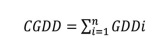

T3 had the highest LAI, with the highest value of 6.16 at flowering (1431 CGDD), after which it decreased. At 1113 CGDD, LAI differed among treatments due to differences in the number of stems. Figure 2 shows the LAI values obtained with the ceptometer and the destructive method.

The highest value of LAI was found at 1431 CGDD with 3.69, 5.27 and 6.16 m2.m−2 for T1, T2 and T3, respectively.

LAI started to decrease once maximum growth and development were achieved due to leaf senescence. These results agreed with those reported in a tomato trial by Vargas (2012), who found a LAI of 4.0 m2.m−2 for a mixture of tezontle and sawdust (20:80 ratio), a LAI of 5.2 m2 m-2 (30:70 ratio) with the same mixture and an LAI of 6.2 m2 m-2 using tezontle only.

Mendoza-Pérez et al. (2017) obtained similar results in the cultivation of Poblano pepper as a function of the number of stems per plant grown under greenhouse conditions. Rojas (2015) evaluated the impact on tomato development and yield at different percentages of PAR block during winter, obtaining a LAI of 3000, 2100, 2100, 2000 and 1750 cm2 for blocks of 50, 35, 60, 25 and 75%, respectively.

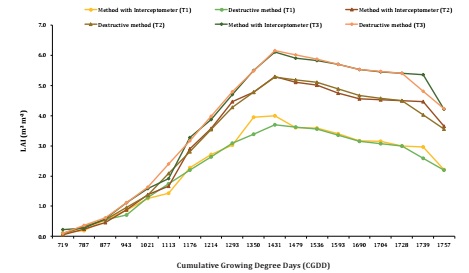

Coefficient of determination

The data showed a linear relationship in both methods (measured and estimated), with similar slopes (angular coefficient). The R2 values were 0.98, 0.99 and 0.99 for T1, T2 and T3, respectively (P < 0.01). The dispersion of LAI data explained by direct determination was the result of the effects of the measurements of a 1m2 area as compared with measurements in more replicates obtained with the ceptometer (Figure 3, page 63).

These data were similar to those reported by De la Casa et al. (2012) in potato, achieving R2 values of 0.80, and to those of Mendoza-Pérez et al. (2017) in Poblano pepper, attaining R2 values of 0.82 for treatments with two stems, 0.94 for treatments with three stems and 0.99 without pruning.

Dry matter

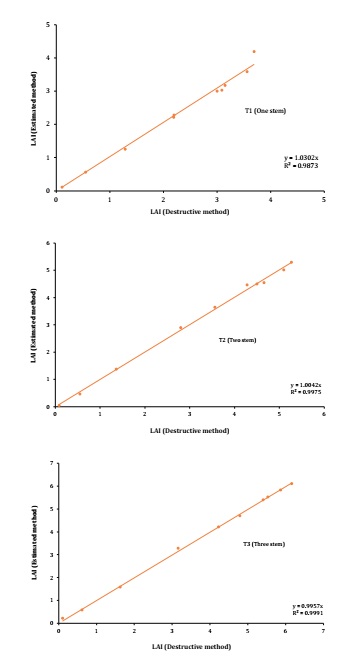

The distribution of dry matter among different plant organs plays a fundamental role in crop production, since growth is achieved by the capacity of the plant to accumulate biomass in the organs 20. Figure 4 shows the partition of dry matter in different plant organs (leaf, stem, fruit, root and flower), attained at 1167 CGDD.

These results are similar to those reported by Betancourt and Pierre (2013), Hernández et al. (2009) and Gandica and Peña (2015). Therefore, there was an increasing accumulation of dry matter in the aerial part where the fruit contributed much of this content in the full production phase, as shown by Gandica and Peña (2015). This variable had a direct relationship with the LAI (the higher the biomass, the higher the LAI). However, both fruit yield and quality were affected because of processes within the plant. In the same way, Villegas et al. (2004) found similar trends in tomato under greenhouse conditions 12.

Plant height

Plant height was low from transplant to 658 CGDD. Between 743 and 819C CGDD, it increased markedly until reaching 275, 280 and 305 cm for T1, T2 and T3, respectively (Figure 5, page 66).

The shoot apex of the plant was cut once the 10 clusters were accumulated.

Growth dynamics followed a sigmoid-like curve. The curve suggested exponential growth from 743 CGDD in all treatments. At 900 CGDD, the T3 growth rate accelerated, resulting in more stems and leaves that were responsible for intercepting light for photosynthesis. This performance was similar to that reported by Núñez-Ramírez et al. (2012).

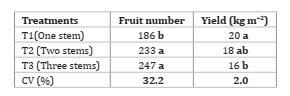

Total fruit number per plant

Table 1 shows the total fruit number obtained in each treatment.

Tabla 1: Número total y rendimiento de frutos en cada tratamiento.

CV = coefficient of variation (%).

CV = Coeficiente de variación (%).

The values were 186, 234 and 247 fruit per m−2 for T1, T2 and T3, respectively. Núñez-Ramírez et al. (2017) reported similar results for fruit number, quality and final yield as influenced by nitrogen fertilization. The values found in this work show that T2 and T3 had plants with a higher fruit number compared to T1.

Yield per plant

The final yield obtained was 20, 18 and 16 kg m-2 for T1, T2 and T3, respectively. These data coincide with those reported by Corella et al. (2013), who obtained yields of 23.43 and 18.55 kg m-2 for the same crop under similar conditions. Finally, T3 had the lowest yield (16 kg m-2). However, no literature was found that considered the yield and quality of three-stem tomato plants. Furthermore, De la Rosa-Rodríguez et al. (2016) obtained similar results when comparing tomato production and quality in open and closed hydroponic systems. They achieved yields of 17.5 and 16.9 kg m-2 with a density of 4 plants m-2.

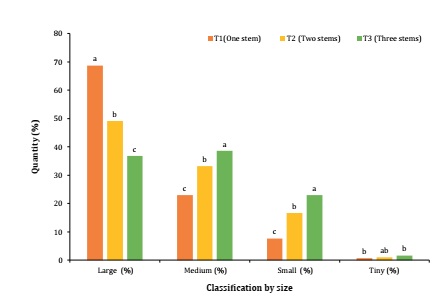

Fruit size classification

Figure 6 (page 67) shows that the number of stems per plant can strongly affect the final fruit size.

T1 had approximately 69, 23, 8 and 1% of the fruit classified as large, medium, small and tiny, respectively.

These results were similar to those reported by Rodríguez et al. (2008), who found that 60, 20, 10 and 10% corresponded to extra size, first and second class as well as loss, respectively.

For T2, approximately 49, 33, 17 and 1% were classified as large, medium, small and tiny, respectively. These results were similar to those reported by Quintana-Baquero et al. (2010), who found that 9, 52, 27, 11 and 1% corresponded to extra size, first, second, third and fourth classes, respectively. Finally, in T3, the percentages of large, medium, small and tiny were 37, 39, 23 and 1%, respectively. However, T3 produced more medium-sized and small fruit compared to T1 and T2, respectively.

Conclusions

Estimation of the LAI of tomato using a ceptometer proved to be a fast, useful and statistically reliable method. LAI was strongly correlated with yield by increasing the fruit number per plant. It also increased the amount of photosynthetically active radiation intercepted by the canopy, which favored photosynthetic efficiency per unit area. This process can be mainly attributed to a higher concentration of chlorophyll per unit leaf area.

The number of stems per plant was shown to increase the LAI, dry matter accumulation, plant height and fruit number. However, fruit size (quality) decreased. Further studies with a higher nutrient concentration should be conducted, since it could be the key to maximizing the yield potential of two-stem plants.