Introduction

Maize constitutes an essential nutrient for the human diet. Despite a low protein content compared to other vegetables, it provides, on average, 39% of overall protein intake, and 59% of human energy requirements 38.

Mexico is the largest market for maize, consuming 11% of world production 29. However, the low-yielding domestic production does not meet the growing demand, and importation reaches approximately 11.3 and 0.145 million tons of yellow and white maize, respectively 36. Hence, there is an evident need to explore technological alternatives for environmentally friendly production and increasing yields.

The indiscriminate use of ammonia fertilizers on some bedrock types of soil, causes serious acidification problems. Soils in the Frailesca region of Chiapas are undergoing an acidification process 11 and consequent increasing toxic aluminium contents in maize plants, particularly at pH levels below 5.0 6. Faced with such a situation, finding alternatives entailing reduced agrochemical applications may contribute to reduced soil degradation. In this sense, several biofertilizers based on nitrogen-fixing microorganisms have shown positive effects on certain cultivated plants, such as maize 3,25,32, sorghum 19, soybeans 10, and rice 12.

Among nitrogen-fixing bacteria, A. brasilense is considered one of the most important plant growth-promoting bacteria 8. On one hand, this bacterium promotes growth and increases plant production, after promoting phytohormone synthesis 5) and biological nitrogen fixation. On the other hand, A. brasilense restricts certain plant pathogens through antibiosis and siderophores 14. In addition, Azospirillum may associate with more than 100 plant species, 14 of which are grasses 30. As stated by Gavilanes et al. (2020), A. brasilense (Ab-V5 and Ab-V6) has been widely used as a commercial inoculant in Brazil 14, with positive effects on grain dry matter and nitrogen accumulation in plants, especially in grain crops such as maize and wheat 13,24.

Given the mentioned phytohormone-producing capacity of this bacterium, inoculation effects could be related to the role played by salicylic acid. Several studies performed with rhizosphere bacteria show that most strains produced metabolites of the AIA type, siderophores and salicylic acid 22. Salicylic acid (SA) is a phenolic secondary metabolite 20 present in plant tissues 33,41, regulating plant growth and increasing crop yield when supplied in low exogenous concentrations 34. In maize, the application of SA increases grain production per plant, total dry biomass, and N, P, K contents 41.

Some hypotheses about the effect of SA and A. brasilense consider the role of SA as a plant hormone and the ability of A. brasilense to fix atmospheric nitrogen and increase nutrient uptake by promoting increased stem growth and grain production 15. The effect of both bioactive products (SA and A. brasilense), effective biomolecules and plant growth regulators 26, depended on the genotype and environmental conditions. In this sense, given the agronomic implications on possible biological fertilization strategies in maize, comparing the effect of both products turns interesting. Thus, this research aimed to study the physiological effect of A. brasilense and SA on growth and grain production of maize plants under field conditions.

Materials and methods

Location

The research was conducted from June 2016 to January 2017 in the locality of Calzada Larga, municipality of Villaflores, Chiapas, México, at 16°21’08.5” N and 93°18’58.2” W and 713 m a. s. l. 8. The predominant climates are warm and semi-warm, with an average temperature of 24.5 ℃, an average rainfall of 1200 mm per year, and the following predominant soil types: lithosols, luvisols, cambisols and vertisols.

Growth conditions and plant material

Seeds of the CLTHW11002 hybrid, yellow maize from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), were manually sowed at 0.8 m between rows and 0.35 m between plants on a luvisol soil with loamy texture and enough water content.

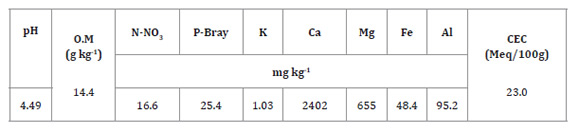

According to the Mexican Official Standard 27, the soil is strongly acidic, free of carbonates and salts, low in potassium, moderately low in organic matter, medium phosphorus (P-Bray) and nitrogen (N-NO3), moderately high in magnesium (Mg) and very high in iron (Fe). Both aluminium content and proportion vs. total soil cations (4.61%) were low, despite the extreme soil acidity (Table 1).

Table 1: Soil chemical properties. Tabla 1: Caracterización química del suelo del área experimental.

O. M: organic matter, CEC: cation exchange capacity.

M. O: Materia Orgánica, CEC: Capacidad de intercambio catiónico.

Two nitrogen fertilizations were applied at 15 days and 30 days after sowing, both at a rate of 75 kg ha-1 of N, for a total dose of 150 kg ha-1 (46-00-00). Weed chemical control was carried out with Velquat 1.5 L ha-1 at 15 days after sowing, and 1.5 L ha-1 Tacsaquat at 60 days after sowing. The fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) was controlled with Cipermetrine 21.12% EC at a dose of 1.0 L ha-1.

Experimental design and treatments

The randomized block experimental design with three treatments and three replicates consisted of T1: salicylic acid (SA), T2: A. brasilense (5 x 108 CFU), T3: control treatment without SA and not inoculated. Each experimental unit measured 25 m2 (5 x 5 m), leaving one border plant on each side of the plot.

Seed inoculation with A. brasilense

The commercial product tested was Azofer®, composed of A. brasilense (50%), peat (37.5%) and calcium carbonate (12.5%). Calcium carbonate allows achieving the ideal pH (6.8-7.0) for the inoculant 6, while not affecting plant growth or development. The concentration of A. brasilense was 5 x 108 CFU’s per gram of commercial product.

For seed inoculation, an inert solution was prepared with 60 g of carbosil-methyl-cellulose adhesive powder dissolved in 1.5 L of distilled water and left to stand for two hours. Subsequently, mointened seeds with the adherent powder were homogeneously covered with the biofertilizer and left to dry in the shade, at room temperature, before sowing.

Imbibition of seeds with salicylic acid

A solution with distilled water and salicylic acid at a concentration of 0.01 mM, was prepared according to Hayat and Ahmad (2007), Gordillo-Curiel et al. (2020) and Rodríguez-Larramendi et al. (2017). The seeds were soaked for 2 hours and left to dry at room temperature before sowing.

Analytical evaluations

For growth measurements at 30 and 60 days after sowing, five plants per replicate were selected, number of leaves per plant (LP) was counted, and plant leaf area was determined in cm2 (LA) with a CI-202 (Bioscience ®) portable leaf area meter. Plant height (PH) was measured with a millimetre ruler. Leaves, stem, roots of the five selected plants were separated, and oven dried at 80°C for 72 hours. Finally, leaves dry weight (LDW), shoot dry weight (SDW) and root dry weight (RDW) were obtained using a Sartorius® analytical balance. Plant dry weight was calculated.

Growth rates

Based on leaf area and dry weight, the leaf area index (LAI) was calculated by dividing plant leaf area (LA) by soil coverage. Root weight fraction (RWF, g g-1) was calculated as the root dry weight vs. plant dry weight ratio. This indicator expresses the “root’s investment” or biomass gain 4. Leaf weight fraction (LWF, g g-1) was calculated as leaf dry weight vs. plant dry weight, estimating leaf partitioning 42. The root mass/leaf mass ratio (dimensionless) estimated phenotypic plasticity in biomass allocation 4. Specific leaf area (SLA, cm2 g-1) was calculated as leaf area/leaf dry weight, reflecting functional traits of leaf morphology such as thickness and density 31 and vegetative vigor 23. Leaf area ratio (LAR, cm2 g-1), one important determinant of plant relative growth rate 42, was calculated as leaf area by plant dry weight.

Yield components

When the crop reached physiological maturity, five plants per treatment were selected in each replicate and ear length (EL, cm), ear diameter (ED, cm), 100-grain dry weight, and dry grain yield per plant (Yield, g plant-1) at 14% grain moisture, were assessed.

Statistical analysis

ANOVA with a randomized block design followed by LSD mean comparison test was conducted considering p ≤ 0.05. ANOVA assumptions were verified by the Cochran and Barttlet tests. A multivariate Principal Component Analysis (PCA) searched for a possible relationship between plant growth, yield, ear weight and ear size. All analyses were performed with the statistical package STATISTICA® release 8.0 39.

Results

The number of leaves per plant was significantly higher in inoculated plants, compared to those treated with SA and control, the latter of which produced fewer leaves. Despite a tendency towards more leaves per plant on both sampling dates (at 30 and 60 das), at 60 das, this difference was not significant (Table 2, page 21).

Table 2: Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and A. brasilense on growth of maize plants at 30 and 60 days after sowing (das). Tabla 2: Efecto del ácido salicílico (AS) y A. brasilense en el crecimiento de plantas de maíz a los 30 y 60 días después de la siembra (dds).

ns: Not significant; * Statistically significant for p ≤ 0.05, das: days after sowing.

Ns: sin diferencias significativas, * Diferencias estadísticas significativas para p ≤ 0,05, dds: días después de la siembra.

However, plant height and stem diameter were significantly higher in plants grown from SA-treated seed, and even higher than those inoculated with A. brasilense at 30 das. At 60 das, no significant difference in plant height was observed between SA and A. brasilense-treated plants (Table 2).

Leaf area was larger in SA-treated plants at 30 das than control plants. The latter exhibited no significant differences concerning those inoculated with A. brasilense. At 60 das, no difference in leaf area was observed among treatments (Table 2).

Leaf dry weight was statistically higher in plants treated with SA and A. brasilense than in control plants at 30 das. At 60 das this difference was even higher for SA-treated plants followed by A. brasilense, compared to the control. Similar results were observed for root and stem dry weight and, therefore, for total plant dry weight. However, stem dry weight was statistically different at 60 das (Table 2).

Table 3 (page 22) shows the effect of bioactive products on growth ratios, only significant at 30 das, when an increasing leaf area index was observed for the SA treatment.

Table 3: Effect of the application of salicylic acid (SA) and A. brasilense on growth rates of maize plants at 30 and 60 days after sowing (das). Tabla 3: Efecto de la aplicación de ácido salicílico (AS) y A. brasilense en los índices de crecimiento de plantas de maíz a los 30 y 60 días despues de la siembra (dds).

Ns: Not significant; * Statistically significant for p ≤ 0.05.

Ns: sin diferencias significativas, * Diferencias estadísticas significativas para p ≤ 0,05 dds: días después de la siembra.

No difference was observed between A. brasilense and control. At 60 das, such growth-stimulating effects were not significant (Table 3, page 22).

The higher leaf growth values observed with SA and A. brasilense at early stages of maize plant development (Table 2) was similar to the increase detected in ear length and weight, and yield per plant (Figure 1, page 22).

Box and vertical lines indicate the standard error and standard deviation, respectively.

Los cuadros y las líneas verticales indican el error etándar y la desviación estándar de la media respectivamente.

Figure 1: Effect of salicylic acid and A. brasilense on A) ear length and diameter, B) yield and 100-grain weight and C) ear weight. Figura 1: Efecto del tratamento con ácido salicílico y A. brasilense en: A) longitud y diámetro de la mazorca, B) rendimiento y peso de 100 granos y C) peso de la mazorca.

Plants treated with SA and A. brasilense developed longer ears, consistently with the higher 100-grain weight (Figure 1 B, page 22), ear weight and yield per plant (Figure 1 B, C, page 22).

Considering vegetative growth, ear size and grain production, a PCA allowed establishing the effects of both bioactive products as a function of the evaluated variables (Figure 2).

Figure 2: PCA biplot of growth variables, ear dimensions and grain yield of corn plants treated with SA and A. brasilense, according to components C1 (48.) % and C2 (16.20%). Figura 2: Biplot de las variables de crecimiento, dimensiones de la mazorca y producción de granos de plantas de maíz tratadas con AS y A. brasilense, en el plano formado por las componetes C1 (48.) % y C2 (16.20%).

Component 1 (48.58%) discriminates control plants from both bioactive treatments, and component 2 (16.20%) discriminates both bioactive treatments. Variables related to biomass accumulation and stem diameter, discriminate in favour of SA treatment, while variables related to leaf growth, plant height, ear dimensions and grain yield, separate the A. brasilense treatment (Figure 2).

Discussion

Maize growth response to seed inoculation with A. brasilense and imbibition with SA on two sampling dates suggests a possible relationship with plant physiological stage and ontogeny, something to be further addressed in future research. The effect of both bioactive products resulted organ dependent.

The results further demonstrate that SA and A. brasilense have similar effects, promoting vegetative growth of maize plants at the early stages. However, these effects depend on sampling date 34 and particularly, on plant organ. This effect is probably given by SA and A. brasilense sharing an analogous property, stimulating hormone synthesis and interacting with cytokinins. SA constitutes a plant hormone exceeding plant immunity and abiotic stress 34. In coordination with cytokinins, ethylene, auxins, gibberellins, jasmonic acid and abscisic acid, SA significantly contributes to growth and development regulation, although through unknown mechanisms 34. In this sense, it has been shown that the growth-promoting effects of SA could be related to hormone modulation 1,37 or gas exchange improvement 39.

The PCA showed correlations between leaf growth vs. plant height, and ear size vs. increased grain production. These aspects are related to the A. brasilense enhanced nitrogen absorption, even in fertile soils 15, and enhanced hormone synthesis, including auxin, gibberellin, and cytokinin 2,17.

The effect of SA on grain production in maize plants is also supported by other studies. Low doses of SA induce increased ear length and maize grain yield 41. However, in our research, SA was applied to leaves 41 and not seeds, opening a new field of research.

Positive plant responses to inoculation with A. brasilense might be given by biological nitrogen fixation, probably overshadowed by the nitrogen fertilization carried out in the experiment, and by plant hormonal production. In this regard, inoculations with A. brasilense had improved root growth and development of Setaria viridis grass after increased CO2 fixation and reduced accumulation of photo-assimilated carbon in leaves, resulting in greater canopy growth, increased water content in plant tissues, and reduced stress 24,28. In addition, increased production of indoleacetic acid may improve nutrient uptake by augmenting root growth 24,28. Zeffa et al. (2019) studied A. brasilense inoculated seeds, finding intensified plant growth, improved biochemical traits and raised NUE under nitrogen deficit. Other authors have found that regardless of nitrogen source and dosage, A. brasilense increased maize grain yield 16.

SA effects on plant dry weight are probably related to SA ability to increase N, P2O5 and K2O contents in plant tissues 41. On the other hand, seed inoculation with A. brasilense stimulates root growth, increases root exploration capacity and promotes biological nitrogen fixation, which may be related to higher grain production and ear length in inoculated plants. Specifically, in maize, other studies have shown that inoculations with nitrogen-fixing bacteria result in a 9% increase in maize grain production 16.

Our results show that SA and A. brasilense had similar stimulating effects on growth and yield of maize plants, from early stages of plant ontogeny. This physiological effect may be related to the ability to interact with other hormones 37 or promote hormone synthesis 16. However, we suggest caution before issuing a hypothesis on this matter as, apart from the above-mentioned properties, A. brasilense contributes to plant nutrition through biological nitrogen fixation, a fact that may mask the effects of both bioactive products on plant growth and development.

Conclusions

We consider that the results obtained show robust evidence supporting theoretical and methodological bases, as well as sufficient evidence on the physiological effect of S.A and the bacterium A. brasilense on growth and grain production of maize under field conditions. Such results are relevant to the design of biological fertilization strategies with the respective reduction of pollutants. Considering economic and environmental sustainability, both products can be considered within the agronomic practices of maize cultivation.

The results indicated that SA and A. brasilense exhibited similar stimulating effects on growth and yield of maize plants, from early stages. SA induced greater plant biomass accumulation, with a tendency to maximize root dry mass, while A. brasilense stimulated greater leaf growth and plant height, consequently inducing increased ear growth and grain production.