Introduction

Organic agriculture (OA) produces chemical-free food for human consumption and under safer environmental conditions than conventional agriculture. OA considers minimum external inputs while avoiding synthetic fertilizers and pesticides 1,17,22,30,31. Globally, approximately 2.7 million producers distributed mainly in India, Uganda, and Mexico 7, cultivate under OA. The North American continent represents 16% of worldwide OA, with 11.2 million hectares (ha) of organic production 7. OA in Mexico began in the 1980s. During 2018, the Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP) (Fisheries Agrifood Information Service) reported 1,126,000 ha organically managed, 162,386 ha planted and certified as organic, and 11,380 ha of orchards in transition from conventional to organic 6,24. In 2019, Mexico ranked sixth globally for Valencia orange [ Citrus x sinensis (L.) Osbeck (pro. sp.)] production, contributing 6.3% of global volume 10,25.

Due to global demand for citrus, Mexico is investing in citriculture, primarily in Veracruz and Michoacan states. In Veracruz, different citrus industries have invested in organic Valencia orange production 12. Within the OA scope, organizations establish requirements and standards. At the beginning of 2001, the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) developed an integrated organic management strategy to control and regulate the vector of Citrus Huanglongbing disease, Diaphorina citri Kuayama in Mexico 3,21. This infection, previously called Citrus Greening Disease is caused by unculturable phloem-limited bacteria. In February 2006, the Organic Products Law was issued in Mexico, then followed by specific regulations in 2010. In 2013, an agreement was signed on guidelines for the organic operation of agricultural activities 26. The National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural and Livestock Research (INIFAP), together with the Consejo de Productores y exportadores de limon Persa (COPELP) (Council of Producers and Exporters of Persian Lemon A.C.) in 2017, compiled a list of bioinsecticides against D. citri allowed within organic citriculture 8.

Conceptual framework addressing OA

Agricultural sustainability is defined/limited by the effects of conventional or intensive agriculture. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1991) conceptualizes sustainable agriculture as:

“The management and conservation of natural resources and the orientation of technological and institutional changes in order to ensure the continuous satisfaction of human needs for present and future generations. Such sustainable development conserves soil, water, and animal and plant genetic resources; does not degrade the environment; and is technically appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable.”

Thus, sustainability is an interaction between society and nature over time, including social progress towards agroecosystem sustainability 4.

In a three-dimensional approach considering broad agroecology, Toledo (2012) emphasized the relationship between scientific research, new practices, and social movements in Latin America (including the Caribbean), describing the five regional kernels of agroecology: Brazil, the Andean Region, Central America, Mexico, and Cuba. He found a tripartite and interrelated innovation process (knowledge, technology, and sociopolitics) interacting with recent political and cultural events ( e.g. the emergence of governments with social perspective, and indigenous and peasant resistance). Contemporary agroecology encompasses the relationship between scientific paradigms and technological changes with social and political movements, providing important transformational gains toward building sustainable societies 27. Agroecology enhances perspectives for researchers, growers, and industries seeking more environmentally friendly production practices to protect soil, flora, fauna, and ecosystems.

Among management methods for improving agroecosystems, OA (which focuses on agroecology) uses efficient technologies combined with ecological knowledge to reduce negative environmental impact 30. Niggli (2015) states that OA is a practical way of developing sustainable agriculture.

There are four fundamental pillars in agroecology 28. The first pillar is “to build biodiverse agroecosystems such that the composition (species richness, with high genetic variability) and structure (abundance and spatial/temporal distribution of species) acquire complexity, achieving the objectives sought by farmers to maintain ecosystem functionality…” The second pillar consists of “capturing as much solar energy as possible through photosynthesis. This energy supports a complex food chain and agroecosystemic productivity”. The third pillar refers to “promoting the greatest recycling of materials introduced into the production process, the incorporation of organic fertilizers compensating for harvest output, the least physical soil intervention, and the use of green manures and ground cover for erosion prevention...” The fourth pillar states the “efficient use of water, a scarce resource”. These pillars help build resilient, sustainable, and socially accepted agroecosystems for communities internationally.

According to IFOAM basic standards 13, “Organic Agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems, and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic Agriculture combines tradition, innovation, and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and good quality of life for all involved.”

In Mexico, the Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development defined OA as an activity prescinding from agrochemicals and developed using natural inputs (no artificial fertilizers or pesticides) aiming to obtain vegetables and animal products or subproducts free of toxic residues 23. According to Niggli (2015), the objective is to support farm ecological and social quality, increasing food production. OA development can be characterized by comprehensive social, ecological, and technological innovations, where dynamic interactions among farmers and scientists are included. According to Kodirekkala (2017), social internal factors interact with external factors, affecting traditional ecological knowledge. Internal factors include socioeconomic and environmental conditions determining decision-making processes, which together with external factors, such as local economy and society, are affected by markets and regulations.

Our research studied the transition degree of Valencia orange orchards towards OA in northern Veracruz State. To this end, the approach described by Niggli (2015) was complemented by the internal and external factors proposed by Kodirekkala (2017). Our research also followed the principles and practices of OA promoted by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture 13,22, considering production vs. environment 16. This included the law and regulations of organic products 15,20 and the Guidelines for the Organic Operation of agricultural activities 11, describing all regulations for OA transition in Mexico.

The hypothesis stated that Valencia orange producers in northern Veracruz State are transitioning towards organic production, resulting from the dynamic temporal interactions between farmers and institutions strengthening this producing model. Therefore, the objective was to determine the degree of transition towards organic production and management of Valencia orange in the municipalities of northern Veracruz State.

Materials and methods

Sample collecting

Our investigation was performed in northern Veracruz State, in the municipalities of Álamo Temapache, Tantoyuca, Chalma, Chicontepec, and Ixhuatlán de Madero, where Valencia orange producers are transitioning from conventional to organic management. To determine management transition, structured interviews were conducted on 106 organic producers of Valencia orange [( Citrus x sinensis (L.) Osbeck (pro. sp.)]. These producers were grouped into four established civil associations ( Table 1).

Table 1: Number of interviewed producers per Association and Municipality in northern Veracruz State. Tabla 1: Número de productores entrevistados en cada asociación de cítricos orgánicos de municipios de la zona norte de Veracruz.

In the absence of an official register of organic Valencia orange producers in northern Veracruz State, we implemented a non-probabilistic sampling protocol using the snowball method 5, carried out in March 2021.

Operationalization, variable weighting, and transition index construction

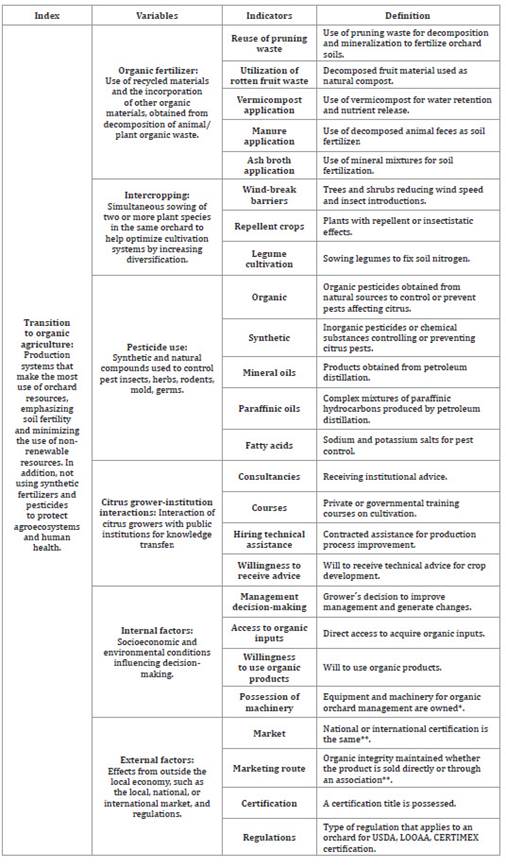

Table 2 (page 31) lists all variables and indicators.

Table 2: Variables and indicators contributing to the Transition Index. Tabla 2: Definición de variables e indicadores que componen el Índice de Transición.

*According to the Guidelines for the Organic Operation of agricultural activities 11, in the process and organic operation towards general conversion, “the machinery has to be different from that of conventional…”. ** The Organic integrity, that is, the quality of an organic product obtained in accordance with the Law, which must be maintained during production and handling until the final point of sale... 20.

* De acuerdo con los Lineamientos para la Operación orgánica de las actividades agropecuarias 11 en la operación orgánica y sus procesos hacia la conversión general, “la herramienta y maquinaria utilizada en la operación orgánica deberá diferenciarse de la utilizada en la actividad agropecuaria convencional…”. **La integridad orgánica es la cualidad de un producto orgánico obtenido de acuerdo con la Ley, la cual deberá ser mantenida durante la producción y manejo hasta el punto final de venta… 20.

Based on the theoretical framework, the variables and indicators were defined and operationalized. The questionnaire comprised dichotomous answers. Variable and indicator weighting was carried out according to the professional experience of the researchers 29. Relative weights were normalized by multiplying each indicator in the questionnaire with the corresponding weighted value. Then their sum was multiplied by the weighted value of each variable 29. The sum of the normalized relative weights for all the indicators must equal 1 ( Table 3, page 32).

Table 3: Operationalization and weighting of variables and indicators for determining the Transition Index. Tabla 3: Operacionalización y ponderación de variables e indicadores para determinar el Índice de Transformación.

Therefore, the transition index is the sum of the results of the weighted variables and indicators. Coded and tabulated data in an Excel® spreadsheet allowed variables and index calculation. Then, correlation analyses were carried out with all the variables dedicated to OA practice using Statistica software 9. Statistically different variables were classified into lower, intermediate, and upper by Line Plot. An ANOVA compared these values with the transition index. Although surveys started in different years with OA as an empirical division, they were divided into incipient, intermediate, advanced, and organic, from 1 to 6 years, 7 to 12 years, 13 to 18 years, and 19 to 26 years, respectively. The years dedicated to OA were plotted against the transition index.

Results and Discussion

Table 4 shows minimum and maximum values for each indicator, meaning some growers are implementing more organic management than others.

Table 4: Maximum, minimum, and mean values of variables A to F, and the transition index. Tabla 4: Valores máximos, mínimos y media de las variables e índice de transformación. Cada una de las letras identifica las distintas variables.

A: organic fertilizer. B: intercropping. C: pesticide use. D: interaction between citrus growers and institutions, E: internal factors, F: external factors.

A: fertilizante orgánico. B: intercalado de cultivo. C: uso de pesticidas. D: interacción citricultores-instituciones, E: factores internos. F: factores externos.

The average transition index was 0.768, indicating an average value of transition towards OA, consistent with the number of years dedicated to OA.

Figure 1 (page 34) shows biplots and consequent correlations between variables.

A: organic fertilizer. B: intercropping. C: pesticide use. D: citrus grower institution interaction. E: internal factors. F: external factors.

A: fertilizante orgánico. B: intercalado de cultivo. C: uso de pesticidas. D: interacción citricultores-instituciones. E: factores internos. F: factores externos.

Figure 1: Correlation matrix. Figura 1: Matriz de correlación.

Significant positive correlations existed between the citrus grower/institution interaction and intercropping (p = 0.0281; r = 0.2133), and the citrus grower/institution interaction with internal factors (p = 0.0257; r = 0.2167). A weak and negative correlation between pesticide use and citrus grower/institution interaction (p = 0.0369; r = -0.2030) was given by producers buying pesticides from agrochemical suppliers (based on seller recommendations) without seeking advice from institutions. Thus, the citrus grower/ institution interaction with intercropping constitutes a factor providing recent information in Veracruz State. Production of organic C. sinensis is gaining importance given a favourable international market demand and different processing industries generating products such as orange juice, essential oils, and cosmetics. The International Copper Chemistry (IQC), Cítricos ex S.A. of C.V. (Citrex), Citrusper, and Procitris, S.A de C.V. industries are sought by countries such as the United States, Canada, the European Union, and Asia 12. According to Bigaran and Ramos (2022), it is also important to measure the logistical performance of distribution channels of different lengths (km) based on criteria supported by the concept of food miles and in the main logistical practices of distribution of fruits and vegetables, contribute to the definition of strategies to mitigate food losses.

Figure 2 (page 34) shows the categorized transition index with the statistically different factors according to Line plot.

Figure 2: Analysis of the transition index and variables with statistical differences, heuristically divided by Line plot. Figura 2: Análisis del índice de transición con las variables divididas heurísticamente por Line plot que presentaron diferencia estadística.

Growers with higher transition indices use intercropping and have more interaction with institutions, while increased activities help growers obtain certification for organic production. Yet, given all growers applied organic fertilizers and organic pesticides, other variables were not different within the categorized transition index. Plant nutrition with organic fertilizers such as pruning residues, animal feces and mixtures of mineral products promotes vigorous and healthy crops. Additionally, only organic pesticides, and sodium/potassium salts are used to control or prevent pests affecting citrus. In this sense, organic citriculture results complex. Changes in scientific-technological paradigms are built in constant association with social movements, where sustainable citriculture is in constant transition and growers must interact with all agents related to this industry. Thus, organic citriculture is an alternative for researchers, producers and industrialists seeking less environmental impact and human well-being 27. Improving organic practices requires social, ecological, and technological innovation in dynamic interaction among farmers and scientists strengthening system resilience and exploiting research from diverse scientific disciplines 18.

The citrus grower/institution interaction evidences how OA is achieved through a dynamic interaction among farmers and scientists promoting a comprehensive culture including social, ecological, technological, and environmental innovation 18. This is achieved because producers are willing to receive advice, control, and supervision in different cultivation activities, while also getting involved in training activities.

Figure 3, shows a highly significant difference (p= 0.0000) between the transition index and the degree of transition to OA, indicating that as conversion time increased, more practices approved by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (2005) were implemented.

Figure 3: Relationship between the transition index and years of conversion to organic agriculture. Figura 3: Relación entre el índice de transformación y los años de conversión hacia la agricultura orgánica.

Importantly, several growers with less time under OA could apply all practices as advanced or organic according to the weighting of variables and indicators, and all had their orchards certified as organic. Current challenges should satisfy the production demand for Valencia orange while reducing waste, improving the production of healthy oranges for consumption, conserving natural resources, mitigating and adapting to climate change and reducing social and cultural injustice and cultural erosion ( i.e. the loss of traditional knowledge). Improvement of most agricultural activities is strongly needed 14.

Conclusions

Even considering all interviewed producers had orchards certified as organic, Valencia orange producers in northern Veracruz State are still transitioning to organic production above an average transition index (0.7687). Producers with more years in organic production showed a higher transition index. This transition degree is primarily influenced by the organic matter recycling practices employed, the non-use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, and the dynamic interactions between producers and institutions. Yet, internal and external factors did not significantly influence the process of transition towards an organic model for citrus production.