Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista argentina de cirugía

On-line version ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.112 no.4 Cap. Fed. Dec. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v112.n4.anwex

Articles

Anal fissure - anatomy, pathogenesis and treatment

1 Department of Colorectal Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston, FL. USA

Introduction

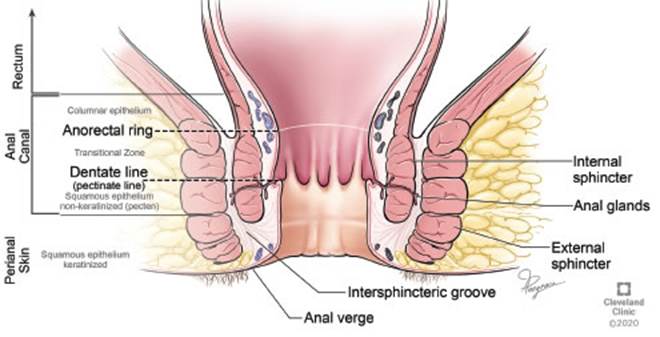

Anal fissure, also known as fissure-in-ano, is a common anal pathology characterized by a linear tear of the anal mucosa, distal to the dentate line (Figure 1). This painful condition can be classified as acute, with symptoms lasting less than 6 weeks, or chronic when the symptoms last longer than 6-8 weeks. The chronicity of the fissure may also be differentiated by gross appearance where acute fissures show a simple tear in the anoderm as compared to chronic anal fissures where muscle fibers of the internal anal sphincter can be seen. This is also often accompanied with a sentinel skin tag and hypertrophied anal papillae. The majority of fissures are located at the midline, where 90% are posterior and 10% are located anteriorly. An atypical location of a fissure may indicate the presence of an underlying disease such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), primarily Crohn’s disease, as well as tuberculosis, syphilis, herpes, gonorrhea, leukemia or HIV.

Anatomy

Anal canal

The anal canal, the terminal part of the large intestine, is a complex anatomical structure which accommodated to its vital role in continence. The “anatomical” or “embryological” anal canal, which is 2 cm long, extends from the anal verge to the dentate line. The “surgical” or “functional” anal canal is longer, roughly 4 cm, and extends from the anal verge to the anorectal ring (Figure 2). This muscular ring, although lacking embryological significance, is of great importance since damage to this structure during anorectal surgery can lead to fecal incontinence.

Figure 2 Anal canal anatomy. *Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography ©2020. All Rights Reserved.

The anal canal is lined with four different types of epithelium (Figure 2). The most proximal lining of the anal canal is a single layer of cuboidal columnar cells, similar to rectal mucosa. This layer extends to about 1 cm proximal to the dentate line, where the anal transition zone begins. The anal transition zone consists of several layers of cuboidal cells and has a deep purple color due to the underlying internal hemorrhoidal plexus. Below the dentate line, the cutaneous part of the anal canal arises and consists of modified squamous epithelium, which lacks hair or glands. The anal verge marks the lowermost edge of the anal canal, distal to the anal verge the lining becomes thicker, pigmented and contains features of normal skin such as hair follicles and apocrine glands.

Anal sphincter

The muscles of the anorectal area comprised of two muscle groups: the sphincter and the lateral compressor muscles. In this review we will focus on the sphincter muscles, which knowledge of their anatomy is essential for surgeons treating anal fissures.

Internal anal sphincter (IAS)

The IAS is a 2 to 3 mm thick, 2.5 to 4 cm long, circular muscle composed of the distal long condensation of the inner circular muscle layer of the rectum. On physical examination the lower edges of the IAS about 1 cm distal to the dentate line.

External anal sphincter (EAS)

The EAS is a cylinder of striated muscle that envelopes the entire length of the inner tube of smooth muscles. The uppermost end of the external muscle fuses with the puborectalis part of the levator ani muscle. The EAS ends slightly distal to the IAS.

Conjoined longitudinal muscle

This muscle is composed of fanlike fibers that run through the internal anal sphincter, intersphinteric grove and also through the external anal sphincter. These fibers ultimately insert into the perianal skin. It is the distribution of this longitudinal fibers that make this complex of smooth and striated muscles a functionally solid unit, which is imperative in the defecation mechanism.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of anal fissures is still debated. While many studies have shown that patients with anal fissures have an increased pressure within the anal canal, though it is unclear which preceded beforehand, the presence of the fissure or the increased anal pressure. Some authors also hypothesized that anal fissures are a sequalae of an infectious process. In their historical paper in 1960, Dubra and Petrozzi et al. state that “Anal fissure and fistula have the same etiopathogenesis: infection of the anal glands”1. However, to date, most authors believe that trauma to the anoderm, whether from passage of hard or large stool, irritation from frequent stools or diarrhea, anorectal surgery or anal instrumentation are the preceding causes2. The anodermal tear exposes the IAS, theses exposed sphincter fibers and nerve endings cause IAS spasms, pain and subsequently increase the anal canal pressure. The hypertonicity of the sphincter further exacerbates the problem with preventing healing by causing tissue hypoxemia due to diminished blood flow. Hypertonic sphincter has been associated with anal fissures3 and so as diminished blood flow to the anoderm4. This relation between sphincter hypertonicity and diminished blood flow is the basis for modern fissure treatment.

Treatment

Medical treatment

Non-operative treatment is aimed to pharmacologically reduce the anal sphincter tone and promote blood flow to the anoderm. Medical treatment may relieve symptoms in many patients with an acute fissure and is worthwhile trying in many patients with chronic fissures.

Topical nitrites

Topical nitrates work by relaxing the internal anal sphincter through the release of nitric oxide. The use of nitrates for the treatment of anal fissures was introduced in a preliminary investigation by Gorfine in 19955. Nitric oxide causes smooth muscle relaxation by increasing cGMP levels via guanylyl cyclase. Exogenous nitric oxide donors, such as glyceryltrinitrate (GTN), cause reduction in sphincter spasm and show potential in healing chronic anal fissures. In a Cochrane review of including 18 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of nonsurgical therapies for anal fissures, GTN was found to be marginally but significantly better than placebo in healing anal fissure (48.9% vs. 35.5%, p < 0.0009), but late recurrence of fissure was common, in the range of 50% of those initially cured6. One major side effect of the of nitrates use is severe headaches, that are disabling in over 20% of patients. It can be occasionally resolved by decreasing the amount of applied ointment, however it may require treatment termination.

Calcium channel blockers

Topical calcium channel blockers have been used as alternatives to GTN in the treatment of anal fissures. Their mechanism of action is facilitated by blocking L-type calcium channels in the internal anal sphincter muscle fibers, which cause muscle relaxation and decreased anal tone. Although oral formulations may be used, they can have adverse systemic side effects such as hypotension or orthostasis. For this reason, Nifedipine or Diltiazem are usually compounded into topical gel and are applied topically. A randomized study comparing Nifedipine to Glyceryl Nitrate in treatment of chronic anal fissure, concluded the Nifedipine was more effective at healing chronic anal fissure and had fewer side effects, however recurrences were frequent with both drugs7. The main side effect reported is itching, which is rare and rarely causes termination of treatment.

Botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin (BT) is used to temporary paralyze the internal anal sphincter and subsequently improve blood flow to the anoderm. The toxin is produced by the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium Botulinum and works on the presynaptic nerve terminals at the neuromuscular junction and prevents the release of acetylcholine in synapses. The use of botulinum toxin as an effective treatment for anal fissures was first described by Jost8, with and the toxin injection reducing the anal resting pressure by 30%. The procedure is usually preformed as an outpatient procedure, under monitored anesthesia care (MAC) and its effect lasts for up to 3 months. In a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs, including 393 patients, 194 treated with BT and 199 with GTN, Sahebally et al. concluded that there was no statistically significant difference in fissure healing or recurrence between BT and GTN. BT was associated with a higher rate of transient anal incontinence (OR = 2.53, 95% CI 0.98-6.57, P = 0.06) but significantly fewer total side effects (OR = 0.12, 95% CI 0.02-0.63, P = 0.01) and headache (OR = 0.10, 95% CI 0.02-0.60, P = 0.01) compared with GTN9. There is a considerable variation among clinicians in the injection site and also in the amount of toxin used. Option for injection sites include into the internal sphincter, into the intersphinteric grove, into the fissure directly or on either side of the fissure. The amount of toxin used is typically 20 units, but some researches have shown higher success rates after injecting 40 units, with no increase in complications10. In a meta-analysis aimed to evaluate dose dependent efficacy, a total number of BT units per session ranged from 5 to 150 IU. The authors did not observe a dose-dependent efficiency, postoperative incontinence rate was not related to the BT dosage and also no difference in healing rate was observed in regard to the site and number of injections per session11.

Operative treatment

In more chronic conditions, or in fissures recalcitrant to medical treatment, surgical procedures may be the only treatment of anal fissures. In the past, posterior sphincterotomy was recommended, but this approach resulted in a “keyhole” deformity. Eisenhammer described a lateral internal sphincterotomy and this approach has been widely accepted11. With a very high healing rate, some reports as high as 95% in some reports, internal sphincterotomy has become the gold standard for the treatment of anal fissures, which all other treatment options are compared to.

Open lateral internal sphincterotomy

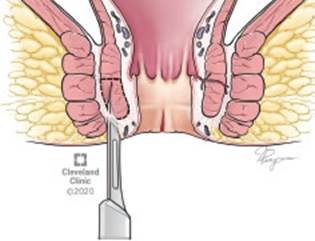

This procedure is preformed while the patient is in either the lithotomy or prone jack knife positions. The authors prefer the latter as this allows better exposure. General or MAC anesthesia is administered and is supplemented by a local block with bupivacaine and epinephrine. The local block allows relaxation of the sphincter and facilitates surgery. An anal retractor is used and identification of internal sphincter and the intersphincteric groove is achieved. This is followed by an incision in the perianal skin overlying the intersphinteric groove. A fine instrument is then used and inserted into the intersphinteric plane and the internal sphincter is isolated up to the dentate line (Figure 3). The internal sphincter is then divided either with fine scissors or electrocautery. Classically, the muscle is divided up to the dentate line, but modified sphincterotomy is preformed by dividing the sphincter up to the level of the proximal extent of the fissure. The perianal incision is then closed with an absorbable suture.

Figure 3 Open Lateral sphincterotomy - exposure of muscle fibers. *Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography ©2020. All Rights Reserved.

Complications from internal sphincterotomy are rare and include pain, bleeding, urinary retention, abscess, and fistula formation and delayed wound healing. A much more worrisome complication is incontinence. The overall incidence of incontinence in a recent meta-analysis was reported at 3.4 to 4.4%12. Surgical therapy, however, was associated with shorter time to symptomatic relief, higher rates of healing, lower rates of recurrence and with a success rate of over 95%.

Closed lateral internal sphincterotomy

With this technique, a narrow blade scalpel is inserted into the intersphinteric groove and advanced until the tip of the blade is up at the same level as the apex of the fissure (Figure 4). The tip is then turned to face the IAS, and muscle division is preformed during scalpel withdrawal. Several superficial passes may be needed to accomplish the needed muscle fiber transection. Due to the small size of the defect in the anoderm, suture closure is not needed. Complications rate are low and are comparable to those encountered with the open technique.

Advancement flap

Fissurectomy with a dermal advancement flap, is indicated in some instances where a fissure exists without a hypertonic sphincter or a sphincterotomy is contraindicated. This procedure entails excision of the fissure, converting a chronic fissure to an acute fissure while maintaining the integrity of the IAS. This is then followed by the transfer of well-vascularized skin flap into the anal canal to cover the anal fissure base and sutured in place. A meta-analysis comparing lateral internal sphincterotomy to advancement flap, with 150 patients in each group, showed higher rate of unhealed fissures associated with an advancement flap, but the difference failed to reach statistical significance (OR = 2.21, 95% CI = 0.25 to 19.33, p = .47), Advancement flap was also associated with a statistically significantly lower rate of incontinence compared to sphincterotomy (OR = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.36, p = .002)13.

Future treatment

A promising novel approach with the use of regenerative medicine was described by Andjelkov and coworkers. Autologous adipose derived regenerative cells were used to treat chronic anal fissures. The authors reported complete healing of anal fissures in all twelve patients treated after 3 months14. In another pilot study, autologous adipose tissue transplant has shown 75% healing of anal fissures in patients with chronic anal fissures who failed medical or surgical treatment6. While these studies are preliminary and include small number of patients, they explore the potentially promising role of regenerative medicine in treating chronic anal fissures.

Conclusion

Anal fissure is a common and painful condition and is associated with hypertonicity of the anal sphincter. Decreasing the anal pressure is the cornerstone of medical and surgical management. Treatment options have evolved considerably since the historical publication by Dubra et al. and now encompass medical management with agents that pharmacologically reduce the anal sphincter tone. While these agents are used primarily, high recurrence rates and chronic fissures still require surgical intervention. The gold standard of surgical intervention remains the lateral internal sphincterotomy.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Dubra C, Petrozzi CA. Fisura anal. Antomia, patogenia, tratamiento. Rev Argent Cirug. 1960; 1(2):65-70. [ Links ]

2. Beaty J, Shashidharan M. Anal Fissure. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016; 29(01): 30-7. [ Links ]

3. Farouk R, Duthie GS, MacGregor AB, Bartolo DCC. Sustained internal sphincter hypertonia in patients with chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994; 37(5):424-9. [ Links ]

4. Schouten WR, Briel JW, Auwerda JJ, De Graaf EJ. Ischaemic nature of anal fissure. Br J Surg 1996; 83(1):63-5. [ Links ]

5. Gorfine SR. Treatment of benign anal disease with topical nitroglycerin. Dis Colon Rectum 1995; 38(5):453-6; discussion 456-7. [ Links ]

6. Lolli P, Malleo G, Rigotti G. Treatment of chronic anal fissures and associated stenosis by autologous adipose tissue transplant: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum 2010; 53 (4):460-6. [ Links ]

7. Ezri T, Susmallian S. Topical Nifedipine vs. Topical Glyceryl Trinitrate for Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46(6):805-8. [ Links ]

8. Jost WH, Schimrigk K. Use of botulinum toxin in anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum . 1993; 36(10):974. [ Links ]

9. Sahebally SM, Meshkat B, Walsh SR, Beddy D. Botulinum toxin injection vs topical nitrates for chronic anal fissure: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Colorectal Dis. 2018; 20(1):6-15. [ Links ]

10. Fernández López F, Conde Freire R, Ríos Ríos A, García Iglesias J, Caínzos Fernández M, Potel Lesquereux J. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of anal fissure. Dig Surg. 1999; 16(6):515-8. [ Links ]

11. Bobkiewicz A, Francuzik W, Krokowicz L, et al. Botulinum Toxin Injection for Treatment of Chronic Anal Fissure: Is There Any Dose-Dependent Efficiency? A Meta-Analysis. World J Surg 2016; 40(12):3064-72. [ Links ]

12. Nelson RL, Manuel D, Gumienny C, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the treatment of anal fissure. Tech Coloproctol 2017; 21(8):605-25. [ Links ]

13. Patti R, Famà F, Tornambè A, Asaro G, Di Vita G. Fissurectomy combined with anoplasty and injection of botulinum toxin in treatment of anterior chronic anal fissure with hypertonia of internal anal sphincter: a pilot study. Tech Coloproctol. 2010; 14 (1):31-6. [ Links ]

14. Andjelkov K, Sforza M, Barisic G, Soldatovic I, Hiranyakas A, Krivokapic Z. A novel method for treatment of chronic anal fissure: adipose-derived regenerative cells - a pilot study. Color Dis 2017; 19(6):570-5. [ Links ]

text in

text in