Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista argentina de cirugía

versión On-line ISSN 2250-639X

Rev. argent. cir. vol.113 no.1 Cap. Fed. abr. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25132/raac.v113.n1.1501.ei

Articles

Routine laparoscopic management of common bile duct stones

1 Servicio de Cirugía General del Hospital Dr. Cosme Argerich. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Introduction

The incidence of common bile duct stones associated with cholelithiasis increases with age and is about 15-20% in the 8th decade of life, but its management is still controversial1. There are usually two different treatment options: preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy (two-stage procedure), or single-stage treatment with intraoperative resection of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The main differences between the two treatments include length of hospital stay, costs and training in laparoscopic surgery1,2.

The primary outcome of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of single-stage laparoscopic surgery in a consecutive series of patients with cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis over a period of 10 years. The secondary outcome was to analyze the variables than can modify the efficacy and safety of this approach.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective study at the department of General Surgery, Hospital Cosme Argerich, of prospectively collected data retrieved from an ad hoc database of patients with choledocholithiasis diagnosed by routine intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) over a 10-year period (from July 2008 and July 2018). Patients with previous cholecystectomy (residual stones), severe acute cholangitis, high perioperative risk and severe acute pancreatitis were excluded.

Preoperative variables

▪▪Age

▪▪Sex

▪▪Diagnosis on admission: symptomatic cholelithiasis, acute cholecystitis, acute biliary pancreatitis and choledocholithiasis.

Intraoperative variables

▪▪Operative time

▪▪Rate of successful transcystic exploration and successful choledochotomy

▪▪Conversion rate

▪▪Rate of favorable versus unfavorable cystic duct anatomy

▪▪Relation between cystic duct diameter and gallstone size

▪▪Prevalence of common bile duct stones

▪▪Number, size, and site of gallstones

Postoperative variables

▪▪Complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification3

▪▪Length of hospital stay

▪▪Residual stones

▪▪Biliary fistulas

▪▪Reoperations

Definitions

▪▪Choledocholithiasis: common bile duct diameter > 8 mm or visualization of the gallstone by ultrasound, total bilirubin values > 2 mg/dL or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) > 200 IU/L.

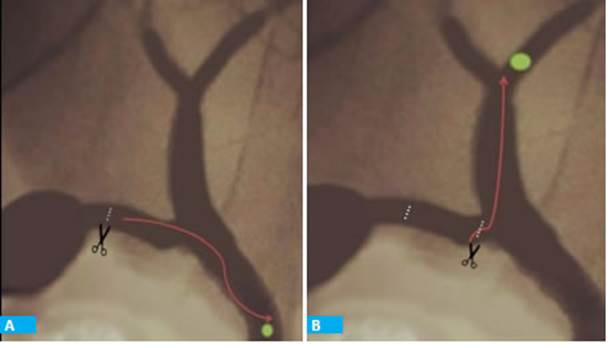

▪▪Favorable cystic duct anatomy: when the cystic duct enters the extrahepatic bile duct from the right lateral aspect and the course is not tortuous. In the absence of this condition, cystic duct anatomy is unfavorable. The cystic duct anatomy may become favorable after further dissection (Fig. 1).

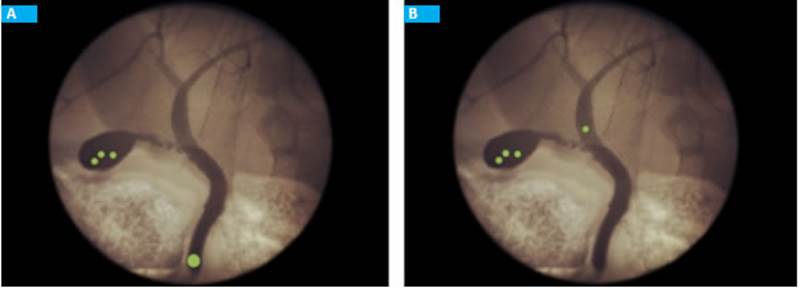

▪▪The relation between cystic duct diameter and gallstone size was defined as > or < 1 using the size of the clamp to estimate the diameter (Fig. 2A).

▪▪Proximal gallstones: presence gallstones proximal to the cystic duct- main bile duct junction (Fig. 2B).

▪▪Unsuspected choledocholithiasis: when gallstones in the common bile duct are identified during IOC in patients with a preoperative diagnosis other than choledocholithiasis.

▪▪Failed transcystic approach: failure to clear gallstones through transcystic exploration, after completing all the available maneuvers to improve efficiency (further dissection, balloon dilation, etc.).

▪▪Total acute main bile duct obstruction syndrome was defined as progressive increase in bilirubin and ALP levels.

▪▪Bile leak: leakage of bile from the abdominal drain placed in the Morrison’s space or need for percutaneous placement of an abdominal drain.

Figure 1 A. Cystic duct with tortuous course (unfavorable anatomy). B. The same case: after further dissection, the Dormia basket could be advanced (favo rable anatomy after maneuvers)

Figure 2 A. Relation between cystic duct diameter and gallstone size < 1. B. Gallstone proximal to the cystic duct-main bile duct junction

Surgical technique

The instruments used included 30° scope, laparoscopic needle holders, K-type 30-35 probes and 5-mm cannulas for the IOC, Dormia baskets with 4 wires, dilation balloons (6 atm, 10 mm × 3 cm), latex Kehr’s T tubes and C-arm fluoroscopic units.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed using the traction maneuver described by Hunter and dissecting until the critical view of safety was achieved. After inserting a clip in the proximal segment of the cystic duct, a cannula was introduced through the 5-mm trocar placed in the right hypochondriac region and K-type 30-35 probes was introduced through the cannula for IOC. A difficult progression of the IOC probe with spontaneous bile output was interpreted as the presence of valves in the cystic duct or a tortuous course4 (anatomical cause). A stone impacted in the cystic duct is also a cause of lack of progression of the probe during IOC but without spontaneous bile output and required maneuvers such as milking the stones before removal5. If the milking maneuver failed or the cystic duct anatomy was unfavorable, further dissection of the distal cystic duct and cysticotomy were repeated to clear the stone or place the cholangiography catheter. In all surgeries, a drain was placed in the Morrison’s space, and was removed 24 hours after surgery in the absence of complications.

Management of choledocholithiasis

Stones < 3 mm were managed with transcystic exploration using Dormia baskets or flushing.

We tried to bring down proximal gallstones with blunt instruments (aspirator, atraumatic forceps) under fluoroscopic guidance; if this maneuver was not successful, the next step was to perform an angled cysticotomy or a minimal choledochotomy to advance the basket to the proximal bile duct. This variant could require minimal bile duct repair (Fig. 3).

When the relation between the cystic duct diameter and gallstone size was < 1 (the gallstone was larger than the cystic duct), the Dormia basket with the gallstone were brought up to the cystic duct and the cysticotomy was extended to facilitate stone extraction. Papillary balloon dilation via a percutaneous transcystic approach is another option to push the stones into the duodenum.

When the transcystic exploration failed we performed laparoscopic choledochotomy in an attempt to clear the stones using the same instruments used for the transcystic exploration. If the gallstones were successfully cleared, antegrade papillary balloon dilation with primary closure of the common bile duct were performed to decrease bile duct pressure and prevent biliary leak. When the papilla was not adequately evacuated or if we were not sure about complete stone clearance, a latex Kehr’s T tube is placed.

Those cases with a large common bile duct (> 15 mm in diameter) with multiple gallstones and a relation between cystic duct diameter and gallstone size < 1 cm were treated with bilio-digestive bypass6. Age is the most used variable to decide between choledochoduodenostomy (> 60 years) or hepaticojejunostomy.

Conversion to open surgery was indicated in those cases of impacted stones in the mid or distal common bile duct without passage of contrast material into the duodenum with impossibility to advance a basket or a guidewire (total acute main bile duct obstruction syndrome).

Results

During the period analyzed, 2447 laparoscopic cholecystectomies were performed, and IOC were carried out in 99.7% of the cases; 416 (17%) presented common bile duct stones.

Preoperative variables

▪▪Most patients were women (275 vs.141) and mean age was 33 years (range 18-88).

▪▪The ASA risk was grade 1 in 158 (38%) patients, grade 2 in 221 (53%) and grade 3 in 37 (9%).

▪▪The diagnoses suspected in 227 (54.5%) patients were jaundice, acute cholangitis, and acute biliary pancrea titis with bile duct dilation.

▪▪In 189 (45.5%) patients the diagnoses were not sus pected and included 72 acute cholecystitis, 70 sympto matic cholelithiasis, 47 acute biliary pancreatitis.

Intraoperative variables

The efficacy of the laparoscopic approach was 99%. Mean operative time was 81 minutes (range 30- 250).

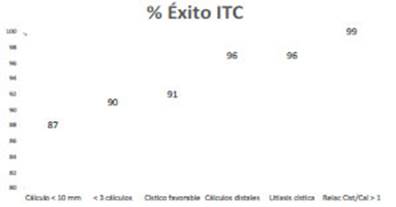

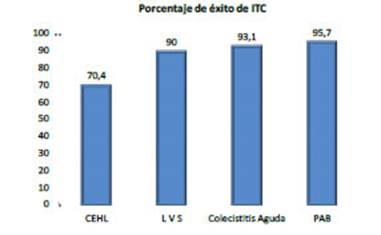

▪▪The global efficacy of the transcystic exploration was 81.2%, with an operative time of 55 minutes and mean length of hospital stay of 24 hours, without complications. The efficacy varied according to the different variables analyzed (Tables 1 and 2, Figures 4 and 5).

▪▪Choledochotomy was necessary in 78 cases (18.75%) with mean operative time of 94 minutes and mean hospital length of stay of 72 hours; 14 patients presented developed (17.9%). Table 3 shows the indication of choledochotomy according to the preoperative diagnosis. After choledochotomy, 34 bile duct repair procedures over a Kehr’s T tube were performed, followed by 24 primary closures of the common bile duct and 20 bilio-digestive bypass procedures (14 choledochoduodenostomies and 6 Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomies).

▪▪Conversion to open surgery was necessary in 4 patients (1.7%), all of them with preoperative diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. The reasons for conversion were multiple adhesions in 2 cases, management of hemostasis and removal of an impacted gallstone in 1 patient with total acute main bile duct obstruction syndrome and need for hepaticojejunostomy in another patient with total acute main bile duct obstruction syndrome.

Postoperative variables

Mean length of hospital stay was 30 hours (range 24-240 hours). There were no deaths or bile duct injuries. Seventeen patients (4%) with preoperative diagnosis of choledocholithiasis developed postoperative complications (Table 4).

▪▪Two patients (0.48%) required reoperation due to bleeding with hemodynamic impairment. Another 4 patients presented bleeding without hemodynamic impairment and were managed with a conservative approach.

▪▪Bile leaks occurred in 8 cases (1.9%); 5 were biliary leaks with favorable outcome with conservative treatment (based on the assessment of drain output) and 3 presented as biloma that required percutaneous treatment. The 8 cases developed after choledocotomies: 5 after bilio-digestive bypass procedures and 3 after primary closure of the common bile duct (without papillary dilation).

▪▪Two patients presented surgical site infection in the umbilicus that was successfully treated with antibiotics.

▪▪Other complications included placement of a nasogastric tube due to vomiting in two patients, and one patient with high preoperative risk and prolonged hospital stay developed pneumonia and required antibiotics.

▪▪Five patients (1.2%) presented residual stones. The diagnosis was made by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and the patients were successfully treated with ERCP.

Discussion

Over the past decades, several prospective randomized trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated the benefits of the one-stage approach for the management of cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis2. Shorter length of hospital stay, lower incidence of complications are lower costs are some advantages observed. Nevertheless, the operative time is longer with the one-stage approach; the procedure requires more sophisticated equipment and trained staff and is not usually paid accordingly. For these reasons, the two-stage approach is most commonly used in daily practice7,8. In our experience, and considering the aforementioned facts, the efficacy of laparoscopy for the treatment of common bile duct stones in a one-stage strategy had an efficacy of 99%. Most cases were successfully treated by transcystic exploration. In line with other reports, the incidence of complications, costs and length of hospital stay were lower when the common bile duct stones were cleared by transcystic exploration than by choledocotomy9.

In our series, the success rate with the trancystic exploration was high (81%) but other studies have shown figures of about 95%2,9,10. This difference could be explained by the exclusion of cases with preoperative diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. The comparison with our previous experience is favorable: the effectiveness of the transcystic exploration improved from 75 to 81%11. This could be due to greater use of maneuvers in case of unfavorable cystic duct anatomy such as further dissection, new cysticotomy, cystic duct lithotomy, cysticotomy over the common bile duct stone, transcystic antegrade papillary dilation and, less frequently, the use of blunting instruments to bring down intrahepatic stones.

The major limitations of the transcystic approach were a relation between the cystic duct diameter and gallstone size < 1, gallstone size > 10 mm and preoperative diagnosis of choledocholithiasis.

Half of the conversions to open surgery in this series were due to an unusual presentation of choledocholithiasis. These patients presented total acute main bile duct obstruction syndrome characterized by jaundice with progressive increase in total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels. The IOC showed a stone usually lodged in the mid or distal common bile duct that completely blocked the passage of dye and of the basket through the trancystic approach or choledocotomy. In many cases, the common bile duct presents a stricture distal to the stone, a situation hardly favorable to solve endoscopically12,13. We believe that these patients may benefit from preoperative ERCP with stent placement, pushing the stone into the dilated area of the bile duct to prevent further impaction, followed by stone clearance through the transcystic approach or choledochotomy. Some authors state that placement of an endoprosthesis may reduce stone size, allowing later clearance of unextractable stones by open surgery or endoscopy14,15. This hypothesis is being evaluated in a prospective randomized trial. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and holmium laser lithotripsy could be another option for these cases16,17.

Conclusions

In non-selected patients with cholelithiasis and common bile duct stones, laparoscopic exploration has an efficacy > 99% when performed by trained operators with adequate instruments.

The efficacy of transcystic exploration in patients without choledocholithiasis is 93% but is significantly reduced in those with choledocholithiasis (70%). The incidence of complications is 0% in those without choledocholithiasis and 7.4% in patients with choledocholithiasis.

We suggest the transcystic approach as the first option to treat common bile duct stones due to the high efficacy of the method and the low rate of complications.

The relation between cystic duct diameter and stone size is the most important predictor of success.

We emphasize the need for training and recommend routine IOC with the primary aim of reducing major bile duct injuries and the secondary aim of solving choledocholithiasis in a single-stage procedure.

Referencias bibliográficas /References

1. Pekolj J. Tratamiento de la litiasis coledociana por vía laparoscó pica. Continúa la controversia. Cir Esp. 2012; 90(3):144-6. [ Links ]

2. Pan L, Chen M, Ji L, et al. The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration combined with cholecystectomy for the management of cholecysto-choledocholithiasis: an up-to-date meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2018; 268(2):247-53. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002731 [ Links ]

3. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical com plications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 pa tients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004; 240:205-13. [ Links ]

4. Turner MA, Fulcher AS. The Cystic Duct: Normal Anatomy and Di sease Processes. Radiographics. 2001; 21(1):3-22. DOI: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja093. [ Links ]

5. Canullán CM, Petracchi EJ, Baglietto NF y col. Modificaciones de la estrategia quirúrgica ante el hallazgo intraoperatorio de litiasis cística. Rev Argent Cirug. 2017; 109(3):129-33. [ Links ]

6. Senthilnathan P, Sharma D, Sabnis S. Laparoscopic choledocho duodenostomy as a reliable rescue procedure for complicated bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2017; 32(4):1828-33. Doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5868-3. [ Links ]

7. Baucom R, Feurer I, Shelton J. Surgeons, ERCP and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: do we need a standard approach for common bile duct stones? Surg Endosc. 2016; 30(2):414-23 DOI 10.1007/s00464-015-4273-z. [ Links ]

8. Wandling M, Hungness E, Pavey E. Nationwide Assessment of Trends in Choledocholithiasis. Management in the United Sta tes from 1998 to 2013. JAMA Surg. 2016; 151(12):1125-30 DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2059. [ Links ]

9. Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Diwakar R. Laparoscopic transcys tic versus transductal common bile duct exploration: a systema tic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2019; 43(8):1935-48 DOI 10.1007/s00268-019-05005. [ Links ]

10. Czerwonko ME, Pekolj J, Uad P, et al. Laparoscopic Transcystic Common Bile Duct Exploration in the Emergency Is as Effec tive and Safe as in Elective Setting. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019; 23(9):1848-55. DOI: 10.1007/s11605-018-4029-x. [ Links ]

11. Chiappetta Porras LT, Nápoli ED, Canullán CM y col. Tratamiento de la coledocolitiasis en un tiempo por videolaparoscopía. Aná lisis de 10 años de experiencia. Cir Esp. 2007; 82(4):231-4 DOI: 10.1016/s0009-739x(07)71712-8. [ Links ]

12. Yasuda I, Itoi T. Recent advances in endoscopic management of difficult bile duct stones. Digest Endosc. 2013; 25:376-85. DOI: 10.1111/den.12118. [ Links ]

13. Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L, et al. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European Society of Gastrointesti nal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2019; 51(5):472-91. DOI: 10.1055/a-0862-0346 [ Links ]

14. Yang J, Peng J, Chen W. Endoscopic biliary stenting for irretrieva ble common bile duct stones: indications, advantages, disadvan tages, and follow-up results. The Surgeon. 2012; 10(4):211-7. Doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.04.003. [ Links ]

15. Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M. Biliary stenting in the man agement of large or multiple common bile duct stones. Gastro intestinal Endoscopy. 2010; 71(7):1200-03.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j. gie.2009.12.055 [ Links ]

16. Petersson U, Johansen D, Montgomery A. Laparoscopic transcys tic laser lithotripsy for common bile duct stone clearance. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015; 25(1):33-6. [ Links ]

17. Varban O, Assimos D, Passman C, et al. Video. Laparoscopic com mon bile duct exploration and holmium laser lithotripsy: a novel approach to the management of common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2010; 24(7):1759-64. [ Links ]

Received: April 22, 2020; Accepted: October 30, 2020

texto en

texto en