Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Lilloa

versión impresa ISSN 0075-9481versión On-line ISSN 2346-9641

Lilloa vol.58 no.1 San Miguel de Tucumán jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.30550/j.lil/2021.58.1/2021.03.25

Lilloa 58 (1): 1-14, 7 de junio de 2021

ARTÍCULO

https://doi.org/10.30550/j.lil/2021.58.1/2021.03.25

Ferns and lycophytes from Ferradura Park, Canela (RS), Brazil

Helechos y licofitas del Parque Ferradura, Canela (RS), Brasil

Falavigna, Tamara J.1* ; Carlos R. Lehn2 ; Marcelo D. Arana3

1Herbário Unilasalle, Universidade La Salle, Av. Victor Barreto, 2288, Canoas - RS, 92010-000, Brasil.

2Docente Curso de Licenciatura em Ciências Biológicas, Instituto Federal Farroupilha - campus Panambi. Rua Erechim 860, Bairro Planalto, Panambi - RS, 9880-000, Brasil.

3Orientación Plantas vasculares, Departamento de Ciencias Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias Exac- tas, Físico-Químicas y Naturales, Instituto ICBIA (UNRC - CONICET), Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto, Ruta 36 km 601, (X5804ZAB) Río Cuarto, Córdoba, Argentina.

* Corresponding author: tfalavigna@gmail.com

Resumen

Se presenta un listado de helechos y licofitas del Parque Ferradura, un parque pri- vado ubicado en Canela, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Posee un área de 400ha y pre senta las formaciones boscosas Bosque de Araucaria, el Bosque Mixto Umbrófilo y el Bosque Deciduo Estacional, con lugares de transición y áreas en diverso estado de regeneración. Hemos encontrado 56 especies (cinco licofitas y 51 helechos) en el Parque Ferradura. Las licofitas están representadas por dos familias (Lycopodiaceae y Selaginellaceae) y cuatro gÉneros, mientras que para helechos se registraron 11 familias y 33 gÉneros. La mayoría de las especies son exclusivamente terrestres (39 especies). La forma de vida predominante son las hemicriptofitas con crecimiento rosulado (27 especies). Phlegmariurus heterocarpon, Polytaenium lineatum y Vittaria linea ta son consideradas especies raras a nivel local. El área presenta el 15% de la riqueza de especies de licofitas y helechos del estado de Rio Grande do Sul, incluyendo las especies raras, lo que resalta la importancia de la implementación de las necesidades de acciones efectivas para la conservación continua del Parque.

Palabras clave: Bosque Atlántico; Lycopodiopsida; Polypodiopsida; Sur de Brasil.

Abstract

A list of ferns and lycophytes from Ferradura Park, a private park located in Canela, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil is presented. The park has an area of 400 ha with forest formations such as Araucaria Forest, Mixed Ombrophilous Forest and Seasonal Deciduous Forest, with transition zones and areas at different stages of regeneration. We found 56 species (five lycophytes and 51 ferns) in Ferradura Park. Lycophytes are represented by two families (Lycopodiaceae and Selaginellaceae) and four genera, while 11 families and 33 genera were recorded for ferns. Most of the species are exclusively terrestrial (39 spp.). The predominant life form is hemicriptophytic with rosulate growth (27 spp.). Phlegmariurus heterocarpon, Polytaenium lineatum and Vittaria lineata are considered locally rare. The area presents 15% of the species richness of the State of Rio Grande do Sul including rare species, which highlights the importance of implementing effective actions for the continuing Park conservation.

Keywords: Atlantic Forest; Lycopodiopsida; Polypodiopsida; Southern Brazil.

Original recibido el , 20 de noviembre 2020

aceptado el 25 de marzo 2021.

Publicado en línea: 5 de abril 2021.

INTRODUCTION

Ferns and lycophytes are plants that grow mainly in humid tropical forests worldwide, in which it represents a very conspicuous group (Tryon & Tryon, 1982; Moran, 2008), being both, lycophytes and ferns, together the second group of vascular plants in number of species. Recent estimates point out the existence of more than 12.000 species of fern and lycophytes (PPG I, 2016), of which 3.500 are found in South America (Moran, 2008), and about 1.300 are found in Brazil (Prado et al., 2015; BFG 2018). In the state of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, 390 species of ferns and lycophytes are registered (Flora do Brasil, 2020). Occupying the most diverse environments in all biomes where they occur (Page, 1979; Moran 2008), ferns and lycophytes are found growing from sea level to almost reach the high mountain vegetation boundary, encompassing semidesert situations (Caatingas, Cerrado), brackish environments (mangroves), tropical pluvial forests (Yungas, Atlantic and Amazonian Forests), pluvial hillsides (Serra of Mantiqueira and the Sea ridges) or even in high mountain regions, as the Andes in South America.

Overall, ferns and lycophytes are most diverse in mountains especially at lower latitudes, where the high environmental heterogeneity harbor a disproportionate number of species (Suissa, Sundue & Testo, 2021), reinforcing the importance of mountains in maintaining tropical fern diversity (Suissa & Sundue, 2020). Particularly, humid forests provide a suitable environment for high abundances and richness of fern and lycophyte species, where these organisms are able to develop in a wide range of biological forms (Senna & Waechter, 1997).

Historically, most studies involving ferns and lycophytes in Rio Grande do Sul were conducted in the Eastern region of the state (Moraes, Marques, Bueno & Lehn, 2018). These studies are focused mainly on the knowledge of the floristic component, and encompassed distinct vegetal formations, including Dense (Burmeister & Schmitt, 2016) and Mixed Ombrophilous Forests (Bueno & Senna, 1992; Schmitt, Fleck, Burmeister & Kieling-Rubio, 2006), as well as Seasonal Forests (Steffens & Windisch, 2007; Lehn, Leuchtenberger & Hansen, 2009; Mallmann & Schmitt, 2014; Padoin, Graeff, Silva & Schmitt, 2015), but still in small number, when compared to similar studies involving angioperms.

The Atlantic Forest (AF) (sensu lato) present one of highest levels of species richness and endemism worldwide (Ribeiro, Metzer, Martensen, Ponzoni & Hirota, 2009), being considered as one of the global hotspots for biodiversity conservation (Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, Fonseca & Kent, 2000). In Rio Grande do Sul state, as observed in different regions of the country, the decreasing process of Atlantic Forest's coverage is still continuous, and the current remnants this domain is estimated at about only the 8% of the original coverage (MapBiomas, 2019), and it is among the most threatened vegetation on earth (Ribeiro et al., 2009).

In this sense, studying forest remnants in the geomorphological region of the Araucaria Plateau (IBGE, 2012) and the Northeast Slope region (Fortes, 1959), which biogeographically composes part of the Parana dominion (Morrone, 2017), is necessary to make feasible the conservation, management and cultivation, for both sustainable economic use and native species conservation, and even aiming the native vegetation recovery.

Therefore, we studied ferns and lycophytes occurring in the Ferradura Park, this park is located in the Araucaria Plateau, which is part of the Atlantic Forest sensu lato (IBGE, 2012), in order to (i) determine the local richness, (ii) characterize the predominant living forms, (iii) determine the preferential substrates and (iv) check the conservation status of species occurring in the study area.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study area

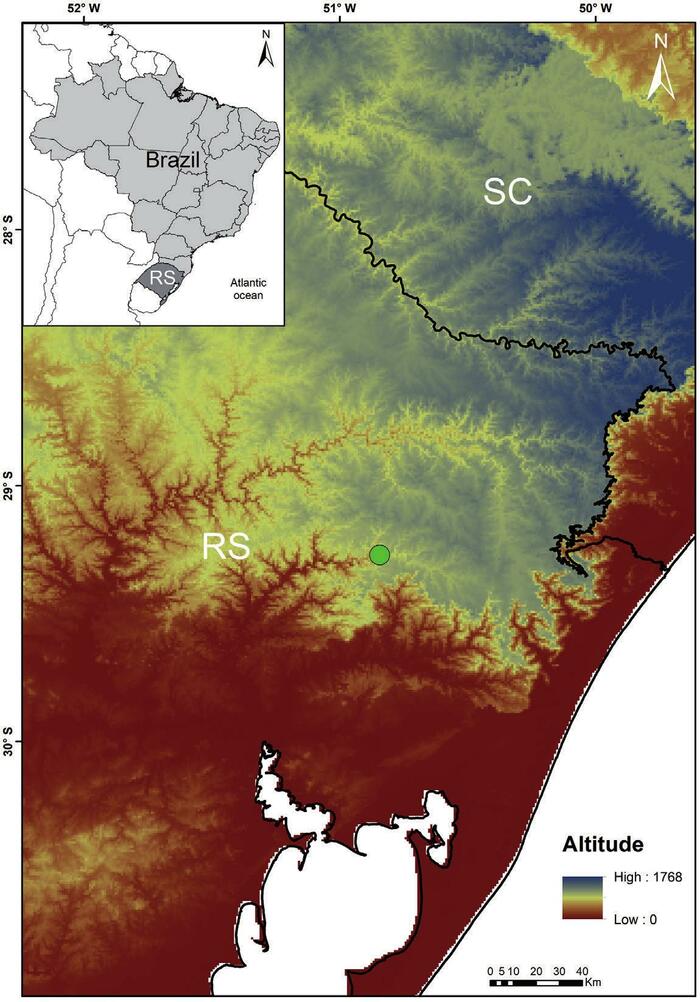

The Ferradura Park (29°16' S - 50°50' W) is located north of Canela municipality, northeast region, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, comprising an area of 400 ha, and varying in altitude from 400 to 750 asl. (Fig. 1). The park is a private property and It presents the forest formations: Araucaria Forest, Mixed Ombrophilous Forest and Seasonal Deciduous Forest (IBGE, 2012), with transition areas between these. The vegetal formations biogeographically are include in the Araucaria Forest province, characterized by Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze (Araucariaceae) forests, typically associated with dense tropical moist forests (with Drimys brasilien sis Miers (Winteraceae), Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil. (Aquifoliaceae), Podocarpus lambertii Klotzsch ex Endl. (Podocarpaceae), and several species of Myrtaceae and Lauraceae), although pure stands also occur. The Araucaria Forest province belongs to the Parana dominion, which corresponds to all the forests east of the Andes and south of the Amazon, originally covered an area of nearly 1,300,000 square kilome ters (Morrone, 2017).

The Ferradura's Park area belongs to the Caí River Basin. In this basin, according to the Fundaçã Estadual de Proteçã Ambiental Henrique Luiz Roessler - FEPAM (1997), there are 11 Conservation Unities, municipal and private, two state CUs - Jacuí Delta State Park and Caracol State Park - and one national park, the Canela National Forest. The region's climate is defined as temperate, without dry season, classified as the subtype Cfa (Peel, Finlayson & McMahon, 2007). There are records of at least three months with average monthly compensated temperatures below 15°C, which causes in the so-called "tropical plants' physiological drought", thus promoting the seasonality (IBGE, 2012).

Fig. 1 Localization of Ferradura Park, in the northeastern region of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil.

Fig. 1 Ubicación del Parque Ferradura, región noreste del Estado de Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

Sampling, herborization and identification

The floristic survey of ferns and lycophytes was carried out between November 2000 and November 2001, during bi-monthly trips, with one revisit, in October 2020. Sampling occurred along preexistent trails, stream banks, trunks of fallen trees, ra vines, clearings, in the edge band and interior of the areas, in order to contemplate different microhabitats. Whenever possible, incursions into the woods were made, at a distance of 50m from the trail, in order to sample all observed specimens, especially the fertile ones, as well as to record habitat data, such as substrate type, life forms and altitude. These specimens constitute the reference collection for plant species determination observed in the Park. The specimens were herborized according to usual techniques for vascular plants (Windisch, 1992) and incorporated to the PACA and SMDB herbaria collections (Thiers, 2017). Specific bibliography was used to identify the taxa, including Prado & Windisch (2000), Arana & Ponce (2015) Dit trich, Salino, Monteiro & Gasper (2017), among others, as well as the morphological comparison with specimens deposited in the herbarium. The conservation status of the species was verified at www.cncflora.jbrj.gov.br (accessed on 27 Sep 2020). The circumscription of families and genera follows PPG I (2016).

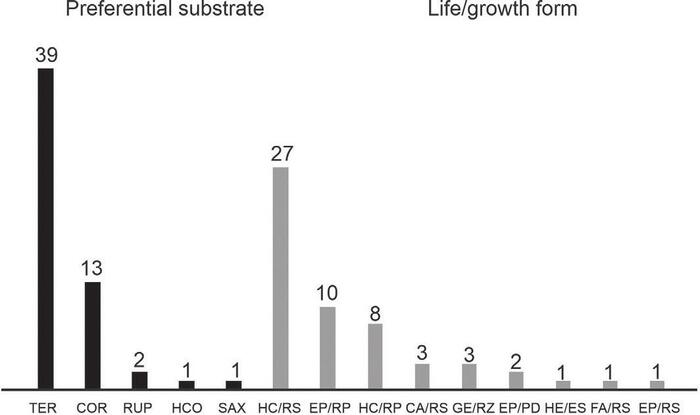

Characterization of life forms and preferential substrate

The species were classified according to the life/growth forms based on Müller-Dombois & Ellenberg (1974) and Senna & Waechter (1997): life/growth form (HC/RS -hemicryptophyte/rosulate, EP/RP - epiphyte/creeping, HC/RP -hemicryptophyte/ creeping, GE/RZ -geophyte/rhizomatous, EP/RS - epiphyte/rosulate, EP/PD -epiphyte/pending, CA/RS - camephyte/rosulate, HE/ES - hemiepiphyte/climbing and FA/RS - phanerophyta/rosulate) and according to the preferential substrate (TER - terrestrial, COR - corticicolous, RUP - rupicolous, SAX - saxicolous and HCO - hemicorticicolous. The species were also classified according to the type of substrate used most frequently, according to proposed in Schmitt et al(2006): i.e.: Corticolous (Cor): exclusively epiphytic species; Hemicorticolous (Hco): species that fix roots and ascend in the phorophyte, but during some period of their existence maintain connection with the soil, that is, exclusively hemiepiphyte; Terrestrial (Ter): species that occur exclusively in the soil; Rupiculate (Rup): occur on bare rock or with a small thickness of soil or humus; Saxicolous (Sax): occur fixed to the substrate accumulated between rocks. In case of occurrence in more than one substrate, it was considered the one with the highest frequency of occurrence.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

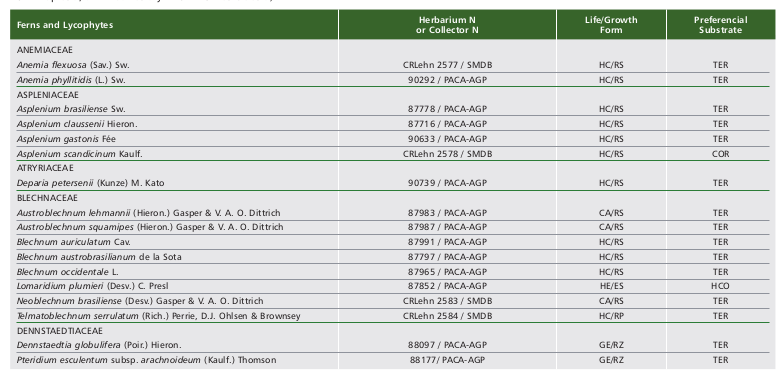

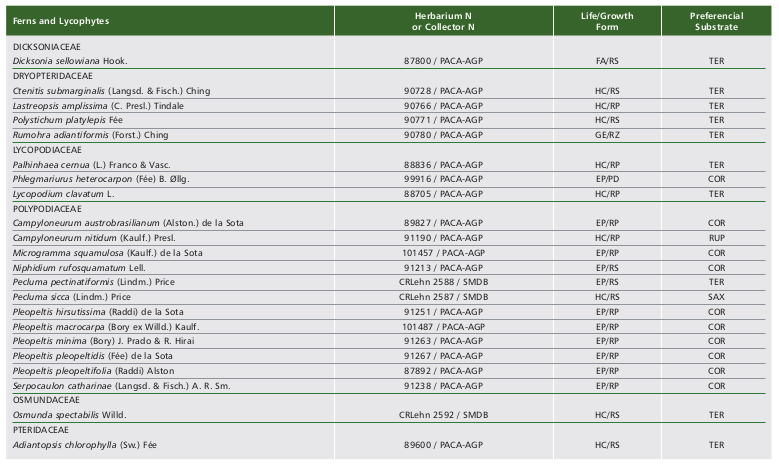

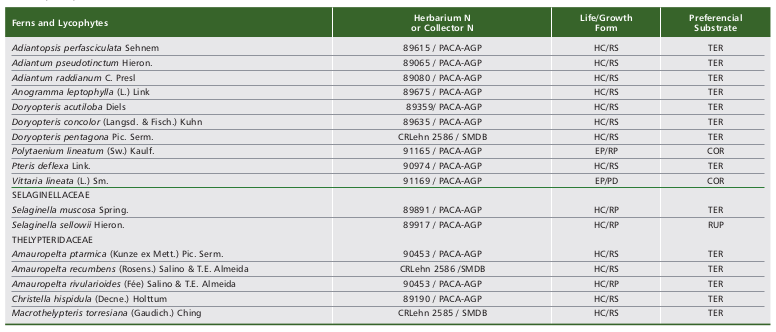

We registered the occurrence of 56 species (five lycophytes and 51 ferns) in the Ferradura Park. The lycophytes are represented by two families (Lycopodiaceae and Selaginellaceae) and four genera, while ferns are represented by 11 families and 33 genera (Table 1, Fig. 2). Polypodiaceae and Pteridaceae showed the highest richness, represented by 12 and 11 species, respectively. Along with Blechnaceae (8 spp.) and Thelypteridaceae (5 spp.), they represent about 65% of species observed in the study area. Pleopeltis Humb. (5 spp.) was the most represented genus, followed by Asplenium L. (4 spp.). Among the observed species, only Dicksonia sellowiana Hook. is listed as endangered (EN), threatened with extinction according to IUCN (2018).

Dicksonia sellowiana (Dicksoniaceae) is a species that occurs widely associated with Ombrophilous Forests (Gasper et al., 2011) in Southern Brazil. Mallmann, Silva & Schmitt (2018) and Silva, Mallmann, Graef, Schmitt & Mehltreter (2019) reported the occurrence of D. sellowiana in ombrophilous forests in RS, presenting great importance in the studied assemblages, occurring in both border and interior of these areas.

Among the 56 species found in this study, three (Phlegmariurus heterocarpon (FÉe) B. Øllg., Polytaenium lineatum (Sw.) Kaulf. and Vittaria lineata (L.) Sm.) were recorded only once, suggesting a very rare occurrence in the study area. Most species observed in the study area are terrestrial (27 spp.) and mainly hemicryptophytes with rosulate growth (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

Polytaenium lineatum (Pteridaceae), distributed from Mexico to South Brazil and Argentina (Nonato & Windisch, 2004; Ponce & Arana, 2016) is a species with rare occurence in the Ferradura Park. This epiphytic species occurs mainly in shaded environments, in the interior of humid forests and is poorly reported in Rio Grande do Sul, where it is only registered in six locations.

Fig. 2 Representative species occurring in Ferradura Park, Canela, RS, Brazil. A) Asplenium gastonis. B) Pleopeltis hirsutissima. C) Osmunda spectabilis. D) Lomaridium plumieri. E) Polystichum platylepis. F) Dicksonia sellowiana.

Fig. 2 Especies representativas presentes en el parque Ferradura, Canela, RS, Brasil. A) Asplenium gastonis. B) Pleopeltis hirsutissima. C) Osmunda spectabilis. D) Lomaridium plumieri. E) Polystichum platylepis. F) Dicksonia sellowiana.

The species richness verified in the Ferradura Park (56 spp.) is similar to the observed in other studies conducted in the northeast region of Rio Grande do Sul, among them Bueno & Senna (1992), Senna & Waechter (1997) and Schmitt et al. (2006), in which the reported richness were 50, 41 and 58 species, respectively. The high representativity of the families Polypodiaceae and Pteridaceae is often reported in floristic studies conducted in Southern Brazil (Silva Jr. & Rörig, 2001; Schmitt et al., 2006; Steffens & Windisch, 2007; Santos & Windisch, 2008; Lehn et al., 2009, and Moraes et al., 2018). These families, along with Dryopteridaceae, are the most representative fern families in Brazil, occupying a wide range of environments in different vegetation types (Prado et al., 2015), Pleopeltis (Polypodiaceae) is represented in the Rio Grande do Sul state by seven species (Flora do Brasil, 2020), six of them registered in the Ferradura Park. The frequent occurrence in fogs, plus the humidity provided by the Caí River Valley, could promote favorable conditions for the occurrence of the species of Pleopeltis in the studied area.

Table 1. Ferns and lycophytes species recorded in Ferradura Park, Canela, RS, Brazil, classified according to the life/growth form (HC/RS -hemicryptophyte/rosulate, EP/ER - epiphyte/creeping, HC/RP -hemicryptophyte/creeping, GE/RZ -geophyte/rhizomatous, EP/RS -epiphyte/rosulate, EP/PD -epiphyte/pending, CA/RS -camephyte/rosulate, HE/ES - hemiepiphyte/climbing and FA/RS - phanerophyte/rosulate) and according to the preferential substrate (TER - terrestrial, COR - corticicolous, RUP - rupicolous, SAX - saxicolous and HCO - hemicorticicolous).

Tabla 1. Especies de helechos y licofitas registrados en el Parque Ferradura Park, Canela, RS, Brasil, clasificados de acuerdo a la forma de vida/crecimiento (HC/RS -hemicriptófita/rosulada, EP/RP - epífita/reptante, HC/RP -hemicriptófita/reptante, GE/RZ -geófita/rizomatosa, EP/RS - epífita/rosulada, EP/PD -epífita/pÉndula, CA/RS - camÉfita/rosulda, HE/ES -hemiepífita/trepadora y FA/RS - fanerófita/rosulada) y de acuerdo al sustrato preferencial (TER - terrestre, COR -corticícola, RUP - rupícola, SAX - saxícola y HCO - hemicorticícola).

The ferns and lycophytes in the Ferradura Park are more frequently terrestrial. However, the two most representative families (Polypodiaceae and Pteridaceae) present distinct preferences for microhabitats occupation. While Polypodiaceae appears to predominate in the epiphytic environment, Pteridaceae was observed occurring widely in the terrestrial substrate. This could contribute to the higher species richness of both families in the study area.

Fig. 3. number of ferns and lycophyte species observed in Ferradura Park, Canela, RS, classified according to the preferential substrate (TER - terrestrial, COR - corticicolous, RUP - rupicolous, SAX - saxicolous e HCO - hemicorticicolous) and according to the life/growth form (HC/RS - hemicryptophyte/rosu late, EP/RP - epiphyte/creeping, HC/RP - hemicryptophyte/creeping, GE/RZ - geophyte/ rhizomatous, EP/RS - epiphyte/rosulate, EP/PD - epiphyte/pending, CA/RS - camephyte/rosulate, HE/ES - hemiepiphyte/climbing and FA/RS -phanerophyta/rosulate).

Fig. 3. Número de especies de helechos y licofitas observados en el Parque Ferradura, Canela, RS, clasificados de acuerdo al sustrato preferencial (TER - terrestre, COR - corticícola, RUP - rupícola, SAX - saxícola, y HCO - hemicorticícola) y de acuerdo a la forma de vida/crecimiento (HC/RS - hemicriptófita/rosulada, EP/RP - epífita/reptante, HC/RP - hemicriptófita/reptante, GE/RZ - geófita/ rizomatosa, EP/RS - epífita/rosulada, EP/PD - epífita/pÉndula, CA/RS - camÉfita/rosulada, HE/ES - hemiepífita/trepadora y FA/RS -fanerófita/rosulada).

The rosulate growth form was observed in about 60% of the species in the Ferradura Park. Under an ecological perspective, the rosulate growth form contributes to a higher efficiency in light energy capturing in the herbaceous stratus (Senna & Waechter, 1997). Additionally, it provides advantages in the nutrient obtaining process, promoting the retention of leaves and thus the removal of nutrients from the plant litter decomposition in the crown of fronds (Zona & Christenhusz, 2015). Although almost all life and growth forms have been observed in the study area, the rosulate hemicryptophytes habit proved to be dominant.

The Ferradura Park houses about 15% of all fern and lycophyte species with recognized occurrence for Rio Grande do Sul. Since the state presents regions with very diverse vegetation characteristics. Thus, the real representativeness of the Park area is larger in relation to species with potential occurrence. The area housing a high richness of ferns and lycophytes species, which together with the presence of rare species, highlights the importance of the preservation of the Ferradura Park, interposing it to the Conservation Units of the Caí River basin.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the administration of the Ferradura Park for allowing access and collection of ferns in the park. We specially thank to Paulo G. Windisch for his orientation in the Master degree of Tamara J. Falavigna.

REFERENCES

Arana, M. D. & Ponce, M. M. (2015). Las Osmundaceae en Argentina, Paraguay y Uruguay. Darwiniana, nueva serie 3 (1): 27-37. [ Links ]

BFG. (2018). Brazilian Flora: Innovation and collaboration to meet Target 1 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation. RodriguÉsia 69 (4): 1513-1527. [ Links ] Bueno, R. M. & Senna, R. M. (1992). Pteridófitas do Parque Nacional dos Aparados da Serra. I. Região do Paradouro. Caderno de Pesquisa, SÉrie Botanica 4 (1): 5-12. [ Links ]

Burmeister, E. L. & Schmitt, J. L. (2016). Species richness and composition of ferns in a fragment of Dense Humid Forest in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Pesquisas Botânica 69: 157-168. [ Links ]

Dittrich, V. A. O., Salino A., Monteiro R. & Gasper, A. L. (2017). The family Blechnaceae (Polypodiopsida) in Brazil: key to the genera and taxonomic treatment of Austroblechnum, Cranfillia, Lomaridium, Neoblechnum and Telmatoblechnum for southern and southeastern Brazil. Phytotaxa 303: 1-33. [ Links ]

FEPAM. (1997). Levantamento dos principais usos do solo e da água na bacia hidrográfica do rio Caí. Vol. 1. Projeto FEPAM / GTZ - Cooperaçã TÉcnica Brasil/Alemanha, Porto Alegre.

Flora do Brasil (2020) em construçã. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br.

Fortes, A. B. (1959). Geografia Física do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre: Ed. Globo. [ Links ]

Gasper, A. L., Savegnani, L., Vibrans, A. C., Uhlmann, A., Lingner, D. V., Verdi, M., Dreveck, S., Stival-Santos, A., Brogni, E., Schmitt, R. & Kelmz, G. (2011). Inventário de Dicksonia sellowiana Hook. em Santa Catarina. Acta Botanica Brasilica 25 (4): 776-784. [ Links ]

IBGE. (2012). Manual TÉcnico da Vegetaçã Brasileira. 2ª ed. Rio de Janeiro. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv63011.pdf.

IUCN. (2018). www.iucnredlist.org. [ Links ]

Lehn, C. R., Leuchtenberger, C. & Hansen, M. A. (2009). Pteridófitas ocorrentes em dois remanescentes de Floresta Estacional Decidual no Vale do Taquari, Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Iheringia SÉrie Botânica 64: 23-31. [ Links ]

Mallmann, I. T. & Schmitt, J. L. (2014). Riqueza e composiçã florística da comunidade de samambaias na mata ciliar do Rio Cadeia, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Ciência Florestal 24 (1): 97-109.

Mallmann, I. T., Silva, V. L. & Schmitt, J. L. (2018). Inventory of ferns and lycophytes within forest fragments of Araucaria in southern Brazil. Biota Neotropica 18 (4): 1-19. [ Links ]

MapBiomas. (2019). Projeto de Mapeamento Anual da Cobertura e Uso do Solo no Brasil. https://mapbiomas.org/colecoes-mapbiomas-1?cama_set_language=pt-BR. [ Links ]

Moraes, G. O. de, Marques, M. W., Bueno, M. L. & Lehn, C. R. (2018). Samambaias e licófitas da sub-bacia do Rio Fíuza, noroeste do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Pesquisas Botânica 71: 97-107. [ Links ]

Moran, R. C. (2008). Diversity, biogeography and floristics. In: T. A. Ranker. & C. H. Haufler (Eds.), Biology and evolution of ferns and lycophytes (pp. 367-394). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. (2017). Neotropical biogeography: Regionalization and evolution. Boca Raton. 1st. Ed. Estados Unidos: CRC Press. [ Links ]

Müller-Dombois, D. & Ellenberg, G. H. (1974). Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. New York: Wylley e Sons. [ Links ]

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Fonseca, G. A. & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403 (6772): 853-858. [ Links ]

Nonato, F. R. & Windisch, P. G. (2004). Vittariaceae (Pteridophyta) do Sudeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 27 (1): 149-161. [ Links ]

Padoin, T. O. H., Graeff, V., Silva, V. L. & Schmitt, J. L. (2015). Florística e aspectos ecológicos das samambaias e licófitas da mata ciliar de um afluente do Rio Rolante no Sul Do Brasil. Pesquisas Botânica 68: 335-348. [ Links ]

Page, C. N. (1979). The diversity of ferns. An ecological perspective. In: A. F. Dyer. The experimental biology of ferns (pp. 9-56). London: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). Updated world map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Science 11: 1633-1644. [ Links ]

Ponce, M. M. & Arana, M. D. (2016). Polytaenium. In: M. M. Ponce, M. D. Arana (Coords.), Flora vascular de la República Argentina 2 (pp. 340-341). [ Links ]

PPG I. (2016). A community derived classification for extant lycophytes and ferns. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 54 (6): 563-603. [ Links ]

Prado, J. & Windisch, P. G. (2000). The genus Pteris L. (Pteridaceae) in Brazil. Boletim do Instituto de Botânica 13: 103-199. [ Links ]

Prado, J., Sylvestre, L. S., Labiak, P. H., Windisch, P. G., Salino, A., Barros, I. C. L., Hirai, R. Y., almeida, T. E., Santiago, A. C. P., Kieling-Rubio, M. A, Pereira, A. F. N., Øllgaard, B., Ramos, C. G. V., Mickel, J. T., Dittrich, V. A. O., Mynssen, C. M., Schwartsburd, P. B., Condack, J. P. S., Pereira, J. B. S. & Matos, F. B. (2015). Diversity of ferns and lycophytes in Brazil. RodriguÉsia 66: 1-12. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, M. C., Metzer, J., P., Martensen, A. C., Ponzoni, F. J. & Hirota, M. M. (2009). The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: how much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation 142: 1141-1153. [ Links ]

Santos, A. C. C. & Windisch, P. G. (2008). Análise da pteridoflora da área de proteçã ambiental do Morro da Borússia (Osório-RS). Pesquisas Botânica 59: 237-252.

Schmitt, J. L., Fleck, R., Burmeister, E. L. & Kieling-Rubio, M. A. (2006). Diversidade e formas biológicas de pteridófitas da Floresta Nacional de Canela, Rio Grande do Sul: contribuições para o plano de manejo. Pesquisas Botânica 57: 275-288. [ Links ]

Senna, R. M. & Waechter, J. L. (1997). Pteridófitas de uma floresta com araucária. 1. Formas biológicas e padrões de distribuiçã geográfica. Iheringia, SÉrie Botânica 48: 41-58.

Silva Jr, A. & Rörig, J. F. S. (2001). Estudo florístico-ecológico das pteridófitas da localidade de Picada Verão, Sapiranga-RS. Pesquisas Botânica 51: 137-145. [ Links ]

Silva, V. L., Mallmann, I. T., Graeff, V., Schmitt, J. L. & Mehltreter, K. (2019). Phytosociological contrast of ferns and lycophytes from different surroundings matrices in Southern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology 79 (3): 495-504. [ Links ]

Steffens, C. & Windisch, P. G. (2007). Diversidade e formas de vida de pteridófitas no Morro da Harmonia em Teutônia-RS, Brasil. Pesquisas, Botânica 58: 375-382. [ Links ]

Suissa, J. S. & Sundue, M. A. (2020). Diveristy Patterns of Neotropical Ferns: Revisitng Tryon's Centers of Richness and Endemism. American Fern Journal 110 (4): 211-232. [ Links ]

Suissa, J. S., Sundue, M. A. & Testo, W. L. (2021). Mountains, climate and niche heterogeneity explain global patterns of fern diversity. Journal of Biogeography (00): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14076. [ Links ]

Thiers, B. (2017). Index Herbariorum: a global directory of public herbaria and associated staff. New York Botanical Garden's Virtual Herbarium. http://sweetgum.nybg.orh/ih/. [ Links ]

Tryon, R. M. & Tryon, A. F. (1982). Ferns and allied plants with special reference to tropical America. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Windisch, P.G. (1992). Pteridófitas da região norte-ocidental do estado de São Paulo: guia para estudo e excursões. São JosÉ do Rio Preto: Universidade Estadual Paulista - UNESP. [ Links ]

Zona, S. & Christenhusz, M. J. M. (2015). Litter-trapping plants: filter-feeders of the plant kingdom. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 179: 554-586. [ Links ]