Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Compartir

Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales

versión On-line ISSN 1853-0400

Rev. Mus. Argent. Cienc. Nat. vol.17 no.1 Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires jun. 2015

PALEONTOLOGÍA

On the presence of Nasua Storr (Carnivora, Procyonidae) in the Buenos Aires province in the late Holocene

Mariano A. Ramírez1, Francisco J. Prevosti1,2, Alejandro Acosta3, Natacha Buc3 & Daniel Loponte3

1 División Mastozoología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "Bernardino Rivadavia", Angel Gallardo 470, C1405DJR, Buenos Aires, Argentina. ma_ramirezchicco@macn.gov.ar; protocyon@hotmail.com

2 Departamento de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad Nacional de Luján, Luján, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

3 CONICET- Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano, 3 de Febrero 1378, C1426BJN, Buenos Aires, Argentina. acosta@retina.ar; natachabuc@gmail.com; dloponte@inapl.gov.ar

Abstract

The genus Nasua is represented by two species, Nasua nasua and Nasua narica. Its current distribution spans from the south of North America to the north of the Rio Negro in Uruguay. Both species of the genus inhabit a great number of forested habitats. In Argentina, the species Nasua nasua is found in Tucuman, Jujuy, Chaco, Formosa and the northeast of Santa Fe. In the present contribution we describe a lower canine of Nasua nasua from the late Holocene of the Arroyo Fredes archaeological site, in the Parana's Delta, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, which is outside the current distribution of this species. We compared the canine with several specimens of Nasua nasua both males and females. Given the strong sexual dimorphism observed in the canines of this species, we recognized the specimen as a male. Two hypotheses can explain the presence of this specimen in the Parana's Delta of Buenos Aires: (1) Current and past climatic similarities between the southernmost record of the species and the Arroyo Fredes archeological site, and the corridor effect caused by the gallery forests. (2) Human transport by the guaranies.

Keywords: Nasua; Procyonidae; Parana's delta; Late Holocene.

Resumen

Sobre la presencia de Nasua Storr (Carnivora, Procyonidae) en la provincia de Buenos Aires en el Holoceno tardío

El género Nasua está compuesto por dos especies, Nasua nasua y Nasua narica. Se distribuye en la actualidad desde el sur de América del Norte hasta el norte del Río Negro en Uruguay. Ambas especies habitan un gran número de ambientes arbolados. En Argentina la especie Nasua nasua se encuentra en Tucumán, Jujuy, Chaco, Formosa y el Noreste de Santa Fe. En esta contribución describimos un canino inferior de Nasua nasua del Holoceno tardío del Sitio Arqueológico Arroyo Fredes en el Delta del Paraná de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina, que se encuentra por fuera de la distribución actual de la especie. Comparamos el canino con varios especímenes de Nasua nasua, tanto machos como hembras. Dado el fuerte dimorfismo sexual observado en los caninos, pudimos reconocer al espécimen como un macho. Dos hipótesis pueden explicar la presencia de este espécimen en el Delta del Paraná de Buenos Aires (1) Las similitudes entre las condiciones climáticas actuales y en el pasado entre la localidad actual más cercana y el sitio arqueológico Arroyo Fredes y el efecto corredor causado por los bosques en galería. (2) Transporte humano por los guaraníes.

Palabras clave: Nasua; Procyonidae; Delta del Parana; Holoceno tardío.

INTRODUCTION

The genus Nasua Storr is represented by two species, the white-nose coati (Nasua narica Linnaeus) and the South American Coatí (Nasua nasua Linnaeus) (Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009). Nasua narica is currently distributed in the south of North America, Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador, while Nasua nasua is found in South America from Colombia and Venezuela to Uruguay (Gompper, 1995; Gompper & Decker, 1998; Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009). In Argentina, it is found in Tucuman, Jujuy, Chaco, Formosa and the northeast of Santa Fe (Gompper & Decker, 1998; Pautasso, 2008, Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009; Barquez et al., 2006; Cannevari & Vaccaro, 2007).

The first appearances for the genus were recorded in North America in the Late Miocene of Florida (Baskin, 1988) and the Early Pliocene of Texas (Dalquest, 1978; Baskin, 1998). In South America its record is limited to one specimen from the Late Pleistocene of Minas Gerais, Brazil (Gervais & Ameghino, 1880) and one specimen, referred as cf. Nasua (Hoffstetter, 1963) from the Ensenadan of Tarija, Bolivia, with an unclear stratigraphic provenance (Marshall et al., 1984; Hoffstetter, 1986).

In the present contribution, we describe the first record of Nasua and the species N. nasua from the Delta of the Parana River, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. We provide alternative hypotheses explaining this finding outside the current distribution of the species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We compared the fossil specimen (INAPL-AF2, Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano) with 23 specimens of Nasua nasua deposited in the Division of Mastozoologia from the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "Bernardino Rivadavia". We measured the 23 specimens of Nasua nasua, both male and females, and a specimen of Nasua narica, using a digital caliper of 0.01 mm. The measurements taken were the length (Lc1), width (Wc1) and height (Hc1) of the lower canine (Supplementary data 1). We plotted the measurements in a scatter plot graph to illustrate the determination of the sex of INAPL-AF2.

We compared the different bioclimatic conditions (supplementary data 2) obtained from the latest historical (not fossil) databases (Hijmans et al., 2005) for the southernmost location where Nasua nasua is recorded at the Rio Negro river, Uruguay, and the Arroyo Fredes archaeological site, Buenos Aires, Argentina. A similar analysis was made using the bioclimatic conditions suggested for the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (Collins et al., 2004).

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Order Carnivora Bowdich, 1821

Family Procyonidae Gray, 1825

Genus Nasua Storr, 1780

Type species. Viverra nasua Linnaeus, 1766.

Nasua nasua (Linnaeus, 1766)

Figs. 2.A-D, 4.A-B

Fig. 2. INAPL-AF2. A, lingual; B, labial; C, mesial and D, distal views. Scale bar equal 5 mm.

Studied material. An isolated left lower canine (INAPL-AF2) (Fig. 2.1-4).

Stratigraphic and geographic provenance. Arroyo Fredes Archaeological site (34° 13' 50,70'' S 58° 23' 32,52'' W), San Fernando, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A, map showing the location of the Arroyo Fredes archaeological site. B, stratigraphic column of the Arroyo Fredes archaeological site.

The Arroyo Fredes archaeological site is located on a fluvial bank in the island sector of the San Fernando district, which belongs to Delta and Paraná Islands ecoregion (sensu Burkart et al., 1999). The archaeological site was formed by Amazonian horticulturalist groups, historically known as guaraníes (Loponte & Acosta, 2003-2005). The archaeological record includes pottery, lithic artifacts, faunal remains and primary human burials. All these materials were arranged in the 10-35cm thickness current soil horizon (horizon A). Underneath, the C horizon is composed by a substratum of fluvial sands and clays, which was the basis for the development of fluvial banks and is sterile in archaeological materials. Three radiocarbon dates show a temporal range from 690-370 14C years BP for this occupation (see Loponte et al., 2011 for details). INAPL-AF2 was recovered in the digging unit 6 (DU6). A capybara (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris) bone fragment from DU6 was dated in 402 ± 40 14C years BP (δC13 -12 ‰) 1431-1525 years AD (AA 77309; calibrated according to Fairbanks et al., 2005; see Loponte et al., 2011). INAPL-AF2 comes from an archaeofaunal context together with marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus), capybara (H. hydrochaeris), coypus (Myocastor coypus) and fishes (Characiformes and Siluriformes) (Acosta & Mucciolo, 2009; Musali, 2010; Loponte et al., 2011). All these taxa are typical from the insular sector of Paraná Delta present in the area since 2500 years BP, suggesting an ecological situation similar to the current one (Loponte et al., 2012).

Description. The specimen is a complete left lower canine with a high degree of wear in its distal margin, which forms a strong vertical facet. The canine presents one cusp and one root and it is subtriangular in cross-section. Its crown is high and narrow with two grooves on its labial and lingual sides. A shallow labial groove extends on the lower half of the canine. The lingual groove is deeper and extends to the tip of the tooth. The root also presents two shallow lateral grooves which run longitudinally on the lingual and labial sides. These lateral grooves are independent from the grooves of the crown. The enamel occupies half of the tooth length, except in the mesial side of the crown where it occupies less than the half of the tooth length.

DISCUSSION

The morphology of INAPL-AF2 with its subtriangular outline and the labial and lingual lateral grooves is coincident with the features observed in the specimens of the genus Nasua. Among other procyonids, grooved canines were mentioned in the Potosinae (Ahrens, 2012; Decker & Wozencraft, 1991). In Potos and Bassaricyon both labial and lingual grooves can be observed (Ahrens, 2012). However both species are considerably smaller than Nasua nasua. Also, the canines of both species show a rounded cross-section. The canines of Nasuella olivacea are grooved as in the genus Nasua (Ahrens, 2012) but this species is characterized for being smaller than Nasua (Hollister, 1915). Other orders of carnivoran mammals have conical lower canines that are subelliptical in cross-section and the grooves on the crown, when present, are shallower than the grooves of Nasua. The crowns of the upper canines of Nasua are flat in cross-section and the base of the crown is wider than the tip which gives the element a triangular shape. Lower canines of Nasua are subtriangular in cross-section and the crown is mesially curved and distally straight. The morphology of INAPL-AF2 is coincident with the morphology of the lower canines of Nasua. The size of the element is in the range of the size of the specimens of Nasua nasua here measured (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Biplots of the linear measurements obtained from the specimens of Nasua nasua, Nasua narica and INAPL-AF2 showing the distinction between males and females and the position of the fossil among them. A, length of the canine (horizontal axis) vs. width of the canine (vertical axis); B, height of the canine (horizontal axis) vs. width of the canine (vertical axis).

Nasua nasua shows a strong sexual dimorphism with the females smaller than the males (Gompper & Decker, 1998). The anatomy of the lower canines differs between sexes: in the males it is tall with two distinct longitudinal grooves on the labial and lingual sides of the crown; while in the females, it is lower than in the males with a shallower labial groove. The specimen described here is coincident with the morphology observed in the males of Nasua nasua. The size of INAPL-AF2 is coincident with the size of the males of Nasua nasua (Fig. 3).

The distinction between Nasua nasua and Nausa narica is based on characters of the pelage (white muzzle pelage in Nasua narica and brown of grey in N. nasua), palate (depressed along the midline in Nasua narica and flat in N. nasua) and the nasal bones (the sides of the nasal bones are parallel and not converge posteriorly in Nasua narica and converging posteriorly in N. nasua) (Gompper & Decker, 1998; Gompper, 1995). Both species are similar in size and the degree of sexual dimorphism (Gompper & Decker, 1998; Gompper, 1995). The morphology of the lower canine is similar in Nasua nasua and Nasua narica and we cannot discriminate both species on the basis of this element (Gompper, 1995). Considering that Nasua narica is restricted to Central and North America and the Northwestern part of South America (Colombia and Ecuador) (Gompper, 1995; Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009) we suggest that INAPL-AF2 could tentatively correspond to Nasua nasua given its current distribution (Gompper, 1995; Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009).

Nasua nasua inhabits a great number of forested habitats including rainforest, cloud forest, xeric Chaco, dry scrub forest and gallery forest from Colombia and Venezuela, reaching Uruguay, the south of Brazil, and the north part of Argentina (Gompper and Decker, 1998; Pautasso, 2008; Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009). Its austral limit is the Rio Negro River, Uruguay (González & Martínez-Lafranco). INAPL-AF2 was collected in the zone of the Paraná River delta and it represents the first record of Nasua nasua in the Buenos Aires province. The distance between the Arroyo Fredes archaeological site and the southernmost record of the species in Argentina is ca. 1000 Km (Gompper & Decker, 1998; Pautasso, 2008; Wilson & Mittermeier, 2009; Barquez et al., 2006; Cannevari & Vaccaro, 2007). However, this archaeological site is ca. 100 km from the southernmost record of the species considering its current distribution, in the north of Rio Negro River in Uruguay (González & Martínez-Lafranco, 2010).

Two hypotheses can explain the presence of Nasua in the Delta Region of Buenos Aires: (1) climatic or (2) human causes. Similarities between current and past (at least for the LGM) climatic conditions recorded in the joint of the Rio Negro and Uruguay rivers in Uruguay and the Arroyos Fredes archaeological site (compared using the databases from Hijmans et al., 2005 and Collins et al., 2004; Supplementary data 2), the short distance between both localities, and the effect of corridor caused by the gallery forests of the Parana Uruguay rivers (Fracassi et al., 2010; Bo et al., 2002) makes likely the presence of Nasua nasua in the Paraná Delta. Contemporary ecological conditions in the Paraná Delta were already established by 2300 years ago, according to the material recorded from the non-ceramic level of Islas Lechiguanas archaeological site (Loponte et al., 2012). Archaeofaunal record until the XVI century, including that from the Arroyo Fredes, does not show different compositions which can sustain climate changes (Acosta, 2005; Loponte, 2008; Arrizurieta et al., 2010; Loponte et al., 2011). However, during the Late Holocene, in particular between 700-400 years BP, more humid conditions where registered in the Pampean region and in South Eastern Uruguay, which was correlated with the Medieval Warm Period (Tonni et al., 1999; Tonello & Prieto, 2010; Stutz et al., 2006; Del Puerto et al., 2011). Warmer and more humid climatic conditions as a product of the MWP could have favored the presence of Nasua in the Parana River delta.

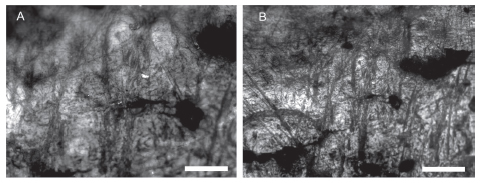

On the other hand, the presence of N. nasua in Arroyo Fredes also can be explained by anthropic activities. It is known that the Uruguay River was one of the main venues for Amazonian horticultural groups, which peopled the Paraná Delta and the upper estuary of the Río de la Plata (Loponte et al., 2011). The distribution of N. nasua greatly overlaps that of the guaraní archaeological record, and therefore human transport could be a possible factor to explain the presence of the tooth in the area under study. In addition, ethnographic information indicated that the historic guaraníes captured and tamed coatis (Azara, 1802; Remorini, 2009). Teeth handling is a behavior well documented in different hunter-gatherer groups of the Low Paraná wetland (Acosta et al., 2013). However, the specimen under study does not show macroscopic, intentional modifications. Analyzed under high magnifications, the enamel of the canine has a particular microwear formed by narrow, superficial and smooth striations disposed in a crossed multidirectional pattern (Fig. 4). Similar microwear was experimentally obtained in bone items simulating transport and manipulation (cf. D'Errico, 1993). Faunal teeth and other anatomic units were recorded as amulets in many hunter-gatherer contexts, being their meaning related to utilitarian and symbolic factors. Frequently, as can be the case under study, these items are not modified but set aside, conserved and transported among people (see Acosta et al., 2013 for a detailed discussion).

Fig. 4. INAPL-AF2 Metallurgical microscope: narrow, superficial and smooth striations disposed in crossed multidirectional pattern. Scale bars equal: 100 μ and 50 μ respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

The specimen described here (INAPL-AF2) can be assigned to the genus Nasua. Given the current distribution of the species of Nasua (Nasua narica and Nasua nasua) we tentatively assigned the specimen to the species Nasua nasua. INAPL-AF2 represents the first record of Nasua in the Buenos Aires Province and the southernmost record of the genus. The current and past climatic similarities between the Rio Negro in Uruguay and the Arroyo Fredes archeological site, and the corridor effect caused by the gallery forests in the Paraná River delta can explain the presence of Nasua in the Buenos Aires province. On the other hand, its presence in the site can be explained by human transport by the guaranies. With the current evidence both hypotheses are equally likely and further evidence is needed to clarify this issue.

Supplementary data 1. List of specimens measured to perform the cuantitative comparissons of size and sex determination.

Supplementary data 2.Comparisson of the bioclimatic information obtained from the data bases for A) the present and B) the LGM. Horizontal axis: North of Rio Negro river, Uruguay. Vertical Axis: Arroyo Fredes, Argentina. Bio1= Annual Mean Temperature. Bio3= Isothermality. Bio5= Max Temperature of Warmest Month. Bio6= Min Temperature of Coldest Month. Bio12= Annual Precipitation. Bio15= Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation). b: indicates the slope of the function. Temperatures are expressed in °C X 10. Precipitations are expressed in mm.

AKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Isabel Vilanova for helping us in finding part of the bibliography. We thank S. Echarri for his helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Mauro Schiaffini for his help with the paleoclimatic data. Part of this research was funded by PICT-2012-1261; PICT2011-2035; PIP2012-11220110100565.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Acosta, A. 2005. [Zooarqueología de cazadores-recolectores del extremo nororiental de la provincia de Buenos Aires (humedal del río Paraná inferior, Región Pampeana, Argentina). PhD Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, UNLP. [ Links ]]

2. Acosta, A. & L. Mucciolo. 2009. Zooarqueologia dos grupos horticultores amazonicos no rio Parana inferior: o caso do sitio Arroyo Fredes. Revista de Arqueología, Sociedad Brasileira de Arqueología 22: 43-63. [ Links ]

3. Acosta, A., N. Buc, M.A. Ramirez, & F.J. Prevosti. 2013. Objetos ornamentales elaborados sobre caninos de carnívoros por grupos cazadores recolectores del humedal del Paraná inferior. Paper at III Congreso Nacional de Zooarqueología Argentina. Tilcara, Jujuy. [ Links ]

4. Ahrens, H.E. 2012. Craniodental characters and the relationships of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carnivora). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 164: 669-713. [ Links ]

5. Arrizurieta, M. P., L. Mucciolo & J. Musali. 2010. Análisis arqueofaunístico preliminar del sitio Cerro Lutz. In: M. Berón, L. Luna, M. Bonomo, C. Montalvo, C. Aranda & M. Carrera Aizpitarte (eds.). Mamül Mapu: pasado y presente desde la arqueología pampeana, Tomo I. Editorial Libros del Espinillo, Ayacucho, p. 335-348. [ Links ]

6. Azara, F. de. 1802. Apuntamientos para la Historia Natural de los cuadrúpedos del Paraguay y Río de la Plata. Tomo Segundo. Imprenta de la Viuda de Ibarra, Madrid, 328 p. [ Links ]

7. Barquez, R.M., M.M. Díaz & R.A. Ojeda. 2006. Mamíferos de Argentina. Sistemática y Distribución. Sarem, Tucumán, 359 p. [ Links ]

8. Baskin, J.A. 1998. Procyonidae. In: C.M. Janis, K.M. Scott & L.L. Jacobs (eds.), Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America.Volume 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 143-151. [ Links ]

9. Bo, R.F., F.A. Kalesnik & R.D. Quintana. 2002. Flora y fauna silvestres de la porción terminal de la Cuenca del Plata. Consideraciones ecológicas y biogeográficas. In: J.M. Borthagaray (ed.). El Río de la Plata como Territorio. Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo - UBA y Ediciones Infinito, Buenos Aires, p. 99-124. [ Links ]

10. Bowdich, T.E. 1821. An Analysis of the Natural Classifications of Mammalia for the Use of Students and Travelers. J. Smith, Paris, 115 p. [ Links ]

11. Burkart, R., N. Bárbaro, R. Sánchez & D. Gómez. 1999. Ecoregiones de la Argentina. Administración de Parques Nacionales. Programa de Desarrollo Institucional Ambiental. Secretaría de Recursos Naturales y Desarrollo Sustentable, 43 p. [ Links ]

12. Canevari, M. & O. Vaccaro. 2007. Guía de Mamíferos del Sur de América del Sur. L.O.L.A., Buenos Aires, 414 p. [ Links ]

13. Collins, W.D., M. Blackmon, C. Bitz, G. Bonan, C.S. Bretherton, J.A. Carton , P. Chang, S.C. Doney, J.J. Hack, T.B. Henderson, J.T. Kiehl, W.G. Large, D.S. McKenna, B.D. Santer & R.D. Smith. 2004. The community climate system model: CCSM3. Journal of Climate 19: 2122-2143. [ Links ]

14. Dalquest, W.W. 1978. Early Blancan mammals of the Beck Ranch local fauna of Texas. Journal of Mammalogy 59: 269-298. [ Links ]

15. Decker, D.M. & Wozencraft, W.C. 1991. Phylogenetic analysis of recent procyonid genera. Journal of Mammalogy 72: 42-55. [ Links ]

16. D'Errico, F. 1993. La vie sociale de l'art mobilier paléolithique. Manipulation, transport, suspension des objets en os, bois de cervidés, ivoire. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 12: 145-174. [ Links ]

17. Del Puerto, L., F. García Rodríguez, R. Bracco, C. Castiñeira, A. Blasi, H. Inda, N. Maseo & A. Rodriguez. 2011. La evolución climática holocénica para el Sudeste de Uruguay. Análisis multiproxy en testigos de lagunas costeras. In: F. García Rodríguez (ed.). El Holoceno en la zona costera de Uruguay, Universidad de la República, Uruguay, p. 117-147. [ Links ]

18. Fairbanks, R.G, R.A. Mortlock, T-C. Chiu, L. Cao, A. Kaplan, T.P. Guilderson, T.W. Fairbanks & A.L. Bloom. 2005. Marine Radiocarbon Curve Spanning 10,000 to 50,000 years B.P. Based on Paired 230Th/234U/ 238U and 14C Dates on Pristine Corals. Quaternary Science Reviews 24: 1781-1796. [ Links ]

19. Fracassi, N.G., P.A. Moreyra, B. Lartigau, P. Teta, R. Landó & J.A. Pereira. 2010. Nuevas especies de mamíferos para el bajo delta del paraná y bajíos ribereños adyacentes, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Mastozoología neotropical 17: 367-373. [ Links ]

20. Gervais, P. & F. Ameghino. 1880. Les mammiferes fossils de l'Amérique du Sud. In: Ameghino Obras II, p. 512-645. [ Links ]

21. Gompper, M.E. 1995. Nasua narica. Mammalian species 487: 1-10. [ Links ]

22. Gompper, M.E. & Decker, D. M. 1998. Nasua nasua. Mammalian Species 580: 1-9. [ Links ]

23. González, E.M. & J.A. Martínez-Lanfranco. 2010. Mamíferos de Uruguay. Guía de campo e introducción a su estudio y conservación. Vida Silvestre - Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. Ediciones de la Banda Oriental, Montevideo, 462 p. [ Links ]

24. Gray, J.E. 1825. Outline of an attempt at the disposition of the Mammalia into tribes and families with a list of the genera apparently appertaining to each tribe. Annalia Philosophica New Series 10: 337-334. [ Links ]

25. Hijmans, R.J., S.E. Cameron, J.L. Parra, P.G. Jones & A. Jarvis. 2005. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 25: 1965-1978. [ Links ]

26. Hoffstetter, R. 1963. La faune Pleistocène deTarija (Bolivie), note preliminaire. Bulletin Muséum National d ́ Histoire Naturelle 35: 194-203. [ Links ]

27. Hofstetter, R. 1986. High Andean mammalian faunas during the Plio-Pleistocene. In: F. Vuilleumier & M. Monasterio (eds.), High altitude tropical biogeography, Oxford University, Oxford, p. 218-245. [ Links ]

28. Hollister, N. 1915. The genera and subgenera of raccoons and their allies. Proceedings of the United States National Museum 49: 143-150. [ Links ]

29. Linnaeus, C. 1766. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum clases, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus differentiis, synonymis, locis. Vol. 1. Regnum animale. Twelfth edition, Laurentii Salvii, Holmiae, 824 pp. [ Links ]

30. Loponte, D. 2008. Arqueología del Humedal del Paraná Inferior (Bajíos Ribereños Meridionales). En A. Acosta & D. Loponte (comp.), Arqueología de la Cuenca del Plata (Série Monográfica). Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano, Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

31. Loponte, D. & A. Acosta. 2003-2005. Nuevas perspectivas para la arqueología "guaraní" en el humedal del Paraná inferior y Río de la Plata. Cuadernos del Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano 20: 179-197. [ Links ]

32. Loponte, D; A. Acosta, I. Caparelli & M. Pérez. 2011. La arqueología guaraní en el extremo meridional de la cuenca del Plata. In: D. Loponte & A. Acosta (eds.), Arqueología Tupíguaraní. Instituto Nacional de Antropología y pensamiento Latinoamericano, Buenos Aires, p. 111-154. [ Links ]

33. Loponte, D, A. Acosta & L. Mucciolo. 2012. Avances en el conocimiento del registro precerámico en el Delta del Paraná: el sitio Isla Lechiguanas 1. Comechingonia. Revista de Arqueología 16: 229-268. [ Links ]

34. Marshall, L.G., A. Berta, R. Hoffstetter, R. Pascual, O. Reig , M. Bombin & A. Mones. 1984. Mammals and stratigraphy: geochronology of the continental mammal-bearing quaternary of South America. Paleovertebrata, Memoire Extraordinaire, 1984: 1-76. [ Links ]

35. Musali, J. 2010. El rol de los peces en la dieta de los grupos horticultores de tradición tupíguaraní: el caso de Arroyo Fredes (Partido de San Fernando, provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina). Archaeofauna, International Journal of archaeozoology, 19: 37-58. [ Links ]

36. Pautasso, A.A. 2008. Mamíferos de la Provincia de Santa Fe, Argentina. Comunicaciones del Museo Provincial de Ciencias Naturales Florentino Ameghino 13 (2): 1-248. [ Links ]

37. Remorini, C. 2009. [Aporte a la Caracterización Etnográfica de los Procesos de Salud-Enfermedad en las Primeras Etapas del Ciclo Vital, en Comunidades Mbya-guarani de Misiones. República Argentina. PhD Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. [ Links ]]

38. Storr, G.C.C. 1780. Prodromus methodi mammalium. Literis Reissimis, Tubingae, 43 p. [ Links ]

39. Stutz, S., A.R. Prieto, & F.I. Isla. 2006. Holocene evolution of the Mar Chiquita coastal lagoon area (Argentina) indicated by pollen analysis. Journal of Quaternary Science 21: 17-28. [ Links ]

40. Tonello, M.S. & A.P. Prieto. 2010. Tendencias climáticas para los pastizales pampeanos durante el Pleistoceno tardío-Holoceno: estimaciones cuantitativas basadas en secuencias polínicas fósiles. Ameghiniana 47: 501-514. [ Links ]

41. Tonni, E.P., A.L. Cione & A.J. Figini. 1999. Predominance of arid climates indicated by mammals in the pampas of Argentina during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene. Paleogeography, Paleoclimatology, Paleoecology 147: 257-281. [ Links ]

42. Wilson, D.E. & R.A. Mittermeier. 2009: Handbook of the Mammals of the World, Volume 1: Carnivores. Barcelona, 885 p. [ Links ]

Recibido 11-II-2015

Aceptado: 10-VI-2015